Brothers in Armchairs

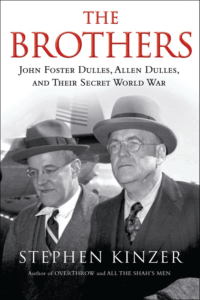

The Eisenhower era is often seen as a placid time, presided over by a president who shunned wars and had a healthy skepticism about big military expenditures. But as Stephen Kinzer’s sparkling new biography, The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War, indicates, Dwight Eisenhower did embrace the idea of regime change abroad, and with a vengeance. His instruments for creating it in Guatemala, Iran, the Congo, and Cuba were John Foster and Allen Dulles, two brothers who grew up in privilege and were groomed to regard it as America’s birthright to exercise its power around the globe, whenever and wherever it saw fit.

They were quite different in personality. John Foster was the dour fire-and-brimstone secretary of state. Harold Macmillan declared, “His speech was slow but it easily kept pace with his thoughts.” Allen, by contrast, was the suave and secretive spymaster (author Rebecca West, asked if she had been one of his mistresses, replied, “Alas, no, but I wish I had been”), but both inherited an evangelical streak that they translated into a secular war against communism. Their influence lingers on in the massive national security state that they helped construct during the early years of the Cold War and that continues to expand and search relentlessly for fresh enemies to justify its own existence.

The Brothers:

John Foster Dulles,

Allen Dulles, and Their

Secret World War

by Stephen Kinzer

Henry Holt, 416 pp.

Both brothers have been the subject of previous biographies, with Allen enjoying perhaps the most perspicuous by Burton Hersh, a longtime student of the intelligence agencies. But Kinzer, a former longtime foreign correspondent for the New York Times, effectively joins them in his panoramic survey of their lives. He traverses a great deal of ground, some of which he previously covered in his study of the 1954 coup in Iran All the Shah’s Men, and he is an acidulous critic of American foreign policy. His main point is that America, or at least a man like Allen Dulles, was not an innocent abroad. Instead, the Dulles brothers were calculating figures who essentially turned American foreign policy into an annex of the business interests of their old law firm Sullivan & Cromwell, deftly annealing moralism about American democracy to their own self-interest. To be sure, Wilsonian liberal internationalism was predicated on the notion that more-interconnected financial interests would tie nations together peacefully. But for much of the eastern establishment to which the Dulleses belonged, the distinction between a corporation’s interests and the American government’s was indiscernible, prompting Kinzer to call John Foster “one of the American elite’s most ruthlessly effective and best-paid courtiers.”

John Foster and Allen Dulles were born into a family of public servants and men of the cloth. Their father was a Presbyterian minister, and his father before him was a Presbyterian missionary. Their maternal grandfather, John Watson Foster, grew up in Indiana on the frontier. He was a newspaper editor who became a stalwart member of the Republican Party and was appointed secretary of state by Benjamin Harrison. Foster encouraged a rebellion in 1893 in Hawaii of white settlers against Queen Liliuokalani and sent troops in to support the insurrection. “This,” writes Kinzer, “made John Watson Foster the first American secretary of state to participate in the overthrow of a foreign government.” After his government service, he set up shop as a lobbyist for big business. As small children, John Foster and Allen got to stay with him in his Dupont Circle mansion, where

[b]oth brothers came to feel at ease in the most rarefied circle. They dined with ambassadors, senators, cabinet secretaries, Supreme Court justices, and other grand figures including William Howard Taft, Theodore Roosevelt, Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, Andrew Carnegie, and Woodrow Wilson.… From these long evenings they absorbed not only the precepts, ideas, and perceptions that shaped America’s ruling class, but also its style, vocabulary, and attitudes.

Pivotal for both brothers was the opportunity to attend the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. They had an important ally in their quest to reach the diplomatic big time: Uncle Robert Lansing, who was Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of state. Neither Allen nor John Foster played big roles in drafting the Treaty of Versailles, but they did make numerous connections. Kinzer believes that the two fell fully under Wilson’s spell: “He was the quintessential missionary diplomat: cool, pontifical, sternly moralistic, and certain that he was acting as an instrument of divine will. Both brothers took his example to heart.”

It is John Foster who attracts Kinzer’s ire more than Allen. For all his moralism, John Foster got it wrong when it came to Hitler’s Germany (unlike Allen, who warned his brother that the Nazis were a dangerous bunch). His deep affection for German culture and learning and his business interests blinded him to the true nature of the Nazi regime. He saw Nazism as a bulwark against communism rather than as a totalitarian society intent on mass murder. John Foster described France and Britain as “static” societies—a precursor of Donald Rumsfeld dismissing “Old Europe”—and claimed that the future would be decisively shaped by new, dynamic powers such as Germany, Italy, and Japan. According to Kinzer, John Foster worked closely with Hitler’s finance minister, Hjalmar Schacht, to help “[t]he National Socialist state find rich sources of financing in the United States for its public agencies, banks, and industries.” John Foster supported the isolationist America First movement. Even though his partners at Sullivan & Cromwell forced him to close the firm’s offices in Berlin in 1935, he remained blasé about the Nazi regime. He visited Germany in 1936, 1937, and 1939: “Apparently nothing he saw disturbed him,” writes Kinzer.

Allen’s great moment of glory, by contrast, came in battling the Nazis as a member of the Office of Strategic Services, which was headed by the World War I hero and lawyer William Donovan. Allen was dispatched to Bern, Switzerland, where he created a web of spies and informants to discover what was happening behind enemy lines and in Nazi Germany itself. Eventually, he began parachuting agents into occupied countries and directing guerrilla attacks on Nazi targets. By 1944, Allen was focused on how best to contain and even roll back Soviet power in postwar Europe. He sought out Nazi commanders in Italy to see if they would agree to an early surrender, and succeeded. Operation Sunrise relied on the cooperation of figures such as General Karl Wolff, commander of SS forces in Italy—who was later found to be complicit in the murder of hundreds of thousands of Jews by a German court—to assent to cutting a deal with the Americans.

With Allen ensconced in Bern, John Foster started his own comeback toward the end of World War II. He had become close friends with the Time magazine publisher Henry Luce, who was busy championing the idea of an American Century. Both were pro-business, internationalist Republicans shaped by Calvinist principles—Luce, born in China, was himself the son of a Presbyterian missionary. Despite Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s initial misgivings, he ended up appointing John Foster to the American delegation to the negotiations in San Francisco in 1945, where fifty countries met, including the Soviet Union, to establish the United Nations. John Foster, who had begun to espouse a militantly anticommunist line, clashed with Andrei Vishinsky, the Soviet deputy foreign minister and former chief prosecutor at Stalin’s purge trials.

But it wasn’t until the 1952 election that the political fortunes of the Dulles brothers were sealed. John Foster pursued a very hard line against communism—rhetorically. But Eisenhower essentially ignored his advice when it came to Korea, where John Foster advised no negotiations and sending armies across the demilitarized zone. Instead, Eisenhower went to Korea and decided to accept a cease-fire. When it came to covert action, however, Eisenhower was more receptive. Allen, who was appointed CIA director, worked hand in glove with his brother to topple various regimes deemed hostile to American interests. But, as Kinzer emphasizes, many of Allen’s projects were busts. He commanded 15,000 employees in fifty countries with an annual budget in the hundreds of millions of dollars, no accounting necessary, but “he had remarkably little to show for it. All three of his main operations in Eastern Europe, aimed at stirring anti-Communist resistance in Poland, Ukraine, and Albania, collapsed in defeat.” In 1960 the U-2 spying incident, in which American Air Force pilot Francis Gary Powers was shot down by Soviet planes, also helped to wreck incipient negotiations with the Soviets over easing the Cold War.

Still, Allen was a busy man at the CIA. Under him the agency had a hand in overthrowing the Mossadegh government in Iran and the Ãrbenz regime in Guatemala, and connived at the murder of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo. What he seems most to have resembled, in the crucible of the Cold War, is former Vice President Dick Cheney. According to Kinzer, he “established secret prisons in Germany, Japan and the Panama Canal Zone.”

But perhaps the brothers’ most malignant legacy was John Foster’s intransigence about Indochina. He told Americans in 1954 that as part of the global crusade against communism it was imperative to counter Ho Chi Minh and his communist forces in North Vietnam. Winston Churchill, for one, was appalled by John Foster’s conduct during negotiations in Geneva over Vietnam’s future in 1954: “Dull, unimaginative, uncomprehending. So clumsy I hope he will disappear.” To John Foster’s horror, negotiations meant that Vietnam would be partitioned and Ho would attain power. He left Geneva in a huff after a week. But successes in Iran and Guatemala, Kinzer reports, had convinced Eisenhower, John Foster, and Allen that this “third monster,” as Kinzer puts it, could be quashed. The road to American military involvement in Vietnam had begun.

The real disasters started after Eisenhower left office. The obsession with ousting Fidel Castro led to the Bay of Pigs, an operation that Eisenhower had told John F. Kennedy was imperative when they met in the Oval Office. Kennedy, young and inexperienced, assented. But Allen Dulles, aging and cavalier, never even bothered to supervise the project, leaving it to his deputy Richard Bissell, who forged ahead in the conviction that even if the motley crew of Cuban exiles came to grief, Kennedy would, at the last moment, rescue them with American firepower. The president refused. And Allen had to resign from the CIA.

In his conclusion, Kinzer suggests that the story of the Dulles brothers is the story of America. “As long as Americans believe their country has vital interests everywhere on earth, they will be led by people who believe the same,” he writes. Kinzer is surely right to raise doubts about the perfervid embrace of American exceptionalism that has become de rigueur for politicians, Democratic or Republican, to asseverate piously. But perhaps he falls into his own form of moralism, his own nostalgia for an America that never really existed, when he seems to posit the existence of an Edenic country that was once free of the corrupting embrace of the rest of the world. For America does, in fact, have interests abroad. The problem with the Dulles brothers is not that they espoused contact with the rest of the world but that they relied on a militarized form of crusading confrontation that continues to bedevil America.

https://washingtonmonthly.com/2013/08/18/brothers-in-armchairs/

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten