Enabling Genocide

On July 11, 1995, I was in the office of Bosnian Prime Minister Haris Silajdžić in the besieged city of Sarajevo. As Serb artillery shells exploded in the streets around us, we listened to the last radio communication from the U.N. “safe area” of Srebrenica, being overrun by Serb troops led by Gen. Ratko Mladić. There was no doubt among any in the room that widespread killing of Muslims was about to begin.

“This is the result of a twisted policy of containment,” Silajdžić said to me bitterly. “The U.N. contained thousands of our tanks and artillery pieces and disarmed our population. And when we asked why the arms embargo against us could not be lifted, we were told because it would endanger those Muslims living in the protected enclaves. This argument, after these Serb attacks, is now gone. But it means that the U.N. has become an accomplice to murder.”

Thousands of the 42,000 Muslims in the Srebrenica enclave, ostensibly protected by some 400 Dutch troops acting as U.N. peacekeepers, fled the Serbs advancing on the city and congregated in terror at the Dutch base at Potočari, three miles north of Srebrenica. Desperate pleas by the Muslim leadership in Srebrenica to the United Nations and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization for air support were ignored. The Bosnian Serb army, led by Mladić, who last week was sentenced to life in prison by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) on charges of genocide, crimes against humanity and other war crimes, ordered his soldiers to round up thousands of boys and men for execution or hunted them down as they tried to escape to territory under the control of Bosnian Muslims. When the slaughter was complete, more than 7,000 had been slain, the worst war crime in Europe since World War II.

Independence movements in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, a country created at the end of World War II, began to form in the 1990s. The states of Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, Slovenia and Macedonia, with their mix of Orthodox Christian Serbs, Muslim Bosniaks, Catholic Croats and Muslim ethnic Albanians, would all eventually sever ties with Belgrade to create separate nations. Slovenia and Croatia declared independence first, in 1991. When Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence in 1992, the Serbian government in Belgrade intervened militarily on behalf of the Serb minority. Belgrade formed a rival Bosnian government and military, its leadership drawn from the old Yugoslav army, or the JNA. The Bosnian Serb fighters under the command of Mladić had access to the equipment, vehicles, arms and heavy weaponry of the JNA. They mounted a ruthless campaign of ethnic cleansing to drive Bosniak and Croat civilians out of Bosnia in the hope of forming an ethnically cleansed Serb state.

The war in parts of Croatia and Bosnia was savage. The Serbs carried out numerous mass executions of civilians and razed whole villages, often by dynamiting or burning. The war ended in the fall of 1995 with a NATO bombing campaign that crippled the Serbs militarily and forced them to negotiate a peace agreement. An estimated 100,000 people died and 2 million were displaced in the Bosnian conflict.

Bosnia’s capital, Sarajevo, along with five other Muslim-held enclaves, was surrounded by Serb forces. Sarajevo was pounded daily with heavy artillery, mortar rounds, Katyusha rockets and 90 mm tank rounds. Serbian snipers, hidden in buildings in the city’s Serb-held suburbs on the front lines, routinely gunned down civilians emerging from basements to find food or water. The Serbs set up concentration camps where Muslims were tortured, starved and sometimes shot. They commandeered old tourist hotels where they imprisoned Muslim and Croat girls and women and carried out daily rapes, often executing the girls and women after a few weeks.

By the time I arrived in Sarajevo in 1995, thousands of people had been killed, including 45 foreign journalists. The city was being hit with up to 2,000 shells a day. Four or five people were killed and at least two dozen were wounded daily. Sarajevo was my most dangerous assignment in the two decades I worked as a war correspondent.

There were frequent attempts by the European Union to mediate an end to the war, but aside from a few brief cease-fires the fighting continued. At the same time, an arms embargo enforced against the Muslims by the international community crippled the ability of the Muslims to defend themselves. The U.N. eventually established six U.N. “safe areas,” including Srebrenica and Sarajevo. U.N. peacekeepers stationed in these “safe areas” were supposed to protect the besieged Muslims. The peacekeepers, however, were never numerous enough or armed sufficiently to counter Serb attacks. By the end of the war all of the “safe areas” except Sarajevo had fallen to the Serbs.

Mladić, who in three years of war had overseen numerous massacres in the Serb campaign of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia, had announced before the Srebrenica attack that he would make the Bosniak Muslim population of the region “vanish completely.” There was little doubt, given what he had done in the past, about his intentions or his willingness to murder on a large scale.

The stocky general was cynically shown on Bosnian television telling crowds, “No panic, please.” He was shown handing a child a candy bar. “Don’t be afraid,” he said to frightened men, women and children. “No one will harm you.”

But Mladić was only one actor in the cast. The genocide was enabled by France, Britain, the United States, the United Nations and Muslim leaders in Sarajevo. The Western alliance and the United Nations—as in Rwanda a year earlier when it failed to halt the slaughter of 1 million Tutsis by the Hutu majority—never intended to fulfill the promise to protect the surrounded Muslims in Srebrenica.

The U.N. admitted it needed at least 6,000 troops in Srebrenica, yet provided only a token force of 400 Dutch peacekeepers. The U.N.’s special envoy to the Balkans, the Japanese diplomat Yasushi Akashi, and the head of U.N. forces in the area, Gen. Bernard Janvier, blocked airstrikes that might have halted the Serb attack, relenting only in the final moments to make a symbolic strike that did little more than damage a Serb tank. The Serbs, enraged by the airstrike, took 32 Dutch peacekeepers hostage. Airstrikes ceased after the hostages were taken, dooming Srebrenica.

The Dutch soldiers, who had no stomach to fight Mladić’s soldiers without air support, withdrew to their base. They permitted Serb soldiers to enter the base, where thousands of terrified Muslims had sought shelter, and round up men and boys, most of whom were executed, as well as women and girls who were later raped.

At the same time, the paramilitary leader in Srebrenica, Naser Oric, who terrorized Serb villages around the enclave and was later charged with war crimes, had left the city with other commanders before the attack. The Muslim president of Bosnia, Alija Izetbegović, had been told by U.S. President Bill Clinton that if Mladić carried out a massacre in Srebrenica the U.S. would intervene to end the war. Izetbegović either saw the Muslims in Srebrenica as part of the human sacrifice required for NATO intervention, which took place a few weeks later, or he naively believed that the U.N. force would protect the enclave, highly doubtful given the U.N.’s history of refusing to confront the Serbs in three years of warfare. The Clinton administration, we know now, was aware six weeks in advance of the attack that Srebrenica was being targeted by the Serbs but did not intervene out of fear that it would damage ongoing peace negotiations.

Izetbegović had also carried out secret negotiations with Serb President Slobodan Milošević to trade the U.N. “safe areas’ of Goražde, Žepa and Srebrenica, small islands of Muslims trapped in Serb-held territory and nominally protected by the United Nations Protection Force, or Unprofor, for three Serb suburbs around Sarajevo. This exchange of territory was later codified by the Dayton Peace Agreement. Izetbegović was willing, it appears, to give up what he knew he could not defend, despite the loss of life.

The Dutch commander in Srebrenica, Col. Ton Karremans, met Mladić on July 12 and provided 8,000 gallons of gasoline for the Serb trucks and buses that transported boys and men to the killing fields and powered the bulldozers that carved out the mass graves. The scale of the killings was known almost immediately. U.S. intelligence agencies had reconnaissance satellite photographs that showed hundreds of Muslims, blindfolded with their hands tied behind their backs, held at gunpoint by their Serb captors near open pits. There were later photographs of them lying dead in rows. A few days later, photographs showed the fields covered with the freshly dug earth of mass graves. Yet, even as the killings were taking place, the international community did nothing.

The European Union’s special envoy, Carl Bildt, met Mladić and Milošević as the massacres were being carried out and inexplicably decided not to raise the killing as an issue. His chief concern was the Dutch soldiers being held hostage. He was promised they would be released.

Mladić, like Radovan Karadžić and Milošević, is guilty of war crimes. He, as sentenced, should spend the rest of his life in prison. But this act of “justice” is being used to absolve an international community and political leadership, including Muslim leaders, who are complicit. A Dutch court in 2014 found that Dutch peacekeepers were responsible for the deaths of 300 people at Srebrenica, resolving one of several lawsuits related to the genocide. And the Dutch government resigned in 2002 after acknowledging its failure to protect those in Srebrenica. But the Dutch are alone in attempting to accept some responsibility for the killings.

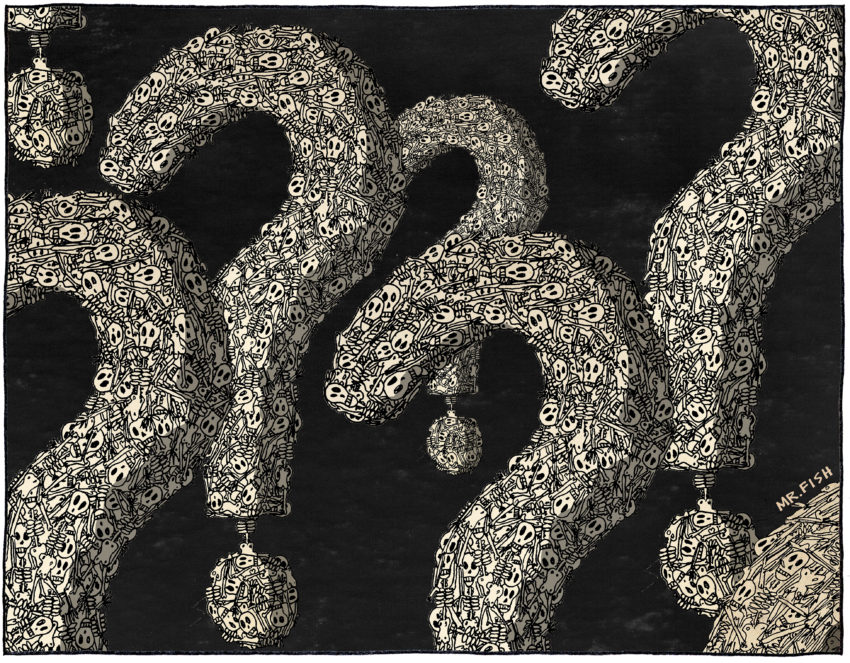

How is it that nearly all the diplomats, politicians, generals and U.N. representatives who are complicit in this genocide have never been held to account? Why were none forced to resign in disgrace? How could the U.N. and the international community promise to protect a population facing genocide and then refuse to defend it? How could they insist on imposing an arms embargo on the Muslims in Bosnia as the Serbs deployed heavy weapons against them? How could the Dutch soldiers hand over civilians, who they had every reason to suspect would be murdered, and then provide the gasoline used in the trucks and buses that transported the men and boys to execution sites? How could the Muslim leadership sacrifice thousands of its own people to achieve the goal of NATO intervention?

The world is not bifurcated into good and evil. The United States too is guilty for the killings at Srebrenica. The refusal to examine and accept our responsibility in this act of genocide means there will be more genocides, as we see with Myanmar’s assault on the Rohingya Muslims and the Saudi campaign against Yemen. We should have learned the central lesson of the Holocaust a long time ago: When you have the capacity to stop genocide and you do not, you are culpable.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten