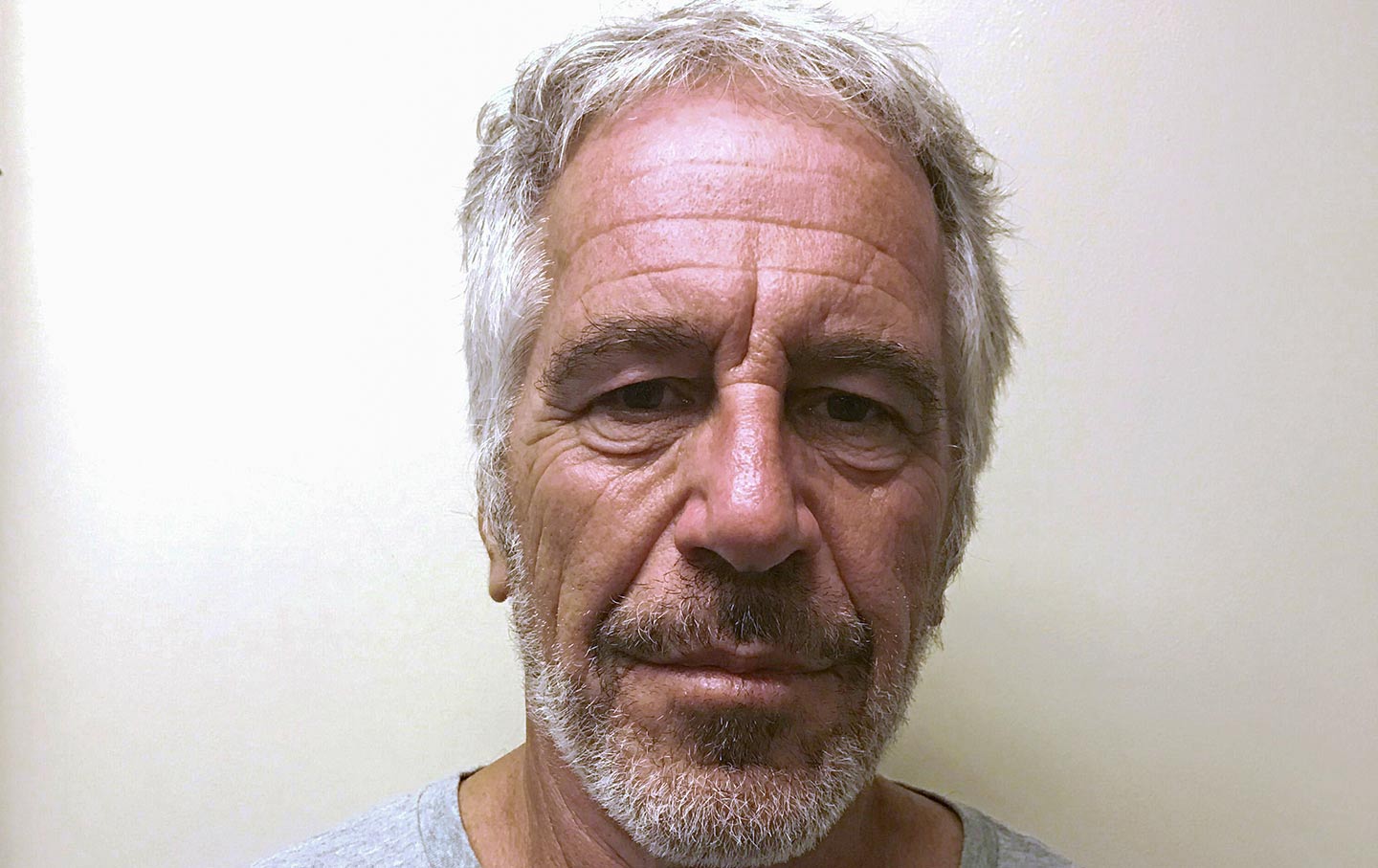

On Saturday night, the BBC aired an interview with Prince Andrew, during which he offered a singularly unpersuasive account of his friendship with Jeffrey Epstein, the notorious serial sex offender who died in a Manhattan jail in August. Andrew vehemently denied allegations that he sexually assaulted an underage girl, Virginia Roberts, who was one of Epstein’s victims. The interviewer, Emily Maitlis, queried Andrew’s decision to spend several days at Epstein’s Manhattan residence during a 2010 visit that the prince said was designed to end the relationship. Andrew let out a long sigh and replied, “It was a convenient place to stay.” Andrew went on to say that staying with Epstein felt like “the honorable and right thing to do and I admit that my judgement was probably colored by my tendency to be too honorable.” Maitlis pointed out that witnesses, backed by photographs, testified that young girls were seen coming in and going out of Epstein’s residence during this visit. Andrew responded that Epstein’s home was almost “a railway station,” with innumerable strangers passing through.

Andrew pounced on the claim made by his accuser that he was profusely sweating the night of the attack. “I have a peculiar medical condition which is that I don’t sweat or I didn’t sweat at the time,” Andrew asserted. His remarkable lack of perspiration, which he avers has now been cured, was due to “an overdose of adrenalin in the Falklands war.” A medical expert interviewed by The Express, an English newspaper, was baffled by the idea that an adrenaline rush could have that impact.

Even ardent monarchists were appalled by Andrew’s performance. Dickie Arbiter, the former press secretary for the queen, reprimanded Andrew for showing “no remorse” and “an abundance of arrogance.”

Prince Andrew’s bizarre comments shouldn’t be seen as just the personal folly of a dim-witted son of privilege unable to admit his misdeeds. They reflect something larger: the absence of anything approaching a reckoning with Jeffrey Epstein’s life of crime, coupled with lingering questions about his death.

Jeffrey Epstein’s death, ruled a suicide by the New York City medical examiner’s office, has brought no closure. Epstein’s estranged brother, engaged in an effort to take over an estate under siege by lawsuits, hired a forensic pathologist, Dr. Michael Baden, to review the case. Baden concluded that the marks on Epstein’s neck were more compatible with murder than suicide. But Baden, a notorious publicity hound who was fired as the city’s chief medical examiner in 1979 for poor record keeping, can hardly be taken as the last word. As Sarah Weinman suggested in New York magazine, Baden’s second opinion needs the reliability test of a third opinion.

The cloud surrounding Epstein’s death extends beyond the question of suicide. There are ongoing investigations of the systematic failures that occurred the night Epstein died, including the fact that Epstein, who had reportedly tried to kill himself, wasn’t on suicide watch; the fact that cameras outside his cell weren’t working; and the fact that security guards, who were overworked, failed to make the proper rounds.

All of this is catnip for conspiracy theorists, who with good reason feel that the official story of bungling is unpersuasive. Epstein-skepticism can be found all over the political spectrum, appealing especially to those inclined to distrust the political elite. On the left, the podcast TruAnon, hosted Liz Franczak and Brace Belden, emphasizes Epstein’s connections to the worlds of high politics (including the intelligence community) and stratospheric wealth. You don’t have to make any sort of leap of faith to follow the argument. After all, Epstein hung out with elite figures like Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, and Bill Gates. Alex Acosta, who as US Attorney in Miami in 2008 negotiated a sweetheart deal to minimize Epstein’s punishment for his crimes, reportedly explained his actions by saying, “I was told Epstein ‘belonged to intelligence’ and to leave it alone.”

But left-wing Epstein obsessives are a minority. What’s increasingly clear is that the mystery of the Epstein case, combined with the reluctance of the mainstream media to tackle the topic for fear of seeming conspiratorial, is offering an opening to the far right. Much of the Epstein story appeals to the right-wing imagination. It can be used to revive existing narratives of the perfidy of Bill and Hillary Clinton—and to lash out against the dishonesty of the mainstream media. It also offers a chance to harvest the inchoate anti-system emotions shared by many Americans who aren’t necessarily right wing.

Further, in a period when Donald Trump is mired in scandal, Epstein offers the distraction of a much bigger scandal. To be sure, Trump himself is implicated in the Epstein case, having been a boon companion to Epstein for many years when they shared a similar libertine lifestyle before a falling-out in 2004. Alex Acosta was Trump’s secretary of labor until the resurfacing of the Epstein case led to his resignation. And Epstein died in a prison run by Trump’s administration. Still, for whatever reason, right-wingers seem to think the facts of the Epstein scandal will reflect more poorly on Trump’s enemies than on Trump himself.

The now popular meme “Epstein didn’t kill himself” offers the thrill of secret lore, of saying something that could very well be true but is still shocking to polite society. Last Wednesday, just as impeachment hearings were starting, Arizona Representative Paul A. Gosar, one of the most right-wing figures in the GOP, let loose with a string of tweets berating Donald Trump’s critics. If you took the first letter of 23 or those tweets in order, you’d get an acrostic message: “Epstein didn’t kill himself.”

According to The Washington Post, the meme “Epstein didn’t kill himself” first took off after the words were uttered by a Navy Seal talking about military dogs on a Fox News segment on October 29. After that segment ran, according to the newspaper, “Seemingly overnight, those last four words, or something close to them, were everywhere: Belted out in videos posted by teenagers to TikTok, the social media platform beloved by Generation Z. Hacked into a roadside traffic sign in Modesto, Calif. Uttered by a University of Alabama student during a live report on MSNBC, hours before the president was set to appear at the school’s football game.”

There’s reason to resist joining the “Epstein didn’t kill himself” bandwagon. Conspiracy mongering is, in many ways, the opposite of progressive activism. The conspiracy theorist is engaged in the search for gnomic hidden truths, working like a detective piecing together a puzzle. That’s a far cry from the public world of activism, where agitation and organizing is almost always based on shared awareness of visible problems.

Yet the many unsolved Epstein riddles shouldn’t be left to the Gosars of the world. Nor do they have to be addressed with the feverish paranoia of obsessives who make spiderweb charts that link together all facts of the case. There’s ample room for a public reckoning, one that would focus not just on Epstein’s death but also, and much more urgently, on his life. Because the scandal of Epstein’s death is a flickering shadow compared to the robust scandal of his life.

The BBC interview with Prince Andrew was a good example of how the Epstein conundrum can be handled going forward. (The press response in Britain, where the story ran on the front pages of newspapers across the political spectrum, contrasts with that in the United States, where the mainstream media seems to have forgotten about Epstein.) Andrew’s answers were wholly inadequate, but that in itself clarified the issue. It’s important to know that Andrew, when faced with a rigorous grilling, has no plausible explanation for his friendship with Epstein.

We’ll continue to need a fierce press investigation of Epstein’s case, coupled with political activism pushing for an independent review of his death. This work is necessary for many reasons, not least as a way of precluding exploitation of the case by the far right.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten