Ignorance now rules the U.S. Not the simple, if somewhat innocent ignorance that comes from an absence of knowledge, but a malicious ignorance forged in the arrogance of refusing to think hard about an issue. We most recently saw this exemplified in Donald Trump’s disingenuousness 2019 State of the Union address in which he lied about the amount of drugs streaming across the southern border, demonized the immigrant community with racist attacks, misrepresented the facts regarding the degree of violence at the border, and employed an antiwar rhetoric while he has repeatedly threatened war with Iran and Venezuela. Willful ignorance reached a new low when Trump — after two years of malicious tweets aimed at his critics — spoke of the need for political unity.

Willful ignorance often hides behind the rhetoric of humiliation, lies and intimidation. Trump’s reliance upon threats to impose his will took a dangerous turn given his ignorance of the law when he used his speech to undermine the special council’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election. He did so with his hypocritical comment about how the only things that can stop the “economic miracle” are “foolish wars, politics or ridiculous partisan investigations,” to which he added, “If there is going to be peace and legislation, there cannot be war and investigation.” According to Trump, the Democrats have a choice between reaching legislative deals and pursuing “ridiculous partisan investigations” — clearly the country could not do both.

William Rivers Pitt is right in claiming that in one moment Trump thus tied “the ongoing Robert Mueller investigation inextricably to terrorism, war and political dysfunction.” As Mike DeBonis and Seung Min Kim point out, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi added to this criticism by “accusing Trump of an all-out threat to lawmakers sworn to provide a check and balance on his power.”

Malicious ignorance is a willful refusal to reflect enough to do justice to the complexity of an idea and its potential consequences. This is a kind of ignorance that combines the mindset of tyrants with a notion of unreflective certainty that banishes doubt and views opposing positions as acts of treason that are often deserving of some kind of punitive action. Unfortunately, we live at a moment in which ignorance appears to be one of the defining features of U.S. political and cultural life. Ignorance has become a form of weaponized refusal to acknowledge how the violence of the past seeps into the present, reinforced by a corporate-controlled media and digital culture dominated by fatuous spectacles and consumerist trivia.

In the age of Trump and the rise of illiberal democracies all across the globe, James Baldwin was certainly right in issuing in No Name in the Street the stern warning that “Ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.” Trump’s ignorance lights up the Twitter landscape almost every day. He denies climate change along with the dangers that it poses to humanity, shuts down the government because he cannot get the funds for his wall — a grotesque symbol of nativism — and heaps disdain on the heads of his intelligence agencies because they provide proof of the lies and misinformation that shapes his love affair with tyrants. This kind of power-drunk ignorance is comparable to a bomb with a fuse that is about to explode in a crowded shopping center. This dangerous type of ignorance fuses with a reckless use of state power that holds both human life and the planet hostage.

Ignorance in a Culture of Immediacy

It sometimes feels as if the age of big ideas has come to an end, transformed into a scattered set of cultural spheres that reinforce the elevation of ignorance to a national ideal and form of weaponized politics. For example, culture has been turned into a disimagination machine that prioritizes a culture of metrics and the hypnotic seductions of the screen. (It’s no coincidence that Trump is the first president whose main source for understanding the world and generating policies is the television.)

Americans live in a culture of immediacy that has created new forms of social and historical ignorance and erasure. As writer John Gray points out, disparaging the past has become “a mark of intellectual respectability.” He then reinforces the point by quoting literary critic Francis O’Gorman, who argues that in the current age marked by “a revival of intolerance” it has become “easier to affirm elements of a Nazi ideology recast in versions of white supremacy.” What Gray was rightfully suggesting, often missed by many progressive commentators, is that fascism never confined itself to the past and is now winning ideologically on a new kind of battlefield.

Time no longer has a long durée; it has to be instantaneous, pulsating with information that barely adds up to a sustained idea. Time is now connected to short-term investments and quick financial gains, defined by the nonstop and frenetic perpetuation of an impoverished culture of global exchange. Time is no longer connected to long-term investment in community, the development of social well-being, and goals that benefit young people and the common good. Time has become a burden more than a condition for contemplation.

The flow of money now replaces the flow of thoughtfulness, critical dialogue and informed judgment. This is exacerbated in a culture of immediacy in which instant gratification rules and thoughtful contemplation becomes a thing of the past. Long-term investments have given way to short-term investments, and in doing so, have erased any long-term commitments to valued relationships, young people, intimacy, justice and compassion. Barbarism presents itself in acts, experiences and forms of suffering that vanish from the mainstream media as quickly as they appear.

The language of neoliberalism erases any notion of social responsibility, and in doing so, eliminates the belief that alternative worlds can be imagined. Under the Trump administration, the world of the robust imagination, a vibrant civic literacy, and inspiring and vitalizing ideas are turned into ashes. Ignorance, forgetfulness and cruelty now merge into a notion of common sense that sustains the willful ignorance of the rich and powerful. How else to explain Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross stating during the shutdown, when thousands of federal workers missed their paychecks, that he did not understand why some of them were visiting food banks or seeking food assistance when they could be taking out loans.

This is a form of ignorance that morphs into a culture of cruelty, one that is all too apparent as part of larger mechanisms of power and violence in the United States. As civic culture disappears, historical memory is broken, and words such as fascism, nativism, genocide, internment, war and violence appear as empty abstractions, only to be trivialized or dismissed in the 24-hour news cycle now driven by Trump’s Twitter convulsions.

Life Under Neoliberal Authoritarianism

In the current historical moment, there is a growing worldwide rejection of liberal democracy. We live in an age in which a distinctive form of authoritarianism has emerged which fuses the toxic austerity policies and ruthless ideologies of neoliberalism with the racist and ultra-nationalist principles and attitudes of a fascist past. What might be called a state-manufactured grammar of violence, white supremacy and ignorance no longer hides in the shadows of power and ideological deception. It is now displayed as a nativist badge of honor by right-wing politicians and pundits such as Steve Bannon.

Not only is authoritarianism and the expanding architecture of violence on the rise in countries such as Poland, Hungary, India and Turkey, it is also on the rise in the United States — a country that has prided itself, however erratically, on its longstanding commitment to democratic rights. Democratic institutions, relations, values, principles and passions are under siege both by the vicious forces of neoliberal capitalism and by the forces of white supremacy and ultra-nationalism, which have been given a new life in the resurgent elements of fascism, albeit in updated forms.

What must be remembered is that fascism is not a static ideology rooted in a particular moment in history. The conditions that produce torture chambers, intolerable violence, extermination camps, a politics of disposability and racial cleansing are still with us and cannot be easily dismissed as a relic of the past. As Hannah Arendt, Sheldon Wolin, Umberto Eco and others have observed, the ghosts or warning signs of totalitarianism are crystalizing in new forms and now herald a possible model for the future.

Racial hatred, war, a contempt of dissent, disdain for education, the dismantling of the welfare state, the celebration of civic illiteracy, and the use of state violence against immigrants, Muslims and people of color have become normalized in many countries including the United States. Moreover, there is also a systemic erosion of civic culture and any sense of shared citizenship, not to mention a full-fledged attack on the ecosystem in the name of pillaging the planet for financial gains.

Under neoliberal capitalism, there are no commanding ethical visions. The public has collapsed into the private, and a culture of self-absorption appears fully attuned with a growing aesthetics of vulgarity that thrives on a celebrity culture of ignorance that wields enormous authority, and merges with a spectacle of violence that disingenuously presents itself under the banner of mass entertainment. As neoliberal societies produce massive levels of inequality in wealth, power and income, they increasingly legitimate themselves through a culture of fear, state violence and hyper-consumerism that empties politics of any meaningful relationship to a broader public.

A morbid inequality now shapes all aspects of life in the United States. Three men — Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett and Bill Gates — have among them as much wealth as the bottom half of U.S. society. In a society of pervasive ignorance, such wealth is viewed as the outcome of the actions and successes of the individual actors. But in a society in which civic literacy and reason rule, such wealth would be considered characteristic of an economy appropriately named casino capitalism. In a society in which 80 percent of U.S. workers live paycheck to paycheck, and 20 percent of all children live below the poverty line, such inequalities in wealth and power constitute forms of domestic terrorism — that is, state-initiated violence or terrorism practiced in one’s own country against one’s own people.

State violence has been intensified around the globe in its suppression of dissent, killing of journalists, scapegoating of minorities and the use of militarized polices forces. In addition, the substance of politics is increasingly undermined in a mood economy in which the language of therapy, self help and self-transformation has exploded under a neoliberal regime that claims that the personal is the only politics there is. The self is now cut off from any sense of common purpose and solidarity, if not social and political responsibility. As the language of community, civic culture and crucial public spheres collapse, people are increasingly atomized and rendered powerless, and more than willing to believe that they have little control over their lives.

As I have analyzed in my book American Nightmare, under the banner of a fascist politics, political extremists such as Donald Trump have taken this sense of anger, anxiety and helplessness, and used it to tell their supporters that they should be angry about Black people, immigrants, Muslims, and a host of other groups that have nothing to do with the economic and existential problems that the majority of the population faces daily.

The Role of Violence in Contemporary Life

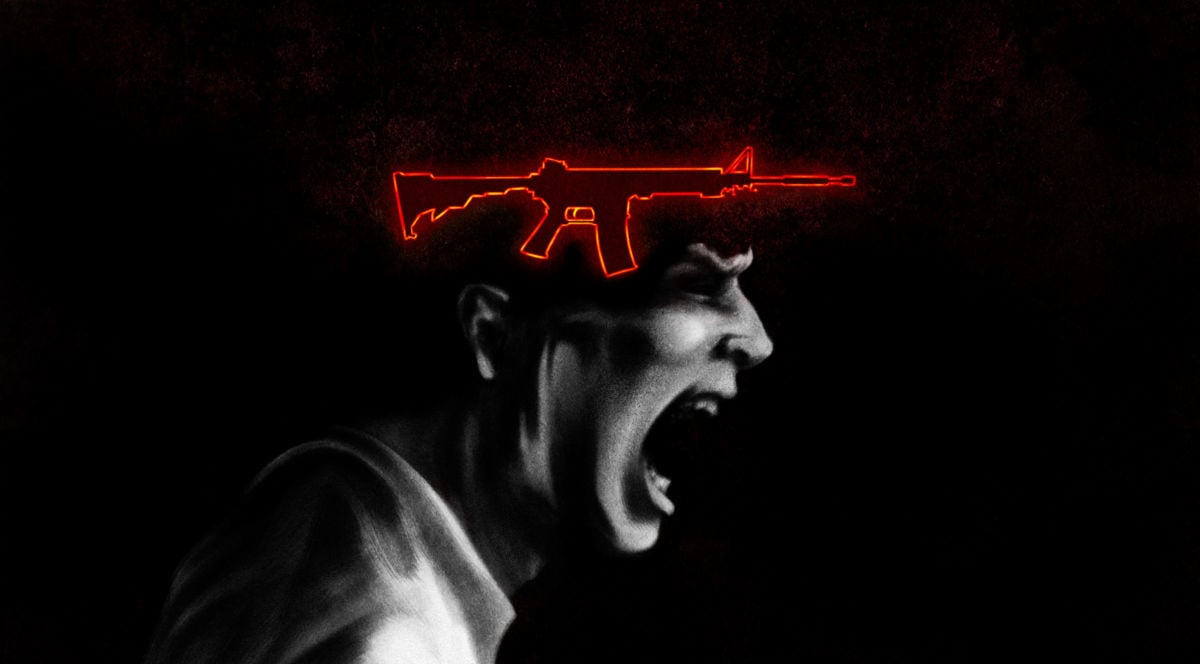

What has become increasingly clear in the United States is that an emerging fascist politics produces a new kind of carnage that is marked by escalating poverty and misery among large sections of the public. This carnage is coupled with the relentless violence manifested in an epidemic of social isolation, an opioid crisis, mass shootings, the growing presence of the police in all public spheres, and a culture of fear that strengthens the security state and diminishes the welfare state.

Violence has moved from a tool of terror and punishment to a dangerous political space in the wider culture that signals both the loss of historical memory, and a flight from reason and morality. Violence is now both incremental and explosive, dispersed and immediate, but in both cases it is increasingly normalized as it moves between the symbolic and real life.

This is a violence stretched across multiple landscapes and functions as both an attritional violence that is difficult to see and a spectacularized violence all too visible in its catastrophic effects. The deep-seated grammar of violence at work in U.S. society with its slow-motion toxicity is often lost in those forms of violence that are fully exhibited in a televisual digital culture. The visceral and the eye-catching now commands our attention while the slow-burning violence that hides beneath the made-for-TV violence of fiery hot forests, volcanoes, earthquakes and mass shootings remains unnoticed.

We now struggle to perceive structural and systemic violence behind the exhibition of “toxic imagery” that venerates the spectacle and conceals the conditions that degrade human life. Is it any wonder that notions of collective responsibility have been replaced by a collective numbing that collapses the line between a genuine moral crisis and the fog of ethical indifference? As Brad Evans makes clear in Atrocity Exhibition, this is a violence that is as existential as it is visceral. There is nothing abstract about the subject of violence, especially under the leadership of a growing number of authoritarian leaders, with Trump at the front of the line, who enable and legitimate it.

The paramount role of violence in many countries today raises questions about the role of the university, academics and students in a time of tyranny. Equally so, it raises crucial questions about the centrality of education to politics and especially how the wider culture functions pedagogically to produce particular kinds of agents, desires, identifications and modes of agency either in support, or at odds with, democratic values and social relations. The latter opens up new questions regarding how we think about the very terrain of politics.

How might we imagine education as central to politics whose task is, in part, to create a new language for students, one that is crucial to reviving a radical imagination, a notion of social hope and the courage to collective struggle? How might higher education and other cultural institutions address the deep, unchecked nihilism and despair of the current moment? How might higher education be persuaded to not abandon democracy, and take seriously the need to create informed citizens capable of fighting what Walter Benjamin once called the “illumination” of fascism and its swindle of fulfillment? As American studies professor Christopher Newfield argues, “democracy needs a public” and higher education has a crucial role to play in this regard as a democratic public good rather than defining itself through and primarily within the culture of business and the values of the financial elite.

Current discourses about fascism often point to the assumptions that drive its politics in its current and diverse forms. What is not often mentioned is the formative culture that gives it meaning, creates the subjects who identify with its toxic worldview, and shapes the desires it mobilizes as part of a larger set of assumptions about the future and who shall inherit it. If we are to expand these important considerations, it is crucial to address how culture and education are intimately connected with social relations rooted in diverse class, racial, economic and gender formations.

To do so we must connect the domains of meaning and representation with the development and functioning of institutional forms of power, especially what might be called the rise of commanding cultural apparatuses that mark a distinctive form of public pedagogy in the current historical moment. Moreover, we need to rethink how culture is not only marked by different sites of struggle, but also how such struggles take place around and over language, values and social relations within the institutions that organize them, extending from public and higher education to the mainstream media to the expansive world of digital culture.

Insisting That Radical Change Can Happen

In an age when culture works to depoliticize, consumerize and privatize, the spaces available for cultural workers to engage in critical pedagogical work that makes power visible are under siege. Yet, it is precisely such spaces where power can be challenged through the use of radical educational and pedaogogical practices that can be used to translate private issues into broader social considerations. These spaces support the production of persuasive alternative ideas, modes of identification, critical forms of agency and courageous forms of political action.

Under Trump, the assault on free speech and dissent has been widely recognized. Less is said about the broader and more pernicious use of language in the service of violence, and how it carries the potential for producing world views that align with the meanings and discourse of a fascist past. No one who believes in a radical democracy can remain numb and silent in the face of the merging of ignorance and power in a language that dares to celebrate the horrors of the unspeakable.

John Dewey, Václav Havel and others have long warned us that a simplistic faith in the stability of the institutions in which a democracy is grounded will automatically prevent the emergence of authoritarianism. But authoritarian societies are not just the result of bad governance. They emerge from a more fundamental deformation in the culture itself. That is, democracy’s survival depends on a formative culture whose strength lies in a set of habits and dispositions rooted in a civic culture and a civic literacy capable of sustaining it.

The deep-seated habits of cruelty, greed, consumerism, racism and unchecked individualism at the heart of neoliberal fascism are eroding the social fabric that make a democracy possible. Coercion, fear and repression are not the only tools used by authoritarian societies. Matters of value, identity, agency and the habits of solidarity when in crisis are as threatening to a democracy as are the forces of repression. Ignorance is the mortar and building blocks of fascism. Politics follows culture, and this means that an informed public is central to any democracy. Being informed is a habit of democracy that supports a broader understanding of how education and the institutions that sustain it can be protected.

We live in dangerous times and there is an urgent need for more individuals, institutions and social movements to come together in an effort to construct a new political and social imaginary. We must support each other in coming to believe that the current regimes of tyranny can be resisted, that alternative futures are possible and that acting on these beliefs will make radical change happen.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten