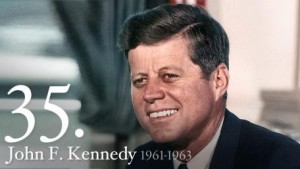

How CBS News Aided the JFK Cover-up

Special Report: With the Warren Report on JFK’s assassination under attack in the mid-1960s, there was a chance to correct the errors and reassess the findings, but CBS News intervened to silence the critics, reports James DiEugenio.

In the mid-1960s, amid growing skepticism about the Warren Commission’s lone-gunman findings on John F. Kennedy’s assassination, there was a struggle inside CBS News about whether to allow the critics a fair public hearing at the then-dominant news network. Some CBS producers pushed for a debate between believers and doubters and one even submitted a proposal to put the Warren Report “on trial,” according to internal CBS documents.

But CBS executives, who were staunch supporters of the Warren findings and had personal ties to some commission members, spiked those plans and instead insisted on presenting a defense of the lone-gunman theory while dismissing doubts as baseless conspiracy theories, the documents show.

Though it may be hard to remember – amid today’s proliferation of cable channels and Internet sites – CBS, along with NBC and ABC, wielded powerful control over what the American people got to see, hear and take seriously in the 1960s. By slapping down any criticism of the Warren Commission, CBS executives effectively prevented the case surrounding the 1963 assassination of President Kennedy from ever receiving the full airing that it deserved.

Beyond that historical significance, the internal documents – compiled by onetime CBS News assistant producer Roger Feinman – show how a major mainstream news organization green-lights one approach to presenting sensitive national security news while blocking another. The documents also shed light on how senior news executives, who have bought into one interpretation of the facts, are highly resistant to revisit the evidence.

Buying In

CBS News jumped onboard the blue-ribbon Warren Commission’s findings as soon as they were released on Sept. 27, 1964, just over 10 months after President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, on Nov. 22, 1963. In a special report, CBS and its anchor Walter Cronkite preempted regular programming and, with the assistance of reporter Dan Rather, devoted two commercial-free hours to endorsing the main tenets of that report.

However, despite Cronkite and Rather giving the Warren Report their public embrace, other people, who were not in the employ of the mainstream media, examined critically the report and the accompanying 26 volumes. Some of these citizens were lawyers and others were professors, the likes of Vincent Salandria and Richard Popkin. They came to the conclusion that CBS had been less than rigorous in its examination.

By 1967, the analyses challenging the Warren Report’s conclusions had become widespread, including popular books by Edward Epstein, Mark Lane, Sylvia Meagher and Josiah Thompson. Thompson’s book, Six Seconds in Dallas, was excerpted and placed on the cover of the wide-circulation magazine Saturday Evening Post. Lane was appearing on talk shows. Prosecutor Jim Garrison had announced a reopening of the JFK case in New Orleans. The dam was threatening to break.

The doubts about the Warren Report had even spread into the ranks at CBS News, where correspondent Daniel Schorr and Washington Bureau chief Bill Small recommended a fair and critical look at the report’s methodology and findings. Top prime-time producer Les Midgley later joined the effort.

CBS News vice president Gordon Manning sent the proposal on to CBS News president Richard Salant in August 1966, but it was declined. Manning tried again in October, suggesting an open debate between the critics of the Warren Report and former Commission counsels, moderated by a law school dean or the president of the American Bar Association. The idea was to give the two sides a chance to make their best points before the viewing public.

Zapruder Evidence

One month after Manning’s debate proposal, Life Magazine published a front-page story in which the Warren Commission’s verdict was questioned by photographic evidence from the Zapruder film (which the magazine owned). Life also interviewed Texas Gov. John Connally who disagreed that he and Kennedy had been hit by the same shot, a claim that undercut the “single bullet theory” at the heart of the Warren Report.

A frame from the Zapruder film capturing the first shot that struck President John F. Kennedy on Nov. 22, 1963. Texas Gov. John Connally, who was also wounded, is seated in front of Kennedy..

Without the assertion that a single bullet inflicted multiple wounds on Kennedy and Connally, who was riding in front of the President, the commission’s verdict collapses. The magazine story ended with a call to reopen the case. Indeed, Life had put together a small journalistic team to do its own internal investigation.

A few days after this issue appeared, Manning again pressed for a CBS special. This time he suggested the title “The Trial of Lee Harvey Oswald,” with a panel of law school deans reviewing the evidence against Oswald in a mock trial, including evidence that the Warren Commission had not included. In other words, there would be a chance for American “jurors” to weigh the evidence that might have been presented against Oswald if he had lived and to make a judgment on his guilt. Again, this approach offered the potential for a reasonably balanced examination of the Kennedy assassination.

At this point, Manning was joined by producer Midgley, who had produced the two-hour 1964 CBS special. Midgley’s suggestion differed from Manning’s in that he wanted to title the show “The Warren Report on Trial.” Midgley suggested a three-night, three-hour series with one night given over to the commission defenders, one night including all the witnesses that the commission overlooked or discounted, and the last night including a verdict produced by legal experts. But the title itself suggested a level of skepticism that had not been part of the earlier proposals.

The Higher-ups Intervene

However, then CBS senior executives began to intervene. On Dec. 1, 1966, Salant wrote a memo to John Schneider, president of CBS Broadcast Group, telling him that he might refer the proposal to the CBS News Executive Committee (CNEC). According to information that a former CBS assistant producer Roger Feinman obtained during a legal hearing against CBS, plus secondary sources, CNEC was a secretive group that was created in the wake of Edward R. Murrow’s departure from CBS.

Murrow was a true investigative reporter who became famous through his reports on Sen. Joe McCarthy’s abuses and the mistreatment of migrant farm workers. The upper management at CBS did not like the controversies that these reports generated among influential segments of the American power structure. There was a perceived need to tamp down on such wide-ranging and independent-minded investigations. After all, the CBS executives were part of that power structure.

CBS News president Salant epitomized that blurring of high-level corporate journalism and America’s ruling class. Salant had gone to Exeter Academy, Harvard, and then Harvard Law School. He was handpicked from the network’s Manhattan legal firm by CBS President Frank Stanton to join his management team.

During World War II, Stanton had worked in the Office of War Information, the psychological warfare branch. In the 1950s, President Dwight Eisenhower had appointed Stanton to a small committee to organize how the United States would survive a nuclear attack. From 1961-67, Stanton was chairman of Rand Corporation, a CIA-associated think tank.

The other two members of CNEC were Sig Mickelson, who had preceded Salant as CBS News president and then became a director of Time-Life Broadcasting, and CBS founder Bill Paley, who had also served in the World War II psy-war branch of the Office of War Information and – after the war – let CIA Director Allen Dulles have the spy agency informally debrief CBS overseas correspondents.

When Salant turned the Warren Commission issue over to CNEC, the prospects for any objective or skeptical treatment of the JFK case faded. “The establishment of CNEC effectively curtailed the news division’s independence,” Feinman later wrote about his discoveries.

Further, Salant had no journalistic experience and was in almost daily communication with Stanton, whose background was in government propaganda.

Scaling Back

The day after Salant informed CNEC about the proposed JFK assassination special, Salant told CBS News vice president Manning that he was wavering on the mock trial concept. Salant’s next move was even more ominous. He sent both Manning and prime-time news producer Midgley to California to talk to two lawyers about the project.

One of the attorneys was Edwin Huddleson, a partner in the San Francisco firm of Cooley, Godward, Castro and Huddleson. Huddleson attended Harvard Law with Salant and, like Stanton, was on the board of the Rand Corporation. The other lawyer was Bayless Manning, Dean of Stanford Law School. They told the CBS representatives that they were against the network undertaking the project on the grounds of “the national interest” and because of the topic’s “political implications.”

CBS News vice president Manning reported that both attorneys advised the CBS team to ignore the critics of the Warren Commission or to appoint a special panel to critique their books, in other words, to put the critics on trial. Huddleson also steered the CBS team to cooperative scientists who would counter the critics.

On his return to CBS headquarters, Manning saw the writing on the wall. He knew what his CBS superiors really wanted and it wasn’t some no-holds-barred examination of the Warren Commission’s flaws. So, he suggested a new title for the series, “In Defense of the Warren Report,” and wrote that CBS should dismiss “the inane, irresponsible, and hare-brained challenges of Mark Lane and others of that stripe.”

Out on a Limb

Manning’s defection from an open-minded treatment of the evidence to a one-sided Warren Commission defense left producer Midgley out on a limb. However, unaware of what Salant was up to, on Dec. 14, 1966, Midgley circulated a memo about how he planned on approaching the Warren Report project. He proposed running experiments that were more scientific than “the ridiculous ones run by the FBI.” He still wanted a mock trial to show how the operation of the Commission was “almost incredibly inadequate.”

In response, Salant circulated an anonymous, undated, paragraph-by-paragraph rebuttal to Midgley’s plan, which Feinman’s later investigation determined was written by Warren Commissioner John McCloy, then Chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations and the father of Ellen McCloy, Salant’s administrative assistant.

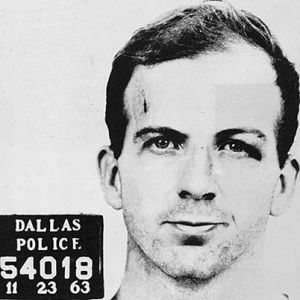

In this memo, McCloy wrote that “the chief evidence that Oswald acted alone and shot alone is not to be found in the ballistics and pathology of the assassination, but in the fact of his loner life.” As many Warren Commission critics have noted, it was this approach – discounting or ignoring the medical and ballistics evidence, but concentrating on Oswald’s alleged social life – that was a fatal flaw of the Warren Report.

Despite the familial conflict of interest, Ellen McCloy was added to the distribution list for almost all memos related to the Kennedy assassination project and thus could serve as a secret back-channel between CBS and her father.

A Stonewall Defense

Clearly, the original idea for a fresh examination of the Warren Commission and the evidence that had arisen since its report was published in 1964 had been turned on its head. The CBS brass wanted a defense, not a critique.

Salant asked producer Midgley, “Is the question whether Oswald was a CIA or FBI informant really so substantial that we have to deal with it?” Midgley, increasingly alone out on the limb, replied, “Yes, we must treat it.”

As the initial plan for a forthright examination of the Warren Commission’s shortcomings was transformed into a stonewall defense of the official findings, there was still the problem of Midgley, the last holdout. But eventually his head was turned, too.

While the four-night special was in production, Midgley became engaged to Betty Furness, a former actress-turned-television-commercial pitchwoman whom President Lyndon Johnson appointed as his special assistant for consumer affairs, even though her only experience in the field had been selling Westinghouse appliances for 11 years on television. She was sworn in on April 27, 1967, which was about two months before the CBS production aired. Two weeks after it was broadcast, Midgley and Furness were married.

As Kai Bird’s biography of McCloy, The Chairman, makes clear, Johnson and McCloy were friends and colleagues. But there is another point about how Midgley was convinced to go along with McCloy’s view of the Warren Commission. Around the same time he married Furness, he received a significant promotion, elevated to executive editor of the network’s flagship news program, “The CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite.” This made him, in essence, the top news editor at CBS, a decision that required the consultation and approval of Salant, Cronkite and Stanton – and very likely the CNEC.

So, instead of a serious investigation into the murder of President Kennedy – at a time when there was the possibility of effective national action to get at the truth – CBS News delivered a stalwart defense of the Warren Commission’s conclusions and heaped ridicule on anyone who dared question those findings.

Shaping that approach was not only the influence of Warren Commission member John McCloy, an icon of the Establishment, but the carrots and sticks applied to senior CBS producers, such as Gordon Manning and Les Midgley, who initially favored a more skeptical approach but were convinced to abandon that goal.

Curious Consultants

Once McCloy was brought onboard, the complexion of CBS’s treatment of the JFK assassination changed. CBS hired consultants who were rabidly pro-Warren Report to appear as on-air experts while others would be hidden in the shadows. In addition to the clandestine role of McCloy, some of these consultants included Dallas police officer Gerald Hill, physicist Luis Alvarez and reporter Lawrence Schiller.

Officer Hill was just about everywhere in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963. He was at the Texas School Book Depository where Oswald worked and allegedly shot the President from the sixth floor; Hill was at the murder scene of Officer J. D Tippit, who was allegedly shot by Oswald after he fled Dealey Plaza; and he was at the Texas Theater where Oswald was arrested.

Hill appeared in the CBS 1967 program show as a speaker. But Roger Feinman found out that Hill also was paid for six weeks work on the show as a consultant. During his consulting, Hill revealed that the police did a “fast frisk” on Oswald while in the theater. They found nothing in his pockets at the time, which begs the question of where the bullets the police said they found in his pockets later at the station came from. That question did not arise during the program since CBS never revealed the contradiction. (Click here and go to page 20 of the transcript.)

Physicist Luis Alvarez, who had a served as an adviser to the CIA and to the U.S. military in the Vietnam War, spent a considerable amount of time lending his name to articles supporting the Warren Report and conducting questionable experiments supporting its findings. As demonstrated by authors Josiah Thompson (in 2013) and Gary Aguilar (in 2014), Alvarez misrepresented some data in some of his JFK experiments. (Click here and go to the 37:00 mark for Aguilar’s presentation.)

Making Fun

The same year of the 1967 CBS broadcast, reporter Lawrence Schiller had co-written a book entitled The Scavengers and Critics of the Warren Report, a picaresque journey through America where Schiller interviewed some of the prominent – and not so prominent – critics of the report and caricatured them hideously.

Secretly, he had been an informant for the FBI for many years keeping an eye on people like Mark Lane and Jim Garrison, whom Schiller attacked despite discovering witnesses who attested to Garrison’s suspect Clay Shaw using the alias Clay Bertrand, a key point in Garrison’s case. The relevant documents were not declassified until the Assassination Records and Reviews Board was set up in the 1990s. [See Destiny Betrayed, Second Edition, by James DiEugenio, p. 388]

This cast of consultants – along with McCloy – influenced the direction of the 1967 CBS Special Report. The last thing these consultants wanted to do was to expose the faulty methodology that the Warren Commission had employed.

As in 1964, Walter Cronkite manned the anchor desk and Dan Rather was the main field reporter. Again, CBS could find no serious problems with the Warren Report. The critics were misguided, CBS said. After all, Cronkite and Rather had done a seven-month inquiry.

‘Unimpeachable Credentials’

In the broadcast, Cronkite names the men on the Warren Commission as their pictures appear on screen. He calls them “men of unimpeachable credentials” but left out the fact that President Kennedy fired Commissioner Allen Dulles from the CIA in 1961 for lying to him about the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.

When Cronkite got to the crux of the program, he said the Warren Commission assured the American people that they would get the most searching investigation in history. Then, Cronkite showed books and articles critical of the commission and mentioned that polls showed that a majority of Americans had lost faith in the Warren Report.

At that point, the network special revealed its purpose, to discredit the critics and reassure the public that these people could not be trusted.

Cronkite went through a list of points that the critics had raised, including key issues such as how many shots were fired and how quickly they could be discharged from the suspect rifle. On each point, Cronkite took the Warren Commission’s side, saying Oswald fired three shots from the sixth floor with the rifle attributed to him by the Warren Commission. Two of three were direct hits – to Kennedy’s head and shoulder area – within six seconds.

One way that CBS fortified the case for just three shots was Alvarez’s examination of the Zapruder film, Abraham Zapruder’s 26-second film of Kennedy’s assassination taken from Zapruder’s position in Dealey Plaza, a sequence that CBS did not actually show.

Alvarez proclaimed that by doing something called a “jiggle analysis,” he computed that there were three shots fired during the film. What the jiggle amounted to was a blurring of frames on the film (presumably because Zapruder would have flinched at the sound of gunshots).

Dan Rather took this Alvarez idea to Charles Wyckoff, a professional photo analyst in Massachusetts. Agreeing with Alvarez, at least on camera, Wyckoff mapped out the three areas of “jiggles.” The Alvarez/Wyckoff formula was simple: three jiggles, three shots.

But as Feinman found out through his legal discovery and hearings, there was a big problem with this declaration. Wyckoff had actually discovered four jiggles, not three. Therefore, by the Alvarez formula, there was a second gunman and thus a conspiracy.

President John F. Kennedy’s motorcade enters Dealey Plaza in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963, shortly before his assassination. (Zapruder film)

Wyckoff’s on-camera discussion of this was cut out and not included in the official transcript. But it is interesting to note just how committed Wyckoff was to the CBS agenda, for he tried to explain the fourth jiggle as Zapruder’s reaction to a siren. As Feinman noted, how Wyckoff could determine this from a silent 8 mm film is puzzling. But the point is, this analysis did not support the commission. It undermined the Warren Report and was left on the cutting-room floor.

There were other problems with the Alverez-Wyckoff “jiggle” theory, since the first jiggle was at around Zapruder frame 190, or a few frames previous to that, which would have meant that Oswald would have had to be firing through the branches of an oak tree, which is why the Warren Commission moved this shot up to frame 210.

But CBS left itself an out, claiming there was an opening in the tree branches at frame 186 and Oswald could have fired at that point. But that is patently ridiculous, since the opening at frame 186 lasted for 1/18th of a second. To say that Oswald anticipated a less than split-second opening, and then steeled himself in a flash to align the target, aim, and fire is all stuff from the realm of comic books super heroes. Yet, in its blind obeisance to the Warren Report, this is what CBS had reduced itself to.

Another way that CBS tried to bolster the Warren Report was to have Wyckoff purchase other Bell and Howell movie cameras (since CBS was not allowed to handle the actual Zapruder camera.) After winding up these cameras, CBS hypothesized that Zapruder’s camera might have been running a little slow, giving Oswald a longer firing sequence.

The problem with this theory, however, was that both the FBI and Bell and Howell had tested the speed of Zapruder’s actual camera. Even Dick Salant commented that this was “logically inconclusive and unpersuasive,” but it stayed in the program.

The Shot Sequence

But why did Rather and Wyckoff have to stoop this low? The answer is because of the results of their rifle firing tests. As the critics of the Warren Report had pointed out, the commission had used two tests to see if Oswald could have gotten off three shots in the allotted 5.6 seconds indicated by the Zapruder film.

These tests ended up as failing to prove Oswald could have performed this feat of marksmanship. What made it worse is that the commission had used very proficient rifleman to try and duplicate what the commission said Oswald had done. [See Sylvia Meagher, Accessories After the Fact, p. 108]

So CBS tried again. This time they set up a track with a sled on it to simulate the back of Kennedy’s head. They then elevated a firing point to simulate the sixth floor “sniper’s nest,” though there were differences from Dealey Plaza including the oak tree and a rise in the street in the real crime scene. Nevertheless, the CBS experimenters released the target on its sled and had a marksman named Ed Crossman fire his three shots.

Crossman had a considerable reputation in the field, but – even though he was given a week to practice with a version of the Mannlicher Carcano rifle – his results were not up to snuff. According to a report by producer Midgley, Crossman never broke 6.25 seconds (longer than Oswald’s purported 5.6 seconds) and – even with an enlarged target – he got only two of three hits in about 50 percent of his attempts.

Crossman explained that the rifle had a sticky bolt action and a faulty viewing scope. But what the professional sniper did not know is that the actual rifle in evidence was even harder to work. Crossman said that to perform such a feat on the first time out would require a lot of luck.

However, since that evidence did not fit the show’s agenda, it was discarded, both the test and the comments. To resolve that problem, CBS called in 11 professional marksmen who first went to an indoor firing range and practiced to their heart’s content, though the Warren Commission could find no evidence that Oswald practiced.

The 11 men then took 37 runs at duplicating what Oswald was supposed to have done. There were three instances where two out of three hits were recorded in 5.6 seconds. The best time was achieved by Howard Donahue on his third attempt after his first two attempts were complete failures.

But CBS claimed that the average recorded time was 5.6 seconds, without including the 17 attempts that were thrown out because of mechanical failure. CBS also didn’t tell the public the surviving average was 1.2 hits out of three with an enlarged target.

The truly striking characteristic of these trials was the amount of instances where the shooter could not get any result at all. More often than not, once the clip was loaded, the bolt action jammed. The sniper had to realign the target and fire again. According to the Warren Report, that could not have happened with Oswald.

There is also the anomaly of James Tague, who was struck by one bullet that the Warren Commission said had ricocheted off the curb of a different street, about 260 feet away from the limousine. But how could Oswald have missed by that much if he was so accurate on his other two shots? That was another discrepancy deleted by the CBS editors.

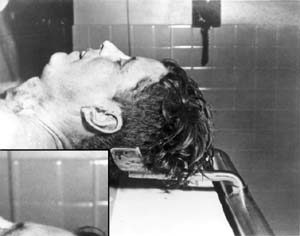

The Autopsy Disputes

CBS also obscured what was said by the two chief medical witnesses after the assassination by Dr. Malcolm Perry from Parkland Hospital in Dallas, where Kennedy was taken after he was hit, and James Humes, the chief pathologist at the autopsy examination at Bethesda Medical Center that evening.

In their research for the series, CBS had discovered a transcript of Dr. Perry’s press conference that the Warren Commission did not have. But CBS camouflaged what Perry said on Nov. 22, 1963, specifically about Kennedy’s anterior neck wound. Perry said it had the appearance to him of being an entrance wound, and he said this three times.

Cronkite tried to characterize the conference as Perry being rushed out to the press and badgered. But that wasn’t true, since the press conference was about two hours after Perry had done a tracheotomy over the front neck wound. The performance of that incision had given Perry the closest and most deliberate look at that wound.

Perry therefore had the time to recover from the pressure of the operation and there was no badgering of Perry. Newsmen were simply asking him questions about the wounds he saw. Perry had the opportunity to answer the questions on his own terms. Again, CBS seemed intent on concealing evidence of a possible second assassin — because Oswald could not have fired at Kennedy from the front.

Commander James Humes, the pathologist, did not want to appear on the program, but was pressured by Attorney General Ramsey Clark, possibly with McCloy’s assistance. As Feinman discovered, the preliminary talks with Humes were done through a friend of his at the church he attended.

There were two things that Humes said in these early discussions that were bracing. First, he said that he recalled an x-ray of the President, which showed a malleable probe connecting the rear back wound with the front neck wound. Second, he said that he had orders not to do a complete autopsy. He would not reveal who gave him these orders, except to say that it was not Robert Kennedy. [Charles Crenshaw, Trauma Room One, p. 182]

The significance of the malleable probe is that, if Humes was correct, the front and back wounds would have come from the same bullet. However, we learned almost 30 years later from the Assassination Records Review Board that other witnesses also saw a malleable probe go through Kennedy’s back, but said the probe did not go through the body since the wounds did not connect. However, x-rays that might confirm the presence of the probe are missing. [DiEugenio, Reclaiming Parkland, pgs. 116-18]

Location of the Wounds

On camera, Humes also said the posterior body wound was at the base of the neck. Dan Rather then showed Humes the drawings made of the wound in the back as depicted by medical illustrator Harold Rydberg for the Warren Commission, also depicting the wound as being in the neck, which Humes agreed with on camera. He added that they had reviewed the photos and referred to measurements and this all indicated the wound was in the neck.

Even for CBS — and Warren Commissioner John McCloy — this must have been surprising since the autopsy photos do not reveal the wound to be at the base of the neck but clearly in the back. (Click here and scroll down.) CBS should have sent its own independent expert to the archive because Humes clearly had a vested interest in seeing his autopsy report bolstered, especially since it was under attack by more than one critic.

The second point that makes Humes’s interview curious is his comments on the Rydberg drawings’ accuracy. These do not coincide with what Rydberg said later, not understanding why he was chosen to make these drawings for the Warren Commission since he was only 22 and had been drawing for only one year. There were many other veteran illustrators in the area the Warren Commission could have called upon, but Rydberg came to believe that it was his inexperience that caused the commission to pick him.

When Humes and Dr. Thornton Boswell appeared before him, they had nothing with them: no photos, no x-rays, no official measurements, speaking only from memory, nearly four months after the autopsy, Rydberg said. [DiEugenio, Reclaiming Parkland, pgs. 119-22] The Rydberg drawings have become infamous for not corresponding to the pictures, measurements, or the Zapruder film.

For Humes to endorse these on national television – and for CBS to allow this without any fact-checking – shows what a case of false journalism the special had become.

Limiting Access

CBS also knew that Humes said he had been limited in what he was allowed to do in the Kennedy autopsy, a potentially big scoop if CBS had followed it. Instead, the public had to wait another two years for the story to surface at Garrison’s trial of Clay Shaw when autopsy doctor Pierre Finck took the stand in Shaw’s defense. Finck said the same thing: that Dr. Humes was limited in his autopsy practice on Kennedy. [ibid, p. 115]

The difference was that this disclosure would have had much more exposure, impact and vibrancy if CBS had broken it in 1967 rather than having the fact come up during Garrison’s prosecution, in part, because the press corps’ hostility toward Garrison distorted the trial coverage.

So, in the summer of 1967, CBS again had come to the defense of the official story with a four-hour, four-night extravaganza that again endorsed the findings of the Warren Commission.

At the time of broadcast, it was the most expensive documentary CBS ever produced. It concluded: Acting alone, Lee Harvey Oswald killed President Kennedy. Acting alone, Jack Ruby killed Oswald. And Oswald and Ruby did not know each other. All the controversy was Much Ado about Nothing.

Unwinding the Back Story

In 1967, the clandestine relationship between CBS News President Salant and Warren Commissioner McCloy was known to very few people. In fact, as assistant producer Roger Feinman later deduced, it was likely known only to the very small circle in the memo distribution chain. That Salant deliberately wished to keep it hidden is indicated by the fact that he allowed McCloy to write these early memos anonymously.

As Feinman concluded, McCloy’s influence over the program was almost certainly a violation of the network’s own guidelines, which prohibit conflicts of interest in the news production, probably another reason Salant kept McCloy’s connection hidden.

In the 1970s, after Feinman was fired over a later dispute regarding another example of CBS News’ highhanded handling of the JFK assassination – and then obtained internal documents as part of a legal hearing on his dismissal – he briefly thought of publicizing the whole affair (which he eventually decided against doing).

But Feinman wrote to Warren Commissioner McCloy in March 1977 about the ex-commissioner’s clandestine role in the four-night special a decade earlier. McCloy declined to be interviewed on the subject, but added that he did not recall any contribution he made to the special.

But Feinman persisted. On April 4, 1977, he wrote McCloy again. This time he revealed that he had written evidence that McCloy had participated extensively in the production of the four-night series. Very quickly, McCloy got in contact with Salant and wrote that he did not recall any such back-channel relationship.

In turn, Salant contacted Midgley and told the producer to check his files to see if there was any evidence that would reveal a CBS secret collaboration with McCloy. Salant then wrote back to McCloy saying that at no time did Ellen McCloy ever act as a conduit between CBS News and her father.

However, in 1992 in an article for The Village Voice, both Ellen McCloy and Salant were confronted with memos that revealed Salant was lying in 1977. McCloy’s daughter admitted to the clandestine courier relationship. Salant finally admitted it also, but he tried to say there was nothing unusual about it.

Reassuring Americans

So, in 1967, CBS News had again reassured the American people that there was no conspiracy in President Kennedy’s murder, just a misguided lone gunman who had done it all by himself. Anyone who thought otherwise was confused, deceptive or delusional.

However, in 1975, eight years after the broadcast, two events revived interest in the JFK case again. First, the Church Committee was formed in Congress to explore the crimes of the CIA and FBI, revealing that before Kennedy was killed, the CIA had farmed out the assassination of Fidel Castro to the Mafia, a fact that was kept from the Warren Commission even though one of its members, Allen Dulles, had been CIA director when the plots were formulated.

Secondly, in the summer of 1975, in prime time, ABC broadcast the Zapruder film, the first time that the American public had seen the shocking image of President Kennedy’s head being knocked back and to the left by what appeared to be a shot from his front and right, a shot Oswald could not have fired.

The confluence of these two events caused a furor in Washington and the creation of the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) to reopen the JFK case.

Having become a chief defender of the original Warren Commission findings, CBS News moved preemptively to influence the new investigation by planning another special about the JFK case.

CBS’s Sixty Minutes decided to do a story on whether or not Jack Ruby and Lee Oswald knew each other. After several months of research, Salant killed the project with the investigative files turned over to senior producer Les Midgley before becoming the basis for the 1975 CBS special, which was entitled The American Assassins.

Originally this was planned as a four-night special. One night each on the JFK, RFK, Martin Luther King and the George Wallace shootings. But at the last moment, in a very late press release, CBS announced that the first two nights would be devoted to the JFK case. Midgley was the producer, but this time Cronkite was absent. Rather took his place behind the desk.

In general terms, it was more of the same. The photographic consultant was Itek Corporation, a company that was very close to the CIA, having helped build the CORONA spy satellite system. Itek’s CEO in the mid-1960s, Franklin Lindsay, was a former CIA officer. With Itek’s help, CBS did everything they could to move their Magic Bullet shot from about frame 190 to about frames 223-226.

Yet, Josiah Thompson, who appeared on the show, had written there was no evidence Gov. Connally was hit before frames 230-236. Further, there are indications that President Kennedy is clearly hit as he disappears behind the Stemmons Freeway sign at about frame 190, e.g., his head seems to collapse both sideways and forward in a buckling motion.

But with Itek in hand, this became the scenario for the CBS version of the “single bullet theory.” It differed from the Warren Commission’s in that it did not rely upon a “delayed reaction” on Connally’s part to the same bullet.

Ballistics Tests

CBS also employed Alfred Olivier, a research veterinarian who worked for Army wound ballistics branch and did tests with the alleged rifle used in the assassination. He was a chief witness for junior counsel Arlen Specter before the Warren Commission. [See Warren Commission, Volume V, pgs. 74ff]

For CBS in 1975, Olivier said that the Magic Bullet, CE 399, was not actually “pristine.” For CBS and Dan Rather, this made the “single bullet theory” not impossible, just hard to believe.

Apparently, no one explained to Rather that the only deformation on the bullet is a slight flattening at the base, which would occur as the bullet is blasted through the barrel of a rifle. There is no deformation at its tip where it would have struck its multiple targets. There is only a tiny amount of mass missing from the bullet.

In other words, as more than one author has written, it has all the indications of being fired into a carton of water or a bale of cotton. If CBS had interviewed the legendary medical examiner Milton Helpern of New York — not far from CBS headquarters — that is pretty much what he would have said. [Henry Hurt, Reasonable Doubt, p. 69.]

Rather realized, without being explicit, that something was wrong with Kennedy’s autopsy. He called the autopsy below par and reversed field on his opinion about pathologist Humes, whose experience Rather had praised in 1967. In the 1975 broadcast, Rather said that neither Humes nor Boswell were qualified to perform Kennedy’s autopsy and that parts of it were botched.

But let us make no mistake about what CBS was up to here. The entire corporate upper structure — Salant, Stanton, Paley — had overrun the working producers and journalists, including Midgley, Manning and Schorr. And those subordinates decided not to utter a peep to the outside world about what had happened.

Not only Cronkite and Rather participated in this appalling exercise, so too did Eric Sevareid, appearing at the end of the last show and saying that there are always those who believe in conspiracies, whether it be about Yalta, China or Pearl Harbor. He then poured it on by saying some people still think Hitler is alive and concluding that it would be impossible to cover up the assassination of a President.

But simply in examining how a major news outlet like CBS handled the evidence shows precisely how something as dreadful and significant as the murder of a President could be covered up.

Much of this history also would have remained unknown, except that Roger Feinman, an assistant producer at CBS News, had become a friend and follower of the estimable Warren Commission critic Sylvia Meagher. So, Feinman knew that the Warren Commission was a deeply flawed report and that CBS had employed some very questionable methods in the 1967 special in order to conceal those flaws.

When the assassination issue returned in the mid-1970s, Feinman began to write some memoranda to those in charge of the renewed CBS investigation warning that they shouldn’t repeat their 1967 performance. His first memo went to CBS president Dick Salant. Many of the other memos were directed to the Office of Standards and Practices.

In preparing these memos, Feinman researched some of the odd methodologies that CBS used in 1967. Since he had been at CBS for three years, he got to know some of the people who had worked on that series. They supplied him with documents and information which revealed that what Cronkite and Rather were telling the audience had been arrived at through a process that was as flawed as the one the Warren Commission had used.

Feinman requested a formal review of the process by which CBS had arrived at its forensic conclusions. He felt the documentary had violated company guidelines in doing so.

Establishment Strikes Back

As Feinman’s memos began to circulate through the executive and management suites – including Salant’s and Vice-President Bill Small’s – it was made clear to him that he should cease and desist from his one-man campaign. When he wouldn’t let up, CBS moved to terminate its dissident employee.

But since Feinman was working under a union contract, he had certain administrative rights to a fair hearing, including the process of discovery through which he could request certain documents to make his case. His research allowed him to pinpoint where these documents would be and who prepared them.

On Sept. 7, 1976, CBS succeeded in terminating Feinman. But the collection of documents he secured through his hearing was extraordinary, allowing outsiders for the first time to see how the 1967 series was conceived and executed. Further, the documents took us into the group psychology of a large media corporation when it collides with controversial matters involving national security.

Only Roger Feinman, who was not at the top of CBS or anywhere near it, had the guts to try to get to the bottom of the whole internal scandal.

And Feinman paid a high personal price for doing so. Feinman’s contribution to American history did not help him get his journalistic career back on track. When he passed away in the fall of 2011, he was freelancing as a computer programmer.

[This article is largely based on the script for the documentary film Roger Feinman was in the process of reediting at the time of his death in 2011. The reader can view that here.]

James DiEugenio is a researcher and writer on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and other mysteries of that era. His most recent book is Reclaiming Parkland.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten