Chicago Could Blow if Laquan McDonald’s Killer Walks

My earliest memories of growing up in Chicago are steeped in racial tension and political violence: a street covered with Chicago police cars because Malcolm X was speaking under threat of assassination at a local mosque; Martin Luther King meeting a hail of rocks and bottles in a white-ethnic neighborhood on the city’s Southwest Side; and much of the city’s black West Side erupting in flames, with Mayor Richard J. Daley telling police to “shoot to kill” rioters in the wake of King’s assassination.

That was seven Chicago mayors and 11 U.S. presidents ago. In the intervening decades, Chicago has moved along with the rest of urban America into a neoliberal, post-civil rights era, in which persistent racial hypersegregation and inequality are cloaked, to a degree, by the rise of a black middle class and by the presence of black faces in high and visible places, be they among television news teams or state and federal officials.

Along the way, Chicago emerged as a global city—a prominent center of national and international finance, trade, real estate, tourism, culture and information technology. A corporate and financial growth machine steered the city past the postindustrial decline that plagued other Rust Belt cities.

Beneath the shine of a monied downtown (the Loop) and its ever-expanding zones of professional-class gentrification, however, the city remains militantly separate and unequal. Chicago is the most segregated city in the nation, with a black-white “residential dissimilarity index” of 82.5 (a rate of zero indicates complete integration and 100 means complete segregation) and a black-Latinx measure of 82.2.

The majority of the city’s black children grow up in poor neighborhoods that are 90 percent or more black. These community areas are shockingly bereft of basic opportunities, services and amenities, from job networks to good public schools, full-service grocery stores, doctors’ offices, green space and nonfast-food restaurants. They are deprived of public and private investment by a metropolitan order that grants massive tax breaks and other subsidies to rich and powerful commercial real estate developers in the more affluent, whiter parts of town.

“There’s been a huge depopulation of [blacks] south of the West Side,” Chicago anti-war and anti-racist activist Andy Thayer tells me. The city’s neoliberal mayor, Rahm Emanuel, has “made black neighborhoods unlivable,” Thayer says, by “starving them of public resources, closing public schools and mental health clinics.”

The results are not pretty. A University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) report last year found racial and ethnic inequality in the city so “pervasive, persistent, and consequential” as to make life for white, black and Latino Chicagoans “a tale of three cities.” Combing through census and other data, the UIC’s Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy found that Chicago has “fail[ed] to address the long-term consequences of decades of formal and widespread private and public discrimination along with continuing forms of entrenched … institutional and interpersonal forms of discrimination.” Among its findings:

● At 18 percent, Chicago’s black unemployment rate is more than four times the city’s white unemployment rate (4 percent) and double the Latinx rate (9 percent).

● Nearly a third of Chicago’s black families, but less than a tenth of the city’s white families, live below the federal government’s notoriously inadequate poverty line.

● In 1960, the typical white Chicago family earned 1.6 times more than the typical black family. Today, the typical white family earns 2.2 times more than typical black families.

● Black and Latino households experience rampant mortgage interest rate and payment schedule discrimination.

● Home foreclosures are drastically overconcentrated in black and Latino communities, with as much as 25 percent of the housing stock abandoned in some all-black South Side neighborhoods.

● Nine out of 10 black and Latino students attend schools where 75 percent or more of the student population is eligible for free or reduced-cost lunches.

● Black students are suspended at four times the rate of Latinos and 23 times the rate of whites.

● While crime is down in Chicago, incarceration rates have skyrocketed due to policy shifts, including aggressive policing strategies and mandatory-minimum sentencing. Illinois’ disproportionately (60 percent) black prisons are operating at 150 percent of maximum capacity, fueled largely by racially discriminatory policing and sentencing practices.

● Chicagoans of color are subject to far more police surveillance and intervention than whites. “Although blacks and Latinos have their vehicle searched at four times the rate of their white counterparts,” UIC researchers find, “they are half as likely to be in possession of illegal contraband or a controlled substance.”

● Blacks experience heart disease, stroke, infant mortality, low birth weight and mortality in general at far higher rates than whites.

Violence looms around every corner in much of black Chicago, and not just the violence of inner-city gangs. The “biggest gang of all,” many black residents will tell you, is the Chicago Police Department (CPD), a leading enforcer of the city’s durable and interrelated barriers of race, class and place. In a report on the CPD by the Department of Justice in the final days of the Obama administration, federal investigators painted an ugly picture of a major metropolitan gendarme force out of control in black and Latino neighborhoods:

Chicago Police Department (CPD) officers engage in a pattern or practice of using force, including deadly force, that is unreasonable. … Officers engage in … unnecessary foot pursuits … [that] too often end with officers unreasonably shooting someone—including unarmed individuals. … Officers shoot at vehicles without justification. … Officers exhibit poor discipline when discharging their weapons …[and often] fail … to await backup when they safely could and should. … CPD officers shot at suspects who presented no immediate threat … and us[e] unreasonable retaliatory force and unreasonable force against children. …CPD’s pattern or practice of unreasonable force … fall[s] heaviest on the predominantly black and Latino neighborhoods on the South and West Sides of Chicago, which are also experiencing higher crime. … CPD uses force almost ten times more often against blacks than against whites.

Chicago’s Independent Police Review Authority received no less than 10,000 excessive-force complaints between 2008 and 2015, resulting in the dismissal of just four officers.

One of the many black people killed by Chicago police in recent years was Harith Augustus. A respected barber and dedicated father of a little girl, Augustus was gunned down by a white officer who shot him at least five times in the back as he ran away. The police initiated the incident by trying to apprehend him as he walked peacefully down a street in the black South Side neighborhood of South Shore.

The department absurdly justified the shooting by claiming that Augustus, 37, was “exhibiting the characteristics of an armed person.”

As the officer who killed Augustus was whisked away in a patrol car, protesters gathered at the scene, charging “murder.” A melee ensued between black community residents and 80 to 100 officers. By Chicago Sun-Times reporter Nader Issa’s account, “Dozens of officers were called to help control a tense scene as more than 100 people crowded around, chanting at police, ‘Who do you serve? Who do you protect?’ ”

Could the city explode in racial violence again, on a larger, 1968-level, in response to police violence and repression?

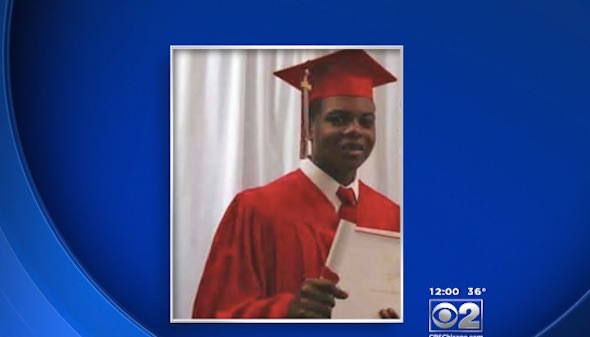

Yes, it could, thanks to how the case of Laquan McDonald and Jason Van Dyke, the Chicago police officer who killed him four years ago, is being handled by the authorities. Van Dyke is currently on trial for the shooting.

You can see the Oct. 20, 2014, incident online. The police dashcam video of the killing has been viewed millions of times since the public demanded its release in late 2015.

You watch the young victim walking away from his killer. You see 17-year-old Laquan’s body lying on the ground, curled up in a fetal position and jolted as Van Dyke pumps multiple bullets into him. Van Dyke drilled McDonald 16 times in 15 seconds, with the suspect on the ground for 13 of those seconds.

What sets Van Dyke’s shooting apart from the broad run of incidents in which black people are killed by police is its palpable and widely viewed heinousness, to say nothing of the outrage it elicited in Chicago’s black community and around the world.

The Van Dyke-McDonald shooting tape is certainly the most inflammatory and widely observed film evidence of racist police brutality to make its way into the mass media since the video that showed a large group Los Angeles police officers beating Rodney King nearly three decades ago.

Chicago was roiled by protests that became national-headline news after the video came out in late 2015. But for those protests, Van Dyke would never have been charged with murder.

Nobody grasped the historic nature of the shooting when it occurred. “The McDonald killing,” Thayer recalls, “was just another blip.” But for an inside tip from an anonymous police officer to prominent Chicago activist Jamie Kalven, nobody would have learned about the horrific nature of Laquan’s shooting or the existence of the videotape. And but for the dedicated Freedom of Information activism of an Uber-driving, independent journalist named Brandon Smith, the tape would never been released. The city produced the tape only because it was legally compelled to by a county judge ruling in a lawsuit filed by Smith.

It wasn’t the tape alone that brought thousands into the streets and raised demands for Emanuel’s exit from City Hall. Emanuel added fuel to the fire by keeping the tape under wraps because he feared it would deep-six his chance of winning the black votes he needed after years of alienating the community by closing dozens of public schools in their neighborhoods and stonewalling on racist police abuse and misconduct (including the operation of a “black site” detention center on the city’s West Side).

Emanuel, it was ultimately revealed, had offered McDonald’s family a $5 million settlement to keep it quiet prior to the mayor’s re-election bid in the spring of 2015.

Emanuel claimed that he’d never seen the video prior to its release on Nov. 24, 2015—a preposterous story, given his approval of the settlement prior to the election.

Van Dyke, Laquan’s killer, was allowed to stay on the force, at full pay, for 13 months after conducting an extrajudicial killing that was clearly captured on tape.

Journalists later discovered that other Chicago officers on the scene threatened eyewitnesses with arrest and deleted more than an hour of footage from a fast-food restaurant near the shooting site. Numerous Chicago police officers who witnessed the killing protected Van Dyke (in accordance with “blue code”) by making abjectly counterfeit reports claiming that McDonald posed an imminent threat to his killer.

In a meeting with black ministers before the video’s release, Emanuel arrogantly warned them that he would withhold money for jobs programs in black neighborhoods if civil unrest ensued.

Emanuel has recently announced that he will not run for a third term in 2019, recognizing that his handling of the killing likely doomed him among black voters.

Emmanuel, the school privatization champion, “can’t even visit one of his inner-city charter schools,” Thayer reports, “without the kids all chanting ‘Sixteen Shots and a Cover-Up! Sixteen Shots and a Cover-Up!’ ”

Both the trial and its runup have been disquieting. Chicago media helped Van Dyke’s lawyer try to pollute the jury pool prior to jury selection by publishing interviews in which Van Dyke said, “You don’t ever want to shoot your gun. I never would have fired my gun if I didn’t think my life was in jeopardy or another citizen’s life was.”

A local television station broadcast a pre-jury-selection interview in which Van Dyke’s wife tearfully told viewers that she is “petrified” over the prospect of her husband going to prison for “doing the job for which he was trained.”

Van Dyke’s defense attorney, Daniel Herbert, failed to get the trial moved out of Chicago’s Cook County but succeeded in securing a 12-person jury composed of just one black person, seven white people and a Latina who is applying to be a Chicago Police Department officer. Chicago is 32.9 percent black.

At trial, the opening statement by Van Dyke’s attorney was equally provocative. As the Chicago Tribune reported, “Herbert said Van Dyke paused to reassess after firing 14 of the 16 shots. He didn’t know if they were lethal gunshots. He didn’t know if Laquan McDonald had the ability to get back up and attack him,” he said. ‘McDonald holds on to his knife the whole time he’s on the ground. Despite being shot 14 times, he starts making movements.’ ”

In what bizarre universe was McDonald a threat to the gun-wielding Van Dyke as the bullet-riddled teenager lay dying?

On the second day of the trial, Herbert rolled out Van Dyke’s former partner, Officer Joe Walsh, who claimed that McDonald “raised [his] knife to shoulder height and swung it moments before Van Dyke opened fire.” The video shows Walsh’s testimony to be a bald-faced lie.

The defense has brought out an expert witness to perversely claim that the large number of shots Van Dyke pumped into Laquan didn’t matter because the 17-year-old was killed by an early bullet; presented a Cook County detention officer with stories of McDonald’s past “agitation,” as though that were justification for his killing; had a Chicago Police Department officer testify that McDonald “looked deranged” before he was killed; and presented evidence that the victim had taken PCP, a drug that can give users a feeling of “omnipotence.”

On Tuesday, Van Dyke’s attorney put him on the stand. “His [Laquan’s] face had no expression, his eyes were just bugging out of his head,” Van Dyke said. “He had these huge white eyes, just staring right through me,” he told the jury.

“Huge white eyes” that were “bugging out of his head”? At best, Van Dyke’s language is highly racialized. At worst, it’s overtly racist.

The irony is that Van Dyke, not McDonald, was the attacker, wielding a deadly, rapid-fire pistol. What kind of expression did Van Dyke have on his face while he launched a fusillade of bullets into the stricken youth?

A veteran black activist tells me he’s heard that “Van Dyke will be thrown to the mob” as “a kind of token” to pacify the city’s black population and take the heat off a racist police state.

Closing arguments are due no later than Friday, and a verdict could be handed down as early as next week. A rally is planned outside City Hall one hour after the decision, whatever its outcome.

Could Chicago explode if Van Dyke walks? Every activist and observer I’ve spoken to here says the chances of mass protest and disturbances are high, because the city’s black neighborhoods are full of young people fed up with brutal and racist policing and the savage inequality and segregation that it enforces.

That Emanuel, widely hated in the black community, is leaving could temper things. At the same time the fact that “Mayor Rhambo”—a great lover of the militarized police state—no longer has to worry about losing black votes could help entice him to order a harsh crackdown on protests.

My prediction: guilty on second- but not first-degree murder. If it’s “not guilty,” there will be hell to pay.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten