MLK & Fred Hampton Versus J Edgar Hoover

James DiEugenio tracks the FBI boss and his renegade violence against any sign of a Black Messiah through two current films.

Martin Luther King Jr., front row & second from left, at March on Washington, Aug, 28, 1963. (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons)

By James DiEugenio

Special to Consortium News

In the late afternoon of April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Martin Luther King Jr. was preparing to go to dinner with some friends. As he stepped out onto the balcony of his room at the Lorraine Motel, he was killed by an assassin’s bullet that struck him in the cheek.

In the late afternoon of April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Martin Luther King Jr. was preparing to go to dinner with some friends. As he stepped out onto the balcony of his room at the Lorraine Motel, he was killed by an assassin’s bullet that struck him in the cheek.

In the pre-dawn hours of Dec. 4, 1969, in Chicago, a drugged Fred Hampton was wounded in his sleep during a police raid on his rented apartment. He was then killed by two more bullets, after which — according to Hampton’s fiancee, Debra Johnson who was on the scene — the officer said, “He’s good and dead now.”

The arc drawn between those two murders outlines more than the death of those two men. In effect it was the end of what was known as the black activist movement. The project that King was working on at the time of his death, the Poor People’s March, ended as a tragic failure. The Black Panther movement was deprived of the member who many thought had the greatest potential for leadership. King was 39. Hampton was 21.

Two new films, one a documentary and one a feature film, now depict the careers and demises of Hampton and King. But Judas and the Black Messiah by Shaka King and MLK/FBI by Sam Pollard go further than that. They attempt to show the reasons behind their deaths.

In both films, with much justification, the finger of guilt points towards FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. No one knows why Hoover had a phobia towards any kind of strong leadership that would galvanize the grievances of black Americans. But there is no doubt he did. It extended back for decades, even before he became FBI director.

As part of the General Intelligence Division, which surveilled radical groups, Hoover’s first African-American target was black nationalist Marcus Garvey. One of the tactics he used, as he would later against King and Hampton, was infiltrating Garvey’s organization with agents of Garvey’s own race.

As time went on, Hoover’s pathology on the subject did not subside. If anything, it increased. But it now co-mingled with another perceived menace, namely communism. For instance, according to Kenneth O’Reilly, in his book Racial Matters, in Hoover’s eyes, the terrible Detroit race riot of 1943 was caused by communist agitation.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in 1959. (Wikimedia Commons)

Eventually, the director’s obsession grew into a fear of what he labeled the rise of a Black Messiah; a leader who would galvanize the race issue to the point that he could threaten the entire American political establishment. Paul Robeson was not in any way a Black Messiah. Yet Hoover tappedRobeson’s phone, opened his mail, got his concert engagements canceled, and attempted to find sexual blackmail on the singer/actor.

All of these illicit and unethical activities were done under a veil of secrecy; simultaneously, according to Hoover biographer Curt Gentry, using FBI media assets to smear Hoover’s targets.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference

In the book J Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets, Gentry says the FBI director opened files on King in 1957, shortly after the success of the Montgomery bus boycott. The bureau’s goal was to find an association with either communists or communist sympathizers. In Racial Matters, O’Reilly writes that Hoover’s grand ambition was to tie King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), to Moscow, thereby discrediting King, the SCLC and its allies.

Pollard’s documentary film MLK/FBI focuses on King’s association with his friend and colleague Stanley Levison. Levison was an attorney and businessman. He raised funds for the SCLC, offered legal advice, drafted speeches, and edited King’s first book Stride Toward Freedom.

Levison was never really a communist, although he did support some of their causes, like sparing the lives of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were controversially convicted of espionage for the Soviet Union and executed. But another supporter, Jack O’Dell had been a member, even though he had left the party years earlier. O’Dell worked out of the SCLC New York office.

Levison was never really a communist, although he did support some of their causes, like sparing the lives of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were controversially convicted of espionage for the Soviet Union and executed. But another supporter, Jack O’Dell had been a member, even though he had left the party years earlier. O’Dell worked out of the SCLC New York office.

Because he was so influential with King, Hoover thought Levison should be their main target. When Levison suggested O’Dell become King’s personal assistant in Atlanta, Hoover took this as proof of the Moscow plot. In 1962, Hoover decided to go full bore against King and the SCLC, using his stooges in the mainstream press. O’Dell was placed on suspension.

In early 1963, Hoover truly feared the upcoming March on Washington that August. He also resented the White House for getting behind the demonstration. The Kennedy brothers were doing much more than Eisenhower had done on civil rights. They were supporting the Brown v. Board of Education decision and working to strike down Jim Crow in the South.

So, Hoover devised another way to use these communist suspicions about Levison and O’Dell. He would weaponize the reports to drive a wedge between King and the Kennedys.

Hoover inundated both the White House and the Justice Department with a steady stream of paper insinuating King was under the influence of communists, and that both O’Dell and Levison were active in CPUSA activities, according to Gentry’s biography of Hoover.

President Kennedy, in a walk with King in the Rose Garden, warned King about Hoover’s surveillance and his tactics, and how this threatened both of them. King ultimately terminated O’Dell and said he would freeze out Levison.

Wiretapping King

After the success of the March on Washington, Hoover discovered that King still had ties to Levison. Hoover now asked Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to approve a wiretap on King. He sought this permission even though, as authors such as Harris Wofford and Curt Gentry have shown, Hoover had already been tapping King since the late 1950s. Hoover had authorized over 20 secret “black bag jobs” — breaking and enterings — against the SCLC prior to 1963. He was now enlisting the attorney general to give him an official cover.

RFK approved a tap against the Atlanta SCLC office for a period of 30 days, after which he would review the results, and if nothing was there, discontinue it. This was on Oct. 21, 1963. We all know what happened one month later.

The eternal flame at the John F. Kennedy grave site in Arlington National Cemetery. (Tim Evason/Wikimedia Commons)

As the film shows, with his friend Lyndon Johnson in the White House, Hoover’s campaign against King moved into another gear. Whereas JFK’s Attorney General Bobby Kennedy had demanded that a negative dossier on King assembled by Hoover be withdrawn from government offices, Hoover now attacked King in public, calling him a notorious liar.

King tried to fight back, saying that Hoover and the FBI were lax in their investigations of crimes by white racists. At the signing of President Kennedy’s Civil Rights Act in 1964, Johnson invited Hoover to sit near the front row during the ceremony. This is around the same time that the FBI sent the infamous “sex tape” of King in a hotel room to the SCLC Atlanta office. There was a threatening note enclosed saying King would soon be exposed as a philanderer. Therefore, if he knew what was best for him, he should kill himself.

King briefly spoke out against Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War in 1965. He was then scolded by other civil rights leaders since a split on Vietnam could endanger their standing with the White House.

But in 1967 King saw a photo essay in Ramparts magazine. Entitled “The Children of Vietnam,” it depicted the indiscriminate bombing and napalming of civilians. King now began to attack the administration over the war. His famous speech at Riverside Church in New York in 1967 now made him a target of not just Hoover and Johnson, but of an editorial in The New York Times and one in The Washington Post.

President Lyndon B. Johnson shaking hands with Martin Luther King Jr. at the signing of the Voting Rights Act on Aug. 6, 1965. (Yoichi Okamoto, LBJ Library, Wikimedia Commons)

Hoover had enlisted two informants on King. One was photographer Ernest Withers. The other, according to David Garrow in The FBI and Martin Luther King Jr., was office employee Jim Harrison. As King now began to expand his focus to Vietnam and poverty, Hoover began to ramp up COINTELPRO (counter intelligence program) operations against both civil rights groups and leftist press and organizations like the Students for a Democratic Society, or SDS.

These entailed the employment of not just spies, but agent provocateurs inside these organizations. And as King now began to arrange his Poor People’s Campaign, the FBI “discovered” that King was present at the rape of a parishioner, and he looked on and laughed. As one of the commentators in the film notes, if this was just an audio tape, how could the agents know King was “looking on.”

As the film depicts, after King’s assassination, rioting, looting and burning took place in over a hundred American cities. To the film’s credit, Andrew Young states that the accused killer, James Earl Ray, had nothing to do with the crime.

But the film also says that Hoover did a crackerjack job investigating King’s assassination. This leaves out two important points.

No. 1 In late March, the FBI prepared a memorandum saying that King has stayed at the Holiday Inn previously in Memphis. On King’s return, the SCLC booked a room at the African American-owned Lorraine Hotel. But before he arrived, someone — to this day no one knows who it was — changed the location of the room. This made it possible for King to be shot from his balcony facing the street.

No. 2 Another conclusion in MLK/FBI is that the FBI is not a renegade organization, that it is really part of the establishment. Perhaps this is so, but not under Hoover. The case of Fred Hampton pretty much demonstrates it was a renegade organization against African Americans.

The Black Panthers & Fred Hampton

The Black Panther Party began in 1966 in Oakland under Bobby Seale and Huey Newton. In its gun-toting militancy it really owed more to Malcolm X than King. The Panthers carried guns in order to check instances of police brutality — they called it “cop watching.”

The Black Panther Party began in 1966 in Oakland under Bobby Seale and Huey Newton. In its gun-toting militancy it really owed more to Malcolm X than King. The Panthers carried guns in order to check instances of police brutality — they called it “cop watching.”

In direct response to this, the next year, Governor Ronald Reagan and the California legislature struck down the state’s open carry law. In October of 1967, Newton was wounded and a police officer killed in a gun battle.

These kinds of incidents — the opposite of King’s non-violent approach — spurred recruitment of new members and the opening of new chapters nationwide. As did a famous picture of Newton sitting in a wicker chair with a rifle and a spear. At its peak in 1970, there were 68 local chapters and thousands of members. But the Panthers also offered free breakfast programs, the opening of health clinics and political education classes.

All of the above did not sit well with Hoover. In 1969 he labeled the Panthers “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” He called for an extensive COINTELPRO program to neutralize them.

William Sullivan, the man directing these activities, said the Panthers were the black equivalent of the Klan, according to O’Reilly’s book Racial Matters. Anyone in the bureau who resisted that characterization, and the programs Sullivan arranged, was given an ultimatum and a deadline. Charles Bates of the San Francisco office initially resisted and Sullivan gave him two weeks to change his mind. He decided to go along for the sake of his career. The COINTELPRO began in the San Francisco/Oakland area.

Hoover’s campaign against the Panthers was probably the most extensive, violent, and relentless counter-intelligence program the FBI ever devised. It consisted of surveillance, infiltrations, agent provocateurs, police perjury, ersatz threatening letters and other techniques. In addition to that, the bureau reached out to other law enforcement organizations in order to multiply the effect and to disguise the bureau’s own role in what would eventually become the destruction of the Panthers. There is probably no better example of this than the assassination of Fred Hampton.

Hampton began his career as an effective community organizer for the NAACP. Attracted by the more radical approach of the Panthers, Hampton decided to join the Chicago branch.

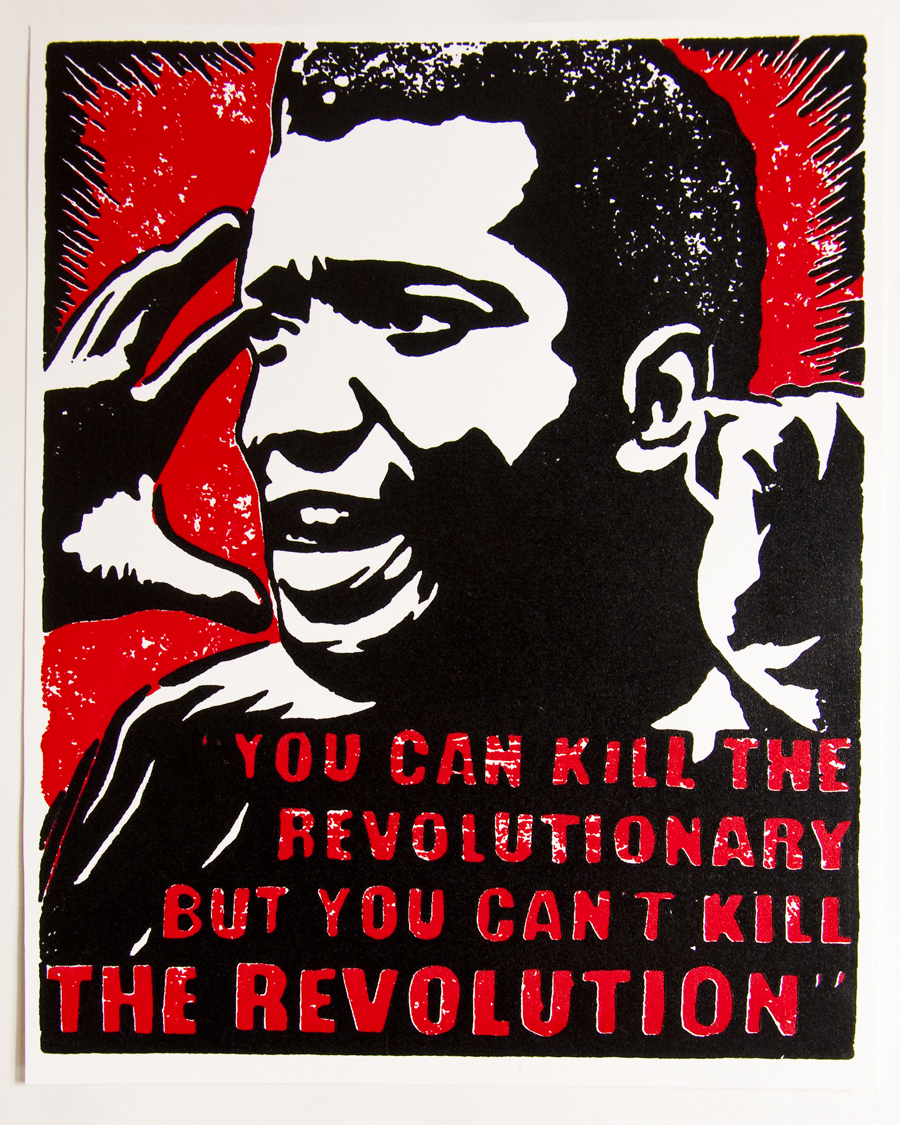

Fred Hampton poster. (Jacob Anikulapo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

According to then Attorney General Ramsey Clark, Hoover was aware of Hampton before anyone else in government was. Hampton was a dynamic speaker, with a forceful yet malleable personality. He was an imaginative and innovative organizer. One of his most notable achievements — depicted in the new film Judas and the Black Messiah — was his attempt to incorporate street gangs into the Panthers so they would not feud with each other. He also tried to make this coalition multi-racial, including Hispanics, Native Americans and the white working class. He named it the Rainbow Coalition. He was so effective that he became the Panthers’ state chairman and at the time of his death, he was about to be appointed to chief of staff for the national organization.

The film depicts the police planting an informant in Hampton’s office. William O’Neal had raided bars impersonating an FBI officer. Once the unsuspecting clientele turned over their wallets and keys, he would steal a car. Eventually caught, the FBI threatened to send him to prison for about six years. O’Neal decided to become a combination informant/provocateur on Hampton for his Bureau control agent, Roy Mitchell.

O’Neal helped set up a raid at the Panther’s Chicago headquarters that resulted in eight arrests. A later raid at Panther headquarters, as depicted in the film, turned into a shootout. When the occupants surrendered, the police went in and torched one floor of the building. During a Nov. 13, 1969, gun battle on the South Side of Chicago, two policemen and one Panther were killed.

The police and FBI were so desperate to put Hampton away, that they charged him for stealing $71 worth of ice cream bars. He was convicted for this and received a two-to-five-year sentence. His attorneys had him temporarily released. Even though Hampton had been ordered back to prison, Mitchell asked O’Neal for a floor plan of Hampton’s apartment that indicated where Hampton slept.

At about 4:30 AM on Dec. 4, 1969, 14 policemen detailed to the Cook County State Attorney’s office executed a raid for weapons. The police had 27 guns, five shotguns, and one machine gun. The lead cop was James Davis, an African American who had a reputation for brutalizing black suspects.

Hampton had been drugged by O’Neal with secobarbital. He did not wake up during the fusillade. Davis broke down the door and shot Panther Mark Clark through the heart. As Clark fell dead, he discharged his weapon into the floor. That was the only shot fired by a Panther. The police fired over 90. Four other occupants of the apartment were wounded.

As noted above, the pattern of the fatal bullets into Hampton were at close range and into his forehead and temple. The Cook County attorney in charge of the assault, Edward Hanrahan, had agreed to conceal the FBI’s role in the illegal raid. The pretext was the Panthers had illegal guns; it turned out the guns were all legally purchased and registered.

Shaka King has directed the film in a workmanlike manner. He lays the story out clearly and does not draw attention to himself. The script, by King and Will Berson, is as accurate as one will find in a historical film. It uses the latest information garnered by attorneys Flint Taylor, Jeff Haas and historian Aaron Leonard to implicate Hoover directly in the activities of Mitchell and O’Neal. Daniel Kaluuya plays Hampton. His portrayal is fine until you watch film of the real Hampton. Imagine a young Samuel Jackson in the role.

Both these films are worth seeing. It’s rare to see Hollywood treat a serious subject seriously. America is still recovering from the reign of J. Edgar Hoover. The legendary lawman once said, “Justice is incidental to law and order.” The results of that motto are found in these films.

James DiEugenio is a researcher and writer on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and other mysteries of that era. His most recent book is The JFK Assassination : The Evidence Today.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

https://consortiumnews.com/2021/03/05/mlk-fred-hampton-versus-j-edgar-hoover/

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten