Ex-mercenary claims South African group tried to spread Aids

New documentary details unit’s disturbing obsession with HIV

A South Africa-based mercenary group has been accused by one of its former members of trying to intentionally spread Aids in southern Africa in the 1980s and 1990s.

The claims are made by Alexander Jones in a documentary that premieres this weekend at the Sundance film festival. He says he spent years as an intelligence officer with the South African Institute for Maritime Research (SAIMR), three decades ago, when it was masterminding coups and other violence across Africa.

The film also explores the unexplained murder of a young SAIMR recruit in 1990, whose family believe was killed because of her work on an Aids-related project run by the group in South Africa and Mozambique.

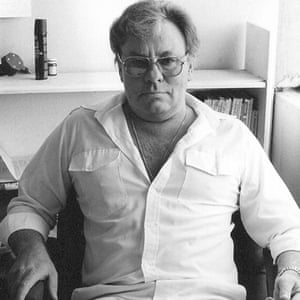

And it also claims the group’s then leader had a racist, apocalyptic obsession with HIV/Aids. Keith Maxwell wrote about a plague he hoped would decimate black populations, cement white rule, and bring back conservative religious mores, according to papers collected by the film-makers.

Maxwell had no medical qualifications but ran clinics in poor, mostly black areas around Johannesburg while claiming to be a doctor. That gave him the opportunity for sinister experimentation, Jones says in the film, Cold Case Hammarskjöld. The film-makers were investigating SAIMR because it claimed responsibility for the mysterious 1961 plane crash that killed Dag Hammarskjöld, then UN secretary general.

“What easier way to get a guinea pig than [when] you live in an apartheid system?” Jones says in the film. “Black people have got no rights, they need medical treatment. There’s a white ‘philanthropist’ coming in and saying, ‘You know, I’ll open up these clinics and I’ll treat you.’ And meantime [he is] actually the wolf in sheep’s clothing.”

A sign advertising “Dokotela [doctor] Maxwell” still hangs from the side of an office in Putfontein where locals remember a respected man with a virtual monopoly on the area’s healthcare. He offered strange treatments. including putting patients through “tubes”, which he said allowed him to see inside their bodies. He also gave “false injections”, said Ibrahim Karolia, who ran a shop across the road.

Any interest Maxwell showed in Aids in public was benevolent. Claude Newbury, an anti-abortion doctor who knew the mercenary leader, confirmed he had no medical qualifications but described a committed humanitarian. “He was against genocide and he was trying to discover a cure for HIV,” Newbury told film-makers.

A bizarre Johannesburg Sunday Times interview with teenage SAIMR “ensign” Debbie Campbell in August 1989 has a photo of a teenager with a halo of curls, taking water pollution measurements and also talking about searching for a cure for HIV/Aids. But the wholesome image has a sinister undertone. She describes being recruited out of school at 13, and it’s hard to imagine any benign interest an international mercenary group could have in signing up prepubescent girls.

Documents collected by the film-makers appear to show that Maxwell’s private views were very different from his public persona. The papers suggest a ghoulish delight in the advent of an epidemic. In one he writes: “[South Africa] may well have one man, one vote with a white majority by the year 2000. Religion in its conservative, traditional form will return. Abortion on demand, abuse of drugs, and the other excesses of the 1960s, 70s and 80s will have no place in the post-Aids world.”

The papers read like the fever dream of a man who aspired to be South Africa’s Josef Mengele. There are detailed, if sometimes garbled, accounts of how he thought the HIV virus could be isolated, propagated and used to target black Africans.

What is less clear is whether he had the expertise or funds to implement his nightmarish visions. Jones, the former SAIMR member, claims he did. “We were involved in Mozambique, spreading the Aids virus through medical conditions,” he says.

At least one other SAIMR member had apparently raised concerns about the group’s medical programmes. Dagmar Feil was a marine biologist who was recruited by her boyfriend. In 1990 she was murdered outside her home in Johannesburg; her relatives believe the killing was linked to her work on SAIMR’s Aids programme.

“My sister came to me, and she said she needed to confide in me,” her brother Karl Feil told the film-makers. “She sat with me and said she thinks they are going to kill her.” She said that three or four others in her team had already been murdered, but when asked what team, Dagmar said “she couldn’t tell me”.

“The topic of Aids research came up several times, quite loosely in conversations, I never put two and two together,” Feil says in the film. Instead Dagmar asked Karl to go with her to church, so she could “make right with God”. Weeks later she was dead.

Jones says he knew Dagmar Feil and claims her death came after a trip to Mozambique, which he describes as a base for the group’s medical experimentation. “She was recruited to do medical research,” he says. “She progressed and she became part of the inner circle for operations. She went to Mozambique to fulfil her obligations and … word got out that she was going to testify.”

Feil’s family spent years trying to find out what happened to her, but police showed little interest, her brother says. During that time, the family say another SAIMR member gave them papers believed to be Maxwell’s memoir and his account of SAIMR. They later shared these with the film-makers.

Dagmar Feil’s mother also went to South Africa’s truth and reconciliation commission several times, Karl Feil said. She asked it to investigate her daughter’s killing as part of a wider conspiracy, but was turned away.

Although the commission first revealed the existence of SAIMR to the world, the team was also overworked and had to deal with false confessions, and what the family saw as their best hope of uncovering the truth slipped away. “They would not listen to her,” Karl Feil says. “They would not debate this issue at all.”

Andreas Rocksen co-produced and Mads Brügger directed Cold Case Hammarskjöld. It was supported by DocSoc

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten