Israel’s Stall-Forever ‘Peace’ Plan

Despite boosting the idea of Mideast peace, President Trump shields Israel in its resistance to a workable agreement with the Palestinians, as ex-CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar explained in a Sept. 19 speech.

President Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, whom the President has entrusted with, among many other things, searching for an Israeli-Palestinian peace, said regarding that task: “We don’t want a history lesson. How does that help us get peace? Let’s not focus on that. We’ve read enough books.”

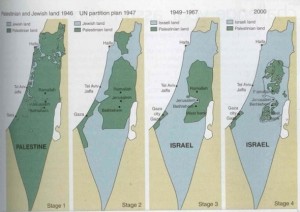

Controversial maps showing the shrinking territory available to the Palestinians. Hardline Israelis insist that there are no Palestinian people, that all the land belongs to Israel and that it therefore inaccurate to show any “Palestinian lands.”

He’s wrong. Without taking into account the history of this conflict, one will never understand it adequately, much less be able to identify formulas that will furnish the necessary respect for, and meet the minimum needs of, both sides.

One could go way back, but let us instead skip to the point in history when war-exhausted Britain, responsible for administering the mandate of Palestine, was facing increasing violence from the contending communities of, on one hand, Arabs who had lived in Palestine for centuries, and on the other hand, Zionists who had begun to settle there over the previous few decades.

Britain dumped the problem into the lap of the United Nations, where the General Assembly approved in 1947 a partition plan for Palestine that would create two new states, one controlled by Jews and one by Arabs. The resolution approving the plan is the one internationally certified birth certificate of the State of Israel.

The population of Palestine at the time was about two-thirds Arab and slightly less than one-third Jewish, with the bulk of the latter representing immigration in the 30 years since the Balfour Declaration. Jews owned less than 7 percent of the land. Under the partition plan, however, the Jewish state would receive 56 percent of Palestine and the Arab state 43 percent, with the remaining one percent being an international zone in Jerusalem. The population of the projected Arab state would be almost entirely Arab, while the Jewish-controlled state would be 45 percent Arab.

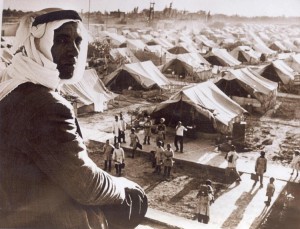

In the war that subsequently broke out, the superior skill and organization of the Zionist forces resulted in conquest of territory beyond the boundaries of the Jewish state in the UN partition plan, such that, at the time of the resulting armistice, the new State of Israel comprised 78 percent of Palestine, with Arabs left in control of 22 percent. Large population displacement occurred during the war. More than 700,000 Palestinian Arabs were expelled from, or fled from, their homes. Between 400 and 600 Palestinian villages were sacked, and Palestinian city life was virtually extinguished. This set of events is what Palestinians came to refer to as the Nakba or catastrophe.

A Single Story

This history is part of a single continuous story of issues that are discussed today as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the so-called peace process. One cannot excise that history. It is an inseparable part of attitudes, emotions, positions, and demands that exist today.

In 1948, some Palestinians, uprooted by Israel’s claims to their lands, relocated to the Jaramana Refugee Camp in Damascus, Syria

In the seven decades since those events of the late 1940s, Israel has grown into the state that is unquestionably the most militarily powerful in the entire Middle East, as well as being in many respects economically powerful. The next big accretion of territory under Israel’s control came from its conquests in the 1967 war, which Israel started with an attack on Egypt amid brinksmanship in the Gulf of Aqaba by Egyptian strongman Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Since that war, Israel has sustained a program of colonization of the conquered territories. Approximately 600,000 Jewish settlers now live outside Israel’s 1967 boundaries, in the West Bank and the eastern part of what Israel defines as Jerusalem.

Palestinian Arabs, in contrast, have remained sunken in a state of weakness and subjugation. For those in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, this status has included, among many other things, having nearly every aspect of life, from building of homes to daily movement to places of livelihood, subjected to the strictures of Israeli military occupation.

For those in the Gaza Strip, the subjugation has taken a different form, in which Israel has maintained control of air, sea, and, with varying degrees of Egyptian regime cooperation, land access to the Strip. With a suffocating blockade in effect much of the time, punctuated by the destruction of periodic military offensives, the Strip is one of the more miserable densely populated pieces of territory in the world.

Changes of Posture

The political and diplomatic positions of both sides have changed significantly over these seven decades. Whatever movement there has been in a direction that would appear to make resolution of the conflict more possible has come in response to some form of force or pressure. This has been true on both the Israeli and Palestinian sides. A detailed accounting of such changes, and of the circumstances that have led to them, can be found in the excellent book by Nathan Thrall, a senior analyst with the International Crisis Group, published this year under the title The Only Language They Understand.

Mahmoud Abbas, President of the State of Palestine, addresses the United Nations General Assembly on Sept. 22, 2016. (UN Photo)

On the Israeli side, for example, Israel’s limited territorial withdrawals from Syria and the Sinai following the 1973 war were in response to the shock of military setbacks and vulnerability that the war exposed, together with pressure from the United States, which had been stung by the Arab oil embargo. Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s acceptance at Camp David in 1978 of a framework for a projected, eventual negotiated resolution of the conflict was in response to pressure applied by Jimmy Carter and Anwar Sadat.

Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir’s agreement in 1991 to attend a peace conference in Madrid was in direct response to pressure from Secretary of State James Baker in the form of a threat to withhold $10 billion in loan guarantees for housing for Russian emigrants — which, by the way, was the last time the United States applied this sort of pressure on Israel.

The record refutes the idea that reassurance to Israel is what is most required to obtain Israel flexibility regarding the conflict with the Palestinians. But this idea persists because it is so politically comfortable here in the United States.

The same sort of dynamic has taken place on the Palestinian side. The positions and postures of the Palestinian mainstream have undergone a great evolution from a refusal to have any dealing with Israel and the waging of armed struggle against it, to explicit recognition of the State of Israel, commitment to a negotiated resolution of the conflict, commitment to two states living side-by-side in peace, and even an acceptance of pre-1967 Israeli military conquests and a reduction of territorial aspirations for a Palestinian state to the 22 percent of land that was left. The background to this evolution has been setback after setback to the Palestinians, including military defeats in Jordan and Lebanon, exile to Tunisia, and political weakness that is most apparent right here in the United States.

An Asymmetrical Conflict

While the two sides have exhibited similar histories regarding the relationship between pressure and flexibility, we are left with a huge asymmetry. There is an enormous difference in strength, obviously militarily but also economically and in terms of political leverage in the United States.

An Israeli strike caused a huge explosion in a residential area in Gaza during the Israeli assault on Gaza in 2008-2009. (Photo credit: Al Jazeera)

There has been a large difference in physical and human consequences. Far more Palestinians than Israelis have died in this conflict. Even going back to the Arab riots in Palestine in the 1930s, the ratio of Arabs to Jews killed was about ten-to-one. The discrepancy has been even greater in more recent conflict. During Operation Protective Edge, the Israeli military operation in the Gaza Strip in 2014, 2,100 Palestinians were killed, about two-thirds of whom were civilians. Israeli deaths from all causes totaled 72, all but six of whom were soldiers. The ratio in the last previous war in Gaza, in 2008-2009, was similar: 14 Israelis killed; over 1,400 Palestinians killed.

The asymmetry is also one between an occupier and the occupied. This seems to get overlooked in mentions of whether Palestinian leaders want a negotiated settlement. For the overwhelming majority of Palestinians, a negotiated two-state solution would be better than what they have now, and the overwhelming majority of Palestinians realize that it would be. They also realize that an agreement negotiated with Israel is the only way a two-state solution would ever be reached.

Conditions that Palestinian leaders have sometimes attached to negotiations should not be that hard to understand. A freeze on more construction of Israeli settlements is understandable because such construction obviously narrows the negotiating space for any peace agreement, and because nobody’s patience is unlimited for something called a peace process to be dragged out endlessly while more such facts on the ground continue to be established unilaterally, making a two-state solution ever harder to achieve.

Resistance to acceding to Israeli demands about calling Israel a “Jewish state” reflects how this demand was never made of Egypt or Jordan when they made peace treaties with Israel, how such descriptive demands are not part of normal recognition and diplomacy between states, how the PLO long ago explicitly recognized the State of Israel, how acceding to the Israeli demand would be an explicit Palestinian declaration that their Arab brethren within Israel are second-class citizens, and how such accession would be a step toward excusing Israel from accepting any responsibility, even symbolically, for the events of the late 1940s.

The asymmetry extends to how much there is left for either side to concede. Again, it is part of the basic difference between an occupier, who has the power to end an occupation, and the occupied, who does not. For the Palestinians, the story of this conflict, and of the diplomacy surrounding it, has been a tale of successive reductions in what they expect, and what they are expected to expect.

From being what was still the large majority of residents of Palestine even at the time of Israel’s creation, they have seen their prospective home go down to 43 percent of Palestine under the U.N. partition plan, to 22 percent after the warfare of the 1940s. And since the 1967 war, they have seen the 22 percent become not a floor but a ceiling in anything that is talked about as a future Palestinian state. The discourse is about a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of what had been their homeland.

Having been backed to a wall, there is very little room for still more backing up, at least in any way consistent with any Palestinian leader meeting the most basic nationalist aspirations and demand for respect for his people, failing which the leader himself forfeits respect and support.

On the Israeli side, one of the relevant pieces of background is the rightward trend in Israeli politics that has continued ever since Begin’s Likud displaced Labor as Israel’s dominant political party. Some members of Netanyahu’s government have been more direct than he has been in calling for things such as immediate annexation by Israel of most of the West Bank.

Israel and the Status Quo

Another relevant piece of background, consistent with the observation that the only significant movement in the position of either side has come when that side has been under pressure, is that the Israeli government simply does not feel sufficient motivation to end the occupation and reach an agreement with the Palestinians. From that government’s viewpoint, the status quo is tolerable, even comfortable.

Graffiti on the Palestinian side of Israel’s “separation wall” recalls the words of John F. Kennedy in decrying the Berlin Wall with the words in German, “I am a Berliner.” (Photo credit: Marc Venezia)

Israeli has its overwhelming regional military superiority. It has its prosperity; it is among the richest one-fifth of the countries in the world in GDP per capita, according to figures from the International Monetary Fund. As suggested by the previously mentioned casualty figures, the immediate physical and human costs of the conflict itself are sustainable and below levels that would make them a significant political liability for leaders. The ugly aspects of occupation are walled off, literally, and beyond the line of sight of most Israelis, meaning that they do not represent any kind of political imperative to change the status quo.

Sure, there is international criticism, but that is something else that Israeli leaders have long experience living with, deflecting, and even turning to their domestic political advantage as protectors of the nation against what are described as unfair critics and even enemies of Israel.

Most important of all, there is the unquestioning backing of the United States, and the political lock that underlies it. That backing takes the form of $3.8 billion in annual subsidies with no strings attached, no compensatory demands being made about Israeli policy, and a diplomatic posture that makes it news when, as once occurred late in the Obama administration, the United States merely abstained on, rather than vetoing, as it repeatedly has done, a U.N. Security Council resolution expressing the critical view that the overwhelming majority of the international community has of Israel’s colonization project in the territories.

Weigh all this against what the Israeli government would face internally if it were to move to end the occupation and help to create a Palestinian state. This would immediately create a severe domestic political crisis within the dominant political right, featuring the resistance of a settler population that now constitutes about a tenth of Israel’s entire Jewish population. It is easy to see why the current government is not attracted to a change of its current course.

It has been observed, correctly, that of three major possible attributes of the current, and future, State of Israel — namely, being Jewish, being democratic, and being in control of all the land between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River — Israel can be any two of those things, but it is impossible for it to be all three. It is impossible because of demographic facts about the peoples who live in that land.

Israeli leaders in power do not usually address that trilemma explicitly and publicly, but occasionally we get a more direct glimpse of the priorities. The Israeli minister of justice, Ayelet Shaked, has made clear she considers the democracy part to be subordinate to the Jewishness part. She has said that it was “not primarily Roman law or the democratic tradition of the Athenian polis that shaped and forged the modern democratic tradition in Europe or the United States, but Jewish tradition — joined, of course, by other traditions. It is precisely when we wish to promote advanced processes of democratization in Israel that we must deepen its Jewish identity.”

As for the role of civil and political rights in general, Shaked says, “Zionism should not – and I’m saying here that it will not – bow its head to a system of individual rights interpreted in a universal manner.”

Obsolete Transitional Arrangements

Meanwhile, on the Palestinian side, political dysfunction persists that is partly a legacy of failed peace process efforts of the past. The leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, which is the recognized interlocutor for peace negotiations, is Mahmoud Abbas, who gets more attention for his other role as head of the Palestinian Authority.

President Jimmy Carter signing the Camp David peace agreement with Egypt’s Anwar Sadat and Israel’s Menachem Begin.

The P.A. was established under the Oslo process in the 1990s to be only a transitional mechanism. It was supposed to yield to something more permanent, like a real Palestinian state, in five or so years. The P.A. long ago passed its sell-by date. Many Palestinians now regard it, with good reason, as mostly an administrative auxiliary to the Israeli occupation. Stasis has set in. Abbas is now in the 13th year of what was supposed to have been a four-year term as P.A. president.

The P.A., and the Fatah-dominated PLO, also do not represent all of the Palestinian body politic. They do not represent refugees, and they do not represent the stream of opinion embodied in Hamas, which won the last free and fair Palestinian parliamentary election, has made clear it is prepared to live in peace in a Palestinian state side-by-side with the State of Israel, and has tried to observe the cease-fires negotiated after the last two Gaza wars.

Israel and the United States refused to accept that election result, and Israel has done everything it can to sustain division between Hamas and Abbas’s P.A., such as by withholding tax receipts owed to the Palestinians when the P.A. has made a move to resolve differences with Hamas. We can expect the same Israeli reaction to an initiative announced by Hamas this week, in which it says it will dissolve its own administration of Gaza in favor of a new joint administration with the P.A. and participation in fresh Palestinian elections.

Recent internal developments on the Israeli side, and specifically Netanyahu’s legal and political problems stemming from multiple corruption cases, only make matters worse regarding any peace process. The prime minister’s response has been to tie himself ever more closely to the right-wing coalition partners whose support he needs to stay in office. That means more of an inflexible hard line on anything having to do with the Palestinians. Netanyahu recently said to an audience of West Bank settlers, “We are here to stay forever. We will deepen our roots, build, strengthen and settle.”

Many informed observers believe that the two-state solution is dead. I don’t believe it is dead in the sense of technical feasibility. Despite how far the Israeli colonization of the West Bank has gone, it still would be possible to construct a peace agreement along lines that have been well known for quite some time, based on the 1967 borders with mutually agreed upon land swaps, and creative ways to deal with sticky issues such as right of return and control of holy places in Jerusalem.

But what the pessimistic observers accurately note, besides the ever-narrowing bargaining space from construction of additional facts on the ground, is how much of the edifice on which the so-called peace process is based has been regarded by one side as a basis for avoiding an ultimate peace agreement rather than building one. The Oslo formula that created the P.A. was based, on Israeli insistence, on the 1978 Camp David framework agreement, which in turn was based on an autonomy plan from Begin that was designed not to establish Palestinian self-determination but to prevent it.

This has been a matter of peace processing indefinitely while the side in control has created still more facts on the ground. Begin’s successor Yitzhak Shamir was quite candid about this when he said, ”I would have carried on autonomy talks for ten years, and meanwhile we would have reached half a million people in Judea and Samaria.”

Trump’s Posture

And now we have, in the country with the greatest potential outside leverage over all this, the Trump administration. Donald Trump said some things early in his campaign about being even-handed, but then he made his peace with (the intensely pro-Israeli billionaire) Sheldon Adelson, and from the time he spoke later during the campaign to AIPAC, most of what he has said and done on this issue would have easily passed muster in the Israeli prime minister’s office.

President Trump meets with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in New York on Sept. 18, 2017. (Screenshot from Whitehouse.gov)

His son-in-law the envoy comes from a family with connections to West Bank settlements. Trump’s bankruptcy lawyer, whom he has appointed as ambassador to Israel, has direct personal involvement in aiding a West Bank settlement, has likened liberal, pro-peace American Jews to Nazi collaborators, and recently departed from a long-established U.S. diplomatic lexicon by referring to the “alleged occupation”.

Trump has backed away from the two-state solution, which had been the explicit U.S. objective of the previous couple of administrations, Republican and Democratic, and the implicit objective of the couple of administrations before that, Republican and Democratic. In an extraordinary statement, the State Department spokeswoman recently said that to recommit to the two-state solution would constitute “bias.”

As former U.S. Ambassador to Israel Daniel Kurtzer commented in an op-ed, “her words indicate that the Trump administration itself is extremely biased — in favor of hardliners in … Netanyahu’s coalition who want the United States and Israel to abandon the two- state outcome.”

Those hardliners, and the Trump administration, have recently been looking to what is referred to as the “outside-in” concept — the idea the other Arab states will lean on the Palestinians to accept something less than a real state. But if the key to a peace settlement rested with those other Arab states, then Israel could pick up off the table what has been on the table for 15 years: the Arab League peace initiative, which offers full recognition of, and peace with, Israel by all Arab states and a formal declaration that the Arab-Israeli conflict is over, in return for an end to the occupation and establishment of a Palestinian state.

Genuine peace with the region still requires genuine peace with the Palestinians. Neither the Saudis nor other Arab leaders will sign off on bantustans for their Arab brethren in Palestine.

And so the prospect is for this long-running conflict to continue to run, with all of the substantial human, economic, political, and diplomatic costs that the conflict has entailed. Only a two-state solution can realize the national aspirations both of Jewish Israelis and Palestinian Arabs. Without it, Israel will continue not to have recognized borders, not be at peace with its region, and not be anything other than a heavily militarized state and in many ways a pariah state. It will, as Netanyahu has put it, “live forever by the sword.”

Without a two-state solution, Palestinians will continue to endure their all-too-well documented subjugation and suffering, and will exhibit the severe discontent that breeds extremism.

And without such a solution, the United States will continue to be associated with acceptance of this festering and undesirable situation, will be seen as condoning and supporting what the overwhelming majority of the world considers a gross injustice, and will continue to be the target of violent extremists who, again and again, cite this issue as one of their principal motivators and rallying cries.

(Pillar was speaking to the Worcester, Massachusetts, World Affairs Council.)

Paul R. Pillar, in his 28 years at the Central Intelligence Agency, rose to be one of the agency’s top analysts. He is author most recently of Why America Misunderstands the World. (This article first appeared as a blog post at The National Interest’s Web site. Reprinted with author’s permission.)

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten