By 2008, I had retired from the Times and was covering the caucuses for Truthdig. No longer part of the mainstream journalism pack, I viewed the caucuses as an outsider, which permitted me to see the events for what they were.

“The caucuses are a travesty of the American political system,” I wrote in a 2007 column several days before the election. “They are … undemocratic, unfair, unrepresentative and overly complicated.” A few days later, with the caucuses fast approaching, I urged the media “to try to shed light on the process instead of helping Iowa keep this promotional device alive. Unmask the wizard, journalists, and set America free from the shackles of the Iowa caucuses.”

Of course, no one listened. The lure of the state’s rural geography, small towns, and eager-to-please Iowans was irresistible to the press corps. So was the possibility of good assignments and promotions that often followed completion of an Iowa assignment the bosses liked.

So the media followed its usual pattern, trailing candidates from school auditoriums to coffee shops, interviewing prospective voters (whose answers seemed increasingly canned) and following the polls as if they were the Daily Racing Form.

Apparently, only a few of the most tech-minded paid attention to the most boring — and most important part — of an election, how the votes were counted.

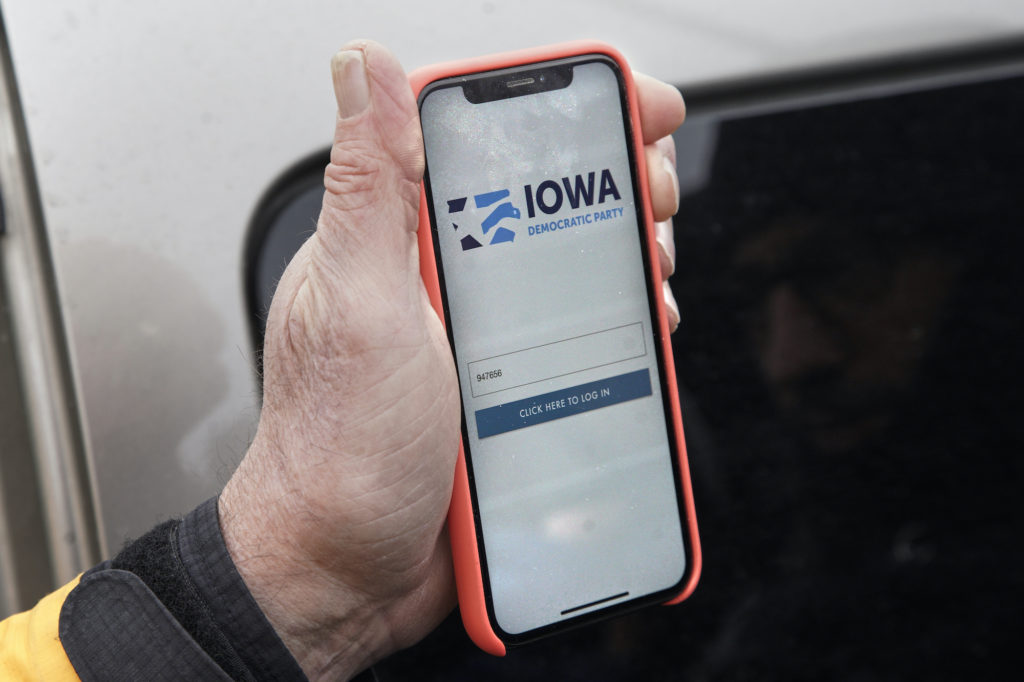

Even more complications were added this year to the incomprehensible process I chronicled in 2008. A barely tested app was handed out to caucus chairs, purportedly to speed reporting of each caucus result. It proved difficult to download for the incompletely trained volunteers who run the caucuses. The app’s reporting capabilities were problematical. Days passed with no final results.

This has thrown the press into unknown territory. The scenario of a winner being crowned in Iowa, then heading into New Hampshire and other contests, has been shattered. Utter media confusion reigned Monday night through Wednesday.

More important than the inconvenience Iowa caused the press, however, is what the state means to public perception of the many U.S. primary elections, not to mention the big one in November, when the nation selects a president.

I live and vote in the most populous county in the nation, Los Angeles, which has more than 10 million residents. The county has long been afflicted with slow vote counts due to its size and to snafus by the vote tallying equipment installed by one of the few companies that do such work.

For this election, the county has created its own system, with voters given two options: voting by mail or going to a polling place and marking computer screens or hand-marking paper ballots. And, instead of using familiar local polling places, people who vote in person must travel to centralized voting centers.

The Los Angeles registrar-recorder, Dean Logan, and his staff have been working hard to make the new system work. But Libby Denkmann, who has been tracking the system, reported on LAist that “the county must meet a stack of requirements before primary election voters get their hands on the machines Feb. 22.”

I have watched enough elections and used computers long enough to know that, more likely than not, something will go wrong. The same is true for the other primary elections coming up around the country.

So let’s drive a stake into the heart of the Iowa caucuses. Let them die.

But reporters and their editors should not forget the real lesson of Iowa. The story of the 2020 election may end up being found in the back offices of voting officials and among the techies who create their voting systems. Reporting on them is tedious and complex. But it is the kind of journalism that is more important and necessary than chasing candidates around Iowa.

Democracy is at stake. More elections such as the one in Iowa will further erode the faith many Americans have in democratic institutions. If nobody believes election results, democracy, which is under assault every day, will wither and die.