“BORING.” That was Donald Trump’s instant verdict on the New York Times’s blockbuster

investigation into the rampant tax fraud and nepotism that undergirds his fortune. Sarah Huckabee Sanders heartily concurred, informing the White House press corps that she refused to “go through every line of a very boring, 14,000-word story.”

Welcome to a new political PR strategy premised on the shredding of the American mind — you don’t want to even try to read that interminable article; check out my Twitter feed instead, and this viral video of me saying rabid things.

The Times investigation, published as a standalone supplement on Sunday, is about as boring as a car accident. It shows in lavish detail that Trump’s creation myth is and always has been a work of fiction. No, he did not take a “very, very small” million-dollar loan from his father and use his deal-making acumen to parlay it into a $10-billion global empire, while paying the original loan back with interest.

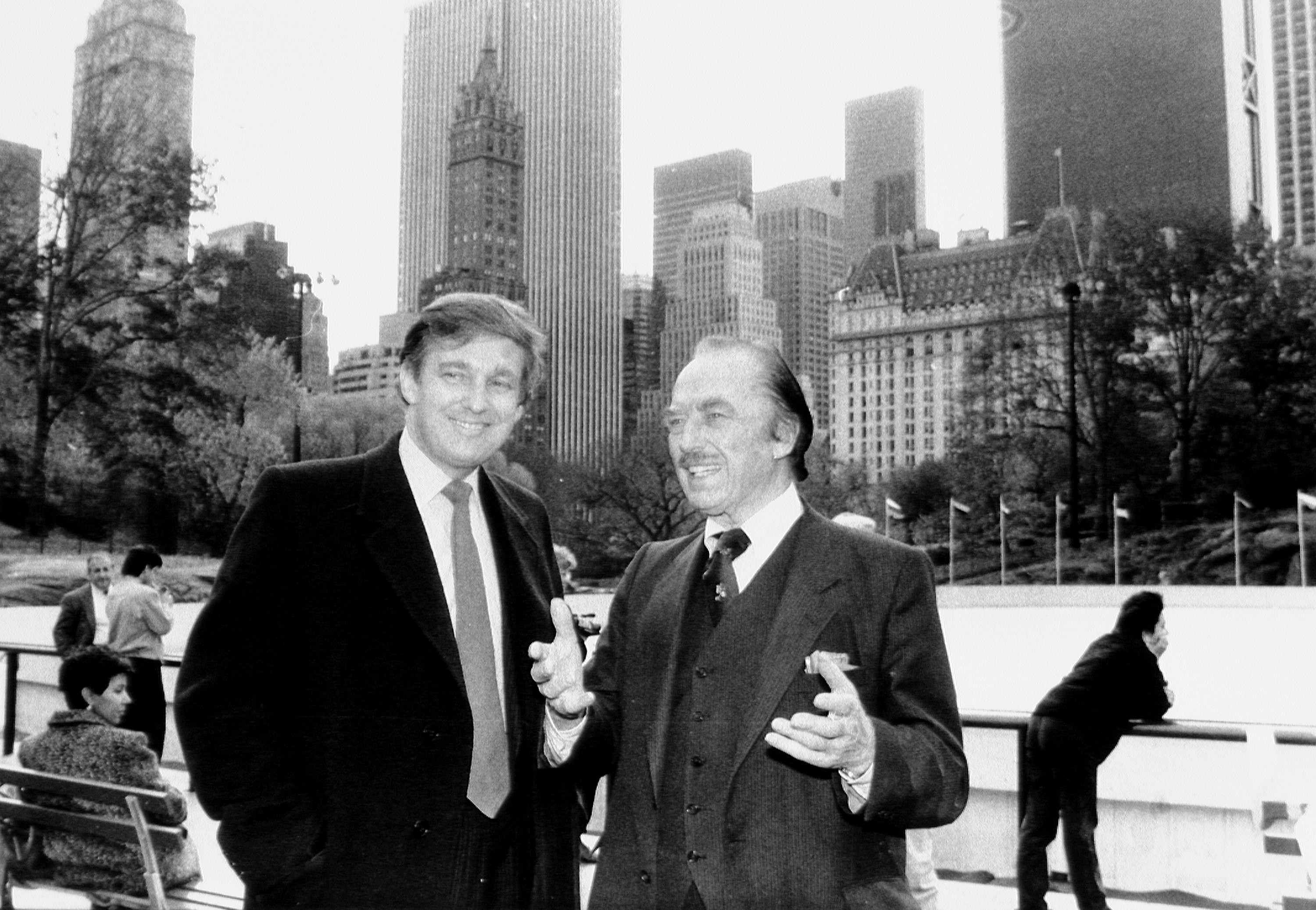

Donald Trump and Fred Trump attend “The Art of the Deal” book party on Dec. 12, 1987 at Trump Tower in New York City.

Photo: Ron Galella/WireImage/Getty Images

Trump has been sucking on a spigot of his father’s cash nonstop since he was in diapers, becoming a millionaire by middle school. According to the Times, when all was said and done, “Mr. Trump received the equivalent today of at least $413 million from his father’s real estate empire, starting when he was a toddler and continuing to this day.” Moreover, “much of it was never repaid.” As for the rest of the mythology, not only was he spending his father’s money, he blew much of it on disastrous deal after disastrous deal. Only to be bailed out by his father’s millions time and time again.

Rather than bothering to deny any of this, Trump and his surrogates have simply spun a new creation myth. No longer the scrappy, self-made man, Trump is being reincarnated in real time as the chosen son, with he and his father acting as partners in wealth creation. “One thing the article did get right,” Sanders said, clearly reading from notes, “is it showed that the president’s father actually had a great deal of confidence in him. In fact, the president brought his father into a lot of deals and made a lot of money together. So much so that his father went on to say that ‘everything [Trump] touched turned to gold.’”

This shift is more significant than it first appears. After a couple of years of hobnobbing with Saudi monarchs and Queen Elizabeth II, the president appears ready to embrace his true identity as a scion of a dynasty who did not build his fortune by himself, but who is, instead, the product of an especially blessed family that passes a magic touch through the generations.

What makes the Times’ revelations more important is that they are a rare window into an even larger story about the growing political and economic role of inherited money in the United States — the culmination of decades in which a handful of sons and daughters of bequeathed wealth waged a fierce and relentless battle of ideas against the very concept of equality and majority rule, all based on the same corrupting belief in their own inherent superiority.

Trump may be the highest profile of such heirs to wield political power, but he never would have gotten where he is without the ideological scaffolding carefully put in place by other scions of dynastic families — from the late John M. Olin and Richard Mellon Scaife in the ’80s and ’90s to Charles and David Koch and Rebekah Mercer today. These are the key figures who bankrolled the think tanks, financed the extreme free-market university programs, and funded the tea party shock troops that moved the Republican Party so far to the right that Trump could stomp in and grab it.

It was their project that created a fake consensus about the need for the radical deregulating of markets and dismantling of environmental protections, for lowering corporate taxes and eliminating the “

death tax” — and paying for it all by dismantling so-called entitlements. It was an effort that always required harnessing the emotional power of racism (think “welfare queens”), as well as the parallel construction of a highly racialized system of mass incarceration to warehouse the poor (and profit from them, of course). The Trump presidency — never mind the economic populism he bellowed on the election trail— is the near-perfect embodiment of this agenda.

A great deal of excellent investigative journalism has gone into tracking the money behind this sprawling class war, most notably by Jane Mayer in her indispensable “Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right.” Mayer

showed that though figures like the Kochs are highly ideological, the policies pushed by these wealthy families also happen to directly benefit their bottom lines. Laxer regulations, lower taxes, weaker unions, and unfettered access to international markets tend to do that.

Much less attention, however, has been paid to the implications of so much of this financing coming not just from unfathomably rich people, but people born that way. And yet it is striking that the figures at the dead center of this campaign were not Chicago school economists, nor were most of them self-made business leaders who had pulled themselves up by their bootstraps. They were, like Trump, pampered princelings whose fortunes had been handed to them by their parents.

The Koch brothers were raised in luxury and inherited Koch Industries from their father (who built his fortune constructing refineries under Stalin and Hitler). Scaife was an heir to the Gulf Oil, Alcoa Aluminum, and Mellon Banks fortunes and grew up in an estate so lavish it was populated with pet penguins. Olin took over his father’s weapons and chemicals company.

And so it goes, right down to Betsy DeVos, who was raised by billionaire Edgar Prince and married into the Amway fortune — and who has devoted her life to dismantling public education, now from inside the Trump administration. And let’s not forget Rupert Murdoch, who inherited a chain of newspapers from his father and is in the process of handing over his media empire to his sons. Or relative newcomer Rebekah Mercer, who has chipped off a chunk of her father Robert’s hedge fund fortune to bankroll Breitbart News, among other pet projects. In short, these people are Downton Abbey lords and masters, playacting as Ayn Rand heroes.

Of course, there are some self-made billionaires, like Sheldon Adelson, who have helped bankroll the revolution on the right. But when it comes to the battle of ideas — the careful investments in pro-business academic programs at elite universities, the extreme right-wing think tanks, the strident media outlets, and now the harnessing of big data and “machine learning” in Republican political campaigns — the role of inherited wealth cannot be overstated.

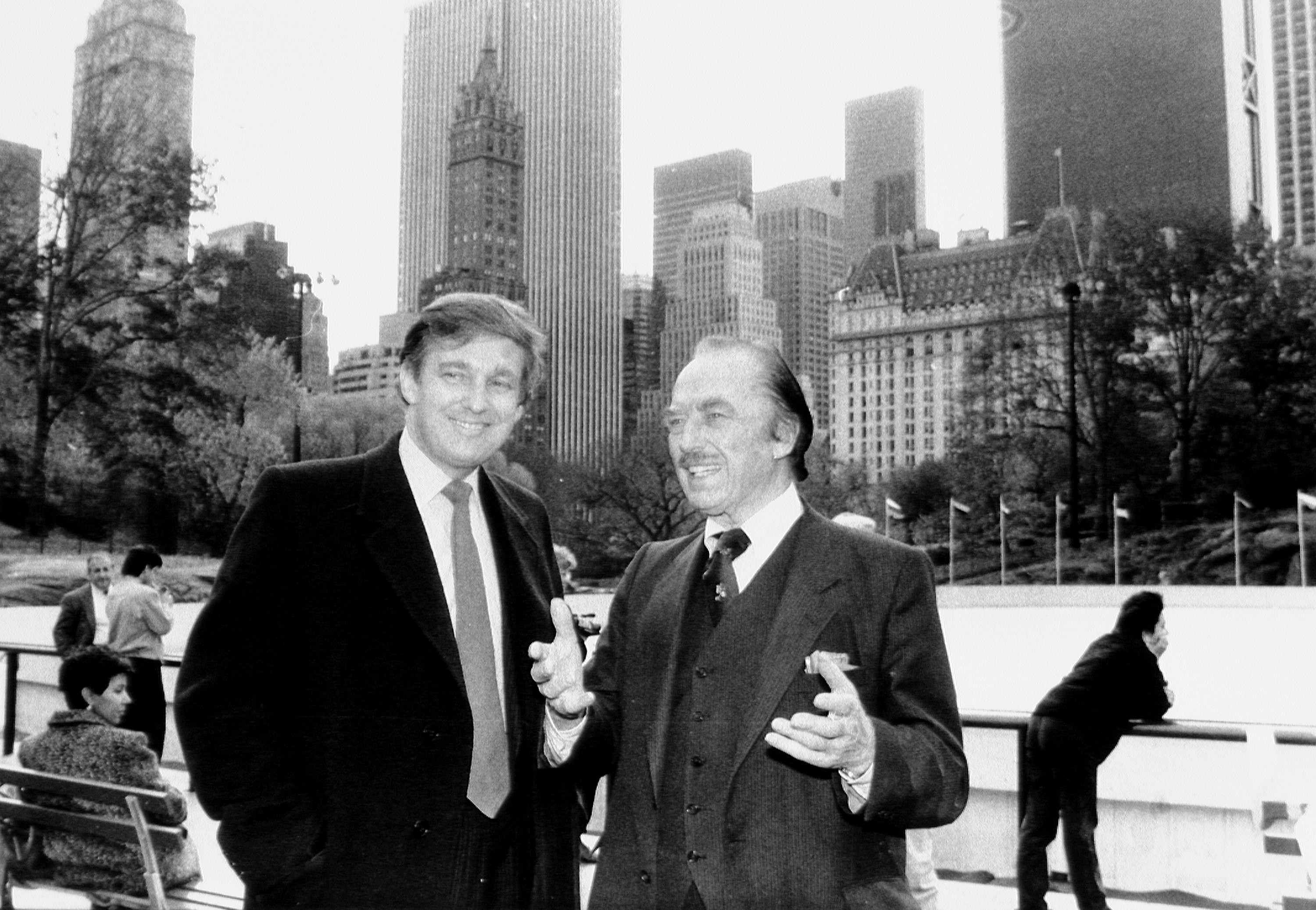

Donald Trump and his father, Fred Trump, at the opening of Wollman Rink in New York on Nov. 6, 1987.

Photo: Dennis Caruso/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

Self-Made Scions

It is worth pausing over this fact, because in a country with as powerful a meritocratic mythology as the United States, the heirs to great wealth often have a rather complicated relationship with their fortunes. Some blow it on yachts and vanity projects. Some become determined to show their fathers up by expanding their empires. Some give almost all of their wealth to charity. Some hide it from everyone they know. An all-too-rare few try to use their wealth to build a fairer economy and less toxic ecology.

But what must it take to pour large parts of a fortune that came to you by accident of birth into a relentless campaign of further affirmative action for the rich?

How exactly do you rationalize being lifted up by an intricate latticework of familial and social supports (tutors, prep schools, connections at the best universities, entry-level executive jobs, capital to play with), and then setting about shredding the meager safety net available to those without your good luck? How do you convince yourself that, despite having been handed so much, you are not just right but righteous in attacking the “handouts” received by single mothers working two jobs? How, when you know your own family fortune has benefited from enormous government subsidies (cheap housing loans for the Trumps, oil subsidies for the Kochs and Scaifes, direct weapons contracts for the Olins) do you begrudge paying the same tax rate as your employees?

What is the theory, the worldview, that makes all this OK? And how has it shaped the broader “free market” revolution paid for by these men — a crusade that has just achieved a new level of impunity with the ascent of Brett Kavanaugh, a product of this same world of unchecked privilege, to the Supreme Court?

You can claim to be a wealth-creator, sure. But because you didn’t actually create the wealth yourself — you inherited it — other rationales are required for why you deserve still more, while others should get far less. That’s where uglier ideas come in, about one’s inherent superiority, about a greater deservedness that apparently flows from being a member of a particularly good family, with better values, better breeding, a better religion, or as Trump so often claims, “

good genes.”

And of course the even darker side is the often unspoken conviction that the people who do not share in this kind of good fortune must possess the opposite traits — they must be defective in both body and mind. This is where the Republican Party’s increasingly savage racial and gender politics merge seamlessly with its radical wealth-stratifying economic project. Convinced that people belong where they are on the economic and social ladder, the party can keep redistributing wealth upward to the dynastic families that fund their movement, while kicking the ladder out of the way for those reaching for the lower rungs.

In this context, the “losers” (Trump’s favorite insult, aimed disproportionately at the nonwhite and non-male), can not only be stripped of food stamps and health care and left for more than a year without roofs in Puerto Rico, but are also acceptable targets for all kinds of degradations, whether having their children caged in desert internment

camps, or having their experiences of sexual assault mocked in open arenas.

The latter part of this equation is what Trump is offering to his base: Their birth will never reward them with anything like the hundreds of millions showered on the Trumps. But they are being invited to share in their own, albeit more modest, birthright entitlements as white, middle-class Americans. They are being invited to be on the winning team, “taking our country back” from any and all invaders and threats, from immigrants taking “our” jobs to women bearing damaging stories against “our” sons.

That is the grand bargain: Trump gets to fully claim his inheritance as a scion of wealth and his base gets to claim their inheritance as white citizens of a Christian, patriarchal nation. Oh, and like the royal families with whom he is so enamored, Trump will reward his loyal subjects by putting on an endless stream of entertaining shows and performances. He hasn’t gotten his military parade yet, but think of Trump’s ritualistic rallies and never-off reality show as crasser versions of royal pomp and palace intrigues. The divine right of kings has been replaced by the divine right of wealth — and it looks almost exactly the same.

None of this should be surprising. Any system marked by sharp inequality and injustice requires a narrative of justification. Colonial savagery and land theft required the doctrine of discovery, manifest destiny, terra nullius, and other expressions of Christian and European supremacy. The transatlantic slave trade, similarly, demanded an intellectual and legal system built on white supremacy and “scientific” racism. Patriarchy and the subjugation of women required an architecture of yet more pseudoscientific theories about female intellectual inferiority and emotionality.

Without these theories — and the lawyers, scientists, and other experts who stepped forward to give them credence — the injustices of all these systems would have been untenable. Our current system of ever more grotesque inequalities is no different. The mythology of the self-made elite once did the trick of justifying the United States’ wealth gap and threadbare safety net.

The ultrarich in the United States have long insisted that they built their empires with sweat and smarts, unlike their aristocratic brethren in Britain and France, and therefore deserve them more. Central to this story was the idea that anyone with smarts and drive could do the same, since there was no entrenched class system stopping them. (In the Trumpian version of this story, you could be just like him if you paid up for his how-to-get-rich books and fraudulent “university” while studying back episodes of “The Apprentice”).

“We like to pretend that no such thing as a ruling class has ever darkened an American shore or danced by the light of an American moon,” former Harper’s editor Lewis Lapham once

remarked.

This was never true. The American political system began as a protection racket for propertied white men, granting inalienable rights to a minority at the direct expense of enslaved Africans and women. Serious proposals to level the playing field — from a truly integrated public school system to fair wages for domestic work — were squashed again and again.

Meanwhile, like Trump himself, many of the hypersuccessful men who proudly wear the mantle of being “self-made” are in profound denial about how much help they received from their family and social networks. Kavanaugh, a member of the American elite, if not the ultrarich, is a case in point. During the Senate hearings, he snarled that he got into Yale Law School by “busting my tail,” insisting “I had no connections there.” No connections except that his grandfather went to Yale, which means that Kavanaugh very likely didn’t get in only because he managed to do his homework with a piercing hangover, but also because he was a prime candidate for a “legacy” admittance.

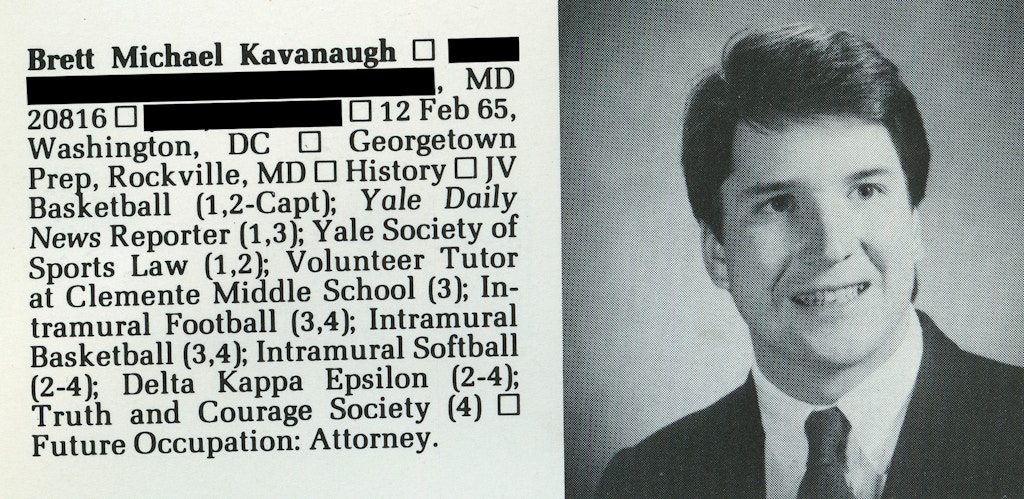

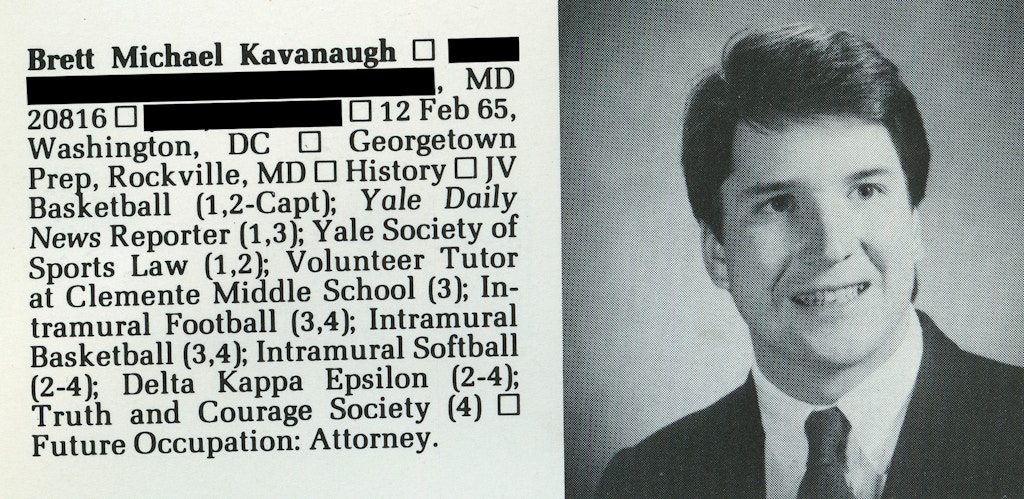

An excerpt from Brett Kavanaugh’s Yale yearbook. Some personal information has been redacted for privacy.

Image: White House released

The truth is that many children of elite families enjoy all kinds of unacknowledged protections that make failure a herculean effort. In childhood, bad grades are fixed with expensive tutoring (and, if necessarily, remedial boarding or military schools.) At top Ivy League universities, rampant

grade inflation is a poorly kept secret, with wealthy students frequently lodging successful grievances against professors and graduate students who dare give them anything less than an “A,” no matter how mediocre their work. In adulthood, bad business bets are backstopped with family money and connections. On Wall Street, it’s the government that steps in to bail out reckless bets since chances are that your workplace is too big to fail.

None of this is to say that the very wealthy are lazy or lead lives free of pain. Many work nonstop (as do the working poor, under unimaginably harder conditions). Moreover, elite institutions — prep schools, fraternities, secret societies — tend to build in their own brutal hazing rituals. Top corporate law firms and investment banks put new recruits through grueling hours and ruthlessly pit them against one another for bonuses and promotions.

Inside families with great fortunes at stake, siblings are similarly pitted against each other for control of the greatest prizes. So Trump fashioned himself as a “killer” to beat out his older brother Fred for his father’s favor. And, as Mayer reported, the three younger Koch brothers staged a mock trial accusing their oldest brother (also named Fred) of being gay so that he would relinquish his claim to the family fortune.

All of this is part of a time-tested process of training and indoctrination designed to toughen up the soft sons of privilege so they are ready to be as cutthroat as their fathers. But surviving such elite trials often convinces people like Donald Trump, Charles Koch, and Brett Kavanaugh that they are where they are solely because they worked their respective tails off.

Citadel Investment Group President and CEO Kenneth Griffin testifies on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 13, 2008, before the House Oversight and Government Reform hearing on “Hedge Funds and the Financial Market.”

Photo: Kevin Wolf/AP

Failure Is for Other People

It reminds me of a talk I once heard by Kenneth Griffin, a billionaire hedge fund manager in Chicago, who at the time was in a state of distress about an Obama plan to increase taxes. Speaking to a group of elite college students about his rise to enormous wealth, he told a story about how his family had given him some capital to start a hedge fund in his Harvard dorm room (where so many rags-to-riches stories seem to begin), complete with a satellite hook-up to receive real-time market data. He confessed to the students that this first foray into trading had not gone well, that he had in fact lost a lot of other people’s money. Fortunately, however, he was entrusted with still more start-up capital, was able to start again, and that’s where he began his rise to being what he is today: the richest man in Illinois.

Asked by a student how he got through the tough times, this “self-made” billionaire replied: “America is incredibly forgiving of failure.”

What struck me most at the time was that Griffin seemed to genuinely believe what he was saying — that a country in which millions are one illness away from homelessness, and which at that time imprisoned 2.3 million people, “is incredibly forgiving of failure.” He was convinced that his personal experience of being repeatedly caught by his own personal family safety net was a universal American experience — and that let him fight to lower his tax bill and further shred the safety net with what appeared to be a clear conscience.

Chuck Collins, an heir to a family fortune who gave it up in order to

fightentrenched inequality, recently wrote about the moral risks that accrue when so many powerful people, from Trump to Kavanaugh, deceive themselves about how much they were helped. “If I believe that success is based entirely on personal grit,” he wrote for

CNN, “then why should I pay taxes so that someone else can have a comparable head start to mine — with early childhood education, access to quality health care and mental health services, and low-cost higher education?”

Why indeed? And why support any form of affirmative action when you are in denial about all the extra support that landed you where you are today?

There are other moral hazards that result from this denial as well — perils that put whole societies at risk when these overconfident men assume power. Because if your experience is that every time you stumble, you recover as if by magic, then you will be much more prone to upping the ante next time, convinced that you and yours will surely be alright in the end, as you have always been.

So why not refuse to

regulate derivatives? The market will self-correct. Why not pour that toxic waste into a river? The solution to pollution is dilution, right? And why not invade Iraq? It will surely be a “

cakewalk.” And while we’re at it, why not ignore decade after decade of warnings from climate scientists telling us that if we didn’t get emissions under control, we will run out of time? Come on, don’t be so negative, surely technology will save us, it certainly has been great for Uber.

I gave a TED

talk about this mentality a decade ago called “Addicted to Risk,” and if you want to know where it all leads, have a glance at the harrowing new U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

report, released earlier this week.

Because now the whole thing is unraveling. The reckless bets are coming due — economically and ecologically. And the self-made mythology is unraveling too. That’s why Trump isn’t bothering to defend himself — it’s all gotten too obvious to deny. Too much money is pooling at the highest economic echelons. Single families — like the Waltons and the Cargills — are hogging too many spots on the Forbes 400 list.

Back in 2012, United for a Fair Economy published a

report on the role of inherited wealth on that list. It found that “40 percent of the Forbes 400 list inherited a sizable asset from a family member or spouse, and over 20 percent inherited sufficient wealth to make the list. In addition, 17 percent of the Forbes 400 have family members on the list.”

There are signs that the role of inherited wealth has only increased since then. That’s because the assets held by the already rich — in real estate, the stock market, and in direct corporate profits — are growing at a significantly higher rate than the overall economy and the salaries of working people, which are stagnating.

This was one of the key insights of Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the Twenty-First Century”:

Whenever the rate of return on capital is significantly and durably higher than the growth rate of the economy, it is all but inevitable that inheritance (of fortunes accumulated in the past) predominates over saving (wealth accumulated in the present). … Wealth originating in the past automatically grows more rapidly, even without labour, than wealth stemming from work, which can be saved.

This is compounded by the successful crusade by the scions of the ultrarich to lower corporate and income taxes and chip away at the “death tax,” which once significantly shrunk the fortunes passed from one generation to the next. And then, as Collins points out, there is the complicity and creativity of tax lawyers and accounting firms who have grown ever more adept at hiding trillions in wealth from a scandalously complicit IRS. (Collins

calls it the “dynasty protection racket.”)

Under Trump, who has profited so handsomely from all of these rackets, the pots of wealth being passed down within families are set to overflow even further. Among the many handouts in Trump’s tax law, the first $22.4 million gifted from parents to children is exempt from the estate tax. (“Final Tax Bill Includes Huge Estate Tax Win for the Rich,” announced a euphoric Forbes

headline last December.)

Is it any surprise that, as the economy changes — with the very idea of meritocracy under sustained assault both by the new tech monopolies that quash competition and the increasing power of dynastic wealth — those uglier stories that rationalize untenable levels of inequality are roaring to the surface?

“60 Minutes” correspondent Lesley Stahl interviews President-elect Donald J. Trump and his family at his Manhattan home on Nov. 11, 2016.

Photo: CBS via Getty Images

Wealth and Destiny

These are the theories that hold that the wealthy and powerful deserve their lopsided share not primarily because of their hard work but because of their identity — the family they were born into, their (imagined) superior genetics, their supposedly elevated values, and of course, their race, religion, and gender. Inside the logic of this story, success does not come because you were showered with privileges. You were showered with privileges because you are better.

A few years back, Jamie Johnson, one of the heirs to the Johnson & Johnson fortune, interviewed other members of his wealthy cohort for the film “Born Rich” and its sequel, “The One Percent.” He observed that while he was struggling to understand why he deserved to be handed so much money just because he had managed to turn 21, “For some people I talked to, inequality is easy to understand. It’s preordained.”

People like Roy O. Martin III, president and CEO of the Louisiana-based Roy O. Martin Lumber Company, which was previously headed by his father and grandfather. Martin told Johnson, “If you inherit money, you feel ‘why did I get all this and somebody else is poor?’ Well, God has a reason for it. God’s never going to give you something you can’t handle.” Being rich, he went on, means that “God has given you a lot of assets to be stewards of.”

Collins told me that he has encountered these supremacist theories frequently in the moneyed circles he grew up in and in conversations around the estate tax — “and it’s happening more as we become more unequal.” In some cases, people are still genuinely convinced that they worked for all the money they have. But where this is obviously not the case, different justifications are emerging. “They responded that ‘our family is deserving. We have better values that we have passed on or a different work ethic.’” And sometimes, Collins told me, this self-justification slips into more dangerous territory. “You hear that this is all genetics. Or that ‘our health is better’ or ‘we have more energy.’”

Only ideas like these can help justify a passion to avoid taxes on a pile of wealth that has been passed through four generations. You have to believe there is something inherently superior about your family. And even if it is left unsaid, you also have to believe the corollary — that there is something inherently inferior about the people who would benefit from those taxes. Just as you deserve your unearned place at the top, so others must deserve theirs at the bottom — they are “bad hombres,” come from “shit-hole countries,” and so on. All the easier to abuse, deport, even torture.

Indeed, if you have been raised on a narrative of your own specialness and exceptionality, you may well be prone to believe that all kinds of things are your divine right. You might believe that you have a right to a lifetime appointment on the Supreme Court despite never having tried a case. You might believe you have a right to become president despite having a closet full of skeletons and no history of public service.

And, in some cases, you may well feel entitled to do things to people against their will who are not in your rarefied club — whether forcing a woman to carry a pregnancy she does not choose, or grabbing women’s bodies without their consent. Or to do whatever it takes to shut her up — be it a hand over her mouth or a “catch and kill” story in the National Inquirer.

Trump’s sense of entitlement to massive amounts of inherited wealth and political power is not something his mostly middle- and working-class followers have the privilege of sharing. But that misses an important point: In boiling times like ours, supremacist thinking is contagious. When elites indulge their ugliest beliefs about their divine right to keep winning, it trickles down, giving their supporters license to assume their own imagined superior status — over anyone who seems sufficiently undefended.

This is an intensely hierarchical worldview that is completely comfortable with a minority making decisions for a majority in a rigged electoral system, just as it feels no need to reconcile two totally different visions of justice — “innocent until proven guilty” when it comes to Brett Kavanaugh’s job application and, as Trump told a gathering of police chiefs on Monday, “stop and frisk” for anyone seen as a possible criminal in Chicago (obvious code for a black person walking down the street). This is not seen as a contradiction: There are simply two classes of people — us and them, winners and losers, people deserving of rights and everyone else.