The Literati’s Scourge of Putin and Trump

Masha Gessen and Her Questionable Views

“I have spent a good third of my professional life working to convince the readers—and often editors—of both Russian and American publications that Vladimir Putin is a threat to the world as we know it.” Thus spake Russian-born journalist and author Masha Gessen, a current heroine of the more intellectual part of the PC hive.

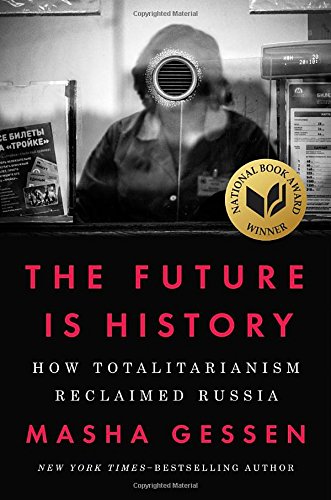

Gessen is a staff writer for the highbrow New Yorker and also a regular contributor to the New York Review of Books and the New York Times, writing on such topics as Russia, autocracy, L.G.B.T. rights, Vladimir Putin, and Donald Trump. She is the author of nine books, her most recent being The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia, which won the National Book Award in 2017.

To understand Gessen’s mindset, it is important to look at her background. She was born in what was then the Soviet Union in 1967 to secular Jewish parents, and says she suffered from anti-Semitism. The 1970s were a time when Russian Jews began to strongly oppose the Soviet state, with many of the leading dissidents being Jewish.[1]

Gessen’s family was among the many Soviet Jews who emigrated to the United States, hers doing so in 1981. With the fall of Communism, however, she returned to Russia in 1991, where, working as a journalist, she remained until December 2013, when she would return to the United States out of fear that the Russian government’s new anti-homosexual propaganda law could be used to take away her adopted children, since she was regarded as “Russia’s leading LGBT rights activist.”

Her new book, The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia, released at the beginning of October 2017, is now causing a stir. (This essay is not a review of this book, but it should be mentioned that it is a fairly good read and shows that Gessen is not completely one-sided.) More than a few commentators focus on the title’s reference to “totalitarianism.” But has Russia really returned to its totalitarian past? It should be noted that Gessen’s arguments in this book (which is also the case elsewhere) seem to have been either too erudite, convoluted, or contradictory for her reviewers to grasp. For example, the review in the Washington Post’s print version asks: “Is Putin’s brand of totalitarianism as repressive as Stalin’s?”[2] (This question is a loaded question since it contains an unjustified assumption—that Putin’s Russia is totalitarian. This is tantamount to the proverbial “Have you stopped beating your wife?”) The review’s author, Susan B. Glasser, former Moscow bureau chief for the Washington Post and co-author of a book on Putin, acknowledges in an overall favorable review that “Gessen’s provocative conclusion that Putin’s Russia is just as much a totalitarian society as Stalin’s Soviet Union or Hitler’s Germany may not convince all readers.”

In the New York Times, Francis Fukuyama likewise holds that Gessen sees Russia as being totalitarian: “As the subtitle of her book suggests, she believes that totalitarianism has reclaimed the country.” Fukuyama points out, however, that “One cannot really label Russia as totalitarian in the absence of a strongly mobilizing ideology.” In a favorable review in the Guardian, Daniel Beer, similarly refers to “Gessen’s extravagant claim: Putin’s regime is a ‘totalitarian’ successor of the murderous dictatorships of Stalin and Hitler.”

In various magazine articles, however, Gessen states directly, or implies, that Putin’s Russia is not a full-fledged totalitarian state, although it is moving in that direction . In an interview in Time Magazine, published in early October 2017, Gessen explicitly states that “[t]he regime that exists in Russia is not a totalitarian regime. Putin has created the regime of a mafia state. But because he created this regime on the ruins of a totalitarian society, totalitarian habits have kicked in. It’s a bizarre situation, where the regime sends out signals that aren’t about establishing totalitarian control. The regime just wants to plunder and stay in power. But society, which has been conditioned by so many years of totalitarianism, responds by creating totalitarian mechanisms, [like] when people start raiding bookstores in their own neighborhoods to make sure there is de facto censorship.”

Gessen also provides seemingly contradictory interpretations about why Russia was moving in a totalitarian direction. She maintains that the whole course of history had been changed with Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2015 and that this was the delayed response to the NATO bombing of Serbia during the Kosovo war in 1999. Russians regarded “Yugoslavia [as] being a rightful part of Moscow’s sphere of influence. Not being consulted—or even, apparently, warned—sent the very clear message that the U.S. had decided it now presided over a unipolar world. There was no longer even the pretense of recognizing Russia’s fading-superpower status.” Russians felt humiliated. Thus, Putin’s efforts to restore Russia’s military power were welcomed by the Russian public. “[B]y annexing Crimea,” Gessen asserts, “he [Putin] had avenged Russia for what had happened with Kosovo.” She opined that “[i]t is also impossible to know whether Putin would have happened to Russia if it had not been for the [NATO] bombing of Yugoslavia. I believe he would not have.” And it is Putin who has moved Russia in a totalitarian direction.

While Gessen is willing to accept the idea that NATO bombing of Serbia angered and humiliated Russians and caused an aggressive reaction, she denies that the U.S. expansion of NATO to include former Soviet satellites violates any Western promises to the contrary. It is this expansion of NATO, however, about which Putin now fulminates.[3]

But contrary to what Gessent claims , recently released documents from the National Security Archives at George Washington University clearly “show that multiple national leaders were considering and rejecting Central and Eastern European membership in NATO as of early 1990 and through 1991, that discussions of NATO in the context of German unification negotiations in 1990 were not at all narrowly limited to the status of East German territory, and that subsequent Soviet and Russian complaints about being misled about NATO expansion were founded in written contemporaneous memcons [memoranda of face-to-face conversation] and telcons [memoranda of telephone conversation] at the highest levels.”

Denying that Putin has been really affected by NATO expansion, Gessen holds that his hostility to the U.S. and the West reflects “a clash of civilizations, nothing lessthan a confrontation with the West over the very values at the core of ‘the Russian world.’ The current view is that international law and all Western alliances are parts of a conspiracy to limit Russia’s ability to protect and spread traditional values. So-called strategic interests and the fate of ethnic Russians are merely pretexts for battles in the new worldwide conflict.”

“The West hopes its actions can change Putin’s [actions],” Gessen maintains.“Negotiating with Putin, trying to second-guess him, validating his bad-faith negotiations, searching for a solution that can mollify him—all of these approaches are willfully based on a false assumption. The very premise of realpolitik in this situation is a lie.”

It is not clear what Gessen actually means here. Does she really believe there is a “clash of civilizations,” or is she referring to what she regards as the current Putin line, similar to the old Soviet party line that could quickly be changed to advance other political interests? But Gessen clearly denies that alleged Russian geostrategic interests and the condition of ethnic Russians living outside of the Russian Federation really motivate Putin’s policy.

Yuri Levada (1930-2006), founder of the Levada Center, which conducts surveys of Russian public opinion, coined the term “Homo Sovieticus” to describe the average Soviet citizen–a fearful, isolated, authority-loving personality created by Communism. Adopting this analysis, Gessen writes in The Future is History: “The belief in a paternalistic state, and an utter dependence on it, were bred in Homo Sovieticus by the very nature of the Soviet state, which, Levada wrote, was not so much a complex of institutions, like the modern state, but rather a single superinstitution. He [Levada] described it as a ‘universal institution of a premodern paternalistic type, which reaches into every corner of human existence.’ The Soviet state was the ultimate parent: it fed, clothed, housed, and educated its citizen; it gave him a job and gave his life meaning; it rewarded him for doing good and punished him for doing wrong, no matter how small the transgression. ‘By its very design, the Soviet ‘socialist’ state is totalitarian because it must not leave the individual any independent space,’ wrote Levada.”[4]

In the early 1990s, after the collapse of Communist rule, this type of individual seemed to be disappearing, and Levada, Gessen points out, thought it would become extinct as the Soviet generation died off, but by the end of that decade public opinion polls indicated that this was not the case. Upset with their country’s loss of status and longing for stability, Homo Sovieticus was, by the latter part of the tumultuous 1990s, “not only surviving but reproducing – and this meant that he was reclaiming his dominant position in the population.”[5]

Gessen implies here that the attitudes of the Russian people shape the type of government under which they live. It would seem, therefore, that Putin, or someone like him, was bound to rule Homo Sovieticus. This conflicts with her negative references to Putin in which he seems to be history-shaping.

What policy toward Russia does Gessen propose? In September 2014, she advocated that the U.S. “use the entire arsenal of financial and political sanctions at once” to wreck the Russian economy, which is about what the United States has done.

“After that,” she asserted, the United States should “do what can be done to physically protect those who are being attacked and those who are at risk: Ukraine, the Baltics, and – the most important criterion of all – anyone who asks for protection from this scourge. That probably means arming Ukraine and taking up positions in the Baltics. Yes, this puts the West on the verge of actual military engagement, but it is not only strategically dangerous but also morally corrupting to stand by and watch while Putin pounds unprotected neighbors.

“It is likely that none of this [will] stop him [Putin],” Gessen opines. “But at least it may keep us from falling into an abyss of lies and helplessness.”

Note that Gessen accepts the fact that her proposal would put the West on the “verge of actual military engagement”—that is, war—but she considers it to be morally wrong to do nothing to counter Putin. Moreover, she doubts that this effort would achieve success. Going to war, especially one that could lead to a horrendous result—i.e., nuclear war—while doubting success is a clear violation of just war principles.

Gessen, however, wants to do more than just protect countries from Russian aggression; she wants to destabilize Russia itself. She writes: “Bombing Moscow does not seem to be an option. [Note that she does not categorically rule this out.] But helping the Russian opposition in the same committed, involved, and even meddling manner as the U.S. once helped the Serbian opposition should be.” Gessen grants “that Putin is a lot stronger and harder to remove.” But she holds that this provides all “the more reason for the U.S. to put its best minds to work on helping Russians accomplish just this. It may be our only chance of righting the course of history.”

Gessen does not even stop with regime change. She wants Russia to break apart and thinks that Putin’s fall from power could precipitate that. “Russia continues to be an empire in a world that has pretty effectively dispensed with empires,” she avers. “So why is the Russian Federation of more than 80 constituent parts, most of which have distinct national identities, some of which have distinct languages and cultures, and all of which now, as a result of being plundered by the Putin regime, have nationalist movements – why should they stay together?” Gessen’s animosity is not simply toward Putin, but toward Russia, and it would seem, the bulk of the Russian people—as exemplified in the Homo Sovieticus theory—who, she believes, have essentially created the type of government that exists. Gessen’s vision for the future of Russia bears some resemblance to the harsh Morgenthau Plan for post-World War II Germany that proposed its pastoralization based on the assumption that it was not simply the Nazis who were dangerous but the German people. And it should be further noted that Stratfor, an American global intelligence firm that has been referred to as the “Shadow CIA,” predicts Russia’s breakup.

Gessen sees some similarities between Putin and Donald Trump. However, she rejects the narrative prevalent among many mainstream American liberals that Russian meddling in the 2016 election enabled Trump to triumph. Gessen writes this off as a conspiracy theory—conspiracy theories being repudiated ipso facto by the mainstream, and when the mainstream adopts this mode of thinking, as it has on the Russia issue, it is not referred to as a “conspiracy theory.” Gessen maintains that “conspiracies are perfect for simple thinking. . . . Because Russiagate explains how we got Trump and how we’re going to get rid of Trump. Russia elected him, and once it all comes to light, he’s magically going to disappear.”

Gessen writes: “These ideas—that Trump is like Putin and that he is Putin’s agent—are deeply flawed.” In her view, the “Putin fixation” is “a way to evade the fact that Trump is a thoroughly American creation that poses an existential threat to American democracy.” And she concludes her argument by appealing to the Marxist-Freudian Frankfurt School of sociology: “In the middle of the last century, a number of thinkers whose imaginations had been trained in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany tried to tell Americans that it can happen here. In such different books as Erich Fromm’s Escape from Freedom, Theodor Adorno and his group’s The Authoritarian Personality, and Herbert Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man, the great European exiles warned that modern capitalist society creates the preconditions for the rise of fascism. America doesn’t need Putin for that.” [Note that this would seem to undercut the Homo Sovieticus theory, which emphasizes the specific environment of the Soviet Union.]

Laying ou t her own theory for Trump’s victory, Gessen sermonizes: “Trump got elected on the promise of a return to an imaginary past—a time we don’t remember because it never actually was, but one when America was a kind of great [sic] that Trump has promised to restore. Trump shares this brand of nostalgia with Vladimir Putin, who has spent the last five years talking about Russian ‘traditional values,’ with Hungarian president Viktor Orbán, who has warned LGBT people against becoming ‘provocative,’ and with any number of European populists who promise a return to a mythical ‘traditional’ past.”

In Gessen’s view , the greatest fear of these autocratic simplifiers is LGBT rights. “With few exceptions,” Gessen opines, “countries that have grown less democratic in recent years have drawn a battle line on the issue of LGBT rights. Moscow has banned Pride parades and the ‘propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations,’ while Chechnya—technically a region of Russia—has undertaken a campaign to purge itself of queers.” She also includes Orban’s Hungary, Erdogan’s Turkey, Modi’s India, and el-Sissi’s Egypt in this “less democratic” category.

“The appeal of autocracy lies in its promise of radical simplicity, an absence of choice,” Gessen asserts. “In Trump’s imaginary past, every person had his place and a securely circumscribed future, everyone and everything was exactly as it seemed, and government was run by one man issuing orders that could not and need not be questioned. The very existence of queer people—and especially transgender people—is an affront to this vision. Trans people complicate things, throw the future into question by shaping their own, add layers of interpretation to appearances, and challenge the logic of any one man decreeing the fate of people and country.”

There is ample historical evidence to refute Gessen’s contention that the existence of “queer people” is antithetical to autocracy, since that label could be applied to such autocrats as Roman emperors Caligula, Nero, and Hadrian; Alexander the Great and Frederick the Great. Furthermore, Nazism used to be connected with homosexuality when homosexuality was considered to be a deviant behavior. For example, in his popularly acclaimed historical work, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, published in 1960, establishment author William Shirer described Ernst Röhm, head of the notorious Stormtroopers (SA), as “a tough, ruthless, driving man—albeit like so many of the early Nazis, a homosexual.”[6]

In an article written before Trump was elected president, Gessen claimed that he “will have to begin destroying the institutions of American democracy—not because they get in the way of anything specific he wants to do, like build the wall . . . but because they are an obstacle to the way he wants to do them. A fascist leader needs mobilization. The slow and deliberative passage of even the most heinous legislation is unlikely to supply that. Wars do, and there will be wars. These wars will occur both abroad and at home. They will make us wish that Trump really were Putin’s agent: at least then there would be no threat of nuclear war.”

“There is no way to tell who will be targeted by the wars at home,” Gessen avers, but she regarded it most likely to be “the LGBT community because its acceptance is the most clear and drastic social change in America of the last decade, so an antigay campaign would capture the desire to return to a time in which Trump’s constituency felt comfortable.”

While usually focusing on Trump as though he is radically different from other American presidents, Gessen acknowledges that the conditions for autocracy are the result of the American reaction to the September 11 terrorist attack. “The state of emergency that went into effect three days after September 11th has never been lifted,” she points out. And she maintains that, concomitantly, there has been a “16-year run of . . . [an] increasing concentration of power in the executive branch.” Gessen states that this “chain of events did a lot to create the possibility of Trump, to create the very possibility of a politician who could run for autocrat in this country and get elected.”

Whereas Gessen rails against Putin and Trump for purportedly suppressing freedom of speech in their countries, she explicitly rejects this concept as illustrated by her following pontification: “Otherwise sane Americans routinely argue that the regulation of speech is incompatible with liberal democracy. This is a patently untrue statement. To take just one example, virtually all member countries of the European Union have so-called memory laws, which outlaw certain statements about history. A great many Americans are convinced that the right to free speech in this country is absolute, as though various American authorities did not police pornography, the portrayal of sex in movies, and the language used by broadcast media, to name just a few of the most obvious speech-regulation practices that Americans encounter every day.”

Note that Gessen is claiming that the belief that “regulation” of speech is incompatible with liberal democracy is “insane.” One might recall that the Soviet Union in its more “tolerant” latter days labeled dissidents as insane and needing treatment with psychiatric drugs. The fact that members of the European Union have laws prohibiting political and historical views does not mean that such a prohibition is not contrary to a free society, and it is certainly contrary to the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of speech as interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court. Sometimes so-called liberal democracies, including the U.S., have acted in an illiberal manner. In 1952, when Communist subversion was a major concern, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, a liberal icon, stated that “Restriction of free thought and free speech is the most dangerous of all subversions.”

Apparently, Gessen believes that pornography should not have less protection than speech pertaining to politics, science, and history, which has never been the case in the United States or, until perhaps recently, in other Western countries. Nonetheless , pornography is not currently banned in the United States.

Gessen also wants to make sure that views she opposes are kept out of academia and is upset when this does not happen. Regarding an effort to have a dissident view expressed at the University of California-Berkley, she writes: “Milo Yiannopoulos, that gay firebrand of homophobia and misogyny, will be appearing at so-called free-speech events at Berkeley this week, with his allies Steve Bannon, Ann Coulter, and James Damore, the former Google employee who gained fame with his pseudoscientific memo on women in tech.” It is not clear why people such as Damore, with his alleged pseudoscience, cannot be easily refuted. Wouldn’t it be better to refute these ideas than prohibit them? People, especially the highly intelligent students who attend Berkeley, might come to think—though may be fearful of expressing–that the reason for suppressing ideas is that they cannot be refuted.

Gessen was also enraged that the annual conference at the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College allowed among its more than 20 speakers–which included Gessen–a German rightist parliament member, Marc Jongen, to express his opposition to immigration in Germany. Gessen complained: “If the organizers’ intent was to facilitate a debate with a living specimen of the new far right, it failed. What Jongen said had been heard before, and could have been discussed in his absence. More to the point, whatever the organizers’ intention, an invitation to talk at a famous center at a prestigious college does lend legitimacy to the speaker and his views.” In other words, opposition to immigration is outside the bounds of allowable opinion, although most countries have laws restricting immigration.

Gessen claimed that Hannah Arendt, a major writer on totalitarianism, would have held the same view, contending that “she stressed the simplicity and the ‘preposterous’ nature of ideas that underlie evil: these were ideas to be called out, not debated. She was also sensitive to the appearance of legitimacy that an invitation can lend. In December 1948, she signed a letter to the Times about the visit to the United States of the Israeli politician Menachem Begin, whose organization the letter likened to the Nazi Party.” However, there doesn’t seem to be any equivalency between Jongen’s verbal opposition to immigration and Begin’s leadership of the terrorist group Irgun, which engaged in mass murder to dispossess the native Palestinians.

While Gessen is a skilled and prolific writer, far more intelligent than most PC feminine icons, her radical lesbianism—which seems to be the cynosure of her Weltanschauung and serves as a significant reason for her intense hostility to Putin—mars her objectivity. But it undoubtedly increases her appeal to the liberal establishment. Also contributing to her appeal is her willingness to sometimes differ from the current PC party line—e.g., on Russiagate—while not straying beyond the bounds of allowable thought. Thus, she is often proclaimed to be provocative, a quality undoubtedly enhanced by her inconsistencies: one cannot predict exactly what she will say.

Gessen seems to believe that views she supports should be given free rein while views she detests should be prohibited. If Gessen wants to look at totalitarianism, autocracy, or any other fearful development she conjures up, she would do well to study her own mind. And she might be able to recognize that she is as much a product of Soviet Communism as Homo Sovieticus was, but instead of being an obedient follower, she is more like a would-be Soviet commissar.

[1] Yuri Slezkine, The Jewish Century, Princeton University Press, 2004.

[2] Susan B. Glasser, “Is Putin’s brand of totalitarianism as repressive as Stalin’s?,” Washington Post, p. B-1 and B-5, October 8, 2017.

[3] Masha Gessen, The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia, Penguin Publishing Group, Kindle Edition, pp. 275-77.

[4] Gessen, The Future is History, Kindle, p. 59.

[5] Gessen, The Future Is History, Kindle, pp. 201-202.

[6] William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, 1960, Pdf version, p.35. WikiSpooks Main-page.png — An encyclopedia of deep politics., https://wikispooks.com/wiki/File:The_Rise_And_Fall_Of_The_Third_Reich.pdf

RSS

RSS

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten