Harvard’s Inescapable History of Race Hate

There is not a more coveted degree in America than that which is conferred by Harvard University. The Cambridge center of traditional American intellectualism can lay claim to having stamped a goodly number of government and industry leaders with its crimson imprimatur. A Black person wearing a Harvard brand has always earned the special attention of the masses, mostly because of the white custom of unilaterally elevating its Black matriculants to race leadership. So, when Claudine Gay—a Black woman—became Harvard’s 30th president, Black academia counted it as a major advancement. But once President Gay tried to make that Cambridge campus safe for open actual debate on the issue of Palestine, her tenure became the shortest on record—exactly six months and a day.

So, what is Harvard University to Black folks? Maybe it is time to examine the legacy of this institution that the Rev. Adam Clayton Powell confidently asserted had “ruined more negroes than bad whiskey.” A brief racial history of America’s intellectual Vatican puts its special role, and Powell’s biting assessment, in proper context.

Harvard College was founded in 1636 (just six years after the settlement of Boston) with the intent of academically assisting the clergy in their attempts to brainwash the Massachusetts Indians into accepting white European customs and religious beliefs. In this they were wholly unsuccessful, having only graduated one Indian, who died just a year later. Once conversion failed, the ol’ Pilgrim/Puritan standby of massacres and mayhem was employed, and the Red man was no longer welcome at Harvard. Thus, in 1698 Harvard tore down its “Indian College” and used the bricks to construct the new Stoughton College—named for the family of the man who has been “credited” with the annihilation of the Pequot Indians in 1637.

Quiet as it’s kept, the slave trade was the primary economic force in the development of Boston’s elite, and most of that class were trained at Harvard. Puritan minister and president of Harvard (1685–1701) Increase Mather held African slaves. Benjamin Wadsworth, president from 1725–1737, was a member of one of the leading slaveholding families in New England. “Servants are very Wicked,” he once wrote, “when they are LAZY and IDLE in their Master’s Service. The Slothful Servant is justly called Wicked…” In 1756, the First Parish Church at Cambridge was made off-limits to Blacks when Harvard officials objected to their sitting in the gallery. In 1773 Harvard hosted a debate in which Blacks were defined as “a conglomerate of child, idiot and madman.” Many of the early ship-owning slave traders of New England sent their children to Harvard, as did many of the Southern plantation owners. The grand wizard of the Massachusetts Ku Klux Klan graduated from Harvard in 1853.

One of the most viciously anti-Black newspapers in Boston history, the Courier, was run by a Harvard grad George Lunt. Lunt hated both abolitionism and abolitionists and swiftly gained an editorial reputation for being a defender of slavery and its attendant evils. He was convinced that “the holding of negroes in slavery, in this country or any other, is a question of circumstances, and not of morality at all.” After all, “The negroes were perfectly happy in their condition of slavery in the South. They were not only happy but proud of it.” And if they were let go it would prove to be an “intolerable” “burden,” the result being “helpless, irresponsible creatures…incapable by nature, of the independent action demanded by a civilized community.”

It only gets worse from there. A host of paragons of race hate acquired their intellectual bearings at this Cambridge center of white supremacy, including many icons of American history. John Adams, Samuel Adams, Josiah Quincy, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Theodore Roosevelt, to name a few, have proudly ascended to the upper echelon of America’s racial villainy. John Adams “shuddered at the doctrine” of racial equality and spoke in Hitlerian terms of “quieting the Indians forever.” Samuel Adams and Josiah Quincy both enslaved Black Africans. Divinity school graduate Ralph Waldo Emerson asserted matter-of-factly that “it is better to hold the negro one inch below water than one inch above it.” Theodore Rooseveltvoiced the common Harvard creed that Blacks were backward savages who needed strong white rule to bring them into civilization. The Africans, this Harvard-trained American president believed, were “ape-like, naked savages, who dwell in the woods and prey on creatures not much wilder or lower than themselves.”

Harvard, a pillar of the Brahmin establishment, “did its best to stifle anti-slavery [legislation].” When expelled German scholar Charles Follen sought refuge in America, he found it on the Harvard faculty. But when he became an abolitionist in 1833, he was immediately fired. When Harvard graduate Charles Sumner criticized slavery in a speech to the student body in 1848, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow recorded the reaction: “the shouts and hisses and the vulgar interruptions grated on my ears.” Two of the college’s honorable presidents, Jared Sparks and Cornelius Felton, were strong supporters of the notorious Fugitive Slave Bill, which aligned the northern “free states” with the Southern slave-owners in apprehending runaway Black slaves. When a Southern slaveholder came up to a Boston court to use the fugitive slave law to reclaim “his slave” Anthony Burns, Harvard students acted as the slaveholder’s bodyguards.

Distinguished Harvard graduate Lemuel Shaw was considered to be the most influential state judge in American history. Shaw considered Blacks who escaped from chattel slavery to be “fugitives from labor” and ordered their immediate return. When two Black women were arrested in 1836 as escaped slaves, Shaw allowed the slave catchers to correct their faulty warrant so that they could re-arrest them right in his courtroom. The Blacks who came to court refused to stand by and allow for this outrage and attempted to rescue the women. Shaw himself tried to stop them before he was knocked to the floor during the successful escape.

As chief justice, Shaw delivered the unanimous opinion of the Massachusetts Supreme Court which upheld the legality of school segregation, providing the basis for the doctrine of “separate but equal”—America’s official racial policy until 1954. Between 1872 and 1949 at least eleven state courts cited Shaw’s opinion to justify their own state’s segregationist policies. (In 1956, when Virginia Senator Robert Byrd read his infamous “Defiance: The Southern Manifesto” he cited Shaw’s opinion to buttress his last stand against the Supreme Court’s desegregation order.)

The many well-to-do Harvard students from Southern plantation families did not have to long for the amenities of their beloved slavocracy: upon their arrival at the University each cracker was given a Black servant they euphemistically called a “scout.” All the while, Blacks served Harvard’s white faculty and enrollees as janitors, custodians, and waiters. The first record of these “scouts” at Harvard is noted by Samuel F. Batchelder, in Bits of Harvard History, as he contemptuously recounts the traumas of Harvard’s unpaid, overworked “ebony faced” “college coons” and “darkeys,” a “tribe” of “dusky child[ren] of nature” with “rolling white eyeballs.”

Nonetheless, Blacks were always seeking to “better” themselves and attempted to break through Harvard’s customary racial wickedness. When three Black men attended lectures at the Medical School in 1850, groups of white students protested their presence and prevailed upon the faculty to expel them. Harvard president Charles Eliot (term 1869–1909) stated his belief in separate educational facilities for Blacks and whites and suggested that Harvard may implement such a policy. He maintained—quite accurately—that the white man in the North is no less averse to the mingling of races than his Southern counterpart.

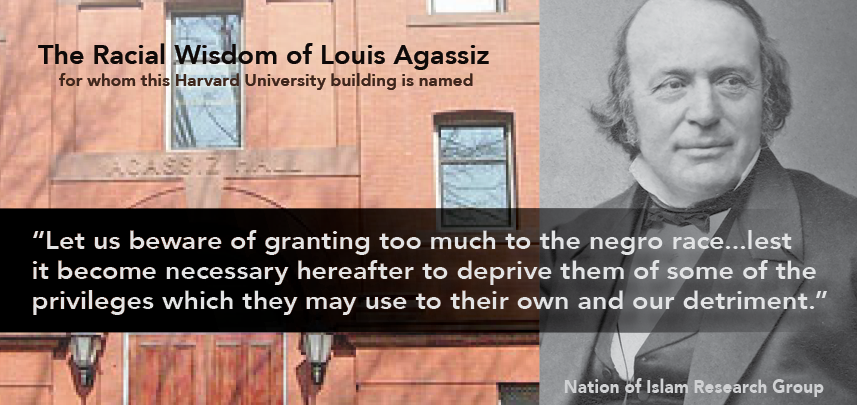

Race hater Louis Agassiz (1807–1873), the dean of the Nazi-adopted philosophy of scientific racism, warned fellow whites: “Let us beware of granting too much to the negro race…lest it become necessary hereafter to deprive them of some of the privileges which they may use to their own and our detriment.” Agassiz found his views of the Black man warmly received and echoed by Harvard deans Henry Eustis, who considered Blacks “little above beasts,” and Nathaniel Shaler, who believed Blacks “unfit for an independent place in a civilized state.” According to its website, the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University was founded by Agassiz, and though he died a century and a half ago it took the museum until 2022 to “soundly reject” his racial views. Up until then it had maintained that Agassiz was “a great systematist, paleontologist and renowned teacher of natural history.” It took a lawsuit filed in 2019 by a descendant of one of Agassiz’s Black victims, Tamara Lanier, to force the recent tepid response from Harvard.

The South’s greatest crime, according to Theodore Roosevelt, was not instituting slavery but bringing so many Africans within America’s borders, creating an insoluble problem for whites. There is one problem Black slaves did resolve for the Roosevelts: the president’s mother, Mittie, sold four of her own slaves in 1855 just to pay for her wedding to Teddy’s father. Roosevelt opined extensively on the utter inferiority of the Black race and the responsibilities of over-lordship that were assigned to the white man. His presidency (1901–1909) saw rampant lynchings and Jim Crow policies but offered only weak condemnation and no executive action.

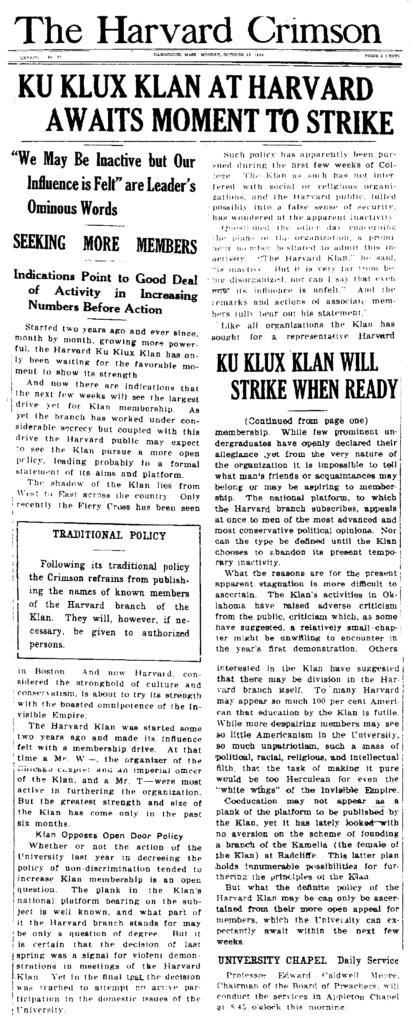

In 1922–23, President A. Lawrence Lowell barred Blacks from living in the freshman dormitories saying, “We have not thought it possible to compel men of different races to reside together.” Around that time, Harvard’s venerable newspaper, the Crimson, excitedly announced the presence of the school’s very own Ku Klux Klan chapter! Without a trace of indignation, it trumpeted the KKK’s campus membership drive. The paper even promised to respect the secret identities of the KKK leaders, and announced the possibility of the establishment of the branch of the KKK called Kamelia, the female KKK, at Radcliffe, the women’s school founded by Louis Agassiz’s wife. By 1960 Harvard was writing letters to white students asking if they had problems with being assigned a Black roommate. (Black students received no such “courtesy.”)

After some loud but ineffectual liberal ’70s campus activism Harvard pretended to reform itself, but by the 1980s Bell Curve authors Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein—both Harvard alums—successfully restored Harvard’s white-hooded intellectual tradition, asserting that IQ is genetically determined.

With every successive generation, since its founding four centuries ago, Harvard’s public-relations specialists successfully cleanse it of its truly odious racial legacy. The firing of Dr. Claudine Gay has only exposed Harvard for what it always was and forever intends to be.

RSS

RSS

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten