- Untitled work auctioned for most ever for an American artist

- Painting acquired by Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa

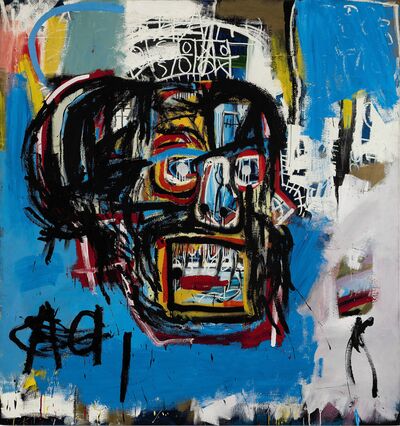

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s painting of a skull sold for $110.5 million at Sotheby’s in New York, setting an auction record for American artists and providing a windfall for the daughter of two collectors who purchased it for $19,000 in 1984.

Jean Michel-Basquiat, Untitled 1982

Source: Sotheby’s

The buyer was billionaire Yusaku Maezawa, founder of a Japanese fashion website, and a new force in contemporary art. The work led four days of bellwether auctions in New York where the world’s wealthiest investors and families dropped more than $1.5 billion on Impressionist, modern, postwar and contemporary art. The results surpassed the target of $1.3 billion and the series conclude on Friday.

Basquiat’s canvas was last purchased at auction three decades ago by the late New York collectors Jerry and Emily Spiegel. It then disappeared from the public view until the couple died in 2009 and their art trove passed on to their two feuding daughters, according to people familiar with the matter.

The elder daughter, Pamela, consigned 107 works to Christie’s, which has sold about 50 lots for $125 million so far this week. The younger daughter, Lise, raised almost as much by selling just one painting -- the Basquiat -- at Sotheby’s. Arthur Sanders, Pamela’s husband, declined to comment on the sale. A representative for the other sister wasn’t immediately able to comment.

The Basquiat propelled Sotheby’s auction results to $319 million in sales, a 32 percent increase from a year ago. Fifty lots were offered and all but two sold.

The bidding for the painting started on May 18 at $57 million, sparking gasps in the packed salesroom, and lasted for more than 10 minutes as three parties chased after the work. The result ended up smashing Andy Warhol’s $105.4 million auction record and making Brooklyn-born Basquiat the most expensive American artist at auction. Basquiat died in 1988.

“I remember astounding the art world back in 1980s when I set an auction record for Basquiat at $99,000,” said Jeffrey Deitch, an art dealer who was the artist’s friend and champion. “All of us, Jean-Michel’s friends, we totally believed in his genius. I always thought he would be one day in the league of Picasso, Bacon and Van Gogh. The work has that iconic quality. His appeal is real.”

Sotheby’s had valued the work at more than $60 million and guaranteed the seller an undisclosed minimum price regardless of the bidding at the auction. Maezawa purchased a separate painting by the artist last year for $57.3 million.

Other Billionaires Bought and Sold Art...

It is a painting that bleeds history. Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (1982) portrays a black skull scarred with red rivulets, pitted with angry eyes, gnashing its teeth, against a blue graffiti wall on which someone has been doing their sums. Perhaps the street mathematician was calculating how many Africans died on slave ships in the 18th century, or how many people lived in slavery in America, or how many young black men have been killed by police guns in the last few years.

For there is a savage moral truth in the $110.5m paid for Basquiat’s skull at Sotheby’s in New York on Thursday that has made this searing expressionist painting the most expensive American artwork of all time.

Some serious critics – notably the late Robert Hughes, who dismissed Basquiat as a “featherweight” in an excoriation published just months after the 27-year-old painter’s death from heroin abuse in 1987 – might be rolling in their graves to see him anointed by market forces as the only American artist who belongs in the same financial company as Pablo Picasso.

Is Basquiat wilder than Jackson Pollock, more profound than Mark Rothko, more raw than Willem de Kooning? These are conventionally judged the greatest American painters, with Cy Twombly, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol close behind. The buyer is art collector Yusaku Maezawa, whose enthusiasm for Basquiat has singlehandedly driven his prices into outer space; he also set the previous record last year. Who is he to question the verdict of critics, museum collections and, up to now, auction houses about who the Great American Artists are?

He is, I suspect, a romantic. For this is actually a replay of the oldest story in modern culture. Ever since the English poet Thomas Chatterton died aged 17 in 1770 and was mourned as a romantic hero, the idea of the artist maudit, the dark and doomed genius, has created cults and made posthumous fortunes. Vincent van Gogh’s fame is inseparable from our image of his tormented life and premature death. Basquiat’s career was brief and spectacular, and cast in the romantic mould.

Today, in a world when art has become a form of mass entertainment, artistic celebrity and wealth are normal, and art dealers among the most sophisticated economic operators on the planet, it is easy to see why Maezawa is drawn to a man who even in his lifetime was already hailed by some as America’s Van Gogh.

Yet there’s another way to understand his passion for Basquiat, and a better reason to celebrate it. There’s a terrible clarity in Basquiat’s art. Like the work of another heroin user, William Burroughs, his art, with its feeling of being cut and hacked into the canvas rather than daubed, its electric sense of pain in every nerve, shows everyone what’s really in their lunch. He serves up American history with all the worms crawling out of it. This painting of a skull is not just about his own morbidity – it’s about being killed by America.

It did kill him, just as it has killed so many. Basquiat’s skull tells the same truth old blues songs do. It’s the skull of someone lynched. The skull of a slave. The skull of a death-row prisoner.

Sorry Bob – it looks like Basquiat really is a heavyweight after all. His art crawls with the ghosts of America’s racist and fatally cursed House of Usher.

Since you’re here …

… we’ve got a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever, but far fewer are paying for it. Advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

I read it fairly often and enjoy the variety of news and entertainment content. It never occurred to me that you wanted contributions, but I’d like you to stick around. Sometimes you actually have to pay for stuff you like. Go figure.

Mike L

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps to support it, our future would be much more secure.

1 opmerking:

Zowel de verkopers als de er tamelijk jong uitziende koper hebben hun fortuin niet zelf gemaakt, het zijn de kinderen van de 1% en soms de kinderen van de 10% die steevast beleggen in 'kunst' met belastingtechnische voordelen! Hoe de waarde tot stand komt, heeft en dat is het weerzinwekkender, te maken met de rol die de financials; banken en vermogensbeheerders spelen, sinds zeker begin jaren tachtig en kleinschaliger reeds vanaf begin jaren zeventig. Galeriehouders hebben daarnaast niet zelden bijgedragen aan de vroegtijdige dood van getalenteerde kunstenaars waardoor ze hun eigen markt niet konden verpesten door te veel te produceren (Eveneens een kenmerk van de talentvolle kunstenaar de bijna niet te stuitten obesessieve drang tot creëren.)(Herman Brood schepte er een welhaast sardonisch genoegen in juist dat te doen: zijn 'marktwaarde' verzieken) De Duitse kunsthistoricus en onderzoeksjournalist Willy Bongard deed veel onderzoek naar de geldstromen. Toen ik hem had gelezen eind jaren '70 was ik dermate geschokt dat ik de kunstakademie verder voor gezien hield. Een baan in 'de reclame' zag ik ook niet zitten.

"Kunstspekulationen sind der neueste Dreh im Kunstkarussell. Ausführliche Berechnungen über die Verzinsung bei Wertanlagen in Millionenhöhe (bei einem Bild von Henri Toulouse-Lautrec ergaben sich beispielsweise jährlich 7,4 Prozent bei einer Laufzeit von 57 Jahren) werden von kunstinteressierten Finanzexperten unentwegt angestellt. Der Lockruf, mit Kunst ließe sich schnell ein Vermögen verdienen, verhallte nicht ungehört. Die New Yorker „Citibank“ richtete prompt eine Beratungsstelle für Kunstspekulanten ein und streckt sogar Kapital vor.

Andere Großbanken und Konzerne sehen im Kunstkauf einen vergleichsweise kostengünstigen – Weg, ihr Image zu pflegen. Die „Chase Manhattan Bank“ der Rockefellers – diese Familie ist schon seit langer Zeit eine der rührigsten Mäzenaten-Dynastien in den Vereinigten Staaten, häufte über die Jahrzehnte fast 11 000 Kunstwerke an, die nun über alle Geschäftsstellen verstreut vom guten Geschmack der Bankiers künden.

Diesem Beispiel folgten schnell auch deutsche Großbanken. Die Bayerische Hypotheken- und Wechselbank erwirbt zum Beispiel Gemälde aus dem 18. Jahrhundert, die in der Alten Pinakothek als Leihgaben zur Schau gestellt werden. Die Deutsche Bank gab zwei Millionen Mark aus, um ihre beiden Frankfurter Verwaltungstürme mit Kunstwerken vollzustopfen. „Der Kurator einer großen Firma ist mir heute als Sammler lieber als der Kurator eines Museums“, gesteht der Kölner Galeriebesitzer Rudolf Zwirner.

Im Jahrzehnt der Museumsneubauten haben deutsche Kunstverwalter ihre anfänglichen Berührungsängste abgeschüttelt. In den neuen, prächtigen Häusern fehlt nämlich häufig das Geld für die Einrichtung einer entsprechenden Sammlung. „Wenn ich Geld von der Industrie kriegen kann“, sagt der Bonner Museumsdirektor Christoph Rüger, „nehme ich es, egal, was die Manager sich daran versprechen.“ " U.z.w. - Willi Bongard - Kunst ~ Zeit.de 27. März 1987

Een reactie posten