How one article capsized a New York literary institution

A controversial piece by Jian Ghomeshi in the New York Review of Books cost editor Ian Buruma his job and sparked a debate about free speech

For decades, the New York Review of Books has enjoyed a reputation as the most important intellectual publication in the US, a home for complex and challenging ideas.

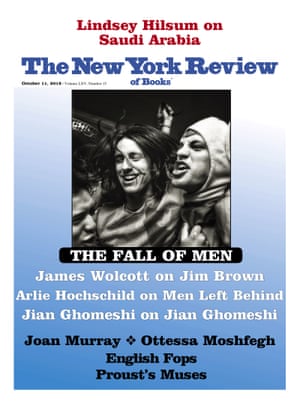

This week, the stately magazine has been capsized after choosing to publish a highly contentious piece by the former broadcaster Jian Ghomeshi, who has been accused of sexual assault by more than 20 women.

Ghomeshi’s article will not be printed until 11 October but it has already cost editor Ian Buruma his job, prompted a detailed apology from the NYRB’s publisher, divided the staff at its West Village office and generated a storm of criticism which has drawn in some of the biggest names in the literary world.

One of the women who accused Ghomeshi of attacking her told the Guardian she was distressed by the article in which, she said, her alleged attacker tried to elicit sympathy and gave a false account of the legal process.

“This is so self-absorbed that I don’t know how this could be published and not cause an outrage,” Linda Redgrave said.

Ghomeshi was fired from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 2014 after multiple complaints of harassment, which included allegations of hitting, biting and choking during sex. He was acquitted in one criminal trialand a second criminal case did not proceed after he signed a “peace bond” and gave one woman a public apology.

In his article for the NYRB, Ghomeshi attempts to “inject nuance” into his story and says “there has indeed been enough humiliation for a lifetime” before ending his account with a “reformed character” anecdote about meeting a woman on a train. He apparently claims ethical credit by describing how he did not try to seduce her.

Redgrave, who waived her right to anonymity after the first criminal trial, said of Ghomeshi’s article: “I had not seen this coming. I suspected that he wasn’t going to go away disgracefully, but it caught me off stride and I was really upset by it. There really wasn’t any apologising, it was trying to just evoke sympathy for something he doesn’t deserve.”

After reading the piece online, she contacted Buruma and demanded to write a rebuttal. He agreed and she filed her account the day before he left the NYRB. She has since been assured that her rebuttal will be published in the 25 October edition as part of a pledge by the magazine to devote “substantial space” to responses to the Ghomeshi article.

Asked if she thought Buruma should have lost his job, Redgrave said: “Yes I do. There is an ethical line you don’t cross. I think he crossed the line. This was something he did knowing that it was going to have this result. He knew that this was wrong, he did it anyway, he deserved to be fired.”

‘Free exploration of ideas’

The article, published online earlier this month, has attracted little conspicuous public support. But the “enforced resignation” of Buruma has divided observers. The affair has also illuminated some of the most difficult questions of the moment:

This week, a letter with 109 signatories, including authors Colm Tóibín, Joyce Carol Oates and Ian McEwan, was sent to the NYRB. It said: “We find it very troubling that the public reaction to a single article, ‘Reflections from a Hashtag’ – repellent though some of us may have found this article – should have been the occasion for Ian Buruma’s forced resignation.

“Given the principles of open intellectual debate on which the NYRB was founded, his dismissal in these circumstances strikes us as an abandonment of the central mission of the Review, which is the free exploration of ideas.”

The letter was coordinated by writer and academic John Ryle and drafted and edited by a core group of 15 contributors. A source with knowledge of how the letter was brought together said it was first distributed via email last Sunday and more than 100 prestigious contributors to the NYRB were given 24 hours to sign or decline.

A second source with knowledge of the letter, who also declined to be named, said: “There was an intense process of revision. I do not know how many of the signatories think that publishing the piece was an error of judgment. The phrasing of the letter embraces those who do think this and those who do not.

“It affirms that, either way, the signatories do not think that there was a justification for summary dismissal … this is a difficult situation, with strong feelings on all sides. But it is clear to me that an injustice has been done to Ian Buruma.”

Buruma, 66 and described to the Guardian by one supporter as “a terrific public intellectual”, claimed in an interview with the Dutch magazine VN he had been “convicted on Twitter, without any due process”. He said be felt compelled to resign, after just over a year in post.

The letter from authors and writers in support of him was made public the day after a detailed statement was released by the NYRB’s publisher, Rea Hederman, rejecting the allegation that public outcry alone was responsible for Buruma’s departure.

“We acknowledge our failures in the presentation and editing of his story,” Hederman said, citing editorial lapses including a failure to bring female members of staff into the editing process. “We surely had a duty to acknowledge the point of view of the women who complained of Mr Ghomeshi’s behaviour.”

The publisher’s statement said many of the editorial staff objected to Buruma’s claim in two interviews that staff came together after initial objections to the piece.

“Finally, it is inaccurate that Ian Buruma’s departure was the result of a ‘Twitter mob’,” the statement said. “In fact before his departure, the mob mostly had moved on.”

‘I believe the women’

The Guardian contacted a number of the signatories to the supportive letter. Joyce Carol Oates said by email she totally agreed with critics of Ghomeshi’s essay, but said: “I thought that terminating Mr Buruma’s contract so abruptly was not a good, or necessary decision. Mr Buruma (whom I don’t know) is a distinguished critic, writer, editor who is certainly to be defined by far more than a single misstep. We would all wish to be given a second chance.”

Fintan O’Toole, literary editor of the Irish Times, who signed the letter, said the published piece was very poor and Buruma should not have said that the truth of the allegations was not his concern.

“So the issue for me isn’t whether he was right or wrong – to me he was clearly wrong. It’s whether one bad incident justifies the sacking of an editor who is very widely agreed to have been doing a very fine job. If editors are sacked the first time they make a mistake, we’ll end up with nobody in charge of vitally important publications except ultra-cautious hacks.”

The rights and wrongs of the piece and Buruma’s fate split other commentators.

Rebecca Solnit, author of Men Explain Things To Me, said: “There are two things that are really outrageous. The first is to give a platform to somebody who appears to have so violated the rights of others and the rights, the dignity, the safety of the bodies of other human beings.

“And the second is to violate all normal editorial standards not only to publish a piece that’s profoundly dishonest and misleading about what happened but to also, according to reports, deny the longtime women editors the rights to have a look at it.”

She added: “I believe the women who made allegations against Ghomeshi and to lose their voices out of the story and let him tell the stories in ways that contradict what they told us: it treats what he has to say as important and true and treats what they have to say as unimportant and irrelevant.”

Gerald Howard, an executive editor at publisher Doubleday, said the NYRB was “immensely important to American intellectual life, which always feels on the edge of disappearing”, but publishing the article was an editorial misfire.

“It was not adequate to the case. I can see exactly why people are upset about it, I don’t think he [Ghomeshi] remotely came to terms with what he did and why he found himself in the situation that he did. It’s substandard without any question.”

But Howard said of the enforced resignation of Buruma: “I really disapprove. I feel that he was taken down by a mob and did not deserve it.

“The thing that especially upsets me is that apparently there was all this pressure from university presses who said they were going to withdraw their ads from the Review because of publishing this piece, which just makes steam come out of my ears.”

Jay Rosen, who teaches journalism at NYU and writes the blog PressThink, said: “A piece that was that provocative and was going to be looked at very closely, because it’s unusual for the New York Review to do something like that, it just needed to be more solid than it was.”

He said it would be a tragedy if the NYRB was to begin shying away from publishing controversial subjects, “but it is not clear that’s what happened. It’s a valid concern about ideas being shouted down on social media and publishers not wanting the cost of that. I’m not saying it’s relevant to this piece but it is something to worry about – it’s good that writers are worried about that.”

Speaking on background because they were not authorised to comment publicly, a member of NYRB staff said most co-workers were relieved the editor had gone, having been concerned about some of his decisions.

In an editorial meeting, objections were raised about the Ghomeshi piece: about its tone and style, about its lack of insight and about the way it misrepresented the allegations against him. After publication, the source said, some staff expressed longstanding concerns to the publisher.

It was distressing Buruma’s departure had become a free-speech issue, the source added, saying it was really about managerial and editorial shortcomings.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten