Policing the Black Man

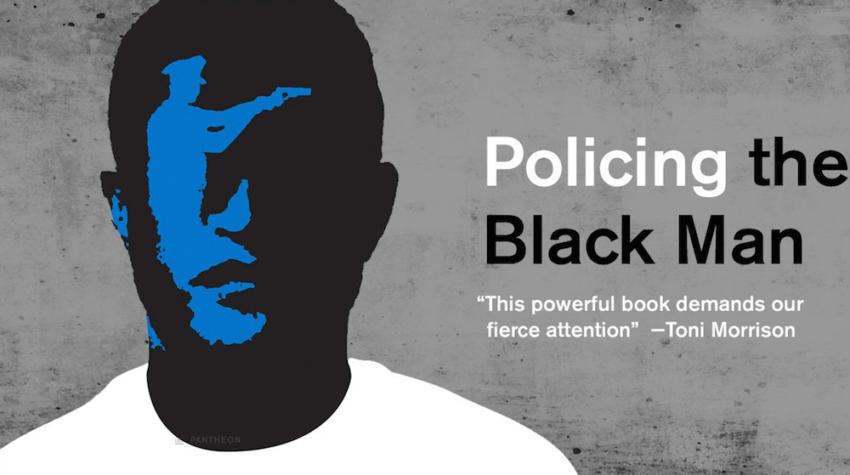

“Policing the Black Man”

A book edited by Angela J. Davis

“Policing the Black Man”

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

For several years in my UCLA class on “Race, Racism, and the Law,” many African-American (and Latino) students have discussed their harassment at the hands of police authorities in Los Angeles and elsewhere. They have spoken with anguish, detailing their pain, embarrassment, humiliation and anger. These young men, and some women, are academically accomplished, middle class, and law-abiding. All too often, these unpleasant encounters with police have occurred in the affluent community of Westwood and not infrequently on the UCLA campus.

Everyone in black communities knows of such unpleasant encounters with police, as well as broader injustices with the criminal justice system in general. Millions of African-Americans understand that people involved with any aspect of law enforcement, including police, school officials, prosecutors, judges, and jail and prison officers routinely act in racist ways, even if they are not explicitly conscious of their motivations. This is so well understood among most African-Americans that no scholarly or scientific studies are necessary to confirm such obvious historical truths.

Still, far too many white Americans still believe that civil rights advances in recent decades have solved racial problems, and that African-American complaints about police misconduct or worse are exaggerated or unfounded. A new book of essays, “Policing the Black Man,” edited by American University law professor Angela J. Davis, devastatingly shatters this myth. These essays reveal the tragic history of racial injustice in American law and especially how black men and boys have been and remain the chief victims of every feature of the system, including arrest, prosecution, sentencing, and imprisonment.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Policing the Black Man” at Google Books.

Not surprisingly, many of the essays detail some of the most horrific police beatings and killings that have garnered domestic and international attention: Abner Louima, Sean Bell, Amadou Diallo, Oscar Grant, Michael Brown, Walter Scott, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray and Philando Castile. None of the police officers involved in these cases has been convicted in court of any crimes, except former South Carolina police officer Michael Slager, who pleaded guilty to using excessive force in the 2015 shooting death of Walter Scott. These are only a few incidents, brought to light with media exposure; many others are likely to have occurred while no one was present with a camera or video recorder.

Many of the book’s essays address some of the historical roots of the racist practices of contemporary policing. Slave patrols, which began in the 18th century, consisted of white citizen patrols who searched slave quarters and sought to abort slave escapes or rebellions. They were the precursors to the police forces of the modern era.

The laws themselves, as well as specific practices, likewise contributed to the present discriminatory police and other legal arrangements against black men. Racist provisions in the original constitutional text, horrific Supreme Court decisions like Dred Scott v. Sandford, the civil rights cases, and Plessy v. Ferguson, the post Civil War Black Codes, lynching, convict leasing, and the infamous history of Jim Crow laws and practices all contributed to the grim contemporary reality of racist law enforcement practices. This history has led inexorably to African-Americans being 2.5 times more likely to be arrested than whites, 49 percent of black men expected to be arrested at least once by age 23, and being killed at far higher rates by police than white men.

A crucial dimension of the problem is explored in Katheryn Russell-Brown’s essay, “Making Implicit Bias Explicit.” Racial disparity in police stops, arrests, bail decisions, prosecutorial charging decisions, jury verdicts, sentencing, parole, and other determinations all reflect the deep implicit racial biases that have pervaded white attitudes for centuries in this country. The research is clear and depressing, as the author reveals: “Black skin evokes a different unconscious response than white skin.” A widespread and unacknowledged association between dark brown skin, wide noses and full lips leads many law enforcement officials at all levels to assume criminality and guilt.

Black Americans are perfectly aware of this reality. As Russell-Brown notes in her essay, the old expression in the black community is pervasive: “If you’re white you’re all right; if you’re brown, stick around; but if you’re black, get back.” African-American artists for generations have captured this feature of institutional racism.

Los Angeles artist Derrick Maddox, for example, in “You See Sinner, I See Saint,” reveals America’s racial divide by using the portrait of a young, dreadlocked, black man mounted on a wooden board. Above the portrait, “you see sinner” is handwritten in black. Below the portrait, “I see saint” is written. For millions of white Americans, black men are sinners, potential predators who deserve what they get from police officers, prosecutors, judges, and jail and prison officials. For African-Americans, the young man is the opposite: the hope for the future, a person on whom the race depends, a youth seeking education and opportunity in a society that will thwart him in numerous ways. This powerful artwork captures the essence of the entire book.

Another key essay by Renée McDonald Hutchins in “Policing the Black Man” addresses the volatile issue of racial profiling. This is an area where implicit bias against black men is pervasive. She reveals the legal basis for the often laughable justifications for police stopping young black men, including the infamous New York City profiling of “stop and frisk,” where, in 2012, the NYPD stopped more than 700,000 New Yorkers, 85 percent of whom were young black or Latino men. Ninety percent of the stops resulted in the targeted individuals being released after no evidence of wrongdoing was found.

The 1968 Supreme Court case of Terry v. Ohio has been the chief legal source of modern racial profiling. It permitted temporary stops and frisks of civilians even if police lacked probable cause, requiring merely “reasonable suspicion” to justify a police encounter. Although the court did not mention race specifically, it was well understood that it was central to its deeper rationale. “Reasonable suspicion” is regularly used to stop persons who “look like someone who committed a crime or is fleeing the scene,” “someone who is carrying a questionable package or anything else,” or “moving in an unusual manner.” Many young black men are well aware of these “explanations” from police officers.

One of the most compelling and poignant essays in the book is “Boys to Men: The Role of Policing in the Socialization of Black Boys,” by Kristin Henning. She writes perceptively: “Black boys are policed like no one else, not even black men.” Police have shot staggering numbers of young black boys, while juvenile African-Americans are regularly sent to adult prisons. They are routinely targeted in public schools as presumptive criminals and targeted by police stationed in the schools themselves. Frequently, through security cameras, metal detectors and other surveillance tactics, black boys are subject to arrest for minor offenses that in past years would have resulted in minimal school discipline.

These arrests in turn create criminal records that inhibit future employment prospects for young black men and contribute to the “school to prison pipeline,” a grim reality that intensifies American racial disparities. This is an especially pernicious feature of policing the black man. Moreover, it exacerbates the widespread ill will against police in African-American communities across the nation, fostering the long-standing racial divide that has existed in America since its inception.

Other essays address various key features of the problematic practices of American law enforcement officials. Davis, for example, writes about the impact of prosecutorial discretion. The charging decisions of law enforcement officials, plea bargaining determinations, and sentence recommendations have a huge—and racist—impact on the lives of black men in the United States. These discriminatory acts contribute to the racial disparity in the criminal justice system as a whole.

Likewise, few elected prosecutors in America are African-American. Ronald Wright’s essay reveals how contemporary election law discourages prosecutors who reflect the views of black citizens. Gerrymandering, the suppression of African-American voters, and public apathy combine to ensure that incumbent prosecutors, many of whom make racially discriminatory decisions regularly, remain in office for long periods of time.

Grand juries too play a crucial role in the overall racism against black men. Roger Fairfax’s essay persuasively demonstrates how prosecutors and police work hand in hand. Prosecutors largely control grand jury proceedings and have little incentive to seek criminal indictments against police officers with whom they work and on whom they rely for evidence. The highly publicized cases of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York; and Tamir Rice in Cleveland show prosecutorial unwillingness to indict their police killers.

A valuable feature of this book is its specific recommendations for change and improvement. Some of the conflicts between African-Americans and police can be addressed, for example, with training programs that teach officers to treat community residents with dignity and respect. Much more rigorous training—that encourages police to recognize their implicit racial biases and assumptions—can go a long way in dissipating distrust, and engendering cooperation rather than conflict between black people and the police who are ostensibly assigned to protect them.

Moreover, programs that train police and other law enforcement officials to enhance their knowledge of adolescent development could dissipate tensions in schools and on the streets. Some communities have launched such programs successfully, with emphasis on youth culture, coping skills, and the vital differences between normal adolescent behavior and criminal conduct. These programs also teach strategies to create safe and respectful encounters between minority youth and police. A critical reform would be to reduce or eliminate cops in schools. Police should be called to campus only in the event of serious criminality or disruption.

Finally, legal changes are essential if relations between African-American communities and law enforcement officials are to improve. As Hutchins suggested in her review of the various racist cases that the Supreme Court has handed down over the past several decades, “It is time to rethink those rules.” Alas, with the present highly conservative Supreme Court, this is a dubious possibility.

The suggestions and policies in “Policing the Black Man” are not trivial. They can have a huge impact on millions of people and they can save human lives. They should be pursued with all due vigor.

But like all liberal reforms, they cannot address the structural and institutional racism that has bedeviled America since its origins as a slave colony. The late Derrick Bell, one of the originators of Critical Race Theory, warned in “Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism,” that black people would never gain full equality in America. The intractable racism in this country means, regrettably, that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream remains unfulfilled. Still, efforts like Davis’ collection move us forward, however slowly and incrementally.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten