From time to time, I’ve wondered what it must be like to live in a truly tribal society. Watching Iraq or Syria these past few years, you get curious about how the collective mind can come so undone. What’s it like to see the contours of someone’s face, or hear his accent, or learn the town he’s from, and almost reflexively know that he is your foe? How do you live peacefully for years among fellow citizens and then find yourself suddenly engaged in the mass murder of humans who look similar to you, live around you, and believe in the same God, but whose small differences in theology mean they must be killed before they kill you? In the Balkans, a long period of relative peace imposed by communism was shattered by brutal sectarian and ethnic warfare, as previously intermingled citizens split into unreconcilable groups. The same has happened in a developed democratic society — Northern Ireland — and in one of the most successful countries in Africa, Kenya.

Tribal loyalties turned Beirut, Lebanon’s beautiful, cosmopolitan capital, into an urban wasteland in the 1970s; they caused close to a million deaths in a few months in Rwanda in the 1990s; they are turning Aung San Suu Kyi, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, into an enabler of ethnic cleansing right now in Myanmar. British imperialists long knew that the best way to divide and conquer was by creating “countries” riven with tribal differences. Not that they were immune: Even in successful modern democracies like Britain and Spain, the tribes of Scots and Catalans still threaten a viable nation-state. In all these places, the people involved have been full citizens of their respective nations, but their deepest loyalty is to something else.

But then we don’t really have to wonder what it’s like to live in a tribal society anymore, do we? Because we already do. Over the past couple of decades in America, the enduring, complicated divides of ideology, geography, party, class, religion, and race have mutated into something deeper, simpler to map, and therefore much more ominous. I don’t just mean the rise of political polarization (although that’s how it often expresses itself), nor the rise of political violence (the domestic terrorism of the late 1960s and ’70s was far worse), nor even this country’s ancient black-white racial conflict (though its potency endures).

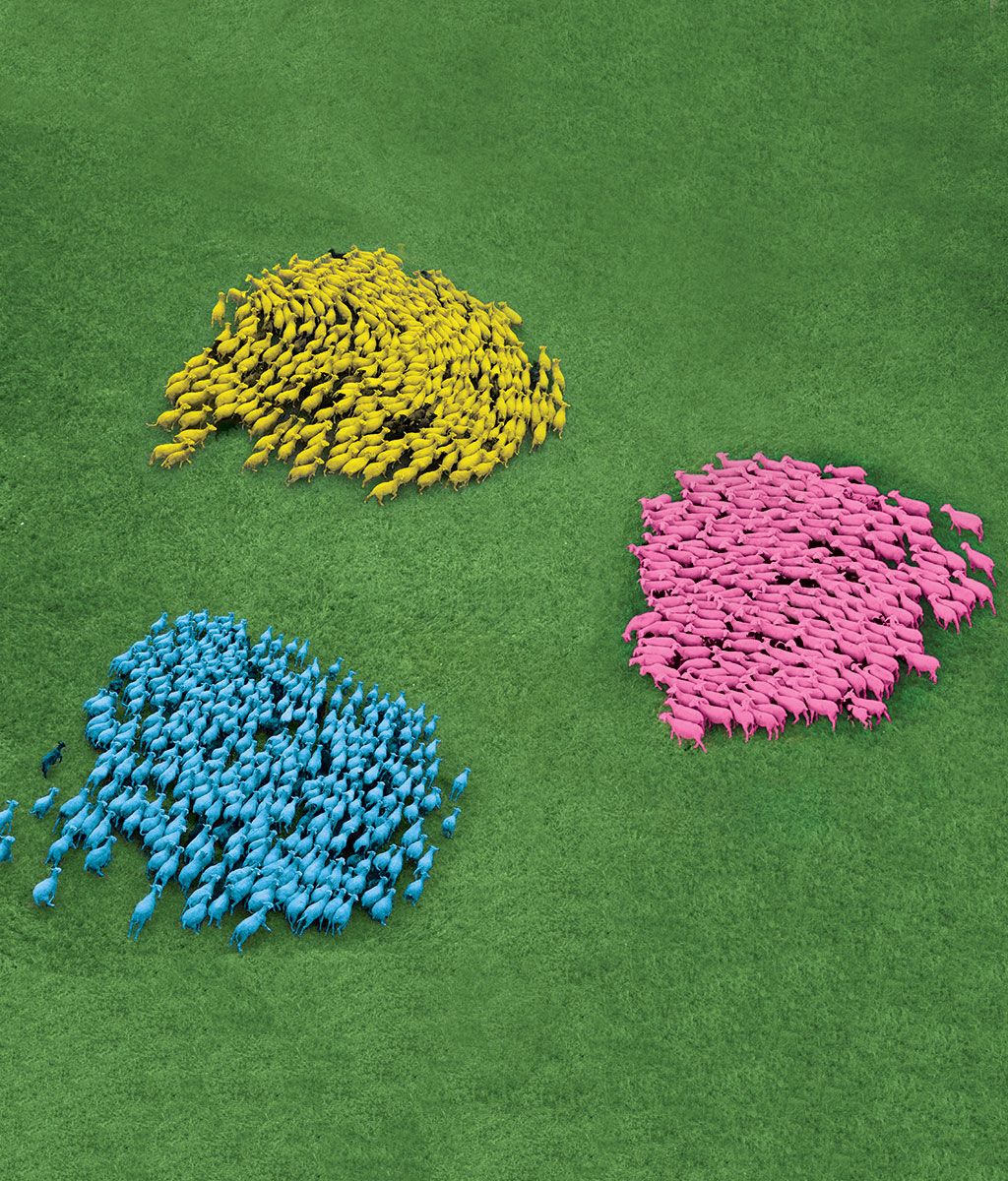

I mean a new and compounding combination of all these differences into two coherent tribes, eerily balanced in political power, fighting not just to advance their own side but to provoke, condemn, and defeat the other.

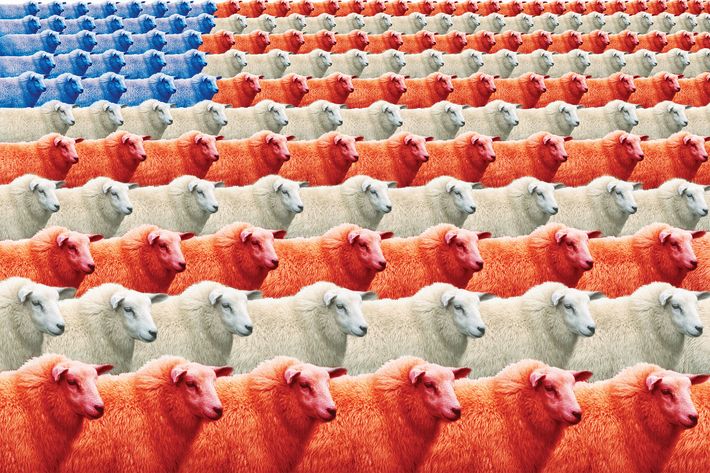

I mean two tribes whose mutual incomprehension and loathing can drown out their love of country, each of whom scans current events almost entirely to see if they advance not so much their country’s interests but their own. I mean two tribes where one contains most racial minorities and the other is disproportionately white; where one tribe lives on the coasts and in the cities and the other is scattered across a rural and exurban expanse; where one tribe holds on to traditional faith and the other is increasingly contemptuous of religion altogether; where one is viscerally nationalist and the other’s outlook is increasingly global; where each dominates a major political party; and, most dangerously, where both are growing in intensity as they move further apart.

The project of American democracy — to live beyond such tribal identities, to construct a society based on the individual, to see ourselves as citizens of a people’s republic, to place religion off-limits, and even in recent years to embrace a multiracial and post-religious society — was always an extremely precarious endeavor. It rested, from the beginning, on an 18th-century hope that deep divides can be bridged by a culture of compromise, and that emotion can be defeated by reason. It failed once, spectacularly, in the most brutal civil war any Western democracy has experienced in modern times. And here we are, in an equally tribal era, with a deeply divisive president who is suddenly scrambling Washington’s political alignments, about to find out if we can prevent it from failing again.

Tribalism, it’s always worth remembering, is not one aspect of human experience. It’s the default human experience. It comes more naturally to us than any other way of life. For the overwhelming majority of our time on this planet, the tribe was the only form of human society. We lived for tens of thousands of years in compact, largely egalitarian groups of around 50 people or more, connected to each other by genetics and language, usually unwritten. Most tribes occupied their own familiar territory, with widespread sharing of food and no private property. A tribe had its own leaders and a myth of its own history. It sorted out what we did every day, what we thought every hour.

Tribal cohesion was essential to survival, and our first religions emerged for precisely this purpose. As Dominic Johnson argues in his recent book God Is Watching You, almost all indigenous societies had a common concept of the supernatural, and almost all of them saw their worst threats — hunger, disease, natural disasters, a loss in battle — as a consequence of disobeying a god. Religion therefore fused with communal identity and purpose, it was integral to keeping the enterprise afloat, and the idea of people within a tribe believing in different gods was incomprehensible. Such heretics would be killed.

The tribes that best survived (and thereby transmitted their genes to us) were, moreover, those most acutely aware of outsiders and potential foes. A failure to notice incoming strangers could end your life in an instant, and an indifference to the appearances of other human beings could mean defeat at the hands of rivals or the collapse of a tribe altogether. And so we became a deeply cooperative species — but primarily with our own kind. The notion of living alongside people who do not look like us and treating them as our fellows was meaningless for most of human history.

Comparatively few actual tribes exist today, but that doesn’t mean that humans are genetically much different. In his book Tribe, Sebastian Junger relates a little-known fact about the Americans who pioneered the frontier. In the centuries in which white Europeans lived alongside Native American tribes, many Europeans split off from their fellow colonists, disappeared into the wilderness, and joined Indian society. Almost no natives voluntarily did the reverse. “Thousands of Europeans are Indians, and we have no examples of even one of those Aborigines having from choice become European,” wrote one 18th-century Frenchman. “There must be in their social bond something singularly captivating and far superior to anything to be boasted of among us.” That “something,” Junger argues, was being a member of a tribe.

Successful modern democracies do not abolish this feeling; they co-opt it. Healthy tribalism endures in civil society in benign and overlapping ways. We find a sense of belonging, of unconditional pride, in our neighborhood and community; in our ethnic and social identities and their rituals; among our fellow enthusiasts. There are hip-hop and country-music tribes; bros; nerds; Wasps; Dead Heads and Packers fans; Facebook groups. (Yes, technology upends some tribes and enables new ones.) And then, most critically, there is the Über-tribe that constitutes the nation-state, a megatribe that unites a country around shared national rituals, symbols, music, history, mythology, and events, that forms the core unit of belonging that makes a national democracy possible.

None of this is a problem. Tribalism only destabilizes a democracy when it calcifies into something bigger and more intense than our smaller, multiple loyalties; when it rivals our attachment to the nation as a whole; and when it turns rival tribes into enemies. And the most significant fact about American tribalism today is that all three of these characteristics now apply to our political parties, corrupting and even threatening our system of government.

If I were to identify one profound flaw in the founding of America, it would be its avoidance of our tribal nature. The founders were suspicious of political parties altogether — but parties defined by race and religion and class and geography? I doubt they’d believe a republic could survive that, and they couldn’t and didn’t foresee it. In fact, as they conceived of a new society that would protect the individual rights of all humanity, they explicitly excluded a second tribe among them: African-American slaves. Within a century, that moral and political blind spot cleaved the country down the middle and led to the kind of bloody, manic, and brutal tribal warfare we now think of as something that happens somewhere else.

But it did happen here, on a fault line that closely resembles today’s tribal boundary. For a century after the Civil War, this divide, while still strong, was nonetheless diluted by myriad other ethnic loyalties, as waves of European immigrants came to America and competed with each other as well as with those already here. Some new tribes, such as Mormons, were accommodated simply by the ever-expanding frontier. And in the first half of the 20th century, with immigration sharply curtailed after 1924, the world wars acted as great unifiers and integrators. Our political parties became less polarized by race, as the FDR Democrats managed to attract more black voters as well as ethnic and southern whites. By 1956, nearly 40 percent of black voters still backed the GOP.

But we all know what happened next. The re-racialization of our parties began with Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign in 1964, when the GOP lost almost all of the black vote. It accelerated under Nixon’s “southern strategy” in the wake of the civil-rights revolution. By Reagan’s reelection, the two parties began to cohere again into the Civil War pattern, and had simply swapped places.

The failed nomination of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court was perhaps the first moment that a hubristic GOP nominated a figure on the far right, and an increasingly vocal left upended previous norms for judicial hearings, using race and gender as political weapons. Mass illegal Latino immigration added to the tribal mix as the GOP, led most notably by Pete Wilson in California, became increasingly defined by white immigration restrictionists, and Hispanics moved to the Democrats. Newt Gingrich’s revolutionary GOP then upped the ante, treating President Bill Clinton as illegitimate from the start, launching an absurd impeachment crusade, and destroying the comity that once kept Washington from complete partisan dysfunction. Abortion and gay rights further split urban and rural America. By the 2000 election, we were introduced to the red-blue map, though by then we could already recognize the two tribes it identified as they fought to a national draw. Choosing a president under those circumstances caused a constitutional crisis, one the Supreme Court resolved at the expense of losing much of its nonpartisan, nontribal authority.

Then there were other accelerants: The arrival of talk radio in the 1980s, Fox News in the ’90s, and internet news and MSNBC in the aughts; the colossal blunder of the Iraq War, which wrecked the brief national unity after 9/11; and the rise of partisan gerrymandering that allowed the GOP to win, in 2016, 49 percent of the vote but 55 percent of House seats. (A recent study found that a full fifth of current districts are more convoluted than the original, contorted district that first gave us the term gerrymander in 1812.) The greatest threat to a politician today therefore is less a candidate from the opposing party than a more ideologically extreme primary opponent. The incentives for cross-tribal compromise have been eviscerated, and those for tribal extremism reinforced.

Add to this the great intellectual sorting of America, in which, for generations, mass college education sifted countless gifted young people from the heartland and deposited them in increasingly left-liberal universities and thereafter the major cities, from which they never returned, and then the shifting of our economy to favor the college-educated, which only deepened the urban-rural divide. The absence of compulsory military service meant that our wars would be fought disproportionately by one tribe, and the rise of radical Islamic terrorism only inflamed tribal suspicions. Then there’s the post-1965 wave of mass immigration, which disorients in ways that cannot be wished or shamed away; the decision among the country’s intellectual elite to junk the “melting pot” metaphor as a model for immigration in favor of “multiculturalism”; and the decline of Christianity as a common cultural language for both political parties — which had been critical, for example, to the success of the civil-rights movement.

The myths that helped us unite as a nation began to fray. We once had a widely accepted narrative of our origins, shared icons that defined us, and a common pseudo-ethnicity — “whiteness” — into which new immigrants were encouraged to assimilate. Our much broader ethnic mix and the truths of history make this much harder today — as, of course, they should. But we should be clear-eyed about the consequence. We can no longer think of the Puritans without acknowledging the genocide that followed them; we cannot celebrate our Founding Fathers without seeing that slavery undergirded the society they constructed; we must tear down our Confederate statues and relitigate our oldest rifts. Even the national anthem now divides those who stand from those who kneel. We dismantled many of our myths, but have not yet formed new ones to replace them.

The result of all this is that a lopsided 69 percent of white Christians now vote Republican, while the Democrats get only 31. In the last decade, the gap in Christian identification between Democrats and Republicans has increased by 50 percent. In 2004, 44 percent of Latinos voted Republican for president; in 2016, 29 percent did. Forty-three percent of Asian-Americans voted Republican in 2004; in 2016, 29 percent did. Since 2004, the most populous urban counties have also swung decisively toward the Democrats, in both blue and red states, while rural counties have shifted sharply to the GOP. When three core components of a tribal identity — race, religion, and geography — define your political parties, you’re in serious trouble.

Some countries where tribal cleavages spawned by ethnic and linguistic differences have long existed understand this and have constructed systems of government designed to ameliorate the consequences. Unlike the U.S., they encourage a culture of almost pathological compromise, or build constitutions that, unlike our own, take tribal conflict seriously. They often have a neutral head of state — a constitutional monarch or nonpartisan president — so that the legitimacy of the system is less easily defined by one tribe or the other. They tend to have proportional representation and more than two parties, so it’s close to impossible for one party to govern without some sort of coalition. In the toughest cases, they have mandatory inclusion of minority parties in the government.

In Northern Ireland, for example, since the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, there are intricate arrangements in which no regional government for the province can exist without support from at least two parties representing the Catholic minority and the Protestant majority. The first minister and the deputy first minister have to be from different parties, one Catholic and one Protestant. If one or the other drops out, power reverts to Westminster. The Belgian government, to take another example, is required to have both French- and Flemish-speaking parties, representing the two linguistic and cultural tribes that make up the country.

These contrivances are not fail-safe, especially if the divisions are too great — such as Cyprus’s experiment in the 1960s. But they can channel tribal conflict constructively and thereby weaken it. The Netherlands is the clearest success story. Its three main tribes (or “pillars,” as they became known) were, for many years, Catholic, Protestant, and socialist. Each had its own political culture, media, and unions. But these were divided into five parties (one socialist, one conservative, one Catholic, and two Protestant). In practice, this required tribal cooperation through constant coalition governments that gravitated toward the center. Over time, as secularism took hold, the Netherlands evolved into a much more familiar variety of ideological parties, but its tradition of compromising, coalition governments remains.

The United States is built on a very different set of institutions. There is no neutral presidency here, and so when a rank tribalist wins the office and governs almost entirely in the interests of the hardest core of his base, half the country understandably feels as if it were under siege. Our two-party, winner-take-all system only works when both parties are trying to appeal to the same constituencies on a variety of issues.

Our undemocratic electoral structure exacerbates things. Donald Trump won 46 percent of the vote, attracting 3 million fewer voters than his opponent, but secured 56 percent of the Electoral College. Republicans won 44 percent of the vote in the Senate seats up for reelection last year, but 65 percent of the seats. To have one tribe dominate another is one thing; to have the tribe that gained fewer votes govern the rest — and be the head of state — is testing political stability.

What you end up with is zero-sum politics, which drags the country either toward alternating administrations bent primarily on undoing everything their predecessors accomplished, or the kind of gridlock that has dominated national politics for the past seven years — or both. Slowly our political culture becomes one in which the two parties see themselves not as participating in a process of moving the country forward, sometimes by tilting to the right and sometimes to the left, as circumstances permit, alternating in power, compromising when in opposition, moderating when in government — but one where the goal is always the obliteration of the other party by securing a permanent majority, in an unending process of construction and demolition.

And so by 2017, 41 percent of Republicans and 38 percent of Democrats said they disagreed not just with their opponents’ political views but with their values and goals beyond politics as well. Nearly 60 percent of all Americans find it stressful even to talk about Trump with someone who disagrees with them. A Monmouth poll, for good measure, recently found that 61 percent of Trump supporters say there’s nothing he could do to make them change their minds about him; 57 percent of his opponents say the same thing. Nothing he could do.

One of the great attractions of tribalism is that you don’t actually have to think very much. All you need to know on any given subject is which side you’re on. You pick up signals from everyone around you, you slowly winnow your acquaintances to those who will reinforce your worldview, a tribal leader calls the shots, and everything slips into place. After a while, your immersion in tribal loyalty makes the activities of another tribe not just alien but close to incomprehensible. It has been noticed, for example, that primitive tribes can sometimes call their members simply “people” while describing others as some kind of alien. So the word Inuit means people, but a rival indigenous people, the Ojibwe, call them Eskimos, which, according to lore, means “eaters of raw meat.”

When criticized by a member of a rival tribe, a tribalist will not reflect on his own actions or assumptions but instantly point to the same flaw in his enemy. The most powerful tribalist among us, Trump, does this constantly. When confronted with his own history of sexual assault, for example, he gave the tiniest of apologies and immediately accused his opponent’s husband of worse, inviting several of Bill Clinton’s accusers to a press conference. But in this, he was only reflecting the now near-ubiquitous trend of “whataboutism,” as any glance at a comments section or a cable slugfest will reveal. The Soviets perfected this in the Cold War, deflecting from their horrific Gulags by pointing, for example, to racial strife in the U.S. It tells you a lot about our time that a tactic once honed in a global power struggle between two nations now occurs within one. What the Soviets used against us we now use against one another.

In America, the intellectual elites, far from being a key rational bloc resisting this, have succumbed. The intellectual right and the academic left have long since dispensed with the idea of a mutual exchange of ideas. In a new study of the voting habits of professors, Democrats outnumber Republicans 12 to 1, and the imbalance is growing. Among professors under 36, the ratio is almost 23 to 1. It’s not a surprise, then, that once-esoteric neo-Marxist ideologies — such as critical race and gender theory and postmodernism, the bastard children of Herbert Marcuse and Michel Foucault — have become the premises of higher education, the orthodoxy of a new and mandatory religion. Their practical implications — such as “safe spaces,” speech regarded as violence, racially segregated graduation ceremonies, the policing of “micro-aggressions,” the checking of “white privilege” — are now embedded in the institutions themselves.

Conservative dissent therefore becomes tribal blasphemy. Free speech can quickly become “hate speech,” “hate speech” becomes indistinguishable from a “hate crime,” and a crime needs to be punished. Many members of the academic elite regard opposing views as threats to others’ existences, and conservative speakers often can only get a hearing on campus under lockdown. This seeps into the broader culture. It leads directly to a tech entrepreneur like Brendan Eich being hounded out of a company, Mozilla, he created because he once opposed marriage equality, or a brilliant coder, James Damore, being fired from Google for airing civil, empirical arguments against the left-feminist assumptions behind the company’s employment practices.

It’s why a young gay freelance writer, Chadwick Moore, could have a record of solid journalism, write a balanced profile of Milo Yiannopoulos for Outmagazine, and then be subjected to an avalanche of bile from readers and a public denunciation signed by many of his fellow gay journalists. He lost his relationship with the magazine shortly thereafter. Moore is a fascinating case in how tribalism now infects everything. After being ostracized by his own tribe, he flipped, turned into a parody of MAGA conformity, and became an employee of Milo Inc.

There is, of course, an enormous conservative intellectual counter-Establishment, an often incestuous network of think tanks, foundations, journals, and magazines that exists outside of universities. It, too, has fomented its own orthodoxies, policed dissent, and punished heresy.

Conservatism thrived in America when it was dedicated to criticizing liberalism’s failures, engaging with it empirically, and offering practical alternatives to the same problems. It has since withered into an intellectual movement that does little but talk to itself and guard its ideological boundaries. To be a conservative critic of George W. Bush, for example, meant risking not just social ostracism but, for many, loss of livelihood. I recall being applauded by the conservative media — and trashed by the left — when I endorsed Bush in 2000 and used my blog to champion the Iraq War. But when I realized the depth of my mistake, regretted my own tribal rhetoric, and wrote about it, I was immediately transformed into an unmentionable leftist. My writing career survived because I had my own blog and a foot in liberal media. But most others have no such escape routes.

And so, among tribal conservatives, the Iraq War remained a taboo topic when it wasn’t still regarded as a smashing success, tax cuts were still the solution to every economic woe, free trade was all benefit and no cost, and so on. Health care was perhaps the most obvious example of this intellectual closure. Republican opposition to the Affordable Care Act was immediate and total. Even though the essential contours of the policy had been honed at the Heritage Foundation, even though a Republican governor had pioneered it in Massachusetts, and even though that governor became the Republican nominee in 2012, the anathematization of it defined the GOP for seven years. After conservative writer David Frum dared to argue that a moderate, market-oriented reform to the health-care system was not the ideological hill for the GOP to die on, he lost his job at the American Enterprise Institute. When it actually came to undoing the reform earlier this year, the GOP had precious little intellectual capital to fall back on, no alternative way to keep millions insured, no history of explaining to voters outside their own tribe what principles they were even trying to apply.

George Orwell famously defined this mind-set as identifying yourself with a movement, “placing it beyond good and evil and recognising no other duty than that of advancing its interests.” It’s typified, he noted, by self-contradiction and indifference to reality. And so many severe critics of George W. Bush’s surveillance policies became oddly muted when Obama adopted most of them; Democrats looked the other way as Obama ramped up deportations to levels higher than Trump’s rate so far. Republicans, in turn, were obsessed with the national debt when Obama was in office, despite the deepest recession in decades. But the minute Trump came to power, they couldn’t be more enthusiastic about a tax package that could add trillions of dollars to it. No tribe was more federalist when it came to marijuana laws than liberals; and no tribe was less federalist when it came to abortion. Reverse that for conservatives. For the right-tribe, everything is genetic except homosexuality; for the left-tribe, nothing is genetic except homosexuality. During the Bush years, liberals inveighed ceaselessly against executive overreach; under Obama, they cheered when he used his executive authority to alter immigration laws and impose new environmental regulations by fiat.

As for indifference to reality, today’s Republicans cannot accept that human-produced carbon is destroying the planet, and today’s Democrats must believe that different outcomes for men and women in society are entirely a function of sexism. Even now, Democrats cannot say the words illegal immigrants or concede that affirmative action means discriminating against people because of their race. Republicans cannot own the fact that big tax cuts have not trickled down, or that President Bush authorized the brutal torture of prisoners, thereby unequivocally committing war crimes. Orwell again: “There is no crime, absolutely none, that cannot be condoned when ‘our’ side commits it. Even if one does not deny that the crime has happened, even if one knows that it is exactly the same crime as one has condemned in some other case … still one cannot feel that it is wrong.” That is as good a summary of tribalism as you can get, that it substitutes a feeling — a really satisfying one — for an argument.

When a party leader in a liberal democracy proposes a shift in direction, there is usually an internal debate. It can go on for years. When a tribal leader does so, the tribe immediately jumps on command. And so the Republicans went from free trade to protectionism, and from internationalism to nationalism, almost overnight. For decades, a defining foreign-policy concern for Republicans was suspicion of and hostility to the Soviet Union and Russia. In the 2012 election, Mitt Romney called Moscow the No. 1 geopolitical enemy of the United States. And yet between 2014 and 2017, a period when Putin engaged in maximal provocation, occupying Crimea and moving troops into Ukraine, Republican approval of the authoritarian thug in the Kremlin leapt from 10 to 32 percent.

And then there is the stance of white Evangelicals, a pillar of the red tribe. Among their persistent concerns has long been the decline of traditional marriage, the coarsening of public discourse, and the centrality of personal virtue to the conduct of public office. In the 1990s, they assailed Bill Clinton as the font of decadence; then they lionized George W. Bush, who promised to return what they often called “dignity” to the Oval Office. And yet when a black Democrat with exemplary personal morality, impeccable public civility, a man devoted to his wife and children and a model for African-American fathers, entered the White House, they treated him as a threat to civilization. Even as he gave speeches drenched in Christian allegory and offered a eulogy in Charleston that ended with a cathartic rendition of “Amazing Grace,” they retained a suspicion that he was secretly a Muslim. And when they encountered a foulmouthed pagan who bragged of grabbing women by the pussy, used the tabloids to humiliate his wife, married three times, boasted about the hotness of his own daughter, touted the size of his own dick in a presidential debate, and spoke of avoiding STDs as his personal Vietnam, they gave him more monolithic support than any candidate since Reagan, including born-again Bush and squeaky-clean Romney. In 2011, a poll found that only 30 percent of white Evangelicals believed that private immorality was irrelevant for public life. This month, the same poll found that the number had skyrocketed to 72 percent.

Total immersion within one’s tribe also leads to increasingly extreme ideas. The word “hate,” for example, has now become a one-stop replacement for a whole spectrum of varying, milder emotions involved with bias toward others: discomfort, fear, unease, suspicion, ignorance, confusion. And it has even now come to include simply defending traditional Christian, Jewish, and Muslim doctrine on questions such as homosexuality.

Or take the current promiscuous use of the term “white supremacist.” We used to know what that meant. It meant advocates and practitioners of slavery, believers in the right of white people to rule over all others, subscribers to a theory of a master race, Jim Crow supporters, George Wallace voters. But it is now routinely used on the left to mean, simply, racism in a multicultural America, in which European-Americans are a fast-evaporating ethnic majority. It’s a term that implies there is no difference in race relations between America today and America in, say, the 1830s or the 1930s. This rhetoric is not just untrue, it is dangerous. It wins no converts, and when actual white supremacists march in the streets, you have no language left to describe them as any different from, say, all Trump supporters, including the 13 percent of black men who voted for him.

Liberals should be able to understand this by reading any conservative online journalism and encountering the term “the left.” It represents a large, amorphous blob of malevolent human beings, with no variation among them, no reasonable ideas, nothing identifiably human at all. Start perusing, say, townhall.com, and you will soon stumble onto something like this, written recently by one of my favorite right-tribalists, Kurt Schlichter: “They hate you. Leftists don’t merely disagree with you. They don’t merely feel you are misguided. They don’t think you are merely wrong. They hate you. They want you enslaved and obedient, if not dead. Once you get that, everything that is happening now will make sense.” And, yes, everything will. How does Schlichter describe the right? “Normals.” It’s the Inuit and the Eskimos all over again.

This atmosphere can affect even the finest minds. I think of Ta-Nehisi Coates, the essayist and memoirist. Not long ago, he was a subtle, complicated, and beautiful writer. He could push back against his own tribe. He could write critically of the idea that “there never is any black agency — to be African-American is to be an automaton responding to either white racism or cultural pathology. No way you could actually have free will.” He could persuasively push against “nihilism and paranoia” among his own, to champion the idea of being “critical, not just of the larger white narrative, but of the narrative put forth by those around you.” He could speak of street culture as someone who lived it and yet knew, as he put it in an essay called“A Culture of Poverty,” that “ ‘I ain’t no punk’ may shield you from neighborhood violence. But it cannot shield you from algebra, when your teacher tries to correct you. It cannot shield you from losing hours, when your supervisor corrects your work.” He could do this while brilliantly conveying the systemic racism that crushes the souls of so many black Americans.

He remains a vital voice, but in more recent years, a somewhat different one. His mood has become much gloomier. He calls the Obama presidency a “tragedy,” and describes many Trump supporters as “not so different from those same Americans who grin back at us in lynching photos.” He’s written about how watching cops and firefighters enter the smoldering World Trade Center instantly reminded him of cops mistreating blacks: They “were not human to me.” In his latest essay in the Atlantic, analyzing why Donald Trump won the last election, he dismisses any notion that economic distress might have played a role as “empty” and ignores other factors, such as Hillary Clinton’s terrible candidacy, the populist revolt against immigration that had become a potent force across the West, and the possibility that the pace of social change might have triggered a backlash among traditionalists. No, there was one meaningful explanation only: white supremacism. And those who accept, as I do, that racism was indeed a big part of the equation but also saw other factors at work were simply luxuriating in our own white privilege because we are never under “racism’s boot.”

A writer is entitled to shift perspective. What’s more salient is his audience. He once had a small but devoted and querulous readership for his often surprising blog. Today, his works are huge best sellers, and it is deemed near blasphemous among liberals to criticize them.

How to unwind this increasingly dangerous dysfunction? It’s not easy to be optimistic with Trump as president. And given his malignant narcissism, despotic instincts, absence of empathy, and constant incitement of racial and xenophobic hatred, it’s extremely hard not to be tribal in return. There is no divide he doesn’t want to deepen, no conflict he doesn’t want to start or intensify. How on earth can we not “resist”?

But we should not delude ourselves that this is all a Trump problem. What Obama could not overcome would have buried Hillary Clinton, who, almost uniquely in public life, carries the scars of our tribal era. Her campaignmade no effort to persuade “deplorables,” just to condemn them, and her core strategy was not to engage those on the fence but to maximize the turnout of her demographic tribe.

In fact, the person best positioned to get us out of this tribal trap would be … well … bear with me … Trump. The model would be Bill Clinton, the first president to meet our newly configured divide. Clinton leveraged the loyalty of Democrats thrilled to regain the White House in order to triangulate toward centrist compromises with the GOP. You can argue about the merits of the results, but he was able to govern, to move legislation forward, to reform welfare, reduce crime, turn the deficit into a surplus, survive impeachment, and end his term a popular president.

Trump is as much an opportunist as a tribalist; he won the presidency by having an intuitive, instinctive grasp of how to inflame and exploit our tribal divide. His base is therefore more fanatically loyal and his policy views even more, shall we say, flexible than Clinton’s. His recent dealings with the Democratic congressional leadership have flummoxed party leaders and disrupted our political storytelling. That’s something worth celebrating. His new openness to trade legislating DACA in return for stronger immigration enforcement is especially good news. If Trump is right that he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue and his followers would still support him, he’s surely uniquely capable of cutting deals with the Democrats while keeping much of the Republican base in line (and kneecapping Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell). Two new polls back this up. Rasmussen found that 72 percent of Republican voters support Trump’s working with Democrats; YouGov found that Republicans backed Trump’s deal with Schumer and Pelosi by 62 to 18 percent.

The Democrats are now, surprisingly, confronting a choice many thought they would only face in a best-case-scenario midterm election, and their political calculus is suddenly much more complicated than pure resistance. Might the best interest of the country be served by working with Trump? And if they do win the House in 2018, should they seek to destroy Trump’s presidency, much like GOP leaders in Congress chose to do with Obama? Should they try to end it through impeachment, as the GOP attempted with Bill Clinton? Or could they try to moderate the tribal divide? Maybe it’s no longer a complete fantasy that they might even find a compromise that reforms the Affordable Care Act while allowing Trump to claim he replaced it — and use that as a model for further collaboration. But if Democratic leaders choose to de-escalate our tribal war rather than to destroy their political nemesis, would their base revolt?

Or maybe we can just reassure ourselves that our tribalism is mainly a function of the older generation’s racial and cultural panic and we will slowly move through and past it. Maybe Trump’s victory is just one last hurrah of an older, whiter American identity, that we can outlast without a cathartic crisis or conflict. One trouble with this hopefulness is that “whiteness” is a subjective term. It’s possible that more Latinos will identify as white in the future, as other immigrant minorities have over time, thereby maintaining our tribal balance. It’s also possible that our ethnic and cultural divide could very much worsen in the meantime, especially as the demise of the old white majority becomes closer to statistical reality. White Christians are panicked and paranoid about religious freedom now. How will they feel when vastly more secular and multiracial generations come to power? And if the Democrats try to impeach a president who has no interest in the stability or integrity of our liberal democracy, and if his base sees it, as they will, as an Establishment attempt at nullifying their vote, are we really prepared to handle the civil unrest and constitutional crisis that would almost certainly follow?

Tribalism is not a static force. It feeds on itself. It appeals on a gut level and evokes emotions that are not easily controlled and usually spiral toward real conflict. And there is no sign that the deeper forces that have accelerated this — globalization, social atomization, secularization, media polarization, ever more multiculturalism — will weaken. The rhetorical extremes have already been pushed further than most of us thought possible only a couple of years ago, and the rival camps are even more hermetically sealed. In 2015, did any of us anticipate that neo-Nazis would be openly parading with torches on a college campus or that antifa activists would be proudly extolling violence as the only serious response to the Trump era?

As utopian as it sounds, I truly believe all of us have to at least try to change the culture from the ground up. There are two ideas that might be of help, it seems to me. The first is individuality. I don’t mean individualism. Nothing is more conducive to tribalism than a sea of disconnected, atomized individuals searching for some broader tribe to belong to. I mean valuing the unique human being — distinct from any group identity, quirky, full of character and contradictions, skeptical, rebellious, immune to being labeled or bludgeoned into a broader tribal grouping. This cultural antidote to tribalism, left and right, is still here in America and ready to be rediscovered. That we expanded the space for this to flourish is one of the greatest achievements of the West.

Perhaps I’m biased because I’m an individual by default. I’m gay but Catholic, conservative but independent, a Brit but American, religious but secular. What tribe would ever have me? I may be an extreme case, but we all are nonconformist to some degree. Nurturing your difference or dissent from your own group is difficult; appreciating the individuality of those in other tribes is even harder. It takes effort and imagination, openness to dissent, even an occasional embrace of blasphemy.

And, at some point, we also need mutual forgiveness. It doesn’t matter if you believe, as I do, that the right bears the bulk of the historical blame. No tribal conflict has ever been unwound without magnanimity. Yitzhak Rabin had it, but it was not enough. Nelson Mandela had it, and it was. In Colombia earlier this month, as a fragile peace agreement met public opposition, Pope Francis insisted that grudges be left behind: “All of us are necessary to create and form a society. This isn’t just done with the ‘pure-blooded’ ones, but rather with everyone. And here is where the greatness of the country lies, in that there is room for all and all are important.” If societies scarred by recent domestic terrorism can aim at this, why should it be so impossible for us?

But this requires, of course, first recognizing our own tribal thinking. So much of our debates are now an easy either/or rather than a complicated both/and. In our tribal certainties, we often distort what we actually believe in the quiet of our hearts, and fail to see what aspects of truth the other tribe may grasp.

Not all resistance to mass immigration or multiculturalism is mere racism or bigotry; and not every complaint about racism and sexism is baseless. Many older white Americans are not so much full of hate as full of fear. Equally, many minorities and women face genuine blocks to their advancement because of subtle and unsubtle bias, and it is not mere victim-mongering. We also don’t have to deny African-American agency in order to account for the historic patterns of injustice that still haunt an entire community. We need to recall that most immigrants are simply seeking a better life, but also that a country that cannot control its borders is not a country at all. We’re rightly concerned that religious faith can easily lead to intolerance, but we needn’t conclude that having faith is a pathology. We need not renounce our cosmopolitanism to reengage and respect those in rural America, and we don’t have to abandon our patriotism to see that the urban mix is also integral to what it means to be an American today. The actual solutions to our problems are to be found in the current no-man’s-land that lies between the two tribes. Reentering it with empiricism and moderation to find different compromises for different issues is the only way out of our increasingly dangerous impasse.

All of this runs deeply against the grain. It’s counterintuitive. It’s emotionally unpleasant. It fights against our very DNA. Compared with bathing in the affirming balm of a tribe, it’s deeply unsatisfying. But no one ever claimed that living in a republic was going to be easy — if we really want to keep it.

*This article appears in the September 18, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2017/09/can-democracy-survive-tribalism.html

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten