BOOKS & THE ARTS / SEPTEMBER 5, 2023

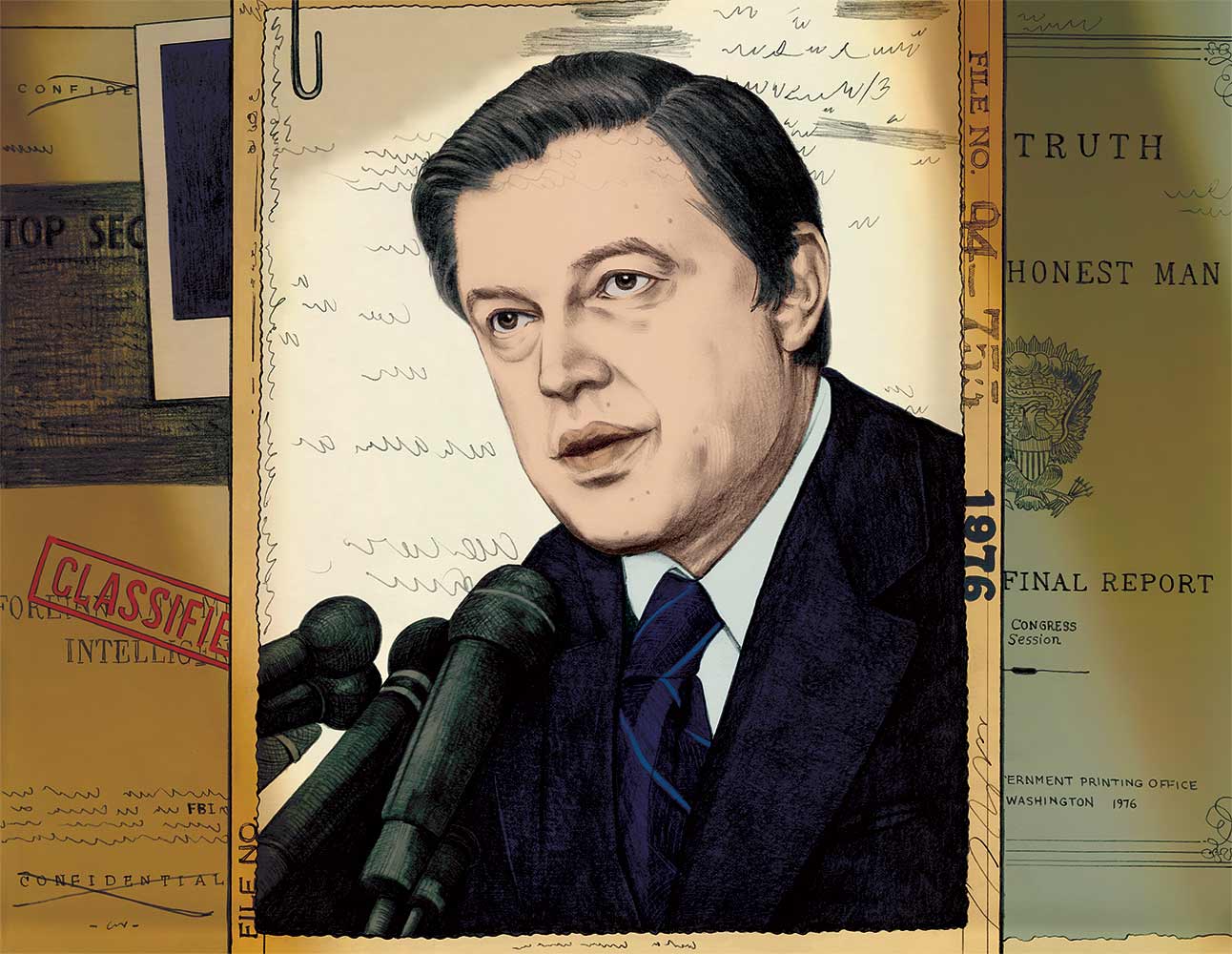

The Senator Who Took On the CIA

Frank Church and the committee that investigated the US intelligence agencies.

On November 3, 1791, in what today is western Ohio, some 1,400 US soldiers under Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair, accompanied by more than 100 wives, children, prostitutes, and other camp followers, stopped for the night on the banks of the Wabash River. The inept St. Clair failed to order his men to prepare any breastworks or defenses. The next morning, as they were cooking breakfast over their campfires, the troops were overwhelmed by a well-planned attack by roughly 1,000 Native Americans angry about the tide of newcomers invading their lands. Discipline collapsed, and only a few hundred soldiers managed to break out and flee. The battle left 657 troops dead and 271 wounded. It would be the greatest military defeat that Native Americans ever inflicted on the US Army.

Books in review

The defeat shocked the infant republic, and early the next year the House of Representatives set up a select committee to investigate. The seven-member panel began to hold public hearings, paying witnesses $1 a day. The politically well-connected St. Clair attended most of the sessions, and his presence—and perhaps some unrecorded lobbying by him and his supporters—seems to have intimidated the committee into exonerating him: After a month, it issued a report declaring that St. Clair had “discharged the various duties which devolved upon him with ability, activity, and zeal.” The select committee blamed the disaster, unconvincingly, on the quartermaster and contractors, who had allegedly supplied the troops with faulty gunpowder, saddles, axes, and shoes.

In its timidity about holding the powerful to account, this first congressional investigation was typical of far too many to come. No such failure was made, however, by the most recent significant investigation, also by a select committee of the House, into the January 6, 2021, attack on the US Capitol. Its riveting hearings and brilliantly edited video were enough to make even the most jaded radical feel that there’s something worthwhile in our Constitution after all.

The 230 years between these two sets of hearings have seen hundreds of other congressional investigations, but arguably the most significant of them all was that of the Church Committee, as it came to be known, from 1975 to 1976. Chaired by Frank Church, a Democratic senator from Idaho, the committee’s several months of hearings and voluminous written report exposed an astounding variety of misdeeds by US intelligence agencies. The FBI, the committee found, had directed a massive campaign of surveillance, harassment, and attempted blackmail against Martin Luther King Jr. It had infiltrated activist groups and monitored the legitimate political activities of thousands of Americans. The CIA had plotted to assassinate—both successfully and unsuccessfully—a variety of leaders in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. It had enlisted the Mafia in its attempts to kill Fidel Castro and had tested large doses of LSD on unwitting subjects. It is hard to recall any other moment in American history when so much horrifying skulduggery was revealed.

The Church Committee, and Church himself, is the subject of a new book by the veteran correspondent James Risen, collaborating with his son Thomas, an aviation and business journalist. James Risen is one of our finest investigative reporters: His long and dogged pursuit of intelligence-agency overreach spanning several decades has led him to clashes with his former longtime employer, The New York Times. In addition to his books, he now writes mostly for The Intercept. What is notable about the Risens’ new volume, however, is that the revelations it explores were made not by journalists but by legislators.

Frank Church was born in Boise, Idaho, to a Catholic family; his father was the owner of a sporting goods store. Politically ambitious since childhood, Church served as an Army intelligence officer in China during World War II—a useful thing to have on your résumé if you were planning a run for office. He got a head start in Idaho politics by marrying Bethine Clark, whose father and uncle had both served as governor. Church was elected to the US Senate in 1956 at the age of 32, a bare two years above the constitutional minimum of 30. No matter how striking that early success, Church seemed an unlikely person to ever lead a pathbreaking investigation into US national security abuses. His was a rural, increasingly conservative state with a large Mormon population and more sheep than people, and Church correctly predicted that he would be “the last Democrat elected to the Senate from Idaho.” Furthermore, for most of his first decade in Washington, he was a conventional cold warrior, voting for the notorious Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, the legal underpinning of President Lyndon Johnson’s fateful escalation of the Vietnam War.

But as Church’s son wrote later, his father “regretted that vote to the end of his life.” Almost as soon as he cast it, Church began to develop doubts, not just about Vietnam but about the wider arrogance of a United States that was trying to shape events on the other side of the Pacific. Later he would compare it to the Soviet Union’s ruthless suppression of the Prague Spring in 1968. He was, as the Risens put it, “radicalized by Vietnam,” although some would dispute their claim that Church “did more than any other member of Congress to rein in Nixon’s war and bring about peace.”

Church’s break from the mainstream over the Vietnam War opened his mind in other ways as well. Soon he became concerned about the power that private companies wielded over US foreign policy, and in 1972 he managed to get himself appointed chair of the new Senate Subcommittee on Multinational Corporations. He led the first congressional investigation into an issue that remains central today: the American oil industry’s close ties to Saudi Arabia. His subcommittee’s hearings revealed one scandal after another involving big business buying favors from the US or foreign governments. Among the culprits were ITT, Northrop, and, above all, Lockheed, which had bribed officials in half a dozen countries to purchase its high-priced airplanes. The Risens relate a telling moment when Church, grilling Lockheed chairman Dan Haughton, asked him, “What’s the difference between a bribe and a kickback?”

Haughton argued that a kickback is “something in the price that you return to the buyer. A bribe is where you ask for a service…though I’m no authority….”

“If you aren’t an authority,” Church replied acidly, “I don’t know who is.”

Church’s fellow senators became alarmed that he was going too far. Two of them, Democrat Hubert Humphrey and Republican Jacob Javits, resigned from the subcommittee and then orchestrated its abolition and replacement by a tamer one on foreign economic policy.

Meanwhile, the Watergate scandal had produced a chain of revelations. At the end of 1974, the journalist Seymour Hersh had published a massive New York Times story detailing illegal CIA spying on at least 10,000 American citizens during the Vietnam War. Senate majority leader Mike Mansfield had long fretted about the lack of congressional oversight of the CIA, and the exposé gave him the chance to finally act, forming a select investigative committee in early 1975.

Church lobbied successfully to become its chair. He faced plenty of obstacles: Dick Cheney, then the deputy White House chief of staff, and Henry Kissinger, the secretary of state and national security adviser, aggressively tried to stonewall his every move. President Gerald Ford at times overrode Cheney, but he also tried to distract attention from Church’s inquiry by appointing his own investigative commission, led by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller.

Once the Church Committee’s investigation was mostly complete, the White House tried to discredit it in a particularly nasty way. In December 1975, Richard Welch, the CIA station chief in Athens, was assassinated by Greek left-wing guerrillas angry at the United States for its role in installing a military junta in their country. Through whispers to friendly reporters and members of Congress, the Ford administration blamed Welch’s death on the Church investigation. The charge was nonsense; Welch’s identity as the CIA station chief was no secret and had even been mentioned in the Greek press. But the administration’s attempt to tar Church was skillfully managed: The aircraft bringing Welch’s body home circled Andrews Air Force Base for 45 minutes so it could land at just the right moment to be filmed for the morning TV news programs. Although no president had ever before gone to the funeral of a CIA officer, Ford—along with Kissinger and other top officials—attended the service for Welch.

It is hardly surprising that the White House wanted to discredit the Church Committee, for its revelations were perhaps the most embarrassing blow that Congress has ever inflicted on the executive branch. Most shocking were the committee’s disclosures of the CIA’s attempts to assassinate foreign leaders. Not only had the agency tried to kill Castro in Cuba, but it had plotted to murder the democratically elected Patrice Lumumba in Congo. (Its assassins bungled the job, but the Belgians and Congolese, assuming they had the CIA’s blessing, carried it out.) The agency had also supplied weapons to the plotters who killed Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo in 1961, and it supported the coup that deposed and killed South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem two years later. In 1970, the CIA supported the right-wing officers who shot and killed Gen. René Schneider, the commander in chief of the Chilean Army and a man who staunchly opposed proposals for the coup d’état that would eventually overthrow and kill the elected left-wing president, Salvador Allende.

The Church Committee’s discoveries led to other revelations. The disclosures about the vast amount of surveillance that the FBI and the CIA had performed on activists during the Vietnam War prompted many radicals to use the Freedom of Information Act to retrieve endless pages of such records about themselves, albeit with the names of informants blotted out. Others have used the act over the years to help pry out of a reluctant FBI ever more information about its obsession with Martin Luther King Jr. The Last Honest Man reminds us of some lesser-known details as well: For example, not only was the FBI intent on getting rid of King, preferably by suicide, but it had a replacement for him in mind as the presumptive leader of Black Americans. This was to be the Republican lawyer Samuel Pierce, who would later serve as Ronald Reagan’s secretary of housing and urban development.

Operating with a bipartisanship unimaginable today, the Church Committee fought back against both White House and CIA attempts to block the release of its findings. It issued a multivolume final report in 1976. Church made a short-lived run for the Democratic presidential nomination that same year, but former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter had it sewn up. The senator’s moment of glory was over, but he at least had the satisfaction of seeing Congress pass the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act in 1978, which for the first time imposed some limits on the government’s ability to spy on American citizens. In 1980, Church lost his bid for reelection to the Senate. He died of cancer only a few years later, at the age of 59.

“What is left is the core truth,” the Risens write. “Frank Church and his committee took on the CIA, the FBI, and the NSA, and succeeded in bringing them under the rule of law for the first time.” Yes, but as the authors know better than anyone, these agencies haven’t always followed the law. Just how far they often stray has been shown by Edward Snowden’s brave whistleblowing, which revealed how the National Security Agency was tracing the phone calls and text messages of millions of Americans. It has also been demonstrated by Jeffrey Sterling in revealing (to James Risen, in fact) a badly bungled CIA attempt to supply faulty blueprints of nuclear warheads to Iran. And, of course, there was the unconscionable order by the George W. Bush–Dick Cheney administration for the CIA to use torture on its prisoners. Vast power always carries the possibility of vast abuse, and without vigilant oversight, that risk will remain.

Today, however, an enormous danger looms somewhere else entirely. Far greater than the information gathering carried out by the government is the surveillance done by private corporations. Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Twitter (or X, as it has since been rebranded under Elon Musk) know more about our actions, beliefs, loves, hates, and friend networks than even the most determined FBI agents of a half-century ago as they opened our mail or listened in on our phone calls. So far, that knowledge has mostly been put to work selling our attention to advertisers. But we have already seen how Facebook’s algorithm feeds material to its users that reinforces their beliefs, no matter how prejudiced or conspiratorial. And Musk provided Ron DeSantis with a platform for his presidential campaign kickoff and has repeatedly used Twitter to block opinions he doesn’t like and voices that a variety of governments want silenced. The ominous political potential of these vast corporations combining their powers of censorship with what they know about us from our billions of clicks and keystrokes can barely be imagined.

Even half a century ago, before all this was in sight, Frank Church seemed to sense the danger ahead. As he warned in 1975:

The United States government has perfected a technological capability that enables us to monitor the messages that go through the air…. That capability at any time could be turned around on the American people and no American would have any privacy left, such is the capability to monitor everything…. There would be no place to hide…. I don’t want to see this country ever go across the bridge.

Unfortunately, we have indeed already crossed it, and we will need more than another Church Committee to find our way back

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten