Capitalism’s suicidal trajectory can’t be ignored

20 November 2019

If we make it out of the climate emergency, we may come to view the few decades usually described simply as the Cold War that followed the Second World War as halcyon days – at least relative to what we are facing now.

The Cold War was a power struggle between two economic empires for global domination – between the United States and its vassal states, including Europe, on one side, and Russia and its vassal states lumped together into the Soviet Union, on the other. The fight was between a US-led capitalism and what was styled as a Soviet-led “communism”.

That struggle led to an all-consuming arms race, the rapid accumulation of vast nuclear arsenals, the permanent threat of mutually assured destruction (MAD), military bases in every corner of the planet, and the demonisation by each side of the other.

Not much has changed on any of those counts, despite the official ending of the Cold War three decades ago. The world is still on the brink of nuclear annihilation. The arms race is still at full throttle, though it is now dominated by private corporations making profits from “humanitarian interventions” based on “Shock and Awe” bombing campaigns. And the globe is still awash with military bases, though now the vast majority belong to the Americans, not the Russians.

‘End of history’

After the fall of the Soviet Union at the end of the 1980s, we moved from a bipolar world to a unipolar one – where the US had no serious military rival, and where there was no longer any balance of forces, even of the MAD variety.

That was why US empire intellectuals such as Francis Fukuyama could declare boldly, and with so much relief, the “end of history”. The US had won, capitalism had emerged victorious, the west’s ideology had prevailed. Having defeated its rival, the US empire – supposed upholder of democratic values – would now rule the globe unchallenged and benevolently. The dialectics of history had come to an end.

In a sense, Fukuyama was right. History – if it meant competing narratives, diverging myths, conflictual claims – had come to an end. And little good has resulted.

It is easy to forget that the start of the Cold War coincided with a time of intense international institution-building, flowering into the United Nations and its various agencies. Nation-states recognised, at least in theory, the universal nature of rights – the principle that all humans have the same basic rights that must be protected. And the rules governing warfare and the protection of civilians, such as the Geneva Conventions, were strengthened.

In fact, the construction of a new international order at that end of the Second World War was no coincidence. It was built to prevent a third and, in the nuclear age, potentially apocalyptic world war. The two new super-powers had little choice but to recognise that the other side’s power meant neither could have it all. They agreed to constraints, loose and malleable but strong enough to put some limits on their own destructive capabilities.

Carrot and stick

But if these two empires were locked in an external, physical struggle with each other, they equally feared an internal, ideological battle. The danger was that the other side might make a more persuasive case for its system with the opposing empire’s citizens.

In the US, this threat was met with both carrot and stick.

The stick was provided by intermittent witchhunts. The most notorious, led by Senator Joe McCarthy in the 1950s, searched for and demonised those who were considered “un-American”. It was no surprise that this reign of terror, exposing “communists”, focused on the ultimate US myth-making machine, Hollywood, as well as the wider media. Through purges, the creative class were effectively recruited as footsoldiers for US capitalism, spreading the message both at home and abroad that it was the superior political and economic system.

But given the stakes, a carrot was needed too. And that was why corporate capitalism was tamed for a few decades by Keynesian economics. The “trickle-up” effect wasn’t simply a talking-point, as the “trickle-down” effect is now. It was a way of expanding the circle of wealth just enough to make sure a middle class would stop any boat-rocking that might threaten the wealth-elite running the US empire.

War of attrition

The Cold War was a war of attrition the Soviet Union lost. It started to break apart ideologically and economically through the 1980s – initially with the emergence of a trade union-led Solidarity movement in Poland.

As the Soviet empire weakened and finally collapsed, capitalism’s internal constraints could be lifted, allowing Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan to unleash unregulated neoliberal economics at home. That process intensified over the years, as global capitalism grew ever more confident. Unfettered, capitalism anticipated its ultimate fate in 2008, when the global financial system was brought to its knees. The same will happen again soon enough.

Nonetheless, Soviet collapse is often cited as proof of two things: not only that capitalism was a better system than the Soviet one, but that it has shown itself to be the best political and economic system human beings are capable of devising.

In truth, capitalism looks impressive only comparatively – because the Soviet system was appallingly inefficient and brutal. Its authoritarian leaders repressed political dissent. Its rigid bureaucracies stifled wider society. Its paranoid security services surveilled the entire population. And the Soviet command-style economy was inflexible, lacked innovation and regularly led to shortages.

The weaknesses and atrocities of capitalism have been much less obvious to us only because the culture in which we are so steeped has told us for so long, and so relentlessly, that capitalism is a perfect, peerless system based on our supposedly competitive, acquisitive natures.

Installing dictators

History, remember, is written by the victor. And capitalism won. We who live in the capitalist west only hear one side of the story – the one about vanquishing Communism.

We know almost nothing of our own Cold War history: how the US empire cared not a whit about democracy abroad, only about extracting other people’s resources and creating dependent markets for its goods. It did so by cultivating and installing dictators around the globe, usually on the pretext that they were necessary to stop evil “Communists” – often popular democratic socialists committed to redistributing wealth – from taking over.

Think of General Augusto Pinochet, who headed a brutal dictatorship in Chile through the 1970s and 1980s. The US helped him launch a military coup against the democratically elected leftwing leader, Salvador Allende, in 1973. He created a society of fear, executing and torturing tens of thousands of political opponents, so he could introduce a “Shock Doctrine” free-market system developed by US economists that plunged the country’s economy into free-fall. Wealth in Chile, as elsewhere, was siphoned off to a US elite and its local allies.

This catastrophic social and economic meddling was replicated across Latin America and far beyond. In the post-war years, Washington was not just responsible for the terrible suffering its war machine inflicted directly to stop the “Communists” in Latin America and south-east Asia. It was equally responsible for the enormous number of casualties inflicted by its clients, whether in Latin America, Africa, Iran or Israel.

Military-industrial complex

Perhaps the US empire’s greatest innovation was outsourcing its atrocities to private corporations – the emergence of a military-industrial complex Dwight D Eisenhower, the former US army general, warned about in his farewell address of 1961, as he stood down as president.

The global corporations at the heart of the US empire – the arms industries, oil companies and tech firms – won the war of attrition not because capitalism was better, fairer, more democratic or more humane. The corporations won because they were more creative, more efficient, less risk-averse, more psychopathic in their hunger for wealth and power than Soviet bureaucracies.

All those qualities are now unimpeded by the constraints once imposed by a bipolar world, one shared between two super-powers. Global corporations now have absolutely unfettered power to drain the planet of every last resource to fuel a profit-driven, consumption-obsessed system of capitalism.

The truth of that statement was mostly unspeakable 16 years ago when one was ridiculed as a tinfoil-hat-wearing conspiracy theorist for pointing out that the US had invented two pretexts – Iraq’s supposed weapons of mass destruction and its equally imaginary ties to al-Qaeda – to grab control of that country’s oil.

Now Donald Trump, the foolish, brash president of the United States, doesn’t even bother to conceal the fact that his troops are in Syria to control its oilfields.

Toothless watchdogs

The unipolar world that resulted from the fall of the Soviet Union has not only removed the last constraints on the US empire’s war-making abilities, the external battle. It has also had terrible repercussions for the internal, ideological battlefront.

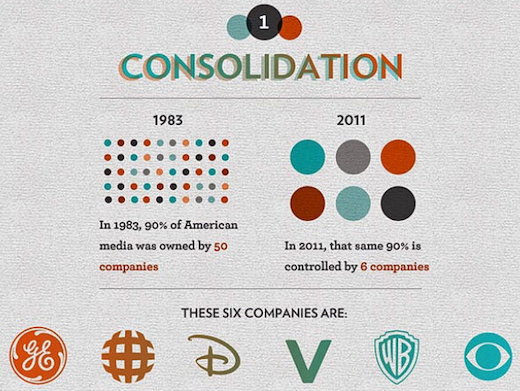

Control of the media has grown ever more concentrated. In the US the flow of information is controlled by a handful of global corporations, often with connections to the very same arms, oil and tech industries so keen to ensure the political climate allows them to continue pillaging the planet unhindered.

For some time I have been documenting examples of the corporate media’s falsehoods in these columns, as you can read here.

But US elites have come to dominate too the post-war international institutions that were created to hold the super-powers to account, to serve as watchdogs on global power.

Now isolated and largely dependent on funding, and their legitimacy, from the US and its European allies, international monitoring agencies have become pale shadows of their former selves, leaving no one to challenge official narratives.

The combined effect of the capture of international institutions and the concentration of media ownership has been to ensure we live in the ultimate echo chamber. Our media uncritically report self-serving narratives from western officials that are then backed up by international agencies that have simply become loudhailers for the US empire’s goals.

A coup becomes ‘resignation’

Anyone who doubts that assessment needs only to examine the reporting of last week’s military coup in Bolivia, which overthrew the democratically elected leader Evo Morales. Corporate media universally described Morales’ ousting and escape to Mexico in terms of him “resigning”. The media were able to use this preposterous framing by citing claims by the highly compromised, US-funded Organisation of American States (OAS) that Morales’ rule was illegitimate.

The Bolivian opposition, @OAS_official, US government and mainstream media manufactured a phony narrative of election fraud, setting the stage for the fascist coup against @evoespueblo. I explain how it happened:

1,777 people are talking about this

Similarly, independent investigative journalist Gareth Porter has shown convincingly how the International Atomic Energy Agency, the body monitoring states’ nuclear activities, has come under the US imperial thumb.

Its inspectors produced gravely misleading information to help the US make a bogus case justifying Israel’s bombing in 2007 of what was claimed to be a secret nuclear reactor built in Syria.

The deceptions, it later emerged, included the IAEA violating its own protocols by concealing the results of the samples taken from the site that showed there was no radioactive contamination. Instead the IAEA highlighted one anomalous finding in a changing-room that was almost certainly caused by cross-contamination from an inspector.

Head-choppers humanised

Another stark illustration of how international agencies have been captured is the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). It has played a central role in bolstering an unproven US narrative, echoed by the western corporate media, that Syrian leader Bashar Assad has been responsible for a spate of chemical weapons attacks on his own people.

That narrative has been vital to western efforts at justifying regime change in a key Middle Eastern state resistant to US-Israeli-Saudi hegemony in the region. The narrative has also been useful in “humanising” the head-chopping extremists of Islamic State and al-Qaeda – which were in control of the areas where these alleged attacks took place – making it easier for the west to support them in a proxy war to oust Assad, a battle that has created untold misery for Syrians.

But the OPCW is no longer the independent, respected expert body it once was. Long ago it fell under effective US control – back in 2003, when its first director-general, Jose Bustani, was forced out by Washington in the run-up to the attack on Iraq. That was when the US needed to manufacture a false pretext for invasion by suggesting that Baghdad had weapons of mass destruction. US official John Bolton even threatened Bustani’s children so desperate was George W Bush’s administration to cow the agency.

In Syria, the post-Bustani OPCW has been the lynchpin of the US narrative spin against Assad. Basic investigative protocols have been discarded by the OPCW, such as the requirement of a “chain of custody” to ensure any samples handed to it can be properly attributed. Instead the OPCW has implicated the Syrian government in the alleged chemical attacks based on samples collected by Islamist extremists desperate to justify more western meddling against Assad to bolster their own rule in Syria.

The first real test of the chemical weapons narrative came last year in Douma, where the Islamists argued that they had again been attacked. That claim led to the US, Britain and France launching missile strikes on Syrian positions in violation of international law.

Days later the Islamists lost control of the city to Assad’s forces and for the first time OPCW inspectors were able to visit the scene of an alleged attack themselves and collect their own samples.

Douma findings distorted

The official report into Douma, published earlier this year, appeared to confirm the US narrative. It hinted strongly that the Syrian air force had dropped two bombs located by the OPCW and that those sites had tested positive for the chemical chlorine.

But thanks to two separate whistleblowers from the OPCW, one of whom was an investigator in Douma, we now know that the official report was not the one submitted by the investigators and did not reflect the evidence they unearthed or their scientific analyses of the evidence. It was rewritten by the OPCW officials in the Hague to suit Washington’s agenda.

The official report was, in fact, a complete distortion of the evidence. Investigators found that levels of chlorine at the supposed bomb sites were no higher than background levels, and less than found in drinking water – nowhere near enough to have killed Douma’s victims shown in photos produced by the Islamist groups.

The investigators’ findings suggested an entirely different narrative: that the Islamists in Douma had placed the bombs at the two sites to make it look like a chemical attack had taken place and thereby provide a pretext for even deeper western interference.

It was not difficult to understand why officials in the OPCW’s head office had decided to conceal their expert inspectors’ findings and submit to US intimidation.

The real findings would have:

- undermined the official narrative unquestioningly attributing the earlier chemical weapons attacks to the Syrian government, in turn making a mockery of western claims to humanitarian concern in aiding and funding years of a devastating proxy war in Syria;

- revealed the politicisation of the OPCW, and the corporate media’s supine treatment of the Islamists’ claims;

- intimated at the collusion between western governments and Islamist groups that have been slaughtering non-Sunni populations in the Middle East and launching terror attacks in the west;

- highlighted that the US-British-French military attack on Syria in response – a violation of Syria’s sovereignty – was not simply a war crime but the “supreme war crime”;

- and bolstered the case for the Syrian government to be allowed to regain control of its territory.

Down the memory hole

The leaks from the OPCW whistleblowers paint a very troubling picture, where our most trusted international institutions can no longer be relied on to seek out the truth. They are there to serve the world’s sole super-power as it seeks to manipulate us in ways that accrete ever more power to it.

Syria narrative managers have been claiming that even if Assad wasn't responsible for Douma, it doesn't matter because he's still bad. But of COURSE it matters, because the mounting evidence that the OPCW was manipulated toward US agendas has immense, far-reaching implications. twitter.com/GeorgeMonbiot/…

158 people are talking about this

It is quite extraordinary that the mounting evidence that OPCW officials conspired in falsifying evidence to help the US empire overthrow another government is not considered news, let alone front-page news. There has been a complete media blackout on these revelations.

In an unguarded moment back in May when she heard about the first whistleblower, the BBC’s much-admired chief international correspondent Lyse Doucet responded to a Twitter follower that it was “an important story” and that she would “make sure programmes know about it”.

Lyse, is it a case that the BBC editorial line is to ignore the leaked @OPCW report or are you personally choosing to? You can't say you aren't aware of it and you can't say the leak hasn't been verified. So what's the reason for your silence? Thanks.

thanks for your message . I am in Geneva today, in Sarajevo and Riga last week, and heading to Gulf next week. It's an important story. Will make sure programmes know about it. As you know,UK outlets focused on May& Brexit last few days.

15 people are talking about this

Six months and another whistleblower later, neither Doucet nor the BBC have uttered so much as a squeak about the discrediting of the OPCW report. This “important story” has been collectively plunged down the memory hole by the corporate media.

In this confected unipolar reality, we the public have been left compass-less, exposed to fake news not only from wayward social media sites or self-interested governments but from the large media “watchdogs” and the very global institutions supposedly set up to act as dispassionate arbiters of truth and justice. We have been returned to a world where might alone makes right.

Environmental destruction

Things are bad enough already, but all the evidence suggests they are going to get a lot worse. Capitalism’s problems go beyond its inherent need for violence and war to acquire yet more territory and open up new markets. Its economic logic is premised on endless growth, based on unremitting resource extraction from a finite planet.

That causes two major problems.

One is that, as the west runs out of resources – most obviously oil – to fuel its endless consumption, resource extraction will become ever more difficult and less profitable. Markets are shrinking and the ramifications can now be felt at home too. Youngsters in the west have no hope of being as successful or wealthy as their parents, or even grandparents.

In a world of diminishing resources and no serious ideological or economic rival, Keynesian economics – the basis on which western elites won over their publics by enlarging the middle class – has been discarded as an unnecessary indulgence. We are in an era of permanent austerity for the many to subsidise the further enrichment of the already fabulously wealthy few.

But second, and much worse, capitalism is being exposed as a suicidal ideology. In its compulsion to monetise everything, it is polluting the oceans with plastic and choking the air with particulates. It is rapidly extinguishing insect life, the main barometer of the planet’s health. It is destroying habitats necessary for larger animals and for biodiversity. And it is creating a climate that humans will soon not be able to survive.

Capitalism isn’t unique in degrading the environment. Soviet economies were quite capable of it too. But as with everything else it touches, capitalism has proved to be uniquely efficient at destroying the planet.

Sinking boat

It is no longer just poor people out of sight in far-off lands who are being made victims of capitalism, though for the time being they are still the worst hit.

They are fleeing the lands we helped to degrade with our weapons, and the crop failures that resulted from the climate change our industries fuelled, and the poverty we increased through our resource grabs and addiction to consumption. But in our continuing arrogance we block their escape with tougher immigration policies and “hostile environment” strategies. We trivialise the plight of those we have displaced through our globe-spanning system of greed as “economic migrants”.

It is gradually becoming clearer – with the environmental emergency – that we are all ultimately in the same boat. It is only the supremely efficient propaganda machine created by the capitalist elite that still persuades too many of us that there is no way to get off the boat. Or that if we try, we will drown.

But the stark reality is that we are in a sinking boat – the sinking boat of capitalism. The hole is growing and water rushing in faster by the day. Inaction means certain death. It is time to be brave, open our eyes and search for dry land.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten