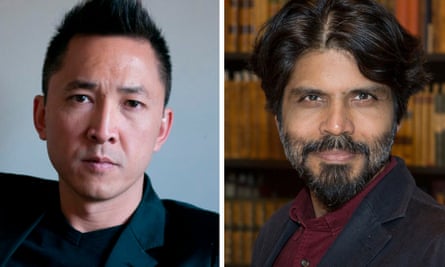

'Free speech has never been freer': Pankaj Mishra and Viet Thanh Nguyen in conversation

Are we living through a moment of lasting change? Two authors discuss Black Lives Matter, the Harper’s letter and where we go from here

Pankaj Mishra: Black Lives Matter has forced a long overdue re-examination, from the perspectives of history’s long-term losers, of everything, not only entrenched political and economic inequities but also the imbalances of intellectual and artistic life. But there is a very long way to go. Your recent article on Spike Lee’s new film about African-American soldiers in Vietnam[Da 5 Bloods] was instructive in this regard. Here is a celebrated African American film-maker, the cinematic biographer of Malcolm X, succumbing to American cliches about the Vietnamese, and non-white foreigners in general.

I am reminded, too, of a prize-winning writer who recently claimed in a tweet that African Americans were “fighting for democracy abroad”. Contrast this casual euphemising of American violence in multiple countries to Muhammad Ali’s principled refusal to join the assault on Vietnam. Such naive Americanism is striking. In the past African American leaders and artists, from WEB Du Bois to Nina Simone, simply assumed solidarity with peoples elsewhere; they could see that the plights of the long-term victims of slave society and the societies despoiled by racial-ethnic supremacism were inseparably linked. What do you think happened to sunder that connection?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I think also of black radicals like Du Bois and Martin Luther King Jr, who are best known in the US for their critiques of racism within American society. Du Bois, of course, would go on after The Souls of Black Folk to be much more international in his life and thinking, and King delivered his speech “Beyond Vietnam” in 1967, near the end of his life. The speech connected anti-black racism with racist American warfare in Vietnam and elsewhere, and posited that these were inseparable. King’s civil rights colleagues didn’t want him to go in that direction. That strand of domestic-centred thinking is still strong.

There’s the positive pull of being American, realised in the election of Barack Obama, symbolically so important for many Americans but especially black Americans. On the negative side, there is the spectre of punishment. Ali was punished, King was murdered, the Black Panthers – who were reading Mao and saw themselves as part of a third world revolution – were violently suppressed. Finally, Obama, Beyoncé, Kanye West, Michael Jordan, and the rest of the black economic, cultural and political elite are international, but not in the radical sense. That’s racial contradiction under a global capitalist economy, when Oprah can be a billionaire and still be racially profiled in a luxury goods store. The liberal-to-moderate-left position is to guarantee that Oprah can be a billionaire without racism, even if many black Americans remain poor (because of both racism and capitalism).

In this racialised economy, Black Lives Matter is an idea, a meme, a phrase that can be commodified and contained. Now it’s relatively safe to take a knee, to wear a BLM shirt. Still, the moment feels different from anything I’ve seen in my lifetime. Quantitatively different, too, with the scale of the protests in the US and outside. I’m guardedly optimistic that there has been a shift in thinking about race in the US. And since race cannot be separated from inequality and exploitation, a shift in thinking about race might be a shift in thinking about these interrelated issues. Are you more pessimistic than I am?

PM: I think I am wary rather than pessimistic. Perhaps because I see the opposition to BLM’s demand for root-and-branch change as deeply entrenched, among liberals as well as white supremacists. Take, for instance, the insidious Harper’s letter, which complains about something usually called “cancel culture” in the midst of the most devastating global crisis since the second world war and massive protests against racism that you rightly call transformative.

You’ll remember that King identified the peddler of “moderation” as the bigger obstacle to social justice than white supremacists. The letter is an example of how elites rush to occupy the moral high ground when their authority as arbiters of intellectual and political life is challenged from both the left and the right. The letter was organised by Thomas Chatterton Williams, a writer much liked by self-proclaimed centrists and moderates as well as rightwingers for his belief that the “root problem in black life” in America is an “intangible smallness of mind” and “moral childishness and sheepish conformity”.

Shouting that “free speech” is in danger has become one way to promote yourself as a custodian of “classical liberalism”, and to accrue some moral and intellectual glamour. The problem for this rich, powerful, but deeply insecure minority is that free speech has never been freer for most people on this planet.

I can personally attest, after nearly 25 years of publishing in mainstream journals, that intellectual discourse has never been more open and diverse. Yes, Niall Ferguson threatened to sue me over a book review, and Jordan Peterson responded to an article by calling me a “prick” whom he would happily beat up; but you have to take such moderate exponents of free speech in your stride if you have a public role. The important thing is that many more people of our background are writing today in mainstream periodicals than they were in the mid-1990s, when I started out. Today we can discuss a range of subjects with a frankness that was simply taboo for decades. Moreover, the public sphere is no longer dominated by the so-called legacy media. We tend to focus on the derangements and corruptions of Twitter. But what about the contributions of historians, economists and sociologists on Twitter and in webzines and small periodicals?

When in the past you read prescriptions for wars and torture in the Atlantic and the New York Times; when the editorial pages of the Financial Times in 2014 said that there is something “thrilling” about the rise of Narendra Modi, you could do nothing except let off an internal scream of impotent despair.

Today, such moral obscenities provoke an immediate response. When Roger Cohen, a columnist at the NYT (and a signatory of the open letter), endorsed Modi’s leadership he faced a tsunami of scorn. When the Economist tells us, with its usual glibness, to deploy “Enlightenment liberalism” against racism, a lot of people can swiftly point out that Voltaire saw black people as only slightly intellectually superior to animals and that Kant thought black people were stupid by nature.

Yascha Mounk, the political scientist who ran Tony Blair’s Saudi-funded programme for “renewing the centre”, faced immediate criticism when he hailed a coup in Bolivia as a triumph of democracy. Today, people can see that petulant rearguardism is being desperately passed off as classical liberalism, that the beneficiaries and propagandists of an exclusionary system have dominated, and infantilised, political and intellectual discourse for too long.

The figures who once claimed authority and expertise find themselves challenged at last, and they won’t persuade many people by holding up their tattered copies of Voltaire and Kant; they are very likely to be told: “Read and think more broadly. Try to learn about other political, literary and philosophical traditions. And don’t forget to take a look at the world you made: it is collapsing around you.” And if they can’t embark on this self-education, they should cede their place to people who are younger, smarter and work harder. For the debacle of a bankrupt intelligentsia and political class is in plain sight. I am not pessimistic, to answer your question, but convinced that very little will change until both are renewed. Unfortunately, the political class is easier to renovate than a resourcefully self-perpetuating intelligentsia.

VTN: If you think that the political class is easier to renovate than the intelligentsia, you actually seem a bit optimistic, or maybe your pessimism about the intelligentsia is simply deeper than your pessimism about the political class. I’ve spent nearly three decades in academia and there is barely a radical left there, despite what Trump and conservatives claim. But academia, at least in the humanities and social sciences, does tilt liberal, and the mainstream liberal intelligentsia in academia is defined by the smugness of the Ivy League, so I think you are right there.

I’m new to the mainstream media world, and have been lucky to work with sympathetic editors, one of whom told me he is happy to periodically throw some of my socialism at the audience of his very mainstream publication.

I was actually invited to sign the Harper’s letter. My gut instinct was to say no, which was compounded by how the person who invited me described the letter as “liberal”. I’m not a liberal, and the refreshing-and-distressing power of social media is that it allows and encourages voices and views that are not liberal. Distressing because really hideous ideas and personalities can flourish there; refreshing because the will to speak truth to power is also strong there. Part of what you imply is that what social media allows is the amplification of non-institutional voices and the creation of whole new personalities. In the worst case, they are “influencers” and “thought leaders”, terms that make me shudder and which are completely implicated in the commodification of the idea as a marketable trend – see the TED talk as exemplary of this – parts of platforms and brands, utterly compatible with liberalism, neoliberalism, cosmopolitanism.

In the best case, these personalities are actually intellectuals. I go back to Antonio Gramsci’s concept of organic intellectuals: organic seems to be the right word to describe how some people outside of the mainstream have been able to use social media to advance ideas. Of course, Trump is organic at handling Twitter too. Contrast him with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who is definitely an organic intellectual at this moment. Whether she remains one or whether she becomes captured by power, we will have to wait and see.

What someone like Ocasio-Cortez or Black Lives Matter represents is the faint hope that the US can save itself from its contradictions. You have cited James Baldwin as a figure who called for an American reckoning with its fatal histories of conquest, war, genocide and slavery.

Not reckoning with these tragedies has, in your argument, left the UK and the US victims of their own ruthless winner-take-all forms of individual capitalism. But strong capitalist dictatorial states such as China have their own problems with the unchecked domination of civil society and minority groups. In the face of China’s rise, it might be that the US has three choices: first, to double down on its current strategy of having a multicultural military-industrial complex that emerges out of a racially and class stratified society whose inequalities pay for the complex. Second, to partly give in to BLM demands and force the nation to finally engage in truth and reconciliation, with reparations and economic redistribution drawn from higher taxes on the wealthy and a relatively small reduction in the Pentagon’s budget. Or third, to greatly reduce the military commitment and transform gracefully into a post-imperial power like Germany, one which is better at taking care of its citizens and defending its interests without seeking global domination.

The last option seems utopian in an American context. The middle option is the best we could hope for in a Biden presidency, and even that seems utopian, except that now at least the idea of reparations is legitimately being discussed by “thought leaders”. But Biden could just as easily slide back into the first option, which is the one Trump is most ferociously committed to, and which has formed the broad parameters of bipartisan consensus in the US for the past few decades. Recounting all this, I remind myself that I’m mostly just someone who finds great pleasure in writing novels, albeit novels that try to confront some of these dynamics.

PM: I suspect these dynamics today point to a treacherous period ahead. The pandemic is still out of control; more lives and livelihoods will be devastated. You cannot rule out a diversionary clash with China, only one of Trump’s likely ruses to postpone his eviction from the White House. And a Biden administration will likely consist of too many people who paved the path to Trump. One source of hope in this bleak scenario is what you call the organic intellectuals.The Guardian

They have no establishment credentials, no supporting networks of self-cherishing elites or rightwing moneybags, and are consequently exposed to vicious attacks. Just look at how dementedly and relentlessly Ocasio-Cortez and Ilhan Omar, two first-time congresswomen, are persecuted today by rightwingers and centrists. But no one should doubt that they are here to stay and to fight and the emancipatory energy released by the BLM protests will fortify them. You can see it working on even older mainstream writers – take, for instance, Hilton Als’ unsparing account of his experiences as a black journalist in a white man’s world. More and more people feel empowered to raise questions they would have not dared to air in the past.

This, in itself, is an immense liberation of souls and minds, and a tremendous expansion of possibilities. I would include with the organic intellectuals those writers of fiction who have known political instability and social injustice with their mother’s milk, and cannot conceive of a literature that excludes this experience. A new book by Eddie Glaude [Begin Again] recounts how Baldwin was seen as a lesser artist after he became more explicitly political. These essentially cold war oppositions between art and politics don’t work any more. The coronavirus has broken the long imperial peace of Anglo-America, and the ideologies and assumptions spawned deep within its self-absorption – whether the end of history or an art perfectly insulated from history – can no longer persuade.

Fresh accounts of how we got here and what we can do are needed. Everywhere you see a young and deeply engaged generation ready to provide them, and what stands in their way are the still formidable forces of a discredited status quo.

VTN: Instead of one step forward, two steps back, I hope what we are seeing now is two steps forward, one step back. Because there will be a step back, a push back. But at the same time, what is crucial about BLM and the massive protests in the streets worldwide is a change in the imagination. We can’t overestimate the power of symbols, ideas, and words, in enabling people to imagine what was once seemingly impossible. Movements drive politicians, intellectuals and writers, but politicians, intellectuals and writers can drive movements, too. Look at the return of Baldwin as a perfect example of this dynamic process between movements and thinkers, someone compelled to action by the civil rights movement and someone whose words now help us understand our present and justify our struggle for the future. No one worries about whether he is a lesser artist now.

For the moment, I choose to hope.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten