What Do We Owe Indigenous America?

It is what it is. The United States of America is a massive, thriving global powerhouse that rivals the rest of the world in military, economic and political power. And we “Indians,” as we have come to be inaccurately but commonly known, are a part of it, whether we like it or not.

We’re probably a part of every American’s Thanksgiving story, too. If you’re from the old school, we Natives don’t exist in reality anymore, but we live on through your grandson Matthew, who is running around your gigantic house, making awful noises that he calls “war cries,” wearing a construction paper headdress he made in school, while you sit at the table waxing nostalgic about the good old days, when your greatest grandaddy arrived on a boat and the Indians and Pilgrims had a big friendly orgy over a bountiful harvest and so began America.

Or maybe you’re from the new school. You’re the guy at the hipster “friendsgiving” in Brooklyn who pulls up a video from some alternative media YouTube channel on your iPhone to remind all of your friends that a few dozen Wampanoag people were slaughtered in some 16th century massacre many Novembers ago, and after chugging your 10th craft beer, you even start to shed a few tears over it.

In any case, whether you like us or not, we’re a part of your story—a prop, or a side note. But here’s the thing: You probably don’t come close to realizing the degree to which indigenous people suffered and sacrificed so that America could be what it is today. Even if you’re well meaning, you’re probably not as grateful as you should be.

I have spent a lot of my free time in my adult life unlearning and then relearning American history. I had to, because my people are left out of it. I’m not unique. A lot of indigenous people go this route: spending our own precious time and money on supplemental education and resources so that we can explain to our children why and so many of us struggle. We have to go beyond the standard American public school route to explain away our trauma—to understand why, while Pilgrim descendants feast, most of our own don’t have access to the organic, non-GMO corn and squash that we invented but only you can afford to eat.

What we’ve learned (because we’ve often done the research ourselves), is that a lot has been stolen from Native people, a lot of harm has been inflicted upon Native people, and a lot of Americans remain very committed to sweeping this all under the rug. We’ve also learned that, unlike other Americans who have had crimes committed against them, Native people, historically and today, have had little success seeking reparations in court. The system was designed to block most attempts at getting back even a little bit of what we are owed.

But this isn’t about reparations, really. This is about acknowledgement. As a dual citizen of the United States and the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, I recognize that my own existence—a descendant of French fur traders, Lakota/Ojibwe people, and German immigrants—would not be possible without colonization, land grabs and globalization happening as it did.

I’m not mad: I like my life, I appreciate the freedoms and comforts and protections that come with being a woman in America (imperfect as it is), and most of all, I appreciate that my indigenous ancestors survived so that I can proudly say that I come from the strongest people who ever walked this continent.

I come from a people who still understand that we belong to the land and not the other way around. I’ve been raised by a people who understand the brutality, the genocide and the utter injustice of our history, and we would never wish that fate upon anybody else, because compassion is woven into our DNA more tightly than conquest is woven into yours.

So today, on Thanksgiving, I won’t make an argument for why we should get all of our land back, or why we should be owed a big chunk of money. But I will suggest that, at least for a moment, you take a break from your pumpkin pie and use your imagination to try your hardest to understand just how much Native people gave so that you could have your holiday, your property, your livelihood, your America.

Together, we’ll try to visualize and quantify the amount of debt that the United States has accrued over the years that is still owed, and will likely never be paid back, to indigenous people.

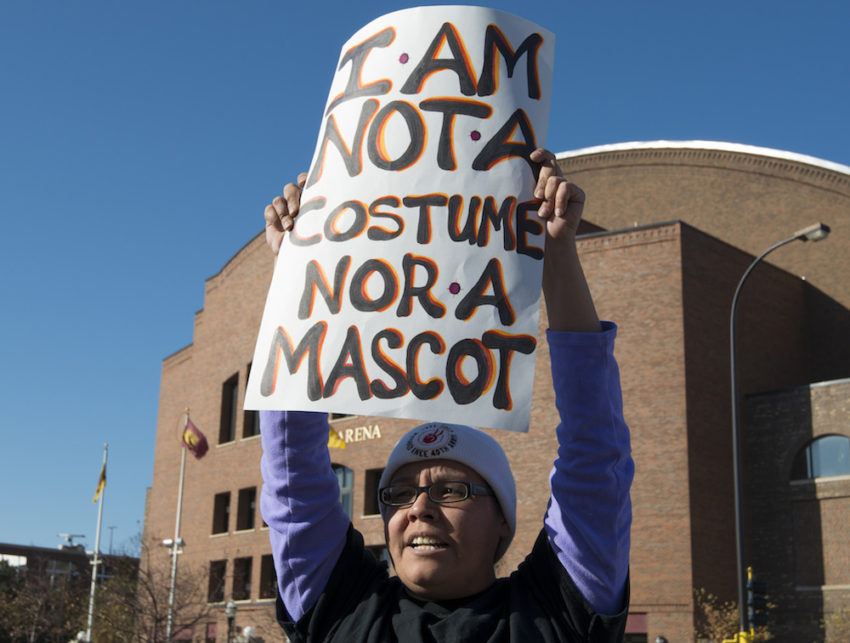

Ultimately, my wish is that every American boy and girl will understand and truly appreciate the sacrifices that indigenous people have made and continue to make for this country rather than continue to believe the sugarcoated version of American history that facilitates the prevailing notion that Native people are playthings, relics of the past, lazy savages who contributed nothing to American history. In fact, we were key players. We contributed everything. Just take a look at the numbers.

Loss of Lives: 100 Million

When you visualize early European arrival on the East Coast, you probably see a big empty forest. Then you zoom in and see a coastline with a few confused Natives scattered around, not doing much of anything except wondering about these white men. You zoom out again and see a big map of the U.S. without borders, and you imagine it mostly empty, save some small tribes of hunter-gatherers here and there.

In reality, low estimates show that the indigenous population of this continent in precolonial times numbered in the tens of millions. More recent estimates by historians show that there could have been hundreds of millions of people in the Americas. We know that there were massive cities, sprawling civilizations, agricultural empires and immense diversity in culture and art—comparable to any other continent: Europe, Africa or Asia.

Starting with a sweeping disease epidemic and culminating in 19th-century Indian wars, massacres and systematic cultural genocide, we know that countless millions of Native people were killed, often in brutal and painful ways, so that white people could take our property.

So now is the time to shift your thinking. My ancestors weren’t just a few scattered bands of merciless savages who deserved to die—we were, and are, human (just like you) who lost mothers, children, grandfathers and siblings in the most horrific ways imaginable. The degree of injustice wrapped up in that can never be truly quantified, but thinking about those numbers is a good start.

Loss of Land: 1.5 Billion Acres

Your fifth-grade social studies teacher probably didn’t show this to you, but this map tells the truth. “Between 1776 and 1887, the United States seized 1.5 billion acres of land from indigenous people.”

One thing that most tribes have in common is that land “ownership” was a foreign concept pre-America. That’s one reason why our leaders agreed to so many insanely unfair treaties—the concept of land loss was lost in translation. In any case, we once had freedom from coast to coast, and made our homes, hunted, fished and lived where we pleased. We demonstrated restraint and respect when it came to land development: We chose to keep the earth as pristine as possible (it wasn’t that we didn’t have the technology to destroy). But now, Indian trust land (reservations) make up only about 2 percent of the entire U.S. land base, and most of America is covered in structures that will crumble, corporate farms that produce cancer-causing food, and industries that continue to destroy the environment.

This wasn’t all so long ago, by the way. The post-World War II era saw continued U.S. theft of reservation territory. The Army Corps of Engineers flooded millions of acres of indigenous land on dozens of reservations during their heyday of dam building in the 1950s-60s so that the rest of America could benefit from electricity, while Native people who sacrificed our property were left with nothing.

Loss of Resources: Untold

There are a few ways of looking at this. In terms of dollars, imagine all of the natural resources that have ever been extracted, or ever will be extracted, from U.S. land (gold, coal, oil, lumber, you name it), add up that net worth (minus a fraction of a percentage that Native people have profited from), and realize that that’s all been stolen. The amount of wealth is unfathomable … definitely in the trillions of dollars. Meanwhile, Native people today suffer from some of the highest poverty and unemployment rates in the nation.

On some reservations, where natural resources are being utilized and extracted, thousand of indigenous people are stuck in the mix as unwilling accomplices to environmental degradation. Not all individual Native people agree on this, but there are those who would instantly stop oil extraction, mining, logging and other forms of destruction if they could. But as we saw in places like Standing Rock, we don’t always have a say in the matter—even when it’s on our own lands.

And then there’s the other way of looking at it: environmental justice. Indigenous nations have always been deeply committed and highly expert in conserving natural resources. The “take only what you need and use everything you take” mentality is an integral part of Native cultures, as is an air of utmost respect for the earth and everything that walks it.

But, by way of development and industry, the ecological devastation of American land has been massive, and the environment continues to suffer, while the health of Native people also suffers due to a lack of traditional food systems. In terms of what little is left of salmon, deer and other food staples, tribes have had to fight tooth and nail in federal court to maintain rights to hunt and fish on their own ancestral territory. It’s another piece of the pie that is often forgotten on Thanksgiving Day.

Loss of Livelihood: Immeasurable

I’m not a big fan of poverty porn or exploitation of the indigenous struggle. It’s an angle that has definitely been overdone by outsider journalists and documentarians who think they’re “helping” but in reality are painting a one-sided picture of our communities that dehumanizes us and minimizes our resilience. Anyway, contrary to the narrative, there are many Native people who have overcome all odds and are thriving, living happy and fulfilled lives, and enjoying the world just as much as anybody else.

However, while we are doing our best to emerge from it, the high rates of struggle do exist, and cannot be totally overlooked or denied. Here are a few hard facts to paint a picture:

● 1 in 4 Native people are in poverty today: the highest poverty rate for any ethnicity in the U.S.

● Some reservations’ unemployment rates are over 60 percent. The average is about 40 percent.

● The Native American suicide rate—particularly for teens—is the highest in the nation at more than twice the national average.

● Rates of PTSD among Native American youths are equal to that of combat veterans.

● Native people continue to die at higher rates and younger ages than the rest of Americans in a number of different categories, including heart disease, diabetes, accidental death, cirrhosis and more.

All told, there’s no doubt that the loss of land and resources, coupled with historical trauma from genocide and mixed in with cultural genocide from the boarding school era, have combined forces to create this tragic situation today. The loss of livelihood that we continue to experience as indigenous people will long be a burden that we have to bear so that others can enjoy the comforts of life in America.

Compensation: Practically Nil

On top of all the loss that we have experienced, Americans love to add salt to the wounds by talking about Native people as though we are living off “handouts”—a derogatory term that I have heard far too many times in my life.

Here’s the truth about these so-called “benefits” that so many people believe we receive.

1. We do pay taxes. Period.

2. We don’t go to college for free. Period. (If you want to argue with me on this one, I’d be happy to allow you to make a payment on my student loans).

3. Most of us don’t get casino money, per capita payments, or any other magical monthly check, and those who do have worked hard to fight for well-deserved settlements in court or to actually keep their casinos and other businesses running. The bottom line is that there are far more Native people in poverty than not.

4. Health care is the one thing that we do get for “free”—because it was promised to us through a series of agreements with the federal government. However, our Indian Health Service is chronically underfunded, and it’s basically the crappiest health care you can imagine (though it’s getting better as more Native doctors and nurses are taking over).

5. Anybody who expresses other sentiments about us being lazy or living off the government should probably refer back to the examples I gave of white theft and remember that they would have nothing without our sacrifices.

The Point

The point here, as I mentioned, is not to conjure up white guilt or to ask for reparations. It’s to remind Americans, on Thanksgiving Day, that it’s important to learn from our own history—our true history—so that we don’t repeat it. If by now you feel motivated to continue celebrating the holiday with a suddenly woke perspective and a burst of gratitude for indigenous brothers and sisters, here are a few talking points that should occupy the rest of your time at the dinner table:

1. Why is it that Hollywood produces so few films about Native American history from the Native perspective, but we see about 10 films per year that touch on American heroism or World War II?

2. How many pages in my high school history textbook were actually dedicated to pre-1492 history?

3. Why do we keep saying “Indian” when we know that there are over 567 tribes in the U.S. alone, and none of them historically have called themselves “Indians”?

4. How can I contribute to indigenous social justice movements beyond reposting things on social media?

5. How can I prepare myself to defend Native people next time I hear a racist comment about them?

6. Finally: What can Native people teach me? Too often, we forget that there is plenty to be learned from groups whose voices have been silenced and whose perspectives have been marginalized.

Let’s change that.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten