THE ANGRY ARAB: Armies & Politics in the Middle East

As`ad AbuKhalil reviews Middle East rulers’ reasons for distrusting

their own militaries.

King Hussein of Jordan among his troops, March 1957. (Wikimedia Commons)

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

Special to Consortium News

A close association between armies and politics has pertained in the Middle East for a long while. Army leaders have led many Arab countries in contemporary times. In Israel, prime ministers are often drawn from the ranks of former generals or commanders. Shimon Peres, for instance, was a director-general of the Israeli Defense Ministry and he played a key role in Israeli acquisition of nuclear weapons through devious and deceptive means that violated international laws and the laws of many countries, including the U.S.

A close association between armies and politics has pertained in the Middle East for a long while. Army leaders have led many Arab countries in contemporary times. In Israel, prime ministers are often drawn from the ranks of former generals or commanders. Shimon Peres, for instance, was a director-general of the Israeli Defense Ministry and he played a key role in Israeli acquisition of nuclear weapons through devious and deceptive means that violated international laws and the laws of many countries, including the U.S.

In Israel, the military has been romanticized and glorified and Israeli chiefs-of-staff are often expected to run for high office as soon as they retire from the military. The public in Israel has always sought leaders who can promise — and deliver — mass violence on the Arab population and the ability to impose Israeli will by force. Israeli top generals exemplified the doctrine of mass violence which served as one of the founding elements of state Zionism.

The Israeli war crimes against the native Palestinian population have created a special place for Israeli military commanders, and has in fact militarized the entire Israeli society. This militarization is seen as heroic here in the U.S. (even liberals swoon when Amos Oz would talk about his role in various Israeli wars), and for Arabs it has made it unfortunately difficult to distinguish between military and civilian targets in Israel, where all adults are expected to serve in the army (non-Druze Arabs are not permitted except in some cases while students of Jewish religious seminaries are exempted from service).

The entry of Arab armies into Arab politics began in earnest after the occupation of Palestine in 1948. Armies launched coups in Egypt, Syria and Iraq (three in Syria in one year alone in 1949, two of which were probably engineered by U.S. intelligence) and often in the name of helping the Palestinians return to their homeland. [For more on this, see Patrick Seale’s “The Struggle for Syria,” and Hugh Wilford’s “America’s Great Game: The CIA’s Secret Arabists and the Making of the Modern Middle East.”]

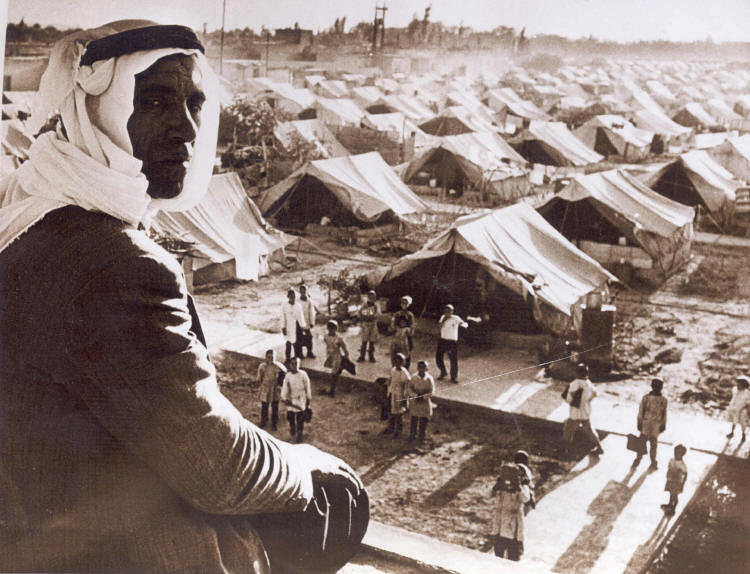

Jaramana Refugee Camp in Damascus, Syria, established after the “catastrophe” known as Nakba, 1948. (Wikimedia Commons)

‘Palestine’ in Coup Lingo

Coups in Sudan, Libya, and Yemen also invoked the name of Palestine, as did coups that failed, as the Al-Watha’iq Al-Arabiyyah documentary anthology for 1969 and 1970 details. “Palestine” became a word used for political rationalization and legitimization by seekers of political power. All new regimes had to offer a promise or a vague plan for the liberation of Palestine. Syrian President Amin Hafiz, in office during the 1960s, even announced that he was willing to liberate Palestine in a matter of hours.

In the 1950s and 1960s (up until the devastating 1967 defeat), Arabs were made to expect that a battle could erupt any minute now and that it will be the final blow which will bring the Zionist state down. But the 1967 defeat dashed the hopes of the people, and it erased the prestige that Arab people have bestowed —rather unfairly — on Arab armies. Military expenditure was justified in the name of liberating Palestine but the abysmal performances on the battle field exposed the militaries as either tools of corrupt regimes or as instruments of local repression, or often vehicles of Western political machinations and intrigue.

The military has been tainted in Arab politics and rulers don’t trust the military anymore. In the Gulf, the military is an important element of political power but the regimes don’t trust them in the hands of strangers, i.e. commoners. Relatives (usually brothers or half-brothers) of the rulers run the military and intelligence apparatuses. Rulers’ utmost care towards the military apparatus has led them to attain military degrees to project an image of military expertise. This started with King Husayn of Jordan, who attended the U.K.’s Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. After him, most Gulf regimes sent sons and nephews of the rulers to Sandhurst. (Arab royals don’t undergo the regular military degree-issuing program, but special training is arranged for them and presumably for large sums of royal donations).

In Arab republican regimes such as Iraq and Syria, the rulers have also assigned members of the family to key military and intelligence assignments. This was the case under Saddam in Iraq and also under Hafidh Al-Asad, the former president of Syria. It may have been reduced under Bashar, Syria’s current ruler, but only due to the death of his brother-in-law. And Bashar’s brother, Maher, still commands The Fourth Armored Division.

Egypt’s Road to Revolt

Hazem Qandil, in his excellent recent book, “Soldiers, Spies, and Statesmen: Egypt’s Road to Revolt,” sheds new light on the nature of the relationship between the ruler and the military. He maintains that Gamal Abdel Nasser lost all his control over the Egyptian army as soon as `Abdul-Hakim `Amer was put in charge after the 1952 revolution. Amer would continue to exercise supreme control over the armed forces until the devastating 1967 defeat, which was largely of his own making. Nasser took control of the army in 1967 until his death in 1970. During that time, Nasser restructured the army, professionalized it and distanced it from political affairs by drastically reducing the number of former military people in the Egyptian cabinet.

Hazem Qandil, in his excellent recent book, “Soldiers, Spies, and Statesmen: Egypt’s Road to Revolt,” sheds new light on the nature of the relationship between the ruler and the military. He maintains that Gamal Abdel Nasser lost all his control over the Egyptian army as soon as `Abdul-Hakim `Amer was put in charge after the 1952 revolution. Amer would continue to exercise supreme control over the armed forces until the devastating 1967 defeat, which was largely of his own making. Nasser took control of the army in 1967 until his death in 1970. During that time, Nasser restructured the army, professionalized it and distanced it from political affairs by drastically reducing the number of former military people in the Egyptian cabinet.

After Nasser’s death, Anwar Sadat isolated the army and assigned the police and the Ministry of Interior key roles in government and in imposing internal repression. Sadat feared that the army would become too powerful and would rival his authority, as it had done under Nasser. Ever since, the Egyptian army has become weak politically (until recently) and entirely subservient to the political leadership. During and after the 1973 war Sadat made sure to taint the reputation of every war hero out of fear of political competition. Sadat turned the defeat of 1973 into a victory (as did the Syrian regime) and took full credit for the ostensible victory.

Husni Mubarak followed in the footsteps of Sadat, and both relied on the U.S. to provide all the instruments and equipment of repression, while the Egyptian army was permitted to obtain only those weapons that are licensed by the Israeli lobby in D.C. [See Edward Tivnan here on AIPAC approving and disapproving of sales.] Only once did Mubarak feel threatened by an Egyptian commander-in-chief (and defense minister), `Abdul-Halim Abu Ghazalah, who was dismissed from his post in 1989 when his aura started to eclipse that of the Egyptian president.

Algerian protesters, March 10, 2019. in Blida. (Fethi Hamlati, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

But the Arab armies may, in some cases, be independent in their interests from those of the rulers. The recent uprisings in Algeria and Sudan demonstrated that the army may act against a ruler if it feels that his preservation in power is posing a threat to the interests of the military-intelligence apparatus.

Let us also remember that the military-intelligence apparatus in the region is almost entirely beholden to the U.S., which funds, trains and equips almost all Middle East militaries (except Syria and Iran) in the name of fighting “terrorism” but also for purposes of internal repression, which suits U.S. interests. When Egyptian masses stormed the Israeli embassy in Cairo in 2011 after the eruption of the popular uprising, Israeli Mossad agents (referred to as “security staff” by some press) were stuck inside the building. Under U.S. and Israeli pressure, Egyptian troops at the embassy were deployed to save them. The U.S. invests in regimes and not in individuals — notwithstanding the high praise U.S. officials often give to Middle East despots.

Armies in the Middle East continue to wield great influence and political power because the U.S. regional hegemony schemes require the utilization of loyal local troops who can assist the U.S. in its various wars and military interventions. The militaries were the place from which Arab leaders emerged, and now they are mere tools in the hands of the leaders in the Gulf, and they are sometimes more powerful than the leader in republican regimes. This gave Mohammad Morsi’s presidential election its pyrrhic quality. Had he moved quickly to purge the top ranks of the Egyptian military, the U.S. would have stopped him. But doing so was the only way he might still have been president today.

As’ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the “Historical Dictionary of Lebanon” (1998), “Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), and “The Battle for Saudi Arabia” (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten