JPMorgan Concludes The World Is Drowning In Too Much Debt For Stocks To Go Down Again

Earlier this week, JPM's quant Nicholas Panigirtzoglou spotted an ominous signal for equities: similar to what happened in mid-2018 (just before the Fed's overtightening sent stocks tumbling into a mini bear market in Q4 2018), and then again in the late summer of 2019, when the "break" in the repo market (which incidentally was caused by JPMorgan) forced the Fed to launch "Not QE", last week the front end of the US Treasury curve (which is a far better signal of financial stress than the long-end which now is mostly a function of global QE) represented by the 1m OIS 2Y-1Y forward spread and which to the JPM quant "is a better signal of policy expectations", once again inverted, sending an ominous alert signal across asset classes.

As the JPM quant continued, "while the spread between the 1- and 2-year forward points of the US OIS curve in Figure 2 had improved rapidly and turned significantly positive after the dramatic policy response to the virus crisis last March, it has been slipping over the past couple of months and turned negative last week. It printed -3bp negative on Monday, June 29th."

To JPM, this suggests that rate markets are signaling the need for further monetary and/or fiscal policy stimulus across DM economies. And, logically, if the Fed turns a deaf ear to this latest extortion attempt by market, and additional stimulus is not delivered, then the inversion at the front end could worsen, "eventually becoming a more problematic signal for equity and risky markets going forward."

In other words, having injected over $3 trillion in liquidity in the past three months, JPM argues that this is nowhere near enough, and incidentally, the House of Morgan is not alone: after all this is precisely the same argument that Goldman made in mid-May when the bank "spotted a huge problem for the Fed", namely that the Fed will need to monetize much more debt - about $1.6 trillion more - than it currently envisions in order to avoid a disorderly surge in Treasury yields.

And while it probably wasn't the intention of JPM to spook clients and other investors, it appears that it did just that, because just two days after Panigirtzoglou published his ominous warning, the Greek JPMorganite is back with a report whose purpose is simple: to talk back all of the anxiety sparked by his observation that the front-end has inverted.

The argument is even simpler: there is too much debt, and too much liquidity, for stocks to drop. No really...

Yup: any other time the breakneck increase in public and private debt would have been a 140 dB warning claxon going off 24/7, but now - in a time of helicopter money and MMT - it is precisely what the central planning doctor ordered to make sure that stocks never again suffer even a modest pullback, and paradoxically, that's precisely what Panigirtozglou is pitching in his latest note, which ironically, comes just two days after the same JPM quant warned that the Fed had not done enough.

Well, looks like he got the tap on the shoulder to make it clear that the Fed has done whatever it can.

For those who care about this bizarre, unexpected and total U-turn, we have reproduced it below in its entirety, even though it could be summarized much better in just a few short words.

Similar to the Lehman crisis, the virus crisis is causing a step increase in the amount of debt in the financial system. The need to replace lost income is inducing more debt creation by both the private sector, i.e. households and non-financial corporations, but also by the government sector, which, via stimulus programs, aims at smoothing private sector's income disruption.

According to the IMF, the global fiscal support in response to the virus crisis stands at around $9tr or 12% of global GDP ($76tr at end-2019 exchange rates), half of which is via direct budget support and the other half in the form of additional public sector loans and equity injections, guarantees, and other quasifiscal operations. This implies that, at a global level, after also factoring in a decline to GDP by 5% this year, the government debt-to-GDP ratio would increase from around 88% at the end of 2019 to 105% by the end of this year.

Private sector indebtedness is also seeing a sharp increase. Bank lending to the private sector and net corporate bond issuance have together amounted to $5tr in the first half of the year. Assuming a further $2tr into the second half would raise private sector indebtedness by another 9% of GDP or so. At a global level, after also factoring in a decline to GDP by 5% this year, the private sector, i.e. household and non-financial corporate sector, debt to GDP ratio would increase from around 155% at the end of 2019 to 173% by the end of this year.

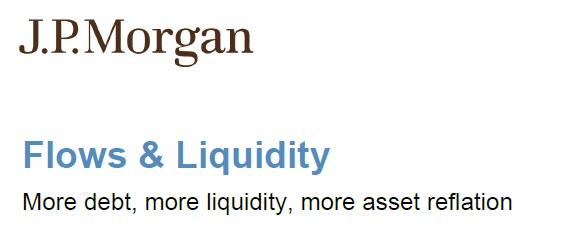

In all, adding $16tr of additional debt this year would raise the total debt in the world, private and government debt, to a new record high $200tr by the end of this year. Factoring in a decline to GDP by 5% this year, would raise the total debt to GDP ratio for the world as a whole by around 35 percentage points, from 243% at the end of 2019 to 278% by the end of this year. This 35% of GDP increase in global indebtedness is even bigger than the 20% of GDP increase seen in the year after the Lehman crisis.

There are three main implications from the big increase in global indebtedness.

- First, the private sector would likely be inclined to save more in the future, sustaining the persistently high savings rates seen in the decade after the Lehman crisis. In turn, persistently high private sector savings rates would keep economic growth and inflation low and make it even more difficult for debt levels to decline vs. incomes in the future.

- Second, very accommodative central bank policy policies and low interest rates are likely to continue for a very long time to make it possible for both the government sector and the private sector to sustain their much higher debt levels. Indeed, Figure 1 shows that there has been an inverse relationship between debt levels and interest rates.

- The third implication is more liquidity. More credit and more monetary stimulus in the form of QE, both imply more liquidity, i.e. extra money supply and cash balances, which in turn would result in more asset reflation.

The rapid increase in debt creation implies a rapid creation of liquidity both directly and indirectly. Bank lending creates money directly, and is how most money is created during normal times. This is because as a bank creates a new loan, it simultaneously creates a new deposit, and the increase in net bank lending in the economy essentially increases deposits by the same amount.

While bond issuance does not create deposits directly in the same way bank lending does, when QE purchases by central banks absorb (mostly government) bonds from the portfolios of private non-bank investors, such as pension funds, asset managers and insurance companies, which has been the case with QE so far, liquidity is being created.

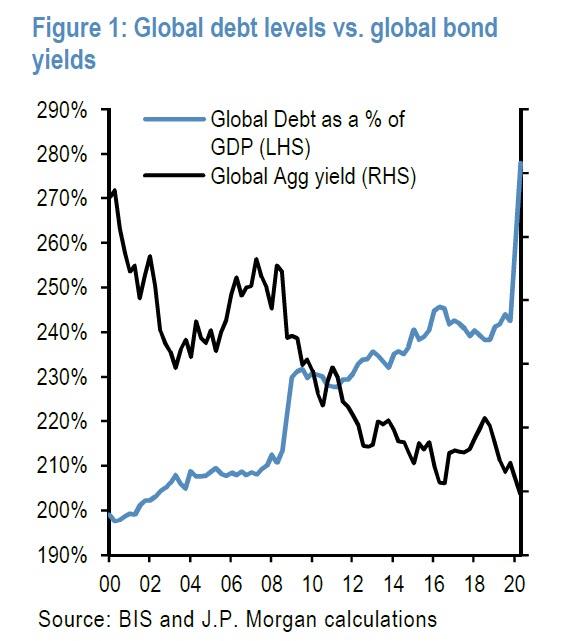

This means that debt creation should create a similar amount of liquidity. Indeed, there has already been a significant expansion of global M2 as depicted in Figure 2, which converts M2 to US dollars using constant FX rates to abstract from the influence of currency fluctuations. It shows a sharp increase in M2 from the beginning of the year to end-May of around $6tr ex China or $8tr including China. The amount of liquidity or money creation so far is similar to the magnitude of M2 creation during the financial crisis of 2008/2009, but has occurred much more quickly, in only a few months, as policy makers responded more aggressively to the impact of the pandemic. But given that debt creation and QE will continue to be stronger than normal until 2021, we believe that the total money or liquidity creation could exceed $15tr or more globally by the middle of 2021.

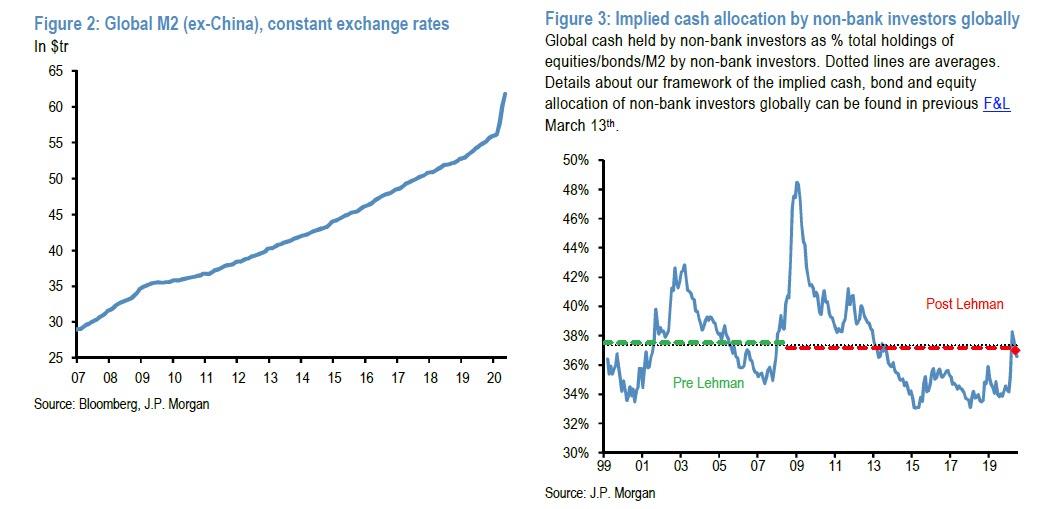

As a result of this liquidity creation, our estimation of the share of cash holdings in global non-bank investors’ portfolios, which rose sharply in March, remains well above pre-pandemic levels despite the nearly 40% rise in global equities that have seen equities retrace three quarters of their March drawdowns. And these elevated cash holdings create a strong background support for non-cash assets such as bonds and equities. But given how low bond yields are at the moment, less than 1% in the Global Agg bond index, we believe that most of this liquidity will eventually be deployed into equities as the need for precautionary savings subsides over time.

And so on. TL/DR: there is just too much debt in the world right now for either interest rates to go up again, or for stocks to go down. And that, being the dumbest yet perhaps most accurate analysis we have read in a while, is how virtually all strategists on Wall Street just became obsolete, because no amount of brilliant analysis will ever again top what is truly the bottom line for a world drowning in debt - the system will continue growing on the back of trillions and trillions in debt, until one everything comes crashing down.

1 opmerking:

Remarks from the Systematic Crises Triggered the Current Pandemic teleconference - Michael Hudson

"Only the banks and financial sector, the elite One Percent, are supported, as in the United States. Ten trillion dollars ’s put into the economy, mainly into the stock and financial markets, the bond market and the real estate market, but not into production.

The Eurozone does not do that. This means that the governments of Europe are not really democratic. Europe is governed by the European Central Bank. It works for its customers, the commercial banks. And the commercial bankers say: “We want to starve the economy of credit, so that we, the commercial bankers, can create the money to lend to our customers, and charge interest and financial fees. Our own financial speculation that all the growth, the surplus that Europe produces, should be turned over to the financial sector.” That’s what the Europeans have voted for. In effect they vote for lower wages, cutbacks in public services and shorter pensions. These living standards are threatened by the way in which the financial dimension of the coronavirus crisis is being managed." [..]

This may seem a crazy way to organize society, but it is how Western civilization has been structured on the basis of protecting creditor rights, not debtor solvency and overall social balance and continuity. Unlike non-Western societies, unlike even China today, credit in Europe and America is privatized. The supply of credit, like money, should be a public utility. Just like public health should be a public utility. Just like roads and communication should be a public utility. Europe has let it be privatized in an aggressive, predatory way. [..]

And that’s what you have in Europe. It’s not a democracy anymore; it’s an oligarchy making itself into the same kind of hereditary aristocracy that occurred in classical antiquity. Many of you hoped that Europe had overthrown the aristocracy after World War I when you did indeed get rid of the kings and royalty. But you opened the way for a new kind of oligarchy turning itself into a hereditary aristocracy, that of finance. That’s the task before you to solve. The only thing I can say is that, perhaps, this crisis has indeed catalysed this basic internal contradiction and will create a response that deals with the pandemic by cancelling debts and de-privatizing the banking sector."

Een reactie posten