Site Navigation

THE WAR PHOTO NO ONE WOULD PUBLISH

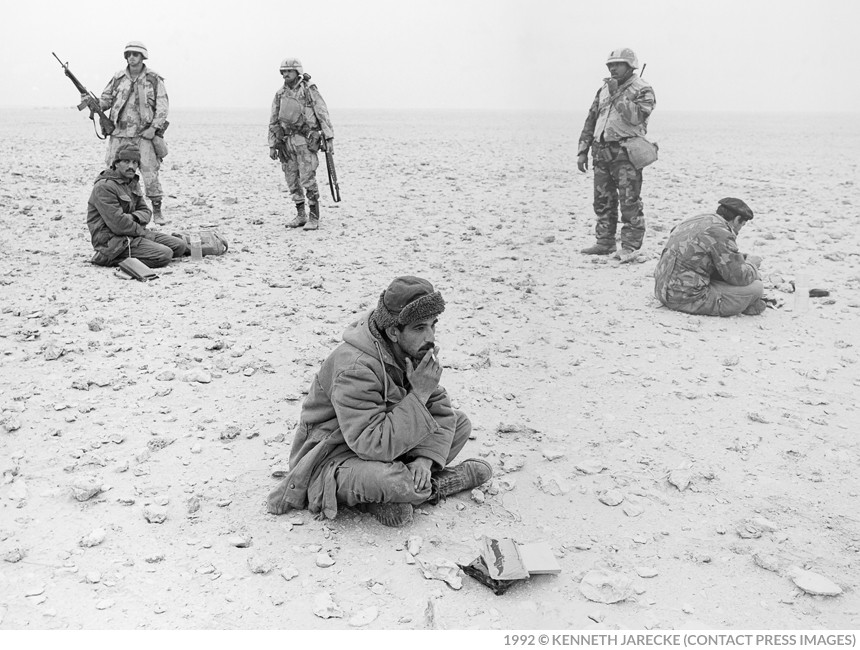

When Kenneth Jarecke photographed an Iraqi man burned alive, he thought it would change the way Americans saw the Gulf War. But the media wouldn’t run the picture.

The Iraqi soldier died attempting to pull himself up over the dashboard of his truck. The flames engulfed his vehicle and incinerated his body, turning him to dusty ash and blackened bone. In a photograph taken soon afterward, the soldier’s hand reaches out of the shattered windshield, which frames his face and chest. The colors and textures of his hand and shoulders look like those of the scorched and rusted metal around him. Fire has destroyed most of his features, leaving behind a skeletal face, fixed in a final rictus. He stares without eyes.

On February 28, 1991, Kenneth Jarecke stood in front of the charred man, parked amid the carbonized bodies of his fellow soldiers, and photographed him. At one point, before he died this dramatic mid-retreat death, the soldier had had a name. He’d fought in Saddam Hussein’s army and had a rank and an assignment and a unit. He might have been devoted to the dictator who sent him to occupy Kuwait and fight the Americans. Or he might have been an unlucky young man with no prospects, recruited off the streets of Baghdad.

Jarecke took the picture just before a cease-fire officially ended Operation Desert Storm—the U.S.-led military action that drove Saddam Hussein and his troops out of Kuwait, which they had annexed and occupied the previous August. The image, and its anonymous subject, might have come to symbolize the Gulf War. Instead, it went unpublished in the United States, not because of military obstruction but because of editorial choices.

It’s hard to calculate the consequences of a photograph’s absence. But sanitized images of warfare, The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf argues, make it “easier … to accept bloodless language” such as 1991 references to “surgical strikes” or modern-day terminology like “kinetic warfare.” The Vietnam War, in contrast, was notable for its catalog of chilling and iconic war photography. Some images, such as Ron Haeberle’s pictures of the My Lai massacre, were initially kept from the public, but other violent images—Nick Ut’s scene of child napalm victims and Eddie Adams’s photo of a Vietcong man’s execution—won Pulitzer Prizes and had a tremendous impact on the outcome of the war.

Not every gruesome photo reveals an important truth about conflict and combat. Last month, The New York Times decided—for valid ethical reasons—to remove images of dead passengers from an online story about Flight MH17 in Ukraine and replace them with photos of mechanical wreckage. Sometimes though, omitting an image means shielding the public from the messy, imprecise consequences of a war—making the coverage incomplete, and even deceptive.

In the case of the charred Iraqi soldier, the hypnotizing and awful photograph ran against the popular myth of the Gulf War as a “video-game war”—a conflict made humane through precision bombing and night-vision equipment. By deciding not to publish it, Timemagazine and the Associated Press denied the public the opportunity to confront this unknown enemy and consider his excruciating final moments.

The image was not entirely lost. The Observer in the United Kingdom and Libération in France both published it after the American media refused. Many months later, the photo also appeared in American Photo, where it stoked some controversy, but came too late to have a significant impact. All of this surprised the photographer, who had assumed the media would be only too happy to challenge the popular narrative of a clean, uncomplicated war. “When you have an image that disproves that myth,” he says today, “then you think it’s going to be widely published.”

“Let me say up front that I don’t like the press,” one Air Force officer declared, starting a January 1991 press briefing on a blunt note. The military’s bitterness toward the media was in no small part a legacy of the Vietnam coverage decades before. By the time the Gulf War started, the Pentagon had developed access policies that drew on press restrictions used in the U.S. wars in Grenada and Panama in the 1980s. Under this so-called pool system, the military grouped print, TV, and radio reporters together with cameramen and photojournalists and sent these small teams on orchestrated press junkets, supervised by public-affairs officers (PAOs) who kept a close watch on their charges.

By the time Operation Desert Storm began in mid-January 1991, Kenneth Jarecke had decided he no longer wanted to be a combat photographer—a profession, he says, that “dominates your life.” But after Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, Jarecke developed a low opinion of the photojournalism coming out of Desert Shield, the prewar operation to build up troops and equipment in the Gulf. “It was one picture after another of a sunset with camels and a tank,” he says. War was approaching, and Jarecke says he saw a clear need for a different kind of coverage. He felt he could fill that void.

After the UN’s January 15, 1991, deadline for Iraq’s withdrawal from Kuwait came and went, Jarecke, now certain he should go, persuaded Time magazine to send him to Saudi Arabia. He packed up his cameras and shipped out from Andrews Air Force Base on January 17—the first day of the aerial bombing campaign against Iraq.

Out in the field with the troops, Jarecke recalls, “anybody could challenge you,” however absurdly and without reason. He remembers straying 30 feet away from his PAO and having a soldier bark at him, “What are you doing?” Jarecke retorted, “What do you mean what am I doing?”

Recounting the scene two decades later, Jarecke still sounds exasperated. “Some first lieutenant telling me, you know, where I’m gonna stand. In the middle of the desert.”

As the war picked up in early February, PAOs accompanied Jarecke and several other journalists as they attached to the Army XVIII Airborne Corps and spent two weeks at the Saudi-Iraqi border doing next to nothing. That didn’t mean nothing was happening—just that they lacked access to the action.

During the same period, the military photojournalist Lee Corkran was embedding with the U.S. Air Force’s 614th Tactical Fighter Squadron in Doha, Qatar, and capturing their aerial bombing campaigns. He was there to take pictures for the Pentagon to use as it saw fit—not primarily for media use. In his images, pilots look over their shoulders to check on other planes. Bombs hang off the jets’ wings, their sharp-edged darkness contrasting with the soft colors of the clouds and desert below. In the distance, the curvature of the earth is visible. On missions, Corkran’s plane would often flip upside down at high speed as the pilots dodged missiles, leaving silvery streaks in the sky. Gravitational forces multiplied the weight of his cameras—so much so that if he had ever needed to eject from the plane, his equipment could have snapped his neck. This was the air war that composed most of the combat mission in the Gulf that winter.

The scenes Corkran witnessed weren’t just off-limits to Jarecke; they were also invisible to viewers in the United States, despite the rise of 24-hour reporting during the conflict. Gulf War television coverage, as Ken Burns wrote at the time, felt cinematic and often sensational, with “distracting theatrics” and “pounding new theme music,” as if “the war itself might be a wholly owned subsidiary of television.”

Some of the most widely seen images of the air war were shot not by photographers, but rather by unmanned cameras attached to planes and laser-guided bombs. Grainy shots and video footage of the roofs of targeted buildings, moments before impact, became a visual signature of a war that was deeply associated with phrases such as “smart bombs” and “surgical strike.” The images were taken at an altitude that erased the human presence on the ground. They were black-and-white shots, some with bluish or greenish casts. One from February 1991, published in the photo book In The Eye of Desert Storm by the now-defunct Sygma photo agency, showed a bridge that was being used as an Iraqi supply route. In another, black plumes of smoke from French bombs blanketed an Iraqi Republican Guard base like ink blots. None of them looked especially violent.

In late February, during the war’s final hours, Jarecke and the rest of his press pool drove across the desert, each of them taking turns behind the wheel. They had been awake for several days straight. “We had no idea where we were. We were in a convoy,” Jarecke recalls. He dozed off.

When he woke up, they had parked and the sun was about to rise. It was almost 6 o’clock in the morning. The group received word that a cease-fire was a few hours away, and Jarecke remembers another member of his pool cajoling the press officer into abandoning the convoy and heading toward Kuwait City.

The group figured they were in southern Iraq, somewhere in the desert about 70 miles away from Kuwait City. They began driving toward Kuwait, hitting Highway 8 and stopping to take pictures and record video footage. They came upon a jarring scene: burned-out Iraqi military convoys and incinerated corpses. Jarecke sat in the truck, alone with Patrick Hermanson, a public-affairs officer. He moved to get out of the vehicle with his cameras.

Hermanson found the idea of photographing the scene distasteful. When I asked him about the conversation, he recalled asking Jarecke, “What do you need to take a picture of that for?” Implicit in his question was a judgment: There was something dishonorable about photographing the dead.

“I’m not interested in it either,” Jarecke recalls replying. He told the officer that he didn’t want his mother to see his name next to photographs of corpses. “But if I don’t take pictures like these, people like my mom will think war is what they see in movies.” As Hermanson remembers, Jarecke added, “It’s what I came here to do. It’s what I have to do.”

“He let me go,” Jarecke recounts. “He didn’t try to stop me. He could have stopped me because it was technically not allowed under the rules of the pool. But he didn’t stop me and I walked over there.”

More than two decades later, Hermanson notes that Jarecke’s resulting picture was “pretty special.” He doesn’t need to see the photograph to resurrect the scene in his mind. “It’s seared into my memory,” he says, “as if it happened yesterday.”

The incinerated man stared back at Jarecke through the camera’s viewfinder, his blackened arm reaching over the edge of the truck’s windshield. Jarecke recalls that he could “see clearly how precious life was to this guy, because he was fighting for it. He was fighting to save his life to the very end, till he was completely burned up. He was trying to get out of that truck.”

Jarecke wrote later that year in American Photo magazine that he “wasn’t thinking at all about what was there; if I had thought about how horrific the guy looked, I wouldn’t have been able to make the picture.” Instead, he maintained his emotional remove by attending to the more prosaic and technical elements of photography. He kept himself steady; he concentrated on the focus. The sun shone in through the rear of the destroyed truck and backlit his subject. Another burned body lay directly in front of the vehicle, blocking a close-up shot, so Jarecke used the full 200mm zoom lens on his Canon EOS-1.

In his other shots of the same scene, it is apparent that the soldier could never have survived, even if he had pulled himself up out of the driver’s seat and through the window. The desert sand around the truck is scorched. Bodies are piled behind the vehicle, indistinguishable from one another. A lone, burned man lies face down in front of the truck, everything incinerated except the soles of his bare feet. In another photograph, a man lies spread-eagle on the sand, his body burned to the point of disintegration, but his face mostly intact and oddly serene. A dress shoe lies next to his body.

The group continued on across the desert, passing through more stretches of highway littered with the same fire-ravaged bodies and vehicles. Jarecke and his pool were possibly the first members of the Western media to come across these scenes, which appeared along what eventually became known as the Highway of Death, sometimes referred to as the Road to Hell.

The retreating Iraqi soldiers had been trapped. They were frozen in a traffic jam, blocked off by the Americans, by Mutla Ridge, by a minefield. Some fled on foot; the rest were strafed by American planes that swooped overhead, passing again and again to destroy all the vehicles. Milk vans, fire trucks, limousines, and one bulldozer appeared in the wreckage alongside armored cars and trucks, and T-55 and T-72 tanks. Most vehicles held fully loaded, but rusting, Kalashnikov variants. According to descriptions from reporters like The New York Times’ R. W. Apple and The Observer’s Colin Smith, amid the plastic mines, grenades, ammunition, and gas masks, a quadruple-barreled antiaircraft gun stood crewless and still pointing skyward. Personal items, like a photograph of a child’s birthday party and broken crayons, littered the ground beside weapons and body parts. The body count never seems to have been determined, although the BBC puts it in the “thousands.”

“In one truck,” wrote Colin Smith in a March 3 dispatch for The Observer, “the radio had been knocked out of the dashboard but was still wired up and faintly picking up some plaintive Arabic air which sounded so utterly forlorn I thought at first it must be a cry for help.”

Following the February 28 cease-fire that ended Desert Storm, Jarecke’s film roll with the image of the incinerated soldier reached the Joint Information Bureau in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, where the military coordinated and corralled the press, and where pool editors received and filed stories and photographs. At that point, with the operation over, the photograph would not have needed to pass through a security screening, says Maryanne Golon, who was the on-site photo editor for Time in Saudi Arabia and is now the director of photography for The Washington Post. Despite the obviously shocking content, she tells me she reacted like an editor in work mode. She selected it, without debate or controversy among the pool editors, to be scanned and transmitted. The image made its way back to the editors’ offices in New York City.

Jarecke also made his way from Saudi Arabia to New York. Passing through Heathrow Airport on a layover, he bought a copy of the March 3 edition of The Observer. He opened it to find his photograph on page 9, printed at the top across eight columns under the heading “The Real Face of War.”

That weekend in March, when The Observer’s editors made the final decision to print the image, every magazine in North America made the opposite choice. Jarecke’s photograph did not even appear on the desks of most U.S. newspaper editors (the exception being The New York Times, which had a photo wire service subscription but nonetheless declined to publish the image). The photograph was entirely absent from American media until far past the time when it was relevant to ground reporting from Iraq and Kuwait. Golon says she wasn’t surprised by this, even though she’d chosen to transmit it to the American press. “I didn’t think there was any chance they’d publish it,” she says.

Apart from The Observer, the only major news outlet to run the Iraqi soldier’s photograph at the time was the Parisian news daily Libération, which ran it on March 4. Both newspapers refrained from putting the image on the front page, though they ran it prominently inside. But Aidan Sullivan, the pictures editor for the British Sunday Times, told the British Journal of Photography on March 14 that he had opted instead for a wide shot of the carnage: a desert highway littered with rubble. He challenged The Observer: “We would have thought our readers could work out that a lot of people had died in those vehicles. Do you have to show it to them?”

“There were 1,400 [Iraqi soldiers] in that convoy, and every picture transmitted until that one came, two days after the event, was of debris, bits of equipment,” Tony McGrath, The Observer’s pictures editor, was quoted as saying in the same article. “No human involvement in it at all; it could have been a scrap yard. That was some dreadful censorship.”

The media took it upon themselves to “do what the military censorship did not do,” says Robert Pledge, the head of the Contact Press Images photojournalism agency that has represented Jarecke since the 1980s. The night they received the image, Pledge tells me, editors at the Associated Press’s New York City offices pulled the photo entirely from the wire service, keeping it off the desks of virtually all of America’s newspaper editors. It is unknown precisely how, why, or by whom the AP’s decision was handed down.

Vincent Alabiso, who at the time was the executive photo editor for the AP, later distanced himself from the wire service’s decision. In 2003, he admitted to American Journalism Review that the photograph ought to have gone out on the wire and argued that such a photo would today.

Yet the AP’s reaction was repeated at Time and Life. Both magazines briefly considered the photo, unofficially referred to as “Crispy,” for publication. The photo departments even drew up layout plans. Time, which had sent Jarecke to the Gulf in the first place, planned for the image to accompany a story about the Highway of Death.

“We fought like crazy to get our editors to let us publish that picture,” the former photo director Michele Stephenson tells me. As she recalls, Henry Muller, the managing editor, told her, “Time is a family magazine.” And the image was, when it came down to it, just too disturbing for the outlet to publish. It was, to her recollection, the only instance during the Gulf War where the photo department fought but failed to get an image into print.

James Gaines, the managing editor of Life, took responsibility for the ultimate decision not to run Jarecke’s image in his own magazine’s pages, despite the photo director Peter Howe’s push to give it a double-page spread. “We thought that this was the stuff of nightmares,” Gaines told Ian Buchanan of the British Journal of Photography in March 1991. “We have a fairly substantial number of children who read Life magazine,” he added. Even so, the photograph was published later that month in one of Life’s special issues devoted to the Gulf War—not typical reading material for the elementary-school set.

Stella Kramer, who worked as a freelance photo editor for Life on four special-edition issues on the Gulf War, tells me that the decision to not publish Jarecke’s photo was less about protecting readers than preserving the dominant narrative of the good, clean war. Flipping through 23-year-old issues, Kramer expresses clear distaste at the editorial quality of what she helped to create. The magazines “were very sanitized,” she says. “So that’s why these issues are all basically just propaganda.” She points out the picture on the cover of the February 25 issue: a young blond boy dwarfed by the American flag he’s holding. “As far as Americans were concerned,” she remarks, “nobody ever died.”

“If pictures tell stories,” Lee Corkran tells me, “the story should have a point. So if the point is the utter annihilation of people who were in retreat and all the charred bodies … if that’s your point, then that’s true. And so be it. I mean, war is ugly. It’s hideous.” To Corkran, who was awarded the Bronze Star for his Gulf War combat photography, pictures like Jarecke’s tell important stories about the effects of American and allied airpower. Even Patrick Hermanson, the public-affairs officer who originally protested the idea of taking pictures of the scene, now says the media should not have censored the photo.

The U.S. military has now abandoned the pool system it used in 1990 and 1991, and the internet has changed the way photos reach the public. Even if the AP did refuse to send out a photo, online outlets would certainly run it, and no managing editor would be able to prevent it from being shared across various social platforms, or being the subject of extensive op-ed and blog commentary. If anything, today’s controversies often center on the vast abundance of disturbing photographs, and the difficulty of putting them in a meaningful context.

Some have argued that showing bloodshed and trauma repeatedly and sensationally can dull emotional understanding. But never showing these images in the first place guarantees that such an understanding will never develop. “Try to imagine, if only for a moment, what your intellectual, political, and ethical world would be like if you had never seen a photograph,” the author Susie Linfield asks in The Cruel Radiance, her book on photography and political violence. Photos like Jarecke’s not only show that bombs drop on real people; they also make the public feel accountable. As David Carr wrote in The New York Times in 2003, war photography has “an ability not just to offend the viewer, but to implicate him or her as well.”

As an angry 28-year-old Jarecke wrote in American Photo in 1991: “If we’re big enough to fight a war, we should be big enough to look at it.”

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten