Jun 16, 2019

A “Top Priority” CIA Project and a Ukrainian Memorial in New Jersey

It was an appropriately somber day that I finally made the trip to South Bound Brook, New Jersey to visit the grave of the Ukrainian nationalist leader Mykola Lebed — a Nazi collaborator and war criminal who worked for the CIA throughout the Cold War — and the memorial he helped establish at St. Andrew’s Ukrainian cemetery. Thirty-five years ago, in 1984, his longtime partner in crime Ivan Hrinioch, a Greek Catholic priest with ties to Nazi and Vatican intelligence before the CIA made him its principal agent in early postwar Ukrainian operations, “led a procession of hundreds of Ukrainians to the unveiling and blessing of [this] memorial dedicated to the unknown soldiers of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA).” The latter, formed in 1943, heroically fought the Nazis and Soviets both, or so it is often said, as the partisan army of the OUN-B, the fanatical Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists led by Stepan Bandera.

In reality, the UPA prioritized the mass murder of Poles and Jews behind Nazi lines in western Ukraine before it terrorized Ukrainian “traitors” and “collaborators” under Soviet occupation. The vast majority of the UPA’s leadership collaborated with Nazi Germany. Contrary to popular belief among many of those critical of US foreign policy and wary of neo-Nazis in Ukraine, it seems the CIA never supported Stepan Bandera. However, the Agency empowered and even propagated OUN-UPA myths by sponsoring a rival “Foreign Representation of the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council” (zpUHVR) led by Lebed and Hrinioch.

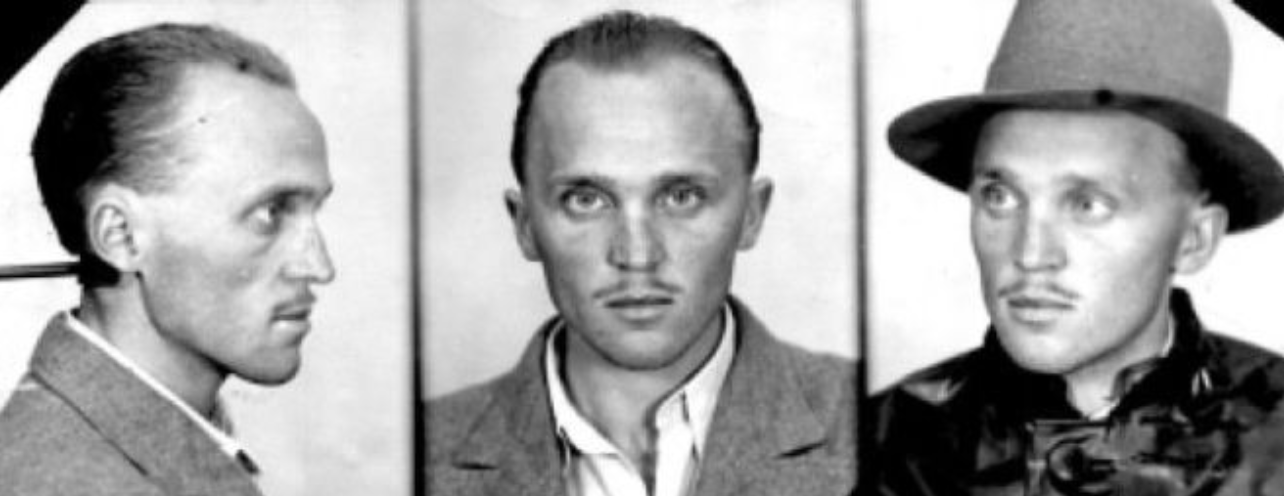

As the de facto leader of the OUN-B during much of World War 2 and an organizer of the UPA who directed the “Banderite” partisans to “cleanse the entire revolutionary territory of the Polish population,” Mykola Lebed was said to be a “known sadist and collaborator of the Germans.” The Central Intelligence Agency denied these and other charges, including his central role in the 1934 assassination of the Interior Minister of Poland, in correspondence with the Immigration and Naturalization Services after smuggling Lebed to New York City in 1949. Months before the 1952 presidential election, the deputy director of the CIA, Allen Dulles, made Lebed a US citizen on the basis that he was involved in “operations of the first importance” and therefore of “inestimable value to this Agency.”

In a 1936 courtroom in Warsaw, Mykola Lebed and Stepan Bandera struck fascist salutes after they were sentenced to life in prison for orchestrating the assassination of the Polish Interior Minister, Bronisław Pieracki. Three years later, during the outbreak of World War 2, they escaped prison under mysterious, chaotic circumstances. In the coming months, as Bandera prepared to make a bid to lead the OUN, Lebed reportedly participated in a “secret Gestapo police-espionage training school” in southern Poland where, according to Tadeusz Piotrowski, “Mykola Lebed was in charge of the Ukrainian unit.” In early 1941, the US government was convinced that the OUN assassin that Lebed handled in 1934 had accepted a mission from the Nazis to kill FDR. A decade later, Mykola Lebed’s well-being was considered an issue of US national security.

Ivan Hrinioch is often overlooked as an important leader of the OUN-B during World War 2. He sustained a relationship with German intelligence officials during the war, including one of Adolf Eichmann’s colleagues, Fritz Arlt — “the Reich’s Jewish-population statistics wizard,” says Edwin Black. Hrinioch told the CIA he helped the Banderivtsi work out “a constructive political program” in 1941, yet the Agency considered him to be “completely uncorrupt” and “a first-class partner in every respect,” not to mention “a hard-headed realist particularly gifted at slow conference table negotiation.” After all, Hrinioch “entered into negotiations with the German Intelligence” on behalf of the UPA in 1944, and three years prior, helped Yaroslav Stetsko, the deputy leader of the OUN-B, obtain the blessings of Andrey Sheptytsky, the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, to declare a Ukrainian state under Nazi occupation.

When the Germans and their Ukrainian collaborators reached Lviv — a prized possession of Austria (1772–1918) and Poland (1349–1772, 1918–1939), also the capital of medieval western Ukraine (the “Kingdom of Halych-Volhynia,” 1272–1349) — just over a week after Hitler declared war on the Soviet Union, the OUN-B tried to establish a Ukrainian Nazi client state. Hoping to avoid that, the Nazis didn’t let Stepan Bandera leave Kraków. Therefore on June 30, 1941 in Lviv, Bandera’s deputy Stetsko made a proclamation on his behalf, hopeful to receive Hitler’s blessings: “The newly formed Ukrainian state will work closely with National Socialist Greater Germany…” Yaroslav Stetsko, as its “Prime Minister,” led a short-lived pro-Nazi coalition government dominated by the OUN-B.

A handful of future zpUHVR leaders were given top posts in this wanna-be quisling regime, including Mykola Lebed as the “Minister of State Security”; Lev Rebet, Stetsko’s “Deputy Prime Minister”; and Volodymyr Stakhiv, the “Minister of Foreign Affairs.” The future Supreme Commander of the UPA, Roman Shukhevych, at that time the Ukrainian leader of the Nachtigall Battalion — an Abwehr (German military intelligence) special forces unit staffed by the OUN-B— was named the Deputy Minister of Defense. Ivan Hrinioch, as the Nachtigall Battalion chaplain, attended Stetsko’s speech dressed in German military garb. The following morning, when the pogrom began, he announced “the renewal of Ukrainian statehood” on Lviv’s airwaves, and read aloud a pastoral letter by the Metropolitan Archbishop endorsing their course of action thus far. (Ten years later, he toured the Ukrainian American community and made numerous speeches from local radio stations.)

On July 1, a catastrophic wave of Nazi-orchestrated pogroms throughout western Ukraine began in Lviv, spearheaded by an OUN-B militia first formed in the courtyard of Sheptytsky’s church. Stetsko called it the Ukrainian People’s Revolutionary Army on June 30, but it was quickly subordinated to the SS, and he was in trouble. Refusing to rescind their declaration of statehood, Bandera and Stetsko were placed under house arrest in Berlin. When the Germans reached the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv, the Nazis began to detain OUN-B members (including Bandera and Stetsko) in concentration camps, albeit as privileged political prisoners. In the meantime, according to Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe,Bandera directed Lebed not to resist but to try to collaborate further with Nazi Germany.

Mykola Lebed ordered the OUN-B to infiltrate the Nazi auxiliary police units throughout western Ukraine. The Banderites who did so received weapons and training from the Germans, not to mention experience on the frontlines of the “Shoah by bullets.” In early 1943, after the Soviet victory at Stalingrad, by which time most Jews in western Ukraine were dead, the OUN-B called on its sleeper cells to abandon their Nazi posts and join the UPA. Shukhevych himself was the commander of Schutzmannschaft Battalion 201 (essentially Nachtigall 2.0). The UPA immediately began its barbaric campaign against Poles, which Jared McBride described as “one of the most violent ethnic cleansing episodes in 20th century Europe.”

In 1943–1944, as it became apparent that the Nazis would lose the war, the OUN-B and UPA began to pin their hopes on gaining the support of the western Allied powers, and adopted a number of superficial reforms aimed at “democratizing” the nationalist movement. Lebed, Shukhevych, and others created a new, nominally anti-fascist “underground government,” the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council (UHVR) — another coalition on paper in fact dominated by the OUN-B.

During the last months of the war, the Nazis released the Ukrainian nationalist leaders they imprisoned, in part to facilitate German cooperation with the UPA. Bandera and Stetsko however rejected the UHVR’s leftward pivot, so they created the “Foreign Units of the OUN” (ZChOUN) in postwar Germany. Making their way to western Europe, Lebed and Hrinioch spearheaded the UHVR’s “Foreign Representation,” which carried itself as the only legitimate government in exile of an anti-Soviet “Ukrainian Resistance Movement” led by the UPA. An intra-party émigré feud simmered until it reached a boiling point in the summer of 1948, when the zpUHVR officially left the OUN-B.

“Although the structure of this government [UHVR, ostensibly operative underground in Soviet Ukraine] appears to be very democratic,” the CIA later observed, “it is in some respects patterned on the Soviet system which allows one party rule…” Stepan Bandera remained the fascist spiritual leader of the OUN-UPA, but until the KGB assassinated him in 1959, he struggled (and failed) to reassert the dictatorial powers he wielded over western Ukrainian nationalists in 1940-1941, and in the process inadvertently helped Soviet intelligence destroy what remained of the OUN-UPA in Ukraine. To some extent, the CIA at first tried to exploit the Ukrainian Insurgent Army as Nazi Germany did, as an anti-Soviet “stay-behind army” actually behind enemy lines — a project probably doomed from the start.

Almost a decade after World War 2 ended, the Agency determined that “if some semblance of a Ukrainian Resistance [UPA] headquarters might still exist, it is possible that it and many of its branches are penetrated by the Soviets.” As told by Christopher Simpson, author of Blowback: The First Full Account of America’s Recruitment of Nazis and Its Disastrous Effect on The Cold War, Our Domestic and Foreign Policy, “In hindsight, it is clear that the Ukrainian guerrilla [UPA] option became the prototype for hundreds of CIA operations worldwide that have attempted to exploit indigenous discontent in order to make political gains for the United States.” But the “Ukrainian guerrilla option” was an unmitigated disaster.

In the end, US aid was given to the [UPA] rebels only insofar as it served short-term American intelligence-gathering objectives, no more. What this meant in strategic terms was that the [Ukrainian] guerrillas … were used as martyrs — some of whom died bravely; some pathetically — and grist for the propaganda mills of both East and West.

In 1951, a year after the death of Roman Shukhevych, the leader of the UPA, the zpUHVR began to publish Suchasna Ukraïna (“Ukraine Today”) in Munich, a bi-weekly Ukrainian-language newspaper subsidized by the CIA and edited by Volodymyr Stakhiv, the former “Minister of Foreign Affairs” in Yaroslav Stetsko’s short-lived, genocidal government. Many years later, Stakhiv admitted that Lebed “asked him to forget and not to mention uncomfortable elements of the past, such as Bandera’s direction to the movement in late 1941 to repair relations with Nazi Germany and to attempt further collaboration with the Nazis.” The zpUHVR was no less interested than the ZChOUN to whitewash their shared history, because there were no moderates in the OUN-B during World War 2. According to Stepan Bandera’s biographer Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, in 1946 Mykola Lebed wrote “perhaps the first comprehensive postwar publication that not only denied the OUN and UPA atrocities but also argued that the UPA helped ethnic minorities in Ukraine, in particular Jews.”

According to Frank Wisner, head of the CIA-tied Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), “In view of the extent and activity of the resistance movement in the Ukraine,” as of 1951, “we consider[ed] this” —exploitation of the UPA — “to be a top priority project.” At the dawn of Operation AERODYNAMIC, in 1952, the CIA regarded the zpUHVR’s efforts to “consolidate” the Ukrainian diaspora “on behalf of the Ukrainian Resistance Movement” among its chief political warfare objectives vis a vis the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The Agency remained optimistic about the UPA’s abilities and US plans to “work toward a rapprochement between zpUHVR-ZChOUN … so that, under our control, the Ukrainian emigration [will] take a united stand against the USSR which would be more consistent with American Foreign Policy.”

Two years later, a less optimistic CIA acknowledged that “it was never determined how extensive the Ukrainian Resistance Movement was at any time during the years of 1948–1953.” The central component of AERODYNAMIC wouldn’t be paramilitary operations, but psychological and political warfare — the Prolog Research Corporation, a CIA front headquartered in Manhattan, with Mykola Lebed as its president. After the CIA gave up on stay-behind operations in Ukraine, the zpUHVR became synonymous with Prolog, which soon enough established itself as “one of the most authoritative Ukrainian publishing houses in the United States.”

When I found Lebed’s grave, I was at first surprised to see him buried next to two other zpUHVR leaders, Yuri Lopatinsky and Myroslav Prokop. I later identified at least three others from the zpUHVR buried here.

Lopatinsky, a former Nachtigall lieutenant, was freed by the Nazis from a concentration camp in October 1944. Two days after Christmas, the Germans parachuted him into western Ukraine to make contact with the UPA. He returned to Germany a year later as the UPA’s liaison to the zpUHVR, and in 1946 made contact with the Strategic Services Unit (SSU), a CIA predecessor, on behalf of the OUN-B. “We…played with these people [Soviet spies] until we got them…and we like them to believe that they actually had penetrated us,” Lopatinsky, a longtime CIA agent in the making, told his SSU contact, introducing him to the OUN-B’s secret police chief Myron Matviyeyko, who had likely already been doubled by Soviet intelligence. Years later Lopatinsky worked as a CIA spotter for Ukrainian “hot war agents,” what Christopher Simpson called “World War 3 guerrillas.” Matviyenko, meanwhile, had helped the Soviets finish off the UPA.

During the 1930s, Myroslav Prokop and Volodymyr Stakhiv worked for an OUN propaganda bureau in Berlin that came under scrutiny from the House Un-American Activities Committee at the start of World War 2. During the Cold War, the CIA employed them and at least two others from the pro-Nazi “Ukrainian Press Service” to propagandize their homeland. Prokop succeeded Lebed as the president of Prolog in 1973.

As told by declassified CIA documents, the zpUHVR changed gears in the second-half of the 1950s when AERODYNAMIC “assumed a mainly media production and distribution role…” Its members, reformed Banderites, gave up on being militant far-right radicals who agitated for Ukrainian independence via armed revolution and World War 3. Embracing pluralism and nonviolence would be the key to their success over other Ukrainian nationalist émigrés — an ability to bridge the gap with Soviet dissidents.

Anatole Kaminsky, a former OUN-B secret police officer turned Prolog chief, once put it this way: “This was a turn towards evolutionary methods of struggle, a peaceful project with the aim of preparing a base for further future struggle…” Prolog’s staple journal, Suchasnist (established in 1961), he boasted, “became the published voice and authoritative voice for Ukrainian human rights defenders and the entire [Soviet] dissident movement in the free world.” In the early 1960s, nearly a decade after Stalin’s death, the zpUHVR made contact with “the Sixtiers,” a dissident literary movement in Soviet Ukraine. Prolog began to publish their savydav (Russian: “samizdat”), contraband literature that the CIA found to “become even more known to the Ukrainian population when smuggled West and subsequently beamed to Ukraine by Western radio stations.”

The Soviet authorities began to wise up in the 1970s, leading the zpUHVR’s contacts to fear “the capabilities of the KGB not solely because of their personal safety, but because the small number of hard-core dissidents are so well known that … mass arrests … would emasculate if not annihilate the entire Ukrainian dissident movement.” Nevertheless, the CIA persisted, and a KGB “clampdown” began in January 1972. “According to our project sources in the Ukraine,” the CIA noted a year later, “it will take some time for the populace in general to recover from their present paralysis,” but the Agency remained optimistic: “Mykola Lebed has not lost the confidence of the Ukrainian democratic movement… [and] they still count heavily upon his organization for material and moral support.”

Looking on the bright side, “the arrests of 1972 have been greatly responsible for the stepping-up of the Ukrainian youth activities in the West,” and Prolog “has earned the respect of prominent Ukrainian dissidents, most of whom have been imprisoned by the KGB…” In 1977, President Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, made aware of AERODYNAMIC a decade prior, “requested that the existing covert action [program] against the Soviet Union and East Europe be beefed up…”

Under the Reagan administration, the Central Intelligence Agency understood the “goal” of its principal Ukrainian operation (renamed PDDYNAMIC) to be “to publish and infiltrate into the USSR literature aimed at keeping alive the Ukrainian nationalist spirit, and to support [democratic] Ukrainian groups who oppose Soviet policy…” During the CIA’s 1981 fiscal year, Prolog infiltrated some 17,500 pieces of literature into the Soviet Union, and published “ten new works,” including The Restless Autumn, “a novel based upon the author’s experiences during the Ukrainian partisan army [UPA]’s struggle…” and Pogrom in Ukraine, “a collection of samizdat documents dealing with the dissident trials of 1972 in Ukraine.” Meanwhile, the CIA planned to “increase [Prolog’s] program of reprinting mini-editions of selected issues of Suchasnist as well as pocket editions of [Prolog] reprints, especially works dealing with Ukrainian partisan [UPA] activities during World War 2.”

In 1982, the zpUHVR sent over 27,000 pieces of literature to the USSR — although how much of it reached Soviet citizens is unclear — and began to develop new methods of smuggling “product,” such as “the infiltration of proscribed literature using books which appear to be real titles acceptable to the Soviet regime but which, in fact, have interchangeable centers.” The CIA distributed Mykola Lebed’s whitewashed history of the UPA in this fashion. In 1983, Prolog reprinted, among other “classic” works, Litopys UPA (“Chronicle of the UPA”), “a documentary history of the Ukrainian Partisan Army (UPA),” and In the Forest of the Lemko Region, a novel by Ivan Dmytryk “which deals with the UPA struggle.”

As the KGB took further measures to crackdown on the CIA book program, the Soviet press launched a “full-scale attack on Ukrainian nationalism under the name of [a] ‘counter-propaganda campaign.’” So the zpUHVR pivoted towards “other devices…stickers, cassettes, etc.” In 1984, the year of the UPA memorial’s unveiling in New Jersey, the CIA infiltrated 268 tape cassettes into Soviet Ukraine, half of them UPA songs. In his 1989 book Blowback, Christopher Simpson observed, “Today, more than forty years after the end of the war, Soviet propaganda still tags virtually any type of nonconformist in the Ukraine with the label of ‘nationalist’ or ‘OUN,’ producing a popular fear and hatred of dissenters that is not entirely unlike the effect created by labeling a protester a ‘Communist’ in American political discourse.”

Ivan Dmytryk, a Suchasnist contributor, is among the forty other UPA veterans buried in South Bound Brook, New Jersey. In addition to Lebed, Prokop, and Lopatinsky, the same goes for at least three other members of the zpUHVR: Bohdan Kruk, Mykola Haliw, and Lev Shankovsky. This means at least a handful of CIA assets were buried here, and perhaps significantly more. It’s certainly possible that a large share of those buried in the UPA section of St. Andrew’s Ukrainian cemetery were affiliated with the CIA-backed zpUHVR, as opposed to the Bandera/Stetsko-led ZChOUN/OUN-B.

According to Stephen Dorril, Bohdan Kruk was “sometimes referred to as the Director of the UPA [Medical Service and/or OUN-B] Red Cross,” led the OUN-UPA effort to “pacify the [Galician] countryside” of “Soviet partisan activity” in late 1943, and was an early member of the zpUHVR. Kruk participated in the UPA’s 1947 “Great Raid to the West,” that is, the American Zone of occupied Germany, from which he and others eventually resettled in the United States and elsewhere. Mykola Haliw’s grave has “zpUHVR” on the tombstone, and declassified CIA files indicate the Agency had some sort of interest in him, at least in 1962.

“OUN historian” Lev Shankovsky, another early member of the zpUHVR, and a “special correspondent” for Suchasnist, joined an AERODYNAMIC “Psychological Warfare Panel” chaired by Mykola Lebed in the 1950s. Among other things, it was tasked to “begin a systematic collection of names of personalities in the Ukraine who the panel feels have been designated as Soviet ‘sleepers’ in the Ukraine. In the event of a hot war and should the Ukraine be occupied by a Western power, these people will propagate the Soviet cause.” (During World War 2, Lebed supplied Nazis the names of Polish professors who were then shot.) In 1960, Shankovsky declared that organized anti-Semitism “never existed in Ukraine. But there exists a myth about Ukrainian anti-Semitism.”

Also buried among the Ukrainian Insurgent Army veterans at St. Andrew’s Ukrainian cemetery in South Bound Brook, New Jersey is the late chairman of its UPA “memorial building committee,” Julian Kotlar, a former executive publisher and vice-chair of “Litopys UPA.” The latter began as a revisionist history project “published jointly by two UPA veterans’ organizations,” one Canadian and the other from the United States. In the 1970s, the CIA was happy to report that “many student groups and intellectuals [in North America] have established close ties” with the zpUHVR, which was then affiliated with the Association of Former Members of the UPA in the US and Canada, plus two obscure “civic organizations [the Association for Free Ukraine and Ukrainian-Canadian Society]…which have branches in various cities in both countries.” A former head of the Litopys UPA “publication committee” and “the so-called ‘spiritus movens’ behind the entire endeavor,” Dr. Modest Ripeckyj of Chicago, was (formerly, if not actively) a member of the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council. “I don’t know how the heck we are going to proceed, because he was extremely important to the project,” a leader of the Canadian UPA veteran society said when Ripeckyj died in 2004.

That being said, Litopys UPA and the organized UPA vets were probably more influenced by the OUN-B than the zpUHVR. By 2001, the “Chronicle of the UPA” found a new friend in the notoriously problematic Volodymyr Viatrovych, who is affiliated with the present-day OUN-B. If not already, he was soon made the deputy director of a “Litopys UPA Publishing House” in Lviv, and in 2002 became the director of an OUN-B “Center for Research of the Liberation Movement,” also in Lviv. As it were, the archives of the zpUHVR’s Prolog Research Corporation, which shut down in 1992, are today at the OUN-B Research Center. From 2008 to 2010, Viatrovych directed the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU)’s archives, after which Harvard University’s Ukrainian Research Institute invited him to study Mykola Lebed’s papers. Following the 2013–2014 “Revolution of Dignity,” Viatrovych was appointed to head the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance. In 2015, he participated in several events with Ukrainian-American leaders honoring Stepan Bandera and the OUN-UPA in the United States.

In 1985, the CIA decided “the time has come to notify a senior level of the Department of Justice of the developments surrounding … Mykola Lebed,” then under investigation for war crimes by the DOJ’s Office of Special Investigations (OSI). The CIA once again declared him innocent, as it had in the early 1950s: “we have no basis to believe that Mr. Lebed was a Nazi collaborator…” When the New York Times phoned his apartment in Yonkers, a man answered the phone who “identified himself as Mr. Lebed’s landlord for the last 15 years and said his tenant had left this week for vacation with his wife, who is ill.” This “landlord, Ivan Hirnyj,” is buried with the other UPA veterans in Somerset County, New Jersey. He told the New York Times that “Mr. Lebed was working for the American Government but that he did not know in what capacity.”

Fortunately for Lebed, the CIA observed, “OSI does not seem to be developing a viable case,” so he remained “closely associated” in an advisory capacity with CIA operations targeting Ukraine. According to Richard Breitman and Norman JW Goda, “As late as 1991 the CIA tried to dissuade OSI from approaching the German, Polish, and Soviet Governments for war-related records related to the OUN. OSI eventually gave up on the case, unable to procure definitive documents on Lebed.” He died a free man in 1998. Standing before his grave and the “Unknown Soldiers of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army” memorial a month ago, I remembered that Lebed was a member of the aforementioned “building committee,” and it seemed clear to me that the memorial was probably incomplete, in his view, until they buried him beside it some years later.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten