Who Killed Mary Pinchot Meyer?

JFK had a thing for blondes. Everyone knows about his affair with Marilyn Monroe; yet not as many know about Mary Pinchot Meyer, another beautiful, curvy blonde who gave JFK pause.

Like Monroe, Meyer too died young, murdered on a towpath in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. in broad daylight on October 12m 1964. More than 50 years later, her murder remains unsolved — but the holes in the story, her close CIA ties, and her affair with JFK have led many to believe that Meyer’s life ended with a professional hit. A curiously involved, ornate, and clumsy hit — but a hit nonetheless.

Who was Mary Pinchot Meyer? What did she know? Why was she killed? And whose finger pulled the trigger — if there was really a gun involved at all?

Who Was Mary Pinchot Meyer?

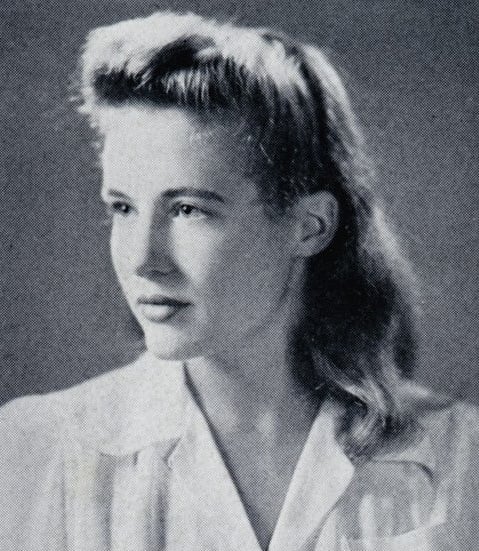

Vassar CollegeMary Pinchot Meyer.

Most women in 1960s Georgetown were more Jackie than Marilyn: white-gloved, tea-drinking, Pall Mall-smoking housewives whose Mad Men era coifs could always be seen at a PTA meeting.

Mary Pinchot Meyer existed outside of those appearances and expectations. An artist, she regularly carried a pouch of pot and acid with her, never ceasing to inspire fascination among the Georgetown elite.

Nevertheless, she’d married Cord Meyer — a CIA operative — in 1945. The two of them had three boys together and lived in Washington, D.C. where Cord, like many CIA agents, had a series of covers and aliases provided to him by places like Georgetown University and other safe houses. At home, Meyer painted and raised their boys.

A few key faces made regular appearances at the Meyers’ home. First came Meyer’s sister, Antoinette (or Tony, as she was called), and their friend, Anne Truitt. Tony’s husband — former CIA affiliate, journalist, and eventual executive editor of The Washington Post Ben Bradlee — was also a fixture at the Meyers’ Georgetown home.

Given Cord’s involvement in the CIA, they also entertained fellow agents, including a man named James Angleton, chief of CIA counterintelligence. All of these people come to play an important role in the solving — and in some ways maintaining — the mystery of Mary Pinchot Meyer’s demise.

But before her own, it was another Meyer death that really charted the course of her family’s life – and the life of the man who would go on to write one of the only definitive accounts of Mary Pinchot Meyer’s life.

Just before Christmas 1956, the Meyers’ two eldest sons, Quenty and Michael, had departed from school-sanctioned holiday activities to go to a friend’s house to watch television — something that Meyer strictly prohibited in her house.

Afraid they would be late for dinner, the brothers ran home that evening, crossing a busy street in Georgetown. Quenty made the cross but Michael was hit by a car, killing him instantly. The death shook not just the Meyers, but a man named Peter Janney, Michael’s best friend. Janney, who knew the Meyers very well, would be one of the key players in unraveling the details following Meyer’s murder eight years later.

Michael’s death unhinged the Meyers’ marriage, and by the early 1960s, the couple had divorced. Meyer then had custody of her two remaining sons with whom she lived in a house owned by Bradlee. It was during these next few years that Mary Pinchot Meyer, through the friends she’d made in the CIA, would be introduced to President John F. Kennedy and his wife, Jackie.

Meyer And JFK

The story of JFK’s infidelities didn’t start with Mary Pinchot Meyer, but it may have ended with her — if only because he was assassinated in November of 1963, about a year before Meyer would be killed. Shortly before his assassination, JFK penned a letter to her imploring her to visit him.

“I know it is unwise, irrational, and that you may hate it,” he wrote, “— on the other hand you may not — and I will love it. You say that it is good for me not to get what I want. After all of these years — you should give me a more loving answer than that. Why don’t you just say yes.”

The letter (which fetched $89,000 at auction in 2016) never made it to Meyer. Though that may have been one missed connection, JFK entertained Mary Meyer on a semi-regular basis from early 1960 until his death in 1963, usually when his wife was away.

Some accounts imply that not only was her relationship with JFK a sexual one, but may have also been drug-motivated. Meyer was thought to have brought not just marijuana, but LSD, into the White House for their use.

But what really made Meyer dangerous to JFK was her mind: She was a liberally minded person with strong feelings about U.S. foreign policy, the threat of nuclear war, and the inherent dangers of the U.S. government.

Her beliefs were not necessarily unfounded, either. Having been married to a CIA agent and befriended many of the organization’s higher-ups, Meyer knew a lot — maybe too much. And if she was having informal, pot-laden conversations with the sitting president about such sensitive information, it wouldn’t have been all that shocking to hear that those in D.C.’s national security community deemed her a threat.

Given the sociopolitical climate in 1960s America, it wouldn’t have taken much for a woman like Meyer to earn that status — she didn’t conform to social standards, she didn’t blend in. In fact, she dropped acid and painted abstract art with infamous drug evangelist Timothy Leary.

And while it may seem unusual for a woman like that to be so close with the president himself, Mary Pinchot Meyer indeed was. That said, by the time JFK was assassinated on November 22, 1963, Mary had not been with him for quite some time.

Meyer’s sister noted that she did not seem as shocked or upset about JFK’s death as the rest of the country. Some believe that it was because she simply wasn’t surprised, or perhaps she had been privy to some kind of deadly threat against JFK from within the government — which would also explain why she had kept her distance from him for some time beforehand.

Of course, at this point in history, the general public didn’t even know about JFK’s affair with Meyer.

In fact, it would be another decade before the National Enquirer would imply that Meyer’s death, almost one year after JFK’s, had been part of a larger government conspiracy. But those close to her would come to be the first to suspect that Mary Pinchot Meyer’s death was more than just a random attack in a public park.

The Murder

On October 12, 1964, just two days shy of her 44th birthday, Mary Pinchot Meyer finished a painting at around noon. She pet the head of her cat, which had just given birth to yet another litter of kittens, their little mewls carrying up into the rafters of her studio as she worked.

She left the painting to dry and headed out for her daily, afternoon walk along the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal towpath. She walked down the street toward the the path entrance. A black car with tinted windows stopped her. When Meyer looked up, she smiled. The car held Polly Wisner, a friend departing for London with her husband, who would be stationed there as a CIA operative. Wisner was the last of Meyer’s friends to see her alive.

She continued down the road to the towpath, walking along the Potomac River. Opposite of where she strolled along the path, on the roadway on the other side of the canal, two mechanics — Henry Wiggins and William Branch — were getting ready to tow a stalled car that had been abandoned on the roadway. These men were the last to hear Meyer’s voice — as well as two gunshots.

“Someone help me!”

Wiggins later testified that he looked up after he heard the scream, the two gunshots, and saw a black man standing over the body of a white woman on the other side of the canal. He got into his tow truck to drive a mile or so up the road to the gas station where he worked. He called the police and reported the gun shots.

With a lot of holes in the story from there on out, we may never know for sure what happened next.

The first question, often mulled over by amateur online researchers, is the exact timing of the shooting and the police’s response. Wiggins’ call placed the shooting at between 12:23 p.m. and 12:25 p.m. But the prosecutor later testified that the police arrived at the scene as early as between 12.24 p.m. and 12:28 p.m. — meaning they may have had to have been notified of the shooting before it even occurred.

Also odd was the fact that no one called an ambulance. Wiggins, only seeing the scene from across the canal, could not have known for sure that the woman was dead — so why did only the homicide squad arrive on scene following police notification?

Another peculiarity came up in trial: The car on which Wiggins claimed he was working didn’t exist. The court requested a work ticket from the garage, and found none, nor did it find a record of who owned the car.

It also seemed strange that, only Wiggins, Branch, and a man who worked for the government — Lt. William Mitchell, who had passed Meyer as he jogged through the park just before she was shot — had any idea of what had transpired.

And the story gets even weirder from there: Mitchell, it would come to pass, was just one alias used by a man who worked for the CIA. A later investigation into his identity would reveal no record of a William Mitchell at Georgetown, making some wonder just who he was — and why he was jogging past Meyer moments before she was killed.

In Janney’s book, he claims that Mitchell confessed to a reporter (who then told his attorney, who then told Janney) that he had been given an order to surveil Meyer due to her reaction to the Warren Commission’s report, which detailed the assassination of JFK and had been released just two weeks earlier. That order then escalated from surveillance to the order of “taking her out.” This forms a pretty compelling narrative, but as it is hearsay, none of it has ever been substantiated.

There was, of course, one other key player: Ray Crump Jr., the black man who was seen standing above Meyer’s body by Wiggins. Crump had a violent past, a criminal history, and was still in the park when the police arrived. Police arrested Crump on site within the hour after Meyer’s death and charged him with her murder.

Crump’s motive was unclear and the police found no weapon, but the official story said that he was either attempting to rob or rape her, perhaps both, and she had fought him off. He then shot her twice — once in the head, and once in the back, which punctured her aorta — at point-blank range.

Also odd was the composition of Meyer’s dead body. The coroner’s report implied that her wounds would have bled profusely, but the very first person to arrive at the scene, who saw her dead body in the grass ten minutes before police arrived, reported that her wounds looked almost bloodless.

A young reporter named Lance Marrow had heard the call for the police on the scanner, and had raced from his office to the park. Marrow was with Meyer’s body for about ten minutes before the police arrived, armed with nothing but his reporter’s notebook. He later wrote about it for Smithsonian Magazine:

I approached the body of Mary Pinchot Meyer and stood over it, weirdly and awkwardly alone as the police advanced from either direction.She lay on her side, as if sleeping. She was dressed in a light blue fluffy angora sweater, pedal pushers and sneakers. She was an artist and had a studio nearby, and she had gone out for her usual lunchtime walk. I saw a neat and almost bloodless bullet hole in her head. She looked entirely peaceful, vaguely patrician. She had an air of Georgetown. I stood there with her until the police came up. I held a reporter’s notebook. The cops from the homicide squad knew me. They told me to move away.

Stranger still is the fact that there are very few photos of the crime scene — odd because of course more reporters than Marrow showed up in response to the report of a gorgeous, Georgetown socialite shot dead in broad daylight. The photos that do exist are bizarre, and look a bit staged.

The picture that immortalized the case shows many people surrounding Mary Pinchot Meyer’s crumpled body on the ground. Police, medical examiners — men in suits. Who were they? Why hadn’t the police limited the number of people in the area? Why hadn’t they secured it, so that they could collect trace evidence that could prove who killed her?

Arthur Ellis, The Associated Press reporter who took the photo, remarked, “The police kept us on the other side of the canal for a long time. I took the picture with a long-angle lens, and when I look at it now I wonder who all those men in the picture were.”

The Mystery

Let’s Roll Forums

Ray Crump Jr. was the only suspect, and many who believe that the government may have taken Mary Pinchot Meyer out suggest that he was the perfect patsy. Crump had a violent criminal record. He was simply a black man in a country rife with racial tension. This was 1964 — racial segregation had only been officially abolished by the Civil Rights Act less than six months before.

Crump was acquitted, however, in large part because the only evidence against him was circumstantial — and because investigators never recovered a gun, and had nothing to link him to a weapon. Still, others say Crump’s acquittal had to do with the jury’s racial makeup. Another of Meyer’s biographers, Nina Burleigh, points out that the jury who acquitted Crump consisted of all black jurors. Had the jury been majority white, Crump may not have fared as well.

Police never identified another suspect. Meyer’s case was officially closed, unsolved. But many journalists, writers and internet sleuths have devoted hours, if not years, to figuring out what happened to her.

On the Let’s Roll forum, pages upon pages of forum conversation are devoted to nitpicking photos and looking at Google Maps shots of the park as it is today to assess if it’s physically possible for Higgins to have actually seen what he claimed.

Others ask that if Meyer’s death was part of some government-silencing conspiracy, why would the CIA put a hit on her in such a risky, public place? Why not just kill her at home and make it look like a robbery? Why create such a bizarre crime scene, why involve such specific and convenient witnesses?

The one piece of evidence that may have answered these questions was her diary, where she would likely have written about her fears, her relationship with JFK, and her relations to the CIA. But that diary was confiscated by James Angleton, Meyer’s friend and head of CIA counterintelligence, via her sister Tony right after Meyer’s death.

He destroyed it at CIA headquarters.

In 1976, The National Enquirer began running pieces about Meyer’s affair with JFK, which lit a fire under conspiracy theorists, one that still burns bright today.

Their theories are endless and dizzying, sometimes compelling and always provocative. Ben Bradlee, Meyer’s brother-in-law, confirmed her relationship with JFK in his memoir published in the mid-1990s, even though it directly contradicted what he had testified in court decades before.

Perhaps all we truly know about Mary Pinchot Meyer is that she was, for a time, involved with John F. Kennedy, while he was president. She had strong ties to the CIA and plenty of concerns about the U.S. government. She was murdered in the middle of a fall day, on a towpath in Georgetown. And the only personal effect she had with her was a tube of lipstick: Cherries in the Snow. A vibrant shade of bright red, the color of fresh blood.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten