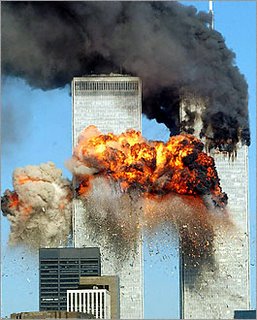

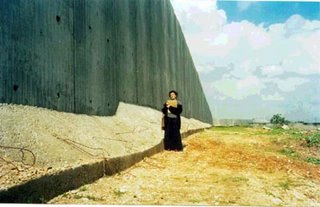

De Amerikaanse journalist Greg Mitchell schrijft: 'The War Reporter Who Turned Prophet on Iraq. Looking back at E&P's extensive commentary on media coverage of the Iraq war three years ago, I was struck again by how Chris Hedges stands out as a kind of seer. The longtime war reporter, who decided to sit this one out, was among the few who recognized that taking Baghdad would be the easy part. By Greg Mitchell (March 28, 2006) -- Looking back at E&P’s extensive, and often critical, commentary on media coverage of the Iraq war three years ago, I was struck again by how Chris Hedges stands out as a kind of prophet. The longtime war reporter, who decided to sit this one out, was among the few who recognized that taking Baghdad would be the easy part. Let's contrast it with the criminal incompetence of the U.S. war planners. That British memo recording President Bush's meeting with Prime Minister Blair two months before the war, in contrast, reveals that the two leaders expected an easy ride during the occupation with little sectarian violence. One thing Hedges said back then, in early April 2003, has stuck with me. I think it could go down, unfortunately, as the most prescient quote of the entire war. Speaking of what the U.S. was facing in an Iraq occupation, he said: “It reminds me of what happened to the Israelis after taking over Gaza, moving among hostile populations. It's 1967, and we've just become Israel.”E&P contributor Barbara Bedway interviewed Hedges during the run-up to the war in early 2003, and then during and just after the invasion. He was a logical source. Hedges had covered 12 wars, most recently for The New York Times, and was held for a week by the Iraqi Republican Guard during the Shiite uprising following the Gulf War. He also wrote the influential book, "War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning."Even before the attack on Iraq, he warned of the limits of the embedding program, which discouraged independent reporting on the “other side,” the civilian toll, and the long-term obstacles to the success of any occupation. "Most reporters in war are part of the problem," he cautioned. "You always go out and look for that narrative, like the hometown hero, to give the war a kind of coherency that it doesn't have. “He also warned: “When the military has a war to win, everything gets sacrificed before that objective, including the truth." About a month into the occupation, in May 2003, he said: "We didn't ever discover how many civilian casualties occurred in the first Gulf War, and I doubt we'll ever know about this one." And: "We don't have a sense of what we have waded into here. The deep divisions among the varying factions could be extremely hard to bridge, and the historical and cultural roots are probably beyond the American understanding…. For occupation troops, everyone becomes the enemy."In his book, Hedges was prone to impassioned meditations on how the seductive attractions of war obscure its harsher truths, and that, even when necessary, it is a sickening, not a glorious, enterprise. He has said that he wrote the book because he feared that "we are losing touch with ourselves, with our role in the world, and with the danger such enthusiasm for war ultimately brings to our nation. … I wanted to lay bare war's contagion. And I wanted to do it now as we enter a new and volatile moment in our history, one where introspection is so necessary and so lacking."Bedway’s article from April 2, 2003, deserves another look. I’m not sure whether I should say “read it and weep” or “read it and learn.” It may be too late for the latter. Here are some excerpts from the article.*For Chris Hedges, the veteran journalist who has covered over a dozen conflicts around the globe, it's clear that the U.S. military's use of embedded reporters in Iraq has made the war easier to see and harder to understand. Yes, "print is doing a better job than TV," he observes. "The broadcast media display all these retired generals and charts and graphs, it looks like a giant game of Risk [the board game]. I find it nauseating." But even the print embeds have little choice but to "look at Iraq totally through the eyes of the U.S. military," he points out. "That's a very distorted and self-serving view." To Hedges, who is fluent in Arabic, this instantaneous "slice of war" reporting is bereft of context. Reporters have a difficult time interviewing Iraqi civilians, and many don't even try, he says: "We don't know what the Iraqis think." The reporters are "talking about a country and culture they know nothing about."Hedges believes the growing hostility between the Iraqis and Americans makes covering the war a far more dangerous job than reporters could have initially imagined: "My suspicion is that the Iraqis view it as an invasion and occupation, not a liberation. This resistance we are seeing may in fact just be the beginning of organized resistance, not the death throes of Saddam's fedayeen. I've witnessed how insurgencies build in other conflicts -- guerilla leaders [could appear] who are unknown to us now. They know the landscape. “It reminds me of what happened to the Israelis after taking over Gaza, moving among hostile populations. It's 1967, and we've just become Israel. I fear what happened there will happen here."The real "shock and awe" may be that we've been lulled into a belief that we can wage war cost-free, according to Hedges: "We feel we can fight wars and others will die and we won't. We lose track of what war is and what it can do to a society. The military had a great disquiet about the war plans, as far back as last fall. The press did not chase down that story."The best preparation for covering war does not lie in one-week boot camp training for journalists, Hedges says ruefully, but having a deep understanding of the humanities: "In seminary, we put so much time into studying human nature, how moral choices are made. I have a deep respect for Islam that I learned in seminary -- I don't look at Arabs as two-dimensional figures. I'm a great believer in the humanities. If you know Shakespeare, you know human nature."