The Lessons of the Taliban

•

The U.S. humiliation in Afghanistan shows that the empire can’t impose its will, no matter how much violence it inflicts, writes As`ad AbuKhalil.

Zalmay Khalilzad, left, the U.S. chief envoy, signs off on peace deal with Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, a Taliban leader, in Doha, Qatar, Feb. 29, 2020. (State Department)

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

Special to Consortium News

It was quite a spectacle for this century. If Western media were not all tied to the war establishment, they would have commented on the symbolism: a U.S. envoy signing a peace agreement with an official representatives of the Taliban movement.

Had Osama bin Laden been alive, he may have been invited to the signing ceremony. Younger readers did not live through the massive propaganda campaign by all Western governments against the Taliban back in 2001. The U.S. war on Afghanistan was very popular then: at least 90 percent of Americans supported it in 2001.

Conservatives and liberals united to convince public opinion that the removal of the Taliban from power was an American national priority. The liberal organization, the Feminist Majority, aided the White House in its propaganda effort by releasing information on the Taliban’s war on women.

But when U.S. bombs started to kill women and children on a regular basis, the Feminist Majority and other liberals were silent. (Among women’s rights activists — including some in Afghanistan — the Feminist Majority’s pro-military position on Afghanistan was controversial at the time.)

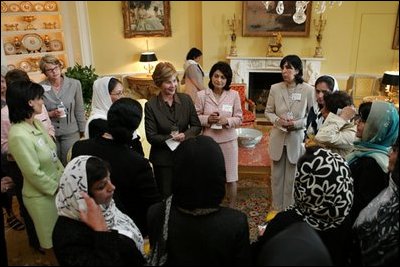

George W. Bush and his wife briefly posed as feminist in an effort to persuade the public that the American invasion of Afghanistan is a humanitarian effort.

Disinformation About US Pretexts

First Lady Laura Bush meets with members of the State Department’s U.S.-Afghan Women’s Council, June 15, 2004. (The White House, Tina Hager)

Much of the history of the U.S. war in Afghanistan is yet to be written. So much disinformation surrounded the U.S. pretexts. The U.S. said that it was invading Afghanistan because the Taliban government did not surrender bin Laden to the U.S. In reality, the Taliban government said at the timethat it would consider a U.S. request to surrender bin Laden if the U.S. would show evidence of his complicity in Sept. 11 (and the Taliban government reached the decision after holding a national tribal conference). But the U.S. was not going to negotiate with the Taliban once the decision to invade was taken.

What is curious about the case of the Taliban is that the U.S. did not object to the Taliban’s seizure of power back in 1996. By 2001, only three governments in the world recognized the Taliban’s government and all were close clients of the U.S. (UAE, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia). Prince Turki Faisal (the head of Saudi foreign intelligence until days after Sept. 11) was one of the few officials in the region who had met with the Taliban-founder and leader Mullah Omar and who had longstanding relations with bin Laden. In the summer before Sept. 11, the U.S. had praised the Taliban’s war on opium.

All this now seem to read like a conspiracy theory with no basis in reality, but the long U.S. history in Afghanistan stretches to the time when the U.S. decided that its war against the Soviets in Afghanistan would be more important than the welfare of the Afghan people. When the Soviet Union was supporting secularism, feminism and modernity in Afghanistan, the U.S. was on the side of fundamentalism, obscurantism and reactionary organizations wishing to bring back the Middle Ages. The U.S., after all, was in the same trench with bin Laden.

Taliban Gained Popularity

The U.S. quickly dislodged the Taliban government but never really took over the country. The popularity of the Taliban (especially among the Pashtuns) was never in doubt; and the government that the U.S. set up in Afghanistan even increased the popularity of the Taliban further.

The Taliban, while reactionary, repressive, and misogynistic, never engaged in the corruption that has plagued Afghanistan ever since the U.S. set up a government there. And the U.S. fought the war with reckless disregard for the lives of the Afghan people: year after year, the UN was chronicling the number of civilian casualties caused by U.S. bombing (and by the bombing of the Taliban although there are years when U.S. bombs caused more civilian casualties than Taliban bombs). In the first year of the war, the U.S. Central Command was bragging about the pin-point accuracy of its bombs, that “only” 25 percent of its bombs and missiles had missed their targets.

“The U.S. will draw the same lessons it drew from Vietnam: that not enough force was used against the natives, and that the U.S. press was not committed enough to the occupation project.”

From the second year of the war at least, the U.S. knew that its puppet government would stand no chance of surviving without direct U.S. occupation of the country. The Taliban quickly regrouped and mounted a fierce insurgency against the U.S. occupation force and the puppet government.

Western media helped to cover up U.S. war crimes in Afghanistan (and the war crimes by its clients in the Afghan government and the so-called Northern Alliance before the ouster of the Taliban). Instead of paying attention to civilian casualties, U.S. media were filled with stories on how women were now “liberated,” although little difference was made by the U.S. presence given the U.S. alliance with reactionary forces in society.

The U.S. lost the war in Afghanistan just as it lost the war in Iraq, and just as the U.S. and its allies have lost the war in Yemen. Those three cases should be a lessons for the U.S. empire: that no matter how much massive violence the U.S. inflicts on a population, it can’t bring about its surrender.

Attendees at the Taliban-U.S. peace signing ceremony in Doha, Qatar, on Feb. 29, 2020. (State Department/Ron Przysucha)

Avoiding a Vietnam Spectacle

The lesson of the three wars is that, while the military apparatus of empire has achieved tremendous development and advancement, the military capabilities of the enemies of the empire have also advanced a great deal. The U.S. did not leave Iraq willingly and it won’t be leaving Afghanistan willingly. The U.S. is leaving Afghanistan defeated, but the patriotic media won’t admit the obvious. The U.S. had long lost the war in Afghanistan, but has only stayed to avoid the spectacle of defeat in a nation still suffering from the humiliation of the Vietnam War.

Since the U.S. knew that the puppet government it set up in Kabul wouldn’t last for weeks after the withdrawal of the U.S. troops, scenes of Hanoi had to be avoided at all cost. The process of negotiations with the Taliban started under the Obama administration and reached its culmination under President Donald Trump. Perhaps Obama did not have the political courage to withdraw and probably left the problem for his successor; the Qatari government hosted the Taliban’s office at U.S. behest, and it introduced both sides to each other.

“The U.S. had long lost the war in Afghanistan, but has only stayed to avoid the spectacle of defeat in a nation still suffering from the humiliation of the Vietnam War.”

The significance of the Afghanistan humiliation is the clear evidence that the U.S. can’t impose its will, no matter how much violence it inflicts. Trump arrogantly declared that the war could have been won had the U.S. abandoned a reluctance to kill a million people. But that was tried in Iraq (where a million Iraqis were killed), and the U.S. still could not win there. The debates over the defeat in Afghanistan will go on for decades but the U.S. is unlikely to admit defeat, and the U.S. will try (as it did after Vietnam and after Iraq) to blame technical reasons or bad press for its inability to achieve success.

Ironically, despite the debacles of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. empire won’t retreat. If anything, the U.S. will draw the same lessons it drew from Vietnam: that not enough force was used against the natives, and that the U.S. press was not committed enough to the occupation project.

But the U.S. press could not have been more supportive. From the start — in both Iraq and Afghanistan — much of the press strove to provide pretexts and false evidence to justify the invasion of both countries. In the case of Afghanistan, they pretended the Taliban were themselves behind Sept. 11 (when no evidence was ever presented and it is unlikely the Taliban knew about the plot). Later they pretended that Saddam Husayn himself was behind Sept. 11.

A staggering 70 percent of the American public believed in 2003 that Saddam had a role in Sept. 11, when in fact, Al-Qa`idah had no presence in Iraq prior to the U.S. invasion of the country and the dismantling of Saddam’s security apparatus. The public only linked Saddam to Sept. 11 because the government and the media obfuscated the truth for political reasons.

The U.S. may leave Afghanistan but the U.S. will maintain a military presence (in various forms in 800 bases around the world). The U.S. may retreat from Afghanistan, and even Iraq when the pretext of fighting ISIS withers away, but the war empire is as entrenched as ever. The Democratic presidential debates have demonstrated that the war empire enjoys bipartisan support.

But just as the U.S. is determined to impose its hegemony on a global scale, foes of the empire are as determined to reject U.S. dictates by all means necessary.

As’ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the “Historical Dictionary of Lebanon” (1998), “Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), and “The Battle for Saudi Arabia” (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

If you value this original article, please consider making a donation to Consortium News so we can bring you more stories like this one.

Before commenting please read Robert Parry’s Comment Policy. Allegations unsupported by facts, gross or misleading factual errors and ad hominem attacks, and abusive or rude language toward other commenters or our writers will not be published. If your comment does not immediately appear, please be patient as it is manually reviewed. For security reasons, please refrain from inserting links in your comments, which should not be longer than 300 words.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten