Appreciating the majestic mountain: Hamid Dabashi reflects on Edward Said

ON EDWARD SAID

Remembrance of Things Past

by Hamid Dabashi

250 pp. Haymarket Books $13.96

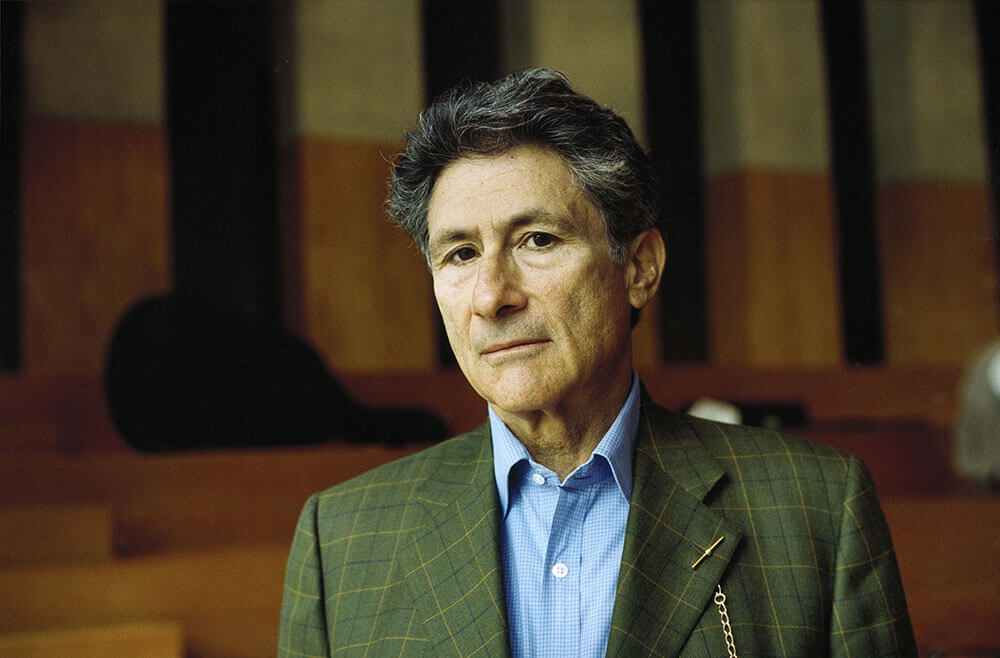

Towering is the adjective Hamid Dabashi uses the most in describing Edward Said and his singular contribution to literary theory, post-colonial studies, and the understanding of Orientalism. In this captivating collection of essays, Dabashi writes about Said, inspired by Said, or in dialogue with Said, even long after he was no longer with us. “Certain towering intellectuals,” Dabashi writes, “become integral to the very alphabet of our moral and political imagination. … They live in those who read and think them through—and thus they become indexical, proverbial, to our thinking.”

Most of this book consists of Hamid Dabashi’s published essays and interviews that seem unrelated to Edward Said. In introducing these writings, however, Dabashi explains how he felt Said was “looking over his shoulder watching every single word” he wrote, never in a domineering way, but in a comradely, dialogical and empowering spirit.

Dabashi reflects upon a fascinating fact that Edward Said “never turned you into a Saidian but enabled your own thinking on the premise he had mapped out.” In other words, Said never employed his outstanding and revolutionary scholarship to hegemonize or suppress others’ thought, as he was “an enabler, not a guru.”

Said “did not replicate himself. His friends became more of themselves by his virtue.” More than anything, this trait reflects Said’s unflinching commitment to progressive critical thinking and to its role in intellectually provoking, kindling, and empowering others’ agencies in the pursuit of justice and the fight against oppression in all its forms.

Dabashi illustrates in several of his essays his own disagreements with Said, including on aspects of his most iconic work, Orientalism, reassuring his readers that though Said might not have concurred with Dabashi’s critique he would have certainly approved of enunciating it in public. “Said was always a catalyst in my thinking—not because we thought alike but precisely because we thought differently. … something about the power of his prose, the urgency of his insights, and the provocative twists of his thinking enabled others to think their own thoughts more pointedly.”

Whereas Said refers in his theory to the center-periphery binary, for instance, Dabashi sees globalization and the current phase of capitalist development as doing away with this binary altogether. “The universe has no center, no periphery,” writes Dabashi. “It is meaningless after Said to speak of ‘exilic intellectuals,’ precisely because he so thoroughly theorized the category for his own age. There is no home from which to be exiled. The capital and the empire that wishes but fails to micromanage it are everywhere. … home and exile are illusions that late capital and the condition of empire have dismantled.”

But for Said, being out of Palestine meant being out of home, in exile. Palestine, in this sense, became the “quintessence of [Said’s] moral outrage,” argues Dabashi. Not only did the power of his narrative emerge out of his “critical intimacy with [its] national liberation movement,” but Palestine, as a metaphor for injustice and resistance, also informed his defense of all the oppressed. “Edward Said single-handedly altered the very language of how we speak about the globality of the condition we know as colonialism. He did so by theoretically universalizing the particularity of Palestine.”

Dabashi describes Said as a “majestic mountain” whose greatness one can never see if sitting under its shadow. “The splendor of mountains … can be seen only from afar, from the safe distance of only a visual, perceptive, appreciative, awe-inspiring grasp of their whereabouts.” In a way, Said saw his Palestine as such a majestic mountain whose indelible agony and prophetic promise could only be grasped from afar, from exile. Dabashi cautions, “We need to keep a careful balance between Palestine as a gushing wound and Palestine as a metaphor.” Said did not just keepthat balance, he was in a very profound way himself such a balance.

True to his commitment to Palestine, well before he met Said, Dabashi throughout this book insists that Palestinian liberation remains a moral quest of our time, inspiring revolutionaries and justice movements around the world. “Zionism,” he writes, “has no pretense even to moral authority or political legitimacy. It is held together by the flimsy scaffolding of corrupt and reactionary US politicians.”

Some readers may dismiss this as wishful thinking that is belied by the current reality of a massively powerful Israel that is more fanatic, brutal and criminal than ever yet enjoys an unprecedented level of both influence and impunity in an international political system dominated by Israel’s partners in crime – the US administration and Europe. But Dabashi is not blinded by the ever-present vestiges of Israeli power, which he sees as transient, but is focused instead on its inherent weakness and vulnerability to the movement for justice and liberation. He accordingly implores Palestinians to play a leading role in “imagining, articulating, and theorizing a post-Zionism polity,” apparently unaware of the fact that some Palestinians, many of whom also sense Said’s gaze over their shoulders, have been doing that for quite some time.

Dabashi speaks for many of us, those who knew Said or were just blessed with the warmth of his intellect in the coldness of despair and relentless oppression, when he says that he is unable to mourn Said, as mourning essentially implies closure, while his intellectual relationship with Said and conversations with him are ongoing even in his eternal bodily absence. By sprinkling some “authentic” Jerusalem soil on the exiled resting place of Edward Said in Lebanon, Hamid Dabashi was at once re-connecting with the “prince of our cause, … source of our sanity in despair, solace in our sorrow, hope in our own humanity” one last time and helping Said, in his eternal exile to “feel” a bit less out of place.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten