Hotter Days, Higher Costs

Essentials get pricier, Jane Hayward on the roots of China’s market turn, and this month’s recommended reads.

Hello listeners/readers,

Welcome back to THE FIX, the monthly newsletter from MACRODOSE. You’ll have noticed that we’ve moved over to Substack. No major changes incoming – just getting in on the action and making things easier for you to read, share, and stay in the loop. Anyway…

Last week, fresh figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) revealed that UK inflation has hit its highest level in almost 18 months. Prices rose more than expected in the 12 months to June, pushing inflation to 3.6% - the highest since January 2024.

Driving this trend was, you guessed it, the rapidly rising price of essentials. Food, clothing, air and rail fares all saw significant increases, while fuel prices didn’t fall as sharply as they did this time last year. According to consumer data company Worldpanel by Numerator, food prices alone have jumped 5.2% over the past month compared to 2024, with the average household on track to spend £275 more on food and drink.

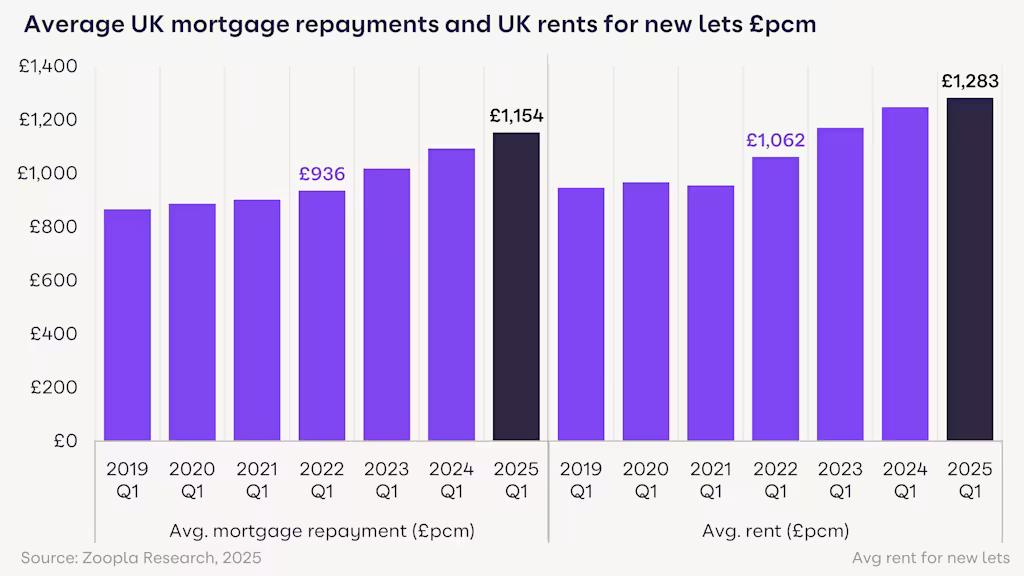

Meanwhile, new analysis from property company Zoopla shows the average monthly rent in the UK this spring reached £1,283. Rents for new tenancies are now 21% higher – or typically £221 more per month – than they were three years ago. And with the supply of rental properties either falling or failing to meet demand, the pressure on tenants continues to mount.

These developments reinforce a pattern we’ve been tracking here on MACRODOSE. The world is entering a new economic era. One marked by the slow grind of inflation – driven increasingly by the climate crisis and global supply shocks - that’s reshaping the post-war assumptions of cheap goods and easy growth in the West.

Luckily, James is away from the show this summer writing a new book about exactly that. So in his absence, the team have lined up a new series of MACRODOSE Histories – bite-sized explorations into the origins of modern economic thought.

Earlier this month, James launched the series with a brilliant primer on Rosa Luxemburg, the Jewish Polish-German revolutionary and Marxist theorist. Today, we continue with a comparative look at John Maynard Keynes, perhaps the most influential economist of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, THE CURVE discussions have continued apace. Last week we heard from Jane Hayward, who offered a sharp, empirically grounded overview of China’s political economy - tracing the complex interplay between domestic politics, international economics, and modern Chinese history. In this month’s host note (see below), Jane leans on recent scholarship to critically revisit China’s so-called “Great Transformation” - the wave of economic reforms launched under Deng Xiaoping in 1978.

Finally, a huge thank you to all *900* of you who joined the Planet B team at the Union Chapel earlier this month for our live event: State of the Nation. If you missed it, keep an eye on the MACRODOSE feed. Next week we’ll be posting recordings of Dalia Gebrial in conversation with Kwajo Tweneboa, and Gary Stevenson with Kojo Koram.

▦ HOST NOTE

(For this month’s host note we hand over to recent guest Jane Hayward, who explores new writing on China’s so called ‘economic miracle’)

Histories of modern China often convey a sense of clear periodization. There’s the dark chaos of the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, then Mao dies, then an amorphous power struggle ensues, from which Deng Xiaoping emerges as paramount leader in 1978; he launches the Reform and Opening movement, at which point the slate is wiped clean for a new beginning.

This is an “end of history” version, in which a backward China was always destined to join the modern world of open markets and burgeoning consumerist lifestyles. All that was needed was the right kind of enlightened leader to put the right policies in place, and that was Deng.

There are two problems with this narrative. The first is its sense of inevitability, which occludes the question of how this most dramatic shift—from the turbulence of Maoist socialism to the breakneck speed of Dengist marketization—actually happened. The second is that the story of China’s Reform and Opening is primarily recounted as a change in economic policy at the top.

Two books came out last year that challenge this predetermined and one-dimensional version of history—The Great Transformation: China’s Road from Revolution to Reform by Odd Arne Westad and Chen Jian, and China’s Age of Abundance: Origins, Ascendance, and Aftermath by Wang Feng.

Both grapple with the complex question of how China’s extraordinary historic shift took place, tracing its roots back to well before 1978. And both seek to foreground a bottom-up perspective, highlighting the importance of ordinary people’s experience of living through this momentous period.

Westad and Chen begin with the great social philosopher Karl Polanyi, who emphasized that markets do not magically appear on their own. All economic systems, including markets and capital, are produced out of particular social, cultural, and political contingencies. In the case of China, Westad and Chen locate these in what they call “the long 1970s,” a period that lasted from 1968 to 1985.

This choice is significant. The dynamism of the 1970s is too often obscured in accounts of the market reforms, submerged into the decade-long “official” Cultural Revolution, the whole of which is too often associated with the traumatic upheavals of the first two years.

Their chronological resetting allows the authors to incorporate key factors often missed in the standard historical accounts, including the growing hostility of relations with the Soviet Union, which fueled Mao’s “obsession” with the possibility of war, and which, by sheer circumstance, happened to coincide with Richard Nixon’s desire to extricate the United States from the Vietnam War. This coincidence enabled the Sino-US rapprochement of 1972. A shift in Party discourse and policymaking followed, with a downplaying of class struggle and an increased emphasis instead on modernization and development (which, of course, we seldom associated with the Cultural Revolution).

Meanwhile, as Party officials were still distracted by Cultural Revolutionary matters, unofficial and unauthorized grassroots market activities sprung up under the radar. These activities, Westad and Chen argue, were driven by the fear and desperation of those who had lived through both the famine of the Great Leap Forward (1958–62) and the political instability of the 1960s. People sought to buttress material security in any way they could, devoid of any certainty that conditions would not once again take a nosedive.

After Mao’s death, the reticence shown by Hua Guofeng, his immediate successor, in dealing once and for all with the “historical issues” of the Cultural Revolution set the conditions for his rapid replacement by Deng. Instead of recognizing the need to issue an official verdict promptly, Hua demurred, leading those who had been persecuted during the era, and who had now returned to leading political circles, to swing behind Deng in frustration. Had Hua been more savvy in putting this issue to rest, the surge behind his rival may not have gathered such momentum. Once it did, and Deng took over—in practice, if not in title—the grassroots conditions were already in place for the market reforms to catch fire.

In China’s Age of Abundance, Wang likens our attempts to make sense of China’s reforms to several people trying to work out what an elephant looks like by each person only touching one part of it.

While many have described the economic policies from the top, he sets out to provide a comprehensive account from the ground level, showing in detail how people’s daily lives have changed.

His chosen angle is consumption, and the pages are packed with data and graphs describing remarkable transformations from before the era of reforms up until, in many cases, the 2020s.

An early anecdote about a mischievous four-year-old child stealing an egg in 1972, at the time an “enviable luxury” and meant for his ailing father, sets the scene. The following chapters detail changes in the availability of food, household appliances, clothing, education, healthcare, and housing.

Even with all the numbers, the book is engaging and accessible. There are some fascinating insights that bring home the significance of these changes for people’s lives. In parts of rural China in the 1960s, there were some households in which family members had to take turns going out because they did not have enough clothes to cover everyone.

Compare this to the year 2000, when China exported 1.56 billion pairs of shoes—the equivalent of every person in China making a pair for export. Another striking detail is the rapid change in children’s height, “virtually unprecedented in the history of human physical development.” At primary school age, a boy in urban China was 5.2 cm taller in 2002 than in 1992, and a girl 5.7 cm taller. In rural areas, the difference between a seven-year-old boy and girl across the same 10-year gap was 7.8 and 7.9 cm respectively.

Like Westad and Chen, Wang also makes clear that the success of the market reforms was not predetermined. In fact, as he emphasizes, the dramatic transformations were most unexpected (the first chapter is titled “Surprise”) and rested on certain specific conditions.

While the resultant economic growth is often put down to China’s abundance of cheap labor, Wang emphasizes that it was more than that—this was good labor, which was made cheap. First, the Mao era, while marked by scarcity, did, from the mid-1960s onward, result in a healthy (if often hungry) population, and also raised literacy levels to an impressive extent. When the reforms began, Chinese workers were fit and ready, and they could read instructions.

Second, a large portion of Chinese workers, the rural migrants, had their labor made extra cheap because of preexisting institutions. The household registration system, under which the rural and urban populations had been governed separately since the 1950s, restricted the rights of rural people while they were in the cities. As a result, their wages were kept low in comparison with their urban counterparts. This highly exploitative system was favored by investors, both domestic and international, which helped to keep the flow of money coming in.

While the access to low-paid jobs in cities did help to raise living standards in the countryside, the legacy of urban-rural inequality remains today, after the age of abundance has ended. This income gap is now proving to be a stumbling block as China’s leaders try to raise household spending while economic growth slows.

At a time when China’s rise seems to many to have been inevitable, both books serve well to remind us of the contingency of history and the opaqueness of the future when viewed from the present.

When Xi Jinping took the helm in 2012, few foresaw China’s repressive political turn or the abolishment of leadership term limits. In a contemporary op-ed in The Wall Street Journal published shortly after his inauguration, a highly respected China analyst observed Xi’s tolerant reaction to a protest against political censorship at the Guangdong-based newspaper Southern Weekly. This analyst presented Xi as an economically liberal reformer and noted how he branded himself after Deng Xiaoping. Xi might find that the greatest risk to his rule, the analyst warned, was his own “softness” toward political dissent. How different things have turned out to be. One day, history books will be written on how we got from there to here.

This text is an abridged excerpt from a recent LARB piece by Jane Hayward, read the original here. Also, listen to Jane on last week’s episode of THE CURVE here.

▦ FURTHER READING

(A list of sources, recent articles and essential reading.)

Read: We all got our tiny violins out for this cracker of a headline earlier this month – “Non-dom exodus hits London market for butlers” [Financial Times]

Read: A study led by the Barcelona Supercomputing Centre directly links dozens of climate extremes to sharp grocery price rises, highlighting the increasing vulnerability of food systems to environmental shocks. [Carbon Brief]

Read: James asks why it is Reform who is leading the pack proposing radical changes to neoliberal monetary orthodoxies. [New Statesman]

Listen: Daniel Denvir is joined by Isabella Weber, Malcolm Harris, and Paul Williams discuss the controversial book Abundance by Derek Thompson and Ezra Kleinand [The Dig]

Read: Low water levels after heatwaves and drought are forcing vessels to sail partially loaded on some of Europe’s biggest rivers, pushing up transport costs. [The Guardian]

Read: Australia has begun offering a first-of-its-kind “climate visa” to citizens of Tuvalu, a Polynesian island nation vulnerable to rising sea levels, albeit by a lottery scheme [New York Times]

Read: Andrew Elrod and Ben Fong discuss the ways organising is evolving, with workers experimenting outside union structures to build power. [Phenomenal World]

Read: Ilias Alami write on the “changing face” of geopolitics – “It is not simply over territorial control that powers now vie, but over the newly vital strategic networks that connect the world economy.” [The Break–Down]

Read: In the face of recent fatal flooding events in Texas, “the Trump Administration is actively undermining the nation’s ability to predict—and to deal with—climate-related disasters.” [New Yorker]

Read: Hannah Martin makes the case for fair adaption, without losing sight of decarbonisation [The Guardian]

Read: As demand grows for the precious minerals needed for the clean energy transition, recent analysis “reveals an alarming rise in human rights and environmental abuses associated with the exploration, extraction and processing of these minerals.” [Business & Human Rights Resource Centre]

Read: Here are several sources from the first episode in our summer history series, on the ecological economics of Rosa Luxemburg [Link] [Link] [Link]

Read: MACRODOSE listener Rhône explores how climate-driven feedback loops and ecological pressures are starting to backfire on human systems, marking the beginning of an era of “planetary blowback.” [Substack]

Caught something we missed? Let us know what you’ve been reading/watching/listening to this month down in the comments?

▦ BOOK CLUB

(A deeper dive into topics covered on the show.)

Our Country in Crisis: Britain's Housing Emergency and How We Rebuild by Kwajo Tweneboa

Kwajo Tweneboa (recent guest at Planet B’s State of the Nation talk) offers a powerful look at Britain’s ongoing housing emergency in his book Our Country in Crisis. Drawing from his frontline experience as an activist, Tweneboa exposes the human cost of decades of neglect – from Grenfell to rising homelessness and toxic living conditions. It’s a clear-eyed call for urgent, radical change that challenges readers to rethink how we build communities and support vulnerable people. Essential reading for anyone concerned about the housing crisis in Britain.

Find the MACRODOSE ESSENTIALS reading list over on our bookshop.org page here, along with book suggestions from past guests on the show. You’ll also be able to buy the books from the list AND at the same time support the show - for every book you buy via our reading lists, bookshop.org gives us 10%. Treat yourself and stock up on some new additions to your bookshelf!

▦ MERCH

Check out what we’ve got in stock over on the MACRODOSE merch store here. As a special thank you, we’re offering subscribers 15% off our merch. Use the code MACRO15 at the checkout.

Every purchase helps support the podcast and ensures we can keep delivering insights and analysis in 2025. Together we are building a new era of independent, people-powered economics media!

Here's something interesting to read: a set of ideas for transforming one of the keystone institutions of the neoliberal era - the multinational corporation.

https://criticaltakes.org/the-corporation/so-what-should-we-do-about-corporate-power/

I wrote the briefing but the ideas aren't mine: they've been collected from across civil society in various countries. The briefing argues that these various ideas, which respond to different manifestations of corporate power, need to be brought together into a common agenda.