US Can’t Deal with Defeat

In the U.S., the strongest collective memory of America’s wars of choice is the desirability – and ease – of forgetting them. So it will be when we look at a ruined Ukraine in the rear-view mirror, writes Michael Brenner.

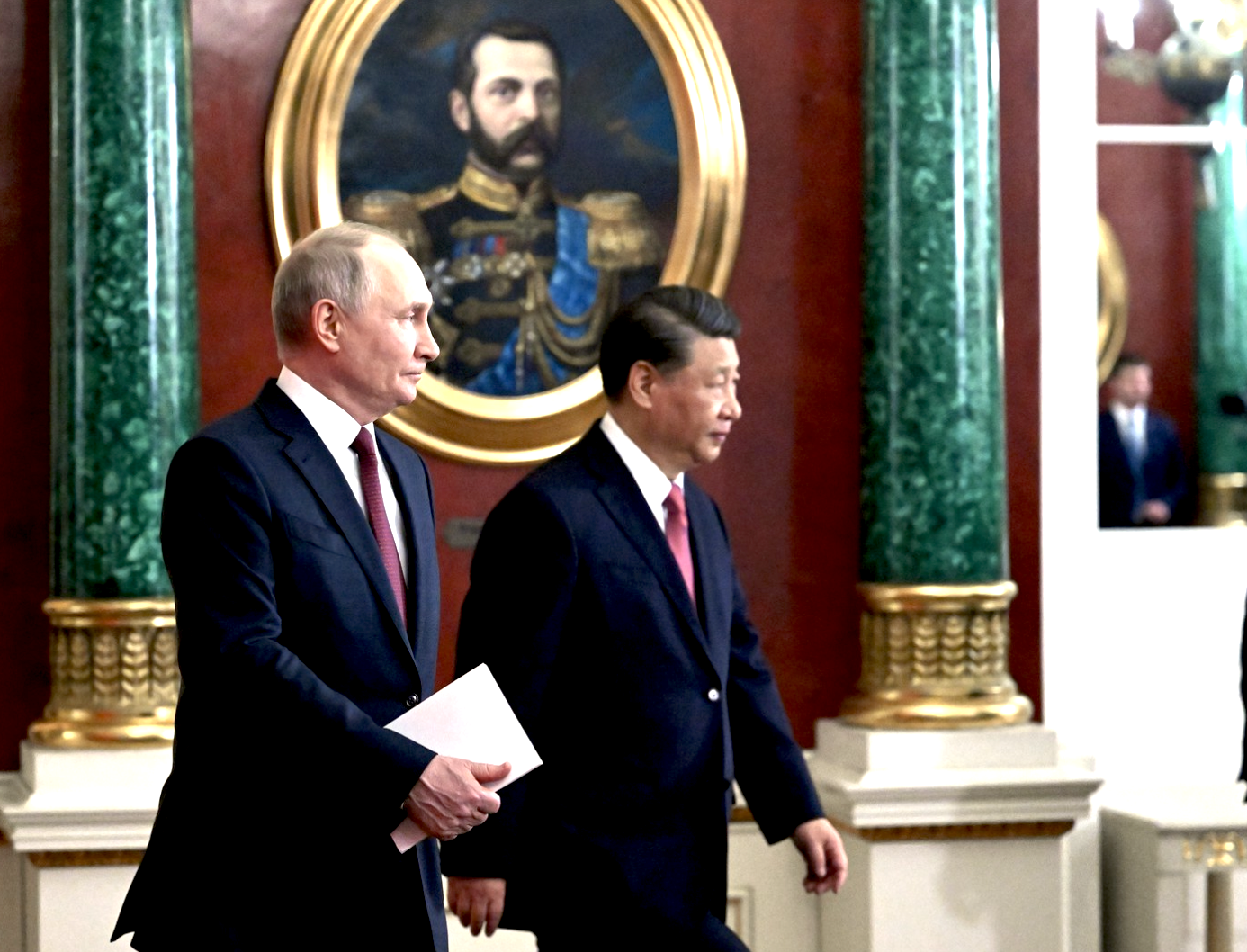

Russian President Vladimir Putin and China’s President Xi Jinping during talks in Moscow in March 2023. (Vladimir Astapkovich, RIA Novosti)

By Michael Brenner

Special to Consortium News

The United States is being defeated in Ukraine.

The United States is being defeated in Ukraine.

One could say that it is facing defeat — or, more starkly, that it is staring defeat in the face. Neither formulation is appropriate, though. The U.S. doesn’t look reality squarely in the eye. It prefers to look at the world through the distorted lenses of its fantasies. It plunges forward on whatever path it’s chosen while averting its eyes from the topography it is trying to traverse. Its sole guiding light is the glow of a distant mirage. That is its lodestone.

It is not that America is a stranger to defeat. It is very well acquainted with it: Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria — in strategic terms if not always military terms. To this broad category, we might add Venezuela, Cuba and Niger. That rich experience in frustrated ambition has failed to liberate Washington from the deeply rooted habit of eliding defeat. Indeed, the U.S. has acquired a large inventory of methods for doing so.

Defining & Determining Defeat

Before examining them, let us specify what we mean by “defeat.” Simply put, defeat is a failure to meet objectives — at tolerable cost. The term also encompasses unintended, adverse second-order consequences.

No. 1. What were Washington’s objectives in sabotaging the Minsk peace plan and cold-shouldering subsequent Russian proposals, provoking Russia by crossing a clearly demarcated red line, pressing for Ukraine’s membership in NATO, installing missile batteries in Poland and Rumania, transforming the Ukrainian army into a potent military force deployed on the line-of-contact in the Donbass ready to invade or goad Moscow into preemptive action?

U.S. Navy base in Deveselu, Romania, home to NATO’s Aegis Ashore Ballistic Missile Defense System site, 2019: . (U.S. Navy, Amy Forsythe, Public domain)

The aim was to either pin a humiliating defeat on the Russian army or, at least, to inflict such heavy costs as to cut the ground from under the Putin government.

The crucial, complementary dimension of the strategy was the imposition of economic sanctions so onerous as to implode a vulnerable Russian economy. Together, they would generate acute distress leading to the deposing of Russian President Vladimir Putin — whether by a cabal of opponents (disgruntled oligarchs as the spearhead) or by mass protest.

It was predicated on the fatally ill-informed supposition that Putin was an absolute dictator running a one-man show. The U.S. foresaw his replacement by a more pliable government ready to become a willing but marginal presence on the European stage and a non-player elsewhere. In the crude words of one Moscow official, “a tenant-farmer on Uncle Sam’s global plantation.”

No. 2. The taming and domestication of Russia was conceived as a vital step in the impending great confrontation with China — designated the systemic rival to U.S. hegemony. Theoretically, that objective could be achieved either by enticing Russia away from China (divide and subordinate) or totally neutralizing Russia as a world power by bringing down its stiff-backed leadership. The former approach never went beyond a few desultory, feeble gestures. All the chips were placed on the latter.

No. 3. Ancillary benefits for the United States from a war over Ukraine that would bring Russia low were a). to consolidate the Atlantic alliance under Washington’s control, expand NATO and open an unbridgeable abyss between Russia and the rest of Europe that would endure for the foreseeable future; b). to that end, the termination of the latter’s heavy reliance on energy resources from Russia; and c). thereby, substituting higher-priced LNG and petroleum from the United States that would seal the European partners’ status as dependent economic vassals. If the last were a drag on their industry, so be it.

The grandiose goals stated in No. 1 and No. 2 manifestly have proven unreachable — indeed, fanciful — a blunt truth not as yet absorbed by American elites. Those in No. 3 are consolation prizes of diminished value. This outcome was determined in good part, albeit not at all entirely, by the military failure in Ukraine.

We now are about to enter the final act. Kiev’s vaunted counter-offense has gone nowhere — at an enormous cost to the Ukrainian military. It has been bled white by massive losses of manpower, by the destruction of the greater part of its armor, by the ruin of vital infrastructure.

Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken place a memorial wreath at a cemetery in Kiev on Sept. 6. (State Department, Chuck Kennedy, Public Domain)

The Western-trained elite brigades have been mauled and there are no longer any reserves to throw into the battle. Moreover, the flow of weapons and ammunition from the West has slowed as U.S. and European stocks are running low (e.g. 155mm artillery shells).

The shortage is being aggravated by newfound inhibitions about sending Ukraine advanced weapons which have proven highly vulnerable to Russian fire. That holds especially for armor: German Leopards, British Challengers, French AMX-10-RC tanks as well as Combat Fighting Vehicles (CFV) like the American Bradleys and Strykers.

Graphic images of burnt-out hulks littering the Ukrainian steppe are not advertisements for either Western military technology or foreign sales. Hence, too, the slow-walking of deliveries to Kiev of the promised Abrams and F-16s lest they suffer the same fate.

Illusion of Eventual Success

The illusion of eventual success on the battlefield (with its envisaged wearing down of Russia’s will and capacity) is founded on a mistaken idea of how to measure winning and losing.

American leaders, military as well as civilian, are stuck to a model that emphasizes control of territory. Russian military thinking is different. Its emphasis is on the destruction of the enemy’s forces, by whatever strategy is suited to the prevailing conditions. Then, in command of the battlefield, they can work their will.

The aggressive tactics of the Ukrainians entail throwing its resources into combat in relentless campaigns to evict the Russians from the Donbass and Crimea.

Unable to achieve any breakthrough, they invited themselves to a war of attrition much to their disadvantage. It has been succeeded by this summer’s all-out last fling which has proven suicidal. They thereby played into the Russians’ hands. Hence, while attention is fixed on who occupies this village or that on the Zaporizhhia front or around Bakhmut, the real story is that Russia has been dismantling the reconstituted Ukrainian army piece by piece.

Sumy, Ukraine, after Russian drone strike on July 3. (National Police of Ukraine, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

In historical perspective, there are two instructive analogies. In the last year of World War I, the German high command launched an audacious campaign, Operation Michael, on the Western Front in March 1918 using a number of innovative tactics (featuring commando squads and stormtroopers equipped with flame-throwers) to punch holes in allied lines. After initial gains that brought them across the Marne, attended by very heavy casualties, the offensive petered out and allowed the allies to roll over their gravely depleted forces— leading to the final collapse in November.

More pertinent is the Battle of Kursk in July 1943 wherein the Nazis made a massive attempt to regain the initiative after the disaster at Stalingrad. Again, after some noteworthy success in breaching two Soviet defense lines they exhausted themselves short of their objective. That battle opened the long, bloody road to Berlin.

German soldiers pause during the Battle of Kursk. (Bundesarchiv, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0 de)

Ukraine, today, has suffered huge losses of even greater (proportional) magnitude, without achieving any significant territorial gains, unable even to reach the first layer of the Surovikin Line. That will clear the road to the Dnieper and beyond for the 600,000 strong Russian army equipped with weaponry the equal of what the West has given Ukraine. Hence, Moscow is poised to exploit its decisive advantage to the point where it can dictate terms to Kiev, Washington, Brussels et al.

The Biden administration has made no plans for such an eventuality, nor have its obedient European governments. Their divorce from reality will make this state of affairs all the more stunning — and galling. Bereft of ideas, they will flounder. How they will react is unknowable. We can say with certainty one thing: the collective West, and especially the U.S., will have suffered a grave defeat. Coping with that truth will become the main order of business.

Here is a menu of options for handling it:

Redefine what is meant by defeat, victory, failure, success, loss, gain.There is a new narrative that is scripted to stress these talking points:

- It is Russia that has lost the contest because heroic Ukraine and a steadfast West have prevented it from conquering, occupying and reincorporating all of the country.

- By contrast, Sweden and Finland formally have joined the American camp by entering NATO. That complicates Moscow’s strategic plans by forcing a dispersion of its forces across a wider front.

- Russia has been politically isolated on the world scene. That is because North America, E.U./NATO-Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand have backed the Ukrainian cause. Not a single other country has agreed to apply economic sanctions; the “world” does not include China, India, Brazil, Argentina, Turkey, Iran, Egypt, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Africa et al.

- The Western democracies have displayed unprecedented solidarity in responding as one to the Russian threat.

This narrative already has been given an airing in speeches by U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Acting Deputy Secretary of State Victoria Nuland. Its target audience is the American public; nobody outside the Collective West buys it, though — whether Washington has registered that fact of diplomatic life or not.

Retroactively Scale Back the Goals & Stakes

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken looks at weapons and an underground bunker in the Kiev Oblast on Sept. 7. (State Department, Chuck Kennedy, Public domain)

- Make no further reference to regime change in Moscow, to toppling Putin, to crashing the Russian economy, to breaking the Sino-Russian partnership or to fatally weaken it.

- Speak of safeguarding the integrity of the Ukrainian state by denying that the Donbass and Crimea have been permanently severed from the “mother country.” Emphasize that your friends in Kiev are still titular, legitimate leaders of Ukraine.

- Aim for a permanent ceasefire that would freeze the two sides in existing positions, i.e. a de facto division a la Korea. The Western portion then would be admitted to NATO and the EU, and rearmed. Ignore the inconvenient truth that Russia would never accept a ceasefire on those terms.

- Maintain the economic sanctions on Russia but look the other way when needy European partners make under-the-table deals for Russian oil and LNG (mostly through intermediaries like India, Turkey and Kazakhstan) as they have been doing throughout the conflict.

- Put the spotlight on China as the mortal threat to America and the West while disparaging Russia as just its auxiliary.

- Highlight symbolic gestures like the strikes by top-of-the-line supersonic and hypersonic cruise missiles transferred from the U.S., Britain and France that can inflict damage on prominent targets in Russia itself and Crimea (with crucial technical support from American and other NATO personnel). This act is akin to rabid fans of a football team that just lost to a hated rival who puncture the tires on the bus scheduled to take them to the airport.

Cultivate Amnesia

U.S. helicopters on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Midway during the evacuation of Saigon, April 1975. (DanMS, Wikimedia Commons)

Americans have become masters in the art of memory management.

Think about the tragic shock of Vietnam. The country made a systematic effort to forget — to forget everything about Vietnam. Understandably; it was ugly — on every count. Textbooks in American history gave it little space; teachers downplayed it; television soon disregarded it as retro. Americans sought closure — we got it.

In a sense, the most noteworthy inheritance from the post-Vietnam experience is the honing of methods to photoshop history. Vietnam was a warm-up for dealing with the many unsavory episodes in the post-9/11 era. That thorough, comprehensive cleansing has made palatable presidential mendacity, sustained deceit, mind-numbing incompetence, systemic torture, censorship, the shredding of the Bill of Rights and the perverting of national public discourse — as it degenerated into a mix of propaganda and vulgar trash-talking. The “War on Terror” in all its atrocious aspects.

Cultivated amnesia is a craft enormously facilitated by two broader trends in American culture: the cult of ignorance whereby a knowledge-free mind is esteemed as the ultimate freedom; and a public ethic whereby the nation’s highest officials are given license to treat the truth as a potter treats clay so long as they say and do things that make us feel good.

So, in the U.S., the strongest collective memory of America’s wars of choice is the desirability – and ease – of forgetting them. “The show must go on” is taken as the imperative. So it will be when we look at a ruined Ukraine in the rear-view mirror.

The cultivation of amnesia as a method for dealing with painful national experiences has serious drawbacks. First, it severely restricts the opportunity to learn the lessons it offers.

In the wake of the inconclusive Korean War where the United States suffered 49,000 killed in action, the mantra in Washington was: no war on the mainland of Asia ever again.

Yet, less than a decade later the U.S. was knee-deep in the rice paddies of Vietnam where America lost 59,000 people.

After the tragic fiasco in Iraq, Washington nonetheless was gung-ho about occupying Afghanistan in a 20-year enterprise to construct a similar Western-leaning democracy out of the barrel of a gun.

Those frustrated projects did not dissuade the U.S. from intervening in Syria where it failed once again to turn an intractable, alien society into something to its liking — even though it went to such an extreme as a tacit partnership with the local Al-Qaeda subsidiary. As Kabul showed, the U.S. didn’t even take away from the Saigon denouement the lesson in how to organize an orderly evacuation.

U.S. paratroopers prepare to board an aircraft at the Hamid Karzai International Airport during the evacuation of Kabul, Aug. 30, 2021. (U.S. Army, Alexander Burnett, Public domain)

At the very least, one might have expected that a reasonable person would have come away with an acute awareness of how crucial is a fine-grain understanding of the culture, social organization, mores and philosophical outlook of the country the U.S. was committed to reconstituting. The U.S. has manifestly not assimilated that elementary truth. Witness the abysmal ignorance of all things Russian that has led the U.S. to a fatal miscalculation of every aspect of the Ukraine affair.

Next: China

Ukraine, in turn, is not cooling the ardor for confrontation with China. An audacious, and by no means a compelling, enterprise that is ensconced as the centerpiece of Washington’s official national security strategy.

Senior Washington officials openly predict the inevitability of all-out war before the end of the decade — nuclear weapons notwithstanding.

Moreover, Taiwan is cast in the same role as that played by Ukraine in the American scheme of things. So, having provoked a multi-dimensional conflict with Russia which has failed on all counts, the U.S. hastily commits itself to the nearly exact same strategy in taking on an even more formidable foe. This could be classified as what the French call a fuite en avant — an escape forward. In other words: Bring it on! We’re geared up for it.

The march to war with China defies all conventional wisdom. After all, the nation poses no military threat to U.S. security or core interests. China has no history of empire-building or conquest. China has been the source of great economic benefit via dense exchanges that serve both sides.

Therefore, what is the justification for the widespread judgment that a crossing-of-swords is inescapable? Sensible nations do not commit themselves to a possibly cataclysmic war because China, the designated No. 1 enemy, builds radar warning stations on sandy atolls in the South China Sea? Because it markets electric vehicles more cheaply? Because its advances in developing semi-conductors may outclass those of the U.S.?

Because of its treatment of an ethnic minority in western China? Because it follows the U.S. example in funding NGOs that promote a positive view of their country? Because it engages in industrial espionage just the way the United States and everybody else does? Because it wafts balloon over North America (declared benign by General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, last week)?

None of these are compelling reasons to press hard for a confrontation. The truth is far simpler — and far more disquieting. The U.S. is obsessed with China because it exists. Like K-2, that itself is a challenge for the U.S. must prove its prowess (to others, but mainly to ourselves), that it can surmount it. That is the true meaning of a perceived existential threat.

The focal shift from Russia in Europe to China in Asia is less a mechanism for coping with defeat than the pathological reaction of a country that, feeling a gnawing sense of diminishing prowess, can manage to do nothing more than try one final fling at proving to itself that it still has the right stuff — since living without that exalted sense of self is intolerable.

What is deemed heterodox, and daring, in Washington these days is to argue that it should wrap up the Ukraine affair one way or another so it might gird its loins for the truly historic contest with Beijing. The disconcerting truth that nobody of consequence in the country’s foreign policy establishment has denounced this hazardous turn toward war supports the proposition that deep emotions rather than reasoned thought are propelling the U.S. toward an avoidable, potentially catastrophic conflict.

A society represented by an entire political class that is not sobered by that prospect rightly can be judged as providing prime facie evidence of being collectively unhinged.

Amnesia may serve the purpose of sparing our political elites, and the American populace at large, the acute discomfort of acknowledging mistakes and defeat. However, that success is not matched by an analogous process of memory erasure in other places.

The U.S. was fortunate, in the case of Vietnam, that the United States’ dominant position in the world outside of the Soviet Bloc and the PRC allowed it to maintain respect, status and influence.

Things have now changed, though. The U.S. relative strength in all domains is weaker, strong centrifugal forces around the globe are producing a dispersion of power, will and outlook among other states. The BRICs phenomenon is the concrete embodiment of that reality.

Hence, the prerogatives of the United States are narrowing, its ability to shape the global system in conformity with its ideas and interests are under mounting challenge, and premiums are being placed on diplomacy of an order that seems beyond its present aptitudes.

The U.S. is confounded.

Michael Brenner is a professor of international affairs at the University of Pittsburgh. mbren@pitt.edu

https://consortiumnews.com/2023/09/21/us-cant-deal-with-defeat/

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten