How Venezuela Re-elected Maduro, Defying the U.S.

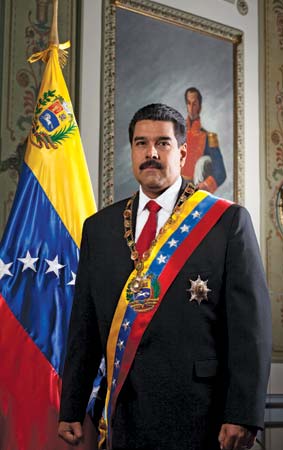

Nicolás Maduro overcame intense opposition from Washington and rich Venezuelans to be re-elected, but he’s not out of the woods yet, as Roger D. Harris explains.

By Roger D. Harrisin Caracas

The Venezuelan people reelected Nicolás Maduro for a second presidential term on May 20, bucking a U.S.-backed political tide of reaction that had swept away previously left-leaning Latin American governments – often by extra-parliamentary means – in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Honduras, and even Ecuador.

The Venezuelan people reelected Nicolás Maduro for a second presidential term on May 20, bucking a U.S.-backed political tide of reaction that had swept away previously left-leaning Latin American governments – often by extra-parliamentary means – in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Honduras, and even Ecuador.

The United States and the right-wing opposition in Venezuela had demanded an election boycott and Maduro’s resignation. Instead, a majority of Venezuelans defiantly voted for Maduro, affirming the legacy of Hugo Chávez.

Chávez was first elected in 1998 and died in office on March 5, 2013. He had spearheaded a movement that turned Venezuela from an epigone of Washington into an independent force opposing U.S. hegemony. The Bolivarian Revolution reclaimed Venezuela’s history and forged a new national identity that no longer looked to Miami for affirmation. Even some of the most anti-chavismo now take pride in being Venezuelan. Such has been the depth of the sea change in national consciousness.

Venezuelan society became more inclusive for the poor, especially women, people of color, and youth. Of the 300-odd mayoralties in Venezuela, over 100 mayors are under 30 years old. As historian Greg Grandin observed, this inclusiveness has awakened “a deep fear of the primal hatred, racism, and fury of the opposition, which for now is directed at the agents of Maduro’s state but really springs from Chávez’s expansion of the public sphere to include Venezuela’s poor.”

On a geopolitical level, the Bolivarian Revolution placed a renewed focus on opposing U.S. dominance. While some on the left have become confused about opposing imperialism, Washington has made regime change in Venezuela a priority.

Maduro inherited all this and more: a dysfunctional currency system, deeply engrained corruption, an entrenched criminal element, a petro-economy dependent on the international market, and the eternal enmity of Washington.

Maduro’s First Election – Yo Soy Chávez

The Venezuelan people first elected Maduro president on April 14, 2013, in a nation still reeling from the death of Chávez just five weeks before after snap presidential elections were called according to the constitution.

Chávez was bigger than life when he was alive. In death Chávez emerged even larger. Even for the 6’ 3” former bus driver and union leader, these were very big shoes for Maduro to fill.

In graffiti on the walls of working class neighborhoods and on red tee-shirts worn by the chavista faithful, the slogan of the 2013 election was Yo Soy Chávez (I am Chávez). Maduro had been Chávez ’s foreign minister starting in 2006 and vice president and then Chávez ’s designated successor in 2012, though he remained largely unknown.

Maduro’s Baptism by Fire

Chávez’s death was a traumatic moment for the Venezuelan people, and an opportunity not to be missed by the U.S. and largely well-off Venezuelan opposition to roll back the revolution. Maduro had no grace period, nor did he waver.

The main opposition candidate in 2013, Henrique Capriles, appeared on national TV within moments of the announcement of Maduro’s election victory and declared the election a fraud. He then called upon the Venezuelan people to “express their rage.”

What ensued was the opposition incited violence (guarimbas) of 2013, followed by the 2014 wave of escalated violence, and then the even more destructive violence of 2017. Mainly confined to middle class opposition neighborhoods, the violence destroyed billions of dollars of public property including buses and public transportation facilities, health clinics and hospitals, schools and universities.

Even more costly were the loss of more than one hundred people who perished in the violence: some opposition, more chavistas, and many bystanders. In the most recent round of violence, the most extreme opposition elements have burned suspected chavistas alive because of their skin color.

Declare close election losses as fraudulent; boycott elections they don’t have a chance of winning and then call those results as fraudulent; and finally initiate street violence to provoke an over-reaction from the government.

U.S.-aligned big business in Venezuela has contributed to the opposition offensive by creating selective shortages in consumer goods as part of what has become known as the economic war. While liquor stores are fully stocked, according to a young woman from the state of Táchira bordering Colombia, items such as feminine hygiene products and diapers are scarce, targeting the grassroots chavista leadership, which is mainly female.

The Obama administration declared Venezuela an “extraordinary national security threat” in 2015 and has since, continuing with the Trump administration, piled on ever increasing economic sanctions. U.S.-led diplomatic efforts have been designed to isolate Venezuela and further pressure Maduro simply to give up and resign.

After Maduro’s accession to the Venezuelan presidency, international petroleum prices plummeted, dealing a near decisive blow to the country’s economy. Revenues from petroleum sales fund the vast social programs of the Bolivarian Revolution, as well as paper over the economic inefficiencies that Maduro had inherited and the outright mistakes and corruption under his own watch.

Both the opposition and Maduro have targeted corruption within the ranks of Chávismo. But for Maduro there has been no winning for trying. When he attacks corruption in his own ranks, he is accused of being authoritarian. His former attorney general, Luisa Ortega Díaz, who was removed for corruption, and fled the country on a speedboat, has been elevated to a political martyr by the opposition.

Both the opposition and Maduro have targeted corruption within the ranks of Chávismo. But for Maduro there has been no winning for trying. When he attacks corruption in his own ranks, he is accused of being authoritarian. His former attorney general, Luisa Ortega Díaz, who was removed for corruption, and fled the country on a speedboat, has been elevated to a political martyr by the opposition.

Why Maduro was Reelected

Under normal conditions, Maduro’s prospects for reelection in 2018 would have looked dismal. Venezuela was experiencing hyper-inflation, GDP growth was negative, and critical shortages were piling up. The U.S. and its hemispheric allies in the anti-Venezuelan Lima Group were trying to invoke the charter of the Organization of American States (OAS) militarily to intervene in Venezuela based on a “humanitarian crisis.”

While hardship today in Venezuela is undeniable, it does not rise to a level of humanitarian crisis. That’s the fake news. Well-stocked stores and lively commerce are plainly in view in much of Caracas.

The real news is that even though Venezuela has the funds to buy vital medicines and food stuffs, such efforts are being blocked by U.S., Canadian, and European Union sanctions. In other words, the enemies of Venezuela are hypocritically condemning the very conditions they are exacerbating.

The rightwing opposition is united in their class antipathy to the main beneficiaries of the Bolivarian Revolution: the poor and working people of Venezuela. But the opposition, despite assistance from the U.S., has been divided over whether to try to overthrow Maduro by illegal means or electorally.

The opposition has won only two of some two-dozen major national elections since 1998. On that basis it complains of a “dictatorship,” while former U.S. President Jimmy Carter calls Venezuela’as the best electoral system in the world.

When the opposition won the National Assembly elections in December 2015, they had no program to address the dire economic problems facing the country. Instead, they passed an amnesty law for illegal activities some in the oppositon had engaged in, such as narco-trafficking, perpetrating coups, and terrorism.

A constitutional stalemate between the opposition-dominated National Assembly and the chavista-dominated Supreme Court then paralyzed government. Maduro exercised a constitutional provision to call for a national election to create a Constituent Assembly with power over both warring branches of government. The chavista electoral victory in July 2017 so demoralized the already divided opposition, that they ceased mounting violent actions. Venezuela has enjoyed relative domestic peace since.

Meanwhile a resilient Maduro government has maintained and extended core social programs such as building two million housing units for the poor. Measures taken include creating the Petro crypto-currency, revaluing the regular currency, distributing food through the CLAP program, setting up subsidized trucks selling arepas (Venezuelan equivalent of the taco), diplomatically forging closer relations with China and Russia, and most of all relying on the strength of the chavista base.

The Opposition to Maduro’s Second Election

First the U.S. and the Venezuelan opposition accused Maduro of not calling a presidential election. So Maduro called an election, and then they accused him to setting it too early. In on-again-off-again negotiations with elements of the opposition, the election was moved to a later date and then again to a still later date, settling on May 20, 2018.

The U.S. and the main opposition coalition, Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD), instead called on Maduro to call off elections and resign. In effect, any election they could not win had to be fraudulent. The opposition called for yet more punishing U.S. sanctions on their own people and echoed the U.S. in threatening a coup, all in the name of “restoring democracy.”

Henri Falcón broke ranks with the MUD and ran a weak campaign against Maduro, despite intense pressure from the U.S. and the non-electoral opposition to boycott the election. Falcón had been the campaign manager for Capriles, the 2013 opposition candidate.

Falcón’s main program was to replace the Venezuelan currency with the U.S. dollar, which would address inflation but would also prevent the government from using fiscal means to manage the national economy. He also advocated taking massive loans from the IMF and other institutions of international capital. The chavistas characterized his program as selling out Venezuela to foreigners.

Falcón had signed a pledge to recognize whomever won the election, which he promptly reneged on within minutes of losing, predictably claiming “irregularities.”

Maduro’s Second Election – Vamos Nico

Only 46 percent of eligible voters cast ballots on May 20, a turnout comparable to many U.S. elections and the election of French President Emmanuel Macron in 2017, but low by Venezuelan standards. Nevertheless, Maduro received a larger percentage of the eligible vote in Venezuela than did Barack Obama in 2012 or Donald Trump in 2016 in U.S. presidential elections.

Besides the opposition boycott, people sympathetic to Maduro were not motivated to vote in an election they saw as not tightly contested.

Not only did Maduro sweep the contest with 68 percent of the vote, but he emerged as his own man from Chávez’s shadow. Maduro had forged deep personal ties with his supporters, evident from a red sea of supporters triumphantly chanting “vamos Nico” (“go Nico,” with Nico, short for Nicolás) when Maduro went to the National Electoral Council for the official notification of his campaign.

Maduro won reelection on a playing field tilted against him. But will his movement succeed in righting the economy as he promised on a playing field tilted even more precipitously against his government? Already the Trump administration has imposed new sanctions designed to prevent recovery, further punishing the Venezuelan people for voting the way they wanted.

A version of this article first appeared on Venezuela Analysis.

Roger D. Harris is immediate past president of the 32-year-old anti-imperialist human rights organization Task Force on the Americas. He was an election observer in Venezuela for both of Maduro’s elections, most recently on a delegation with Venezuela Analysis and the Intrepid News Fund.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten