The Secret Saudi Ties to Terrorism

Exclusive: Saudi Arabia, working mostly through Israel’s Prime Minister Netanyahu, is trying to enlist the U.S. on the Sunni side of a regional war against Iran and the Shiites. But that alliance is complicated by Saudi princes who support al-Qaeda and other Sunni terrorists, as Daniel Lazare explains.

The U.S.-Saudi alliance is coming under unprecedented strain. Everything seems to be going wrong. Up in arms over growing Shi‘ite resistance in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Bahrain and Yemen, the ultra-Sunnis in Riyadh are alarmed that Obama continues to press ahead with arms negotiations in Teheran, from its viewpoint the center of the Shi‘ite conspiracy.

Saudis want the U.S. to overthrow Syria’s Assad in return for its cooperation in the fight against ISIS, yet Washington is signaling that it wouldn’t mind if the Baathists remain in power in Damascus a while longer. Similarities between Saudi methods and those of the Islamic State – both have a peculiar fondness for beheadings – are harder and harder to ignore. But with Saudi executions now running at triple the 2014 rate according to Amnesty International, the Saudis are pressing on regardless.

Even the kingdom’s decision to award a $200,000 prize to an Indian tele-preacher named Zakir Naik for “services to Islam” seems like a deliberate thumb in the eye of the United States. Naik, who has been banned from entering Canada or the U.K., is a Salafist nightmare who attacks evolution, defends al-Qaeda, and claims that George W. Bush was secretly responsible for 9/11. What is Riyadh’s point other than to flip Washington the bird?

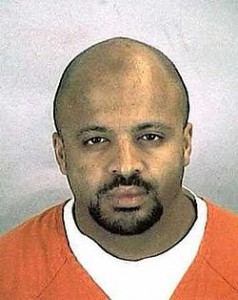

But the ultimate body blow may prove to be Zacarias Moussaoui’s sensational testimony in an anti-Saudi lawsuit filed by 9/11 survivors. Now serving a life sentence in a federal supermax prison in Florence, Colorado, Moussaoui, the so-called “twentieth hijacker,” told lawyers about top-level Saudi support for Osama bin Laden right up to the eve of 9/11 and even a plot by a Saudi embassy employee to sneak a Stinger missile into the U.S. under diplomatic cover and use it to bring down Air Force One.

Moussaoui’s list of ultra-rich al-Qaeda contributors couldn’t be more stunning. It includes the late King Abdulllah and his hard-line successor, Salman bin Abdulaziz; Turki Al Faisal, the former head of Saudi intelligence and subsequently ambassador to the U.S. and U.K.; Bandar bin Sultan, a longtime presence in Washington who was so close to the Bushes that Dubya nicknamed him Bandar Bush; and Al-Waleed bin Talal, a mega-investor in Citigroup, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, the Hotel George V in Paris, and the Plaza in New York.

These are people whom a series of U.S. presidents have fussed and fawned over – not just Bushes I and II, but Obama, who bowed deeply at the waist upon meeting Abdullah in April 2009. Yet according to Moussaoui, the princes provided bin Laden with millions of dollars needed to engineer the deaths of nearly 3,000 people in Lower Manhattan.

Considering how 9/11 has driven U.S. foreign policy, then the consequences are staggering. Teapot Dome? Watergate? If Moussaoui’s story turns out to be true, then the latter will really seem like the “third-rate burglary” that Nixon always made it out to be.

An Inside View

So the first question to ask concerns Moussaoui credibility. Should we believe the guy? How credible is he? The short answer is: very.

Admittedly, Moussaoui is a nut job whose behavior during his trial in U.S. federal court was often bizarre. He refused to enter a plea, tried to fire his court-appointed attorneys, filed a motion describing the presiding judge as a “pathological killer … with ego-boasting dementia,” and described the U.S. as “United Sodom of America.”

But as the New York Times points out, Judge Leonie M. Brinkema said she was “fully satisfied that Mr. Moussaoui is completely competent,” adding that he is “an extremely intelligent man” with “a better understanding of the legal system than some lawyers I’ve seen in court.”

In his testimony last October – the transcripts of which became public early last month – he comes across as calm and lucid, a man eager to tell what he knows about bin Laden’s terror operation and its connections with the uppermost rungs of Saudi society.

What’s more, what he has to say is highly plausible. His account not only accords with what we know about Saudi Arabia’s otherwise opaque power structure, but seems to shed light on a few things we don’t.

The most obvious concerns Saudi Arabia’s 7,000 or so princes and their riotous lifestyle. The kingdom is famous for banning alcohol, virtually all types of public entertainment, and the slightest sexual displays. Yet its over-paid, under-worked royals are no less notorious for stampeding to the airport cocktail lounge as soon as they touch down in Cairo or Dubai and then jetting off to the plushest casinos and brothels that Europe has to offer.

So if mullahs can’t tolerate the sight of a woman’s bare arm, then why do they put up with such licentiousness? The answer, according to Moussaoui, is that the ulema, as the mullahs are collectively known, does so because of the leverage it gains.

“Ulema, essentially they are the king maker,” he testified. “If the ulema say that you should not take power, you are not going to take power.”

Since the mullahs have the power to label as an apostate anybody who drinks, fornicates (i.e. engages in illicit sex), or practices homosexuality – collective behavior which apparently covers virtually the entire royal family – then the effect is to give the ulema a veto over who is eligible for the throne and who is not. The more the princes misbehave, the more control the ulema acquires over Saudi politics as a whole.

Another puzzle concerns why the Saudi establishment would continue channeling funds to bin Laden even after a war of words had broken out over the stationing of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia during the 1990-91 Gulf War. Former CIA counter-intelligence chief Robert Grenier has seized on the issue to discredit Moussaoui’s testimony out of hand.

“The reason Osama bin Laden went to Sudan in the 1990s in the first place was because he was under pressure from the Saudi government,” Grenier told the Guardian. “The idea they’d be supporting him under any circumstances, and in particular in an attack on the U.S., is inconceivable.

But Moussaoui’s version is more nuanced than Grenier’s rather self-serving description of the Saudis as reliable partners would suggest. When asked why Saudi princes would contribute to someone who had turned against them, Moussaoui replied that bin Laden had not turned against all of the princes, merely some of them:

“He went against Fahd, but he didn’t want to go against … Abdullah Saud and Turki and the people who have been classified by … the ulema as … criminal, but not apostate.”

The mullahs, no less xenophobic than bin Laden, despised then-King Fahd because he had OK’d the stationing of U.S. troops in “the land of the two holy mosques.” But while Abdullah was also guilty of certain offenses according to the ulema – hence Moussaoui’s description of him as a “criminal” – they did not add up to apostasy, or abandonment of Islam, a far more serious offense.

The mullahs were therefore willing to cut him some slack, according to Moussaoui, in the hope that he would steer the kingdom back in a more authentically Muslim direction. “[T]he ulema told him [bin Laden] not to wage war against Al Saud,” Moussaoui said, “because Fahd was going to die and therefore that Abdullah Al Saud will take power and he will reestablish a true power.”

If we accept Moussaoui’s description of the mullahs as kingmakers, then this makes sense. As to why the princes would funnel aid to bin Laden as opposed to some other would-be terrorist mastermind, Moussaoui is helpful as well. Post-9/11, Bandar bin Sultan dismissed bin Laden as a flaky no-account who “couldn’t lead eight ducks across the street.”

But in his testimony, Moussaoui describes bin Laden as a capable organizer who built a complicated jihadi movement from the ground up. Since holy war is expensive, he was dependent on large-scale infusions of cash and equipment. As Moussaoui put it in his less-than-perfect English:

“[A]ll this money were there … especially to set up the camp, because nothing was there, it was the desert, so we have to pay Afghan to dig a well, you have to dig to build the base for tent and camp and medical, everything was created from scratch, it was very expensive, OK? … I mean, hundred of thousand of dollar on a weekly basis, you know? You have a lot of car, you have to pay for the maintenance of the tank and dozer, OK, and all of the spare part. … And everybody would get expense … every child have X amount of money, every woman have X amount of money, every person have X amount of money … a quite substantial [amount] of money.”

Since 9/11 was nothing if not smoothly organized, Moussaoui’s description of bin Laden as a skilled operator makes sense as well. Moussaoui notes that bin Laden stood high in the religious establishment’s esteem, much higher, in fact, than the princes.

Bin Laden’s father, the Yemeni-born construction magnate Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden, had been best friends with Saudi Arabia’s founding king, Ibn Saud, and had been entrusted with rebuilding or restoring Islam’s three holiest sites – the Grand Mosque in Mecca, the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, and the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

Since Mohammed bin Laden was pure gold in the eyes of the ulema as a consequence, Osama was 24-karat as well. “So bin Laden was pure,” Moussaoui said, “a pure Wahhabi [who] will obey the Wahhabi scholar to the letter” – loyalty that the mullahs fully repaid.

When asked what Abdullah, Turki and other top-rank royals hoped to get in exchange for contributing to bin Laden’s organization, Moussaoui replied that “it was a – a matter of survival for them, OK, because all of the mujahideen … the hard core believe that … Al Fahd was an apostate, so they would have wanted jihad against Saudi Arabia.”

If Wahhabi hardliners believed that Fahd was a renegade, then they might say the same of other high-living royals, in which case the princes would have to run for their lives. Funding bin Laden was a cheap way to remain in the mullahs’ good graces and continue raking in profits.

Real Power behind the Throne

Bin Laden was thus the ulema’s fair-haired boy, and since the princes were already skating on thin ice, they had to be nice to him so that the mullahs would be nice to them in return. Referring to top Wahhabi theologians Abd al-Aziz ibn Baz and Muhammad ibn al Uthaymeen, Moussaoui said:

“He [bin Laden] was doing it [waging jihad] with the express advice and consent and directive of the ulema. He will not have a single persons coming from Saudi Arabia if the ulema and Baz or Uthaymeen state this man is wrong. … Not to say he’s an apostate … just he’s wrong … everybody will have left, except the North African maybe.”

One word from the mullahs and bin Laden would have found himself cut off – or so Moussaoui maintains. If talk of an all-powerful ulema seems a mite over the top, other experts agree that their clout is difficult to exaggerate.

Mai Yamani, an independent scholar who is the daughter of the famous Saudi oil minister Ahmed Zaki Yamani, describes the Wahhabis, for instance, as “the kingdom’s de facto rulers,” noting that that they control not only the mosques and religious police, but all 700 judgeships, religious education in general (which comprises half the school curriculum), and other ministries as well.

While the House of Saud has proved adept at co-opting the mullahs and keeping in their place, decades of oil money have resulted in a hypertrophied religious sector to which attention must be paid. [See Thomas Hegghammer, Jihad in Saudi Arabia: Violence and Pan-Islamism since 1979 (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010), pp. 232-33]

So princes tread lightly in the ulema’s presence. This seems to have been especially the case during the delicate post-1995 period when Fahd continued to cling to the throne even though crippled by stroke and Abdullah ruled in all but name. One king was out, but the other was not yet in, which is why the religious establishment’s approval was more critical than ever.

Thus, the princes eagerly did the ulema’s bidding, funding bin Laden’s activities abroad and only putting their foot down, according to Moussaoui, when it came to jihad at home. While Osama was free to do what he liked in Afghanistan and elsewhere, the princes drew the line at “do[ing] stuff in your … backyard.”

Moussaoui, who says he was put to work compiling a financial database upon joining al Qaeda in late 1998, describes flying by private plane to Riyadh as a special courier.

“We went in … to a private airport,” he recalled. “[T]here was a car, we get into a car, a limousine, and I was taken to a place, it was like a Hilton Hotel, OK, and the next morning … Turki came and we went … to a big room, and there was Abdullah and there was Sultan, Bandar, and there was Waleed bin Talal and Salman” – i.e., the Saudi crème de la crème. When asked if the princes knew why he was there, he said yes: “I was introduced as the messenger for Sheik Osama bin Laden.”

Moussaoui says that prominent Saudis visited bin Laden’s camp in Afghanistan in return: “There was a lot of bragging about I been to Sheik Osama bin Laden, I been to Afghanistan, I’m the real deal, I’m a real mujahid, I’m a real fighter for Allah.”

He says that bin Laden’s mother visited too, testimony that has also led to attacks on his credibility since he says that Hamid Gul, chief of Pakistan’s Inter-Service Intelligence, helped arrange it even though Gul by that time had been out of office for a decade. But Gul is a powerful player in Pakistan’s murky politics to this day, so the notion that he would help organize a visit by bin Laden’s mother even though no longer head of the ISI is hardly farfetched.

The Guardian has also labeled as “improbable” Moussaoui’s tale of smuggling a Stinger missile into the U.S. under diplomatic immunity in order to shoot down Air Force One. But Moussaoui was careful to note that it was not a prince who suggested such an operation, but a comparatively lowly member of the Saudi Embassy’s Islamic Department in Washington.

Moreover, the proposal “was not to launch the attack, it was only to see [to] the feasibility of the attack.” If, as he says, the Wahhabi cleric Muhammad ibn al Uthaymeen did indeed issue a fatwa declaring that embassy personnel “had a personal obligation to help the jihad if they can, even if they were not order[ed] by … the Saudi government,” then it is hardly inconceivable that an individual Wahhabi militant might have decided to take matters into his own hands.

The Cover-Up

None of this means that Moussaoui’s charges are true, merely that they’re plausible and therefore merit further investigation. But what makes them even more persuasive is the behavior of those in a position to know, not only the Saudis but the Americans as well.

Since virtually the moment the Twin Towers fell, top officials have behaved in a way that would tax the imagination of even the most fevered conspiratorialist. Two days after 9/11, Bin Sultan, the Saudi ambassador at the time, met with Bush, Dick Cheney, and National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, after which 144 Saudi nationals, including two dozen members of the Bin Laden family, were allowed to fly out of the country with at most cursory questioning by the FBI.

The Bush administration dragged its feet in the face of two official investigations, a joint congressional inquiry that began in February 2002 and an independent commission under Thomas Kean and Lee H. Hamilton the following November. When Abdullah visited Bush at his Texas ranch in April 2002, the question of 9/11 hardly came up.

When a reporter pointed out that 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudis, Bush cut him short, saying, “Yes, I – the crown prince has been very strong in condemning those who committed the murder of U.S. citizens. We’re constantly working with him and his government on intelligence sharing and cutting off money … the government has been acting, and I appreciate that very much.”

Yet just a month earlier, former FBI assistant director Robert Kallstrom had said of the Saudis, “It doesn’t look like they’re doing much, and frankly it’s nothing new.” In April 2003, Philip Zelikow, the independent commission’s neocon executive director, fired an investigator, Dana Leseman, when she proved too vigorous in probing the Saudi connection. [See Philip Shenon, The Commission: The Uncensored History of the 9/11 Investigation (New York: Twelve, 2008), pp. 110-13]

Strangest of all is the famous 28-page chapter from the 2002 joint congressional report dealing with the question of Saudi complicity. While the congressional report was heavily redacted, the chapter itself was suppressed in its entirety. Obama promised 9/11 widow Kristen Breitweiser shortly after taking office that he would see to it that the section was de-classified, yet nothing has been done.

Why did Obama go back on his word? Is it the text itself that’s so explosive? Or do the Saudis have something on the U.S., something very damaging, that they are threatening to release if it tries to blame them for 9/11? All we can do is speculate.

The Great Unraveling

The U.S. and Saudi Arabia are a pair of odd fellows if ever there was one. One is a liberal republic in the classic Nineteenth Century definition of the term while the other is perhaps the most illiberal society on the face of the earth. One is officially secular while the other is an absolute theocracy.

One professes to believe in diversity while the other imposes a suffocating uniformity, banning all religions other than Wahhabist Islam, forbidding “atheist thought in any form,” and prohibiting participation in any conference, seminar, or other gathering, at home or abroad, that might have the effect of “sowing discord.” One claims to oppose terrorism while the other “constitute[s] the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide,” according to no less an authority than Hillary Clinton.

The alliance has served the imperial agenda but at appalling cost. This includes not only 9/11 and ISIS, which Joe Biden said the Saudis and others Arab gulf states funded to the tune of “hundreds of millions of dollars,” but the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris as well, which was financed by Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, a group that, according to former U.S. Ambassador to Morocco Marc Ginsberg, has also benefited from Saudi Arabia and other Arab gulf largesse.

This is the dark side of the alliance that Washington has struggled to keep under wraps. But Moussaoui’s testimony is an indication that it may not be able to do so for much longer.

Daniel Lazare is the author of several books including The Frozen Republic: How the Constitution Is Paralyzing Democracy (Harcourt Brace).

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten