Does Ukraine really have a neo-Nazi problem?

JVL Introduction

Larry Cohler-Esses writes that:

“In its existential struggle against Russian invaders, Ukraine, a pro-Western democracy, has elevated some problematic heroes with fascist origins. And its allies — including Jewish leaders and liberal politicians usually on guard against such forces — have largely downplayed or denied this phenomenon.”

His article provides a thoughtful analysis of the significance of this Nazi and antisemitic influence in Ukraine and of views as to how Jewish commentators and organisations who focus on antisemitism variously ignore, condone or condemn it.

Cohler-Esses does not extend his analysis to compare how significant neo-Nazi and anti-Jewish sentiment in Ukraine is often tolerated while the comments of those supporting Palestinian rights are picked over syllable by syllable to discover, or generate, hints of possible antisemitism.

RK/MC

This article was originally published by Forward on Fri 28 Jul 2023. Read the original here.

Does Ukraine really have a neo-Nazi problem? US officials won’t say

Some Jewish leaders have pulled back their criticism of the Azov Brigade since Russia’s invasion

It’s hard to know if Paul Massaro was oblivious or indifferent to the Nazi origin of the banner he proudly brandished.

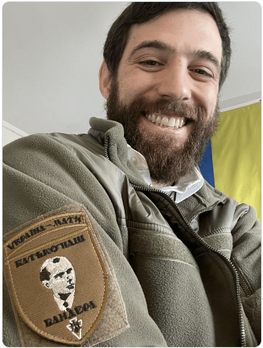

The flag, sent to him by the Ukraine Army’s Azov Brigade, featured a near-facsimile of the so-called wolfsangel symbol used by the Nazi Waffen SS. It is the unit’s official insignia. But when critics called him out for the selfie he posted on Twitter in February, Massaro — a senior official on a congressional commission that promotes human rights and democracy — was unapologetic.

Instead, he lauded the “heroic last stand” that Azov had made against Russia in last year’s siege of Mariupol, and celebrated the Ukrainian government’s decision to formally elevate it to brigade status as new recruits swelled its ranks.

Six days later, Massaro posted a beaming photo of himself with an arm patch honoring Stepan Bandera, a World War II-era Ukrainian nationalist whose forces killed tens of thousands of Jews and Poles in multiple pogroms. “Hey, look what I’ve got,” he wrote above the picture.

Critics erupted — but Massaro dug in. He noted that Ukrainians view Bandera, who collaborated with Nazis in his yearslong struggle against the Soviet Union, “through the lens of the struggle for Ukrainian independence.”

Massaro eventually deleted both posts. But his tweets and the responses exemplify a discomfiting trend: Nearly 18 months into Russia’s war on Ukraine, the West’s tolerance of far-right actors has reached levels not seen since the 1930s.

Enemy of the enemy

In its existential struggle against Russian invaders, Ukraine, a pro-Western democracy, has elevated some problematic heroes with fascist origins. And its allies — including Jewish leaders and liberal politicians usually on guard against such forces — have largely downplayed or denied this phenomenon.

At least 13 members of Congress, for example, have met with Azov Brigade members and their spouses over the last nine months, despite Congress having banned U.S. funding for the unit since 2018 because of its extremist roots. In June, an Azov delegation met with a leader of Human Rights Watch — a watchdog group that in 2015 reported“numerous allegations of unlawful detention and the use of torture” by the unit.

Azov members have also been welcomed twice at Stanford University, where they were lauded by former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul and the noted political scientist Francis Fukuyama, who later told the news website SFGate that he viewed them as “heroes.”

And the Anti-Defamation League, the world’s premier antisemitism watchdog, has softened its assessment of the group since Russia’s invasion.

Advocates and academics disagree on how much the Azov Brigade and its offshoots have evolved from the group’s extremist roots. But even some of the unit’s critics worry that a clash over the group may lend credence to Russian President Putin’s false narrative that Ukraine itself is a Nazi state and its army a fascist force.

“I think we need to speak out,” said Abe Foxman, a former leader of the ADL, “but make sure it doesn’t undermine the nation that is struggling for our system.”

Troubling roots, changing narratives

Stepan Bandera, circa 1934. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Bandera, who was on Massaro’s armband, is lauded by many Ukrainians for leading a long armed struggle for Ukrainian independence against Poland and the Soviet Union beginning in the 1930s, through World War II, and even afterward.

There are streets named after him and monuments to him in public squares; a Bandera bust graces the office of Ukraine’s military chief. The failure of Bandera, who envisioned Ukraine as an ethnically pure, fascist state, to halt or even condemn the pogroms in which his forces killed an estimated 38,000 Jews and at least 70,000 Poles is mostly denied or evaded by his countrymen.

(The U.S. Army also protected him from Soviet demands for his extradition as the Cold War loomed, considering him “too valuable an asset,” according to historian Thomas Boghardtof the U.S. Army Center of Military History.)

The Azov Brigade was established by far-right Ukrainian nationalists in 2014 in response to Russia’s invasion of Crimea. It started as a volunteer civil militia founded by Andriy Biletsky — a neo-Nazi who wrote in a 2010 manifesto that Ukraine’s mission was “to lead the White Peoples of the world in the last crusade for their existence; a crusade against the sub-humanity led by the Semites.”

Biletsky, who is now 44, left Azov in 2016, when he was elected to Parliament, where he served until 2019. He now leads a right-wing political movement called the Azov Movement, which has its own paramilitary force, known as the National Militia, with an estimated 20,000 volunteers.

Many of the Azov Brigade’s current senior commanders come from Biletsky’s original group and remain tied to him politically. But the brigade’s spokespeople have told news outlets that its fascist roots have withered.

They say the unit’s flag insignia — bearing the appearance of a tilted uppercase ‘N’ with an uppercase ‘I’ slashing through it — is not modeled on the Waffen SS wolfsangel, which remains popular with neo-Nazis today; it stands instead for the National Idea — meaning Ukrainian nationalism — though Ukraine uses a cyrillic alphabet, which does not include the letter ‘N.’

(In 2015, the unit dropped from its logo’s background a black sun symbol known as the sonnenrad that was also used by the Nazis.)

Today, the brigade itself has an estimated 2,500 active soldiers, with affiliated units that, taken together, have about 5,000.

This is a tiny fraction of Ukraine’s 1.3 million active fighters, reservists, and police and paramilitary forces. But Azov’s ferocity in battle has won it fame and recognition far beyond its numbers. During the three-month siege in the eastern city of Mariupol, dubbed “A New Masada” by The Wall Street Journal, they were the main fighters who dug in at an abandoned steel mill with little food or water. Several hundred were taken prisoners of war.

“This is their political strategy — to be the best fighting force they can and to get the populace to associate them with military heroism,” said Daniel Trombly, a doctoral candidate at the George Washington University researching radical movements and paramilitarism. “It’s done quite a lot for their reputation, even if people like them despite their ideology instead of because of it.”

But Andreas Umland, a Kyiv-based analyst with the Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies, said it’s not a political strategy at all.

“They’re not an ideological phenomenon anymore,” he argued, noting that Azov is now fighting under the general military command and has many new recruits who are not from Biletsky’s core group.

An argument over priorities

Two of the leading U.S. groups fighting antisemitism — the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the ADL — are also at loggerheads in their views of the Azov Brigade and the lionization of Bandera.

Efraim Zuroff, who coordinates Nazi war crimes research at the Wiesenthal Center, criticized Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy for failing to call out the brigade’s continued use of a Nazi-inspired insignia and ongoing ties to right-wing radicals.

“I can appreciate that he wants to keep these men fighting — they’re good fighters,” Zuroff said. “But you must put your foot down. If you want to be a democracy, you don’t walk around with Nazi symbols.”

Embracing the Azov Brigade and Bandera “only feeds Putin’s lies that Ukraine is a Nazi country,” Zuroff added. “It’s not a Nazi country. It’s a country that glorifies murderous Nazi collaborators, though.”

That’s just the kind of narrative the ADL is determined to avoid.

“We need to keep priorities straight,” said Andrew Srulevitch, the group’s director for European affairs. “We are not going to contribute to Russian propaganda that is aimed at lowering American political support for Ukraine just because we see a few guys with worrying arm patches.”

The actual threat posed by Ukraine’s far right, he said, was “negligible.”

‘Far fewer’ extremists than in the past

The ADL’s assessment of Azov has undergone a profound shift since the start of the current war in Ukraine.

Back in 2019, the group described the Azov Battalion in a report as “a Ukrainian extremist group and militia” that “has ties to neo-Nazis in Ukraine” as well as white supremacists worldwide.

A week after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the ADL described Azov as “the Ukrainian national guard unit with explicit neo-Nazi ties.”

But by November, the ADL told a reporter for a pro-Russian news outlet called Grayzone that its Center on Extremism “does not see the Azov Regime as the far-right group it once was.”

Srulevitch said the Center on Extremism’s most recent assessment is that “it is impossible to say how many extremists might still remain within the Azov unit, but it would certainly be far fewer than it had in the past.”

The ADL’s equivocal stance goes beyond Azov. In a June New York Times article about some Ukrainian soldiers’ use of Nazi-derived symbols on their uniforms, an ADL spokesperson did not express outrage.

A Ukrainian soldier with a patch containing the Totenkopf symbol, which was posted by Ukrainian officials to Twitter but later deleted. Photo by Vlad Novak/Ukraine Ministry of Defense via Twitter

Instead, discussing one photo the article highlighted — a soldier with a skull and crossbones patch known as the Totenkopf, which was famously adopted by the Nazi SS — he said he could not “make an inference about the wearer.” The soldier’s specific Totenkopf, said the spokesperson, appeared to be merchandise of a British neo-folk band called Death in June.

The band’s name memorializes a June 1934 event known as “The Night of the Long Knives,” in which Hitler executed leaders of the Nazi party who helped bring him to power. Many of its songs contain Nazi references; a 1995 album was titled Rose Clouds of Holocaust.

When I asked Mark Pitcavage, a senior ADL researcher, about the band, he told me that its members deny that they have extremist leanings.

“Some comments from band members suggest they may have right-wing sympathies,” he said. “But we recognize that not all Death in June fans are white supremacists.”

Zooming out

Srulevitch, the ADL’s European affairs director, said that regardless of some Ukrainians’ use of Nazi symbols and admiration for the Azov Brigade and Bandera, he is not worried about the country being taken over by extremists or antisemites.

In the 2019 election that made Zelenskyy the country’s first Jewish president, he noted, Ukraine’s far-right bloc won about 2% of the vote. In the ADL’s 2023 global survey regarding Jew-hatred, 29% of Ukraine’s populationexpressed antisemitic attitudes — above the European average of 22% and Russia’s 26%, but below Poland’s 35%.

“So we know that in Ukrainian society far-right extremism is negligible,” Srulevitch said. “It’s fair to assume something similar in the military. Maybe it’s something more there. But it’s not a serious issue.”

Foxman, who ran the ADL for 27 years ending in 2015, called Srulevitch’s characterization “sophistry.”

“Twenty-nine percent is very serious — that’s almost one-third of the country,” he said. “The priority is to maintain Ukraine as a free country, but not to close our eyes to history, One should not negate the other.”

If some Jewish leaders are grappling openly with the tension between their support of Ukraine in the war and their concerns over the ideology of some of the soldiers fighting it, U.S. government officials seem to have adopted a strategy of silence.

No comment

I had hoped to talk about this to Ambassador Deborah E. Lipstadt, the Holocaust historian who President Joe Biden appointed last summer as special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism. Her office invited me to submit questions via email, which I did on June 14, but then failed to respond despite multiple follow-up emails and phone calls.

A spokesperson for the Helsinki Commission, the congressional human rights watchdog that employs Massaro — the man who posted selfies with the Azov flag and Bandera armband — did not return multiple phone messages.

Sue Walitsky, a spokesperson for the Democratic co-chair of the commission, Sen. Ben Cardin of Maryland, said that Massaro, a senior policy adviser, “has been spoken to about the inappropriate nature of his posts” and “removed the tweet with the arm patch after one such discussion.”

Massaro declined to speak on the record, citing restrictions on public statements by Helsinki staffers. On Twitter, Massaro said he had decided to delete the Bandera post “at the request of a good Polish friend.”

Senator Cardin, in response to a query about Azov and Bandera, issued a generic statement saying: “The glorification and promotion of symbols related to Nazism are always wrong, divisive and must be denounced.”

Cardin’s Republican co-chair, Rep. Joe Wilson of South Carolina — one of the House members who met last monthwith the Azov delegation — did not respond to multiple emails.

‘It will never be 100% about human rights’

Several prominent public intellectuals marshaling support for Ukraine also declined my requests to discuss this issue, including McFaul, the former ambassador who now runs an international studies program at Stanford.

One who did respond was Leon Wieseltier, who co-convened a 2014 conference of writers in Kyiv to “curse Putin in six or seven languages,” as he put it.

“We’ve been here before,” Wieseltier said. “When American Jews supported anti-Communist movements in Eastern Europe, we knew full well that the people for whose freedom we were advocating had very nasty records.

“We did that for philosophical and practical reasons,” he continued. “Because Jews who believe in freedom believe in universal freedom, those who believe in democracy believe in universal democracy.”

Wieseltier noted that in 1940s Poland, “Ukrainians murdered my own family members.”

“I believe antisemitism should be condemned loudly and immediately wherever it appears,” he said. “I don’t believe in thinking pragmatically about that.”

Wieseltier said that Lipstadt, in particular, should be speaking out, noting that “she was hired to condemn antisemitism.”

But Ira Forman, President Barack Obama’s antisemitism envoy, said it’s not always that simple. “I’m a big human rights advocate, but it will never be 100% about human rights,” he told me in an interview.

Working under the multiple, sometimes conflicting priorities that characterize any administration, Forman found himself asking, “What are the most winnable and most important fights?”

He said one key criterion was the danger posed to Jews in the country. And he had found that Ukraine’s Jews didn’t see the country’s ultra-right as the ones committing most incidents of antisemitism; instead they believed it came from Russians or Russian sympathizers trying to pin a fascist label on the Ukrainian government.

Neo-Nazis who don’t mind Jews

Indeed, several experts who follow Ukraine’s ultra-nationalist right closely told me something I found surprising: Their activists generally do not target Jews.

“All the specialists I consult say that there is no evidence of antisemitism among Ukrainian neo-Nazis,” said David Fishman, a professor of Jewish history at the Jewish Theological Seminary who visits the region frequently.

“It’s kind of a youth culture,” he explained. “It stresses aggression, hatred and violence. That’s what the Nazi symbols mean to them. But who are the objects of all that? This is flexible, pliable and has metamorphosed.”

The top targets today, he said, are Russians, including ethnic Russians inside Ukraine whose national loyalty may be in question. After that come Africans and Roma.

Still, the popularity of Ukraine’s cause and the Azov Brigade’s own formidable PR operations are bringing the unit’s foreboding, Nazi-evoking symbols into the mainstream under a new, flattering spotlight.

The unit’s version of the wolfsangel insignia, for example, was projected on a screen behind McFaul, the former U.S. envoy to Moscow, when he welcomed members of the Azov Brigade to Stanford University in September.

A few weeks later in New Jersey, Ukrainian American children at a social gathering stared admiringly up at a visiting Azov delegation member, his yellow arm patch with the unsettling symbol on prominent display.

And in November, the Azov Brigade’s talented press director, Dmytro Kozatsky, appeared on Andrea Mitchell’s MSNBC show alongside Ukraine’s ambassador to Washington and Carol Guzy, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer. The network showed Kozatsky’s stunning photos from inside the Azovstal Steel Plant in Mariupol during Russia’s siege, as well as Guzy’s from wartime Kyiv.

“I wanted to take this picture as a symbol of this victory of good over evil,” Kozatsky told Mitchell, referring to an image of a thin beam of sunlight illuminating an Azov fighter inside the darkened plant, now gracing the cover of Guzy’s new Ukraine photo collection.

Mitchell made no mention of the photos on Kozatsky’s Twitter feed: of him in a T-shirt bearing the insignia of a notorious Waffen SS unit in May 2018; of a lasagna he baked with a swastika etched into it in March 2020, or of him wearing a shirt emblazoned with the code numbers 1488, which is listed in the ADL’s catalog of white supremacist hate symbols.

Nor did she ask Kozatsky why he had “liked” a tweetshowing Ukrainian graffiti saying “Death to Yids” with an SS symbol in March 2020.

These tweets were removed before Kozatasky’s MSNBC appearance, but remain archived. Eleven days later, a protester confronted Kozatsky about the tweets at the DOCNYC film festival in Manhattan, where he was promoting a documentary in which he stars that was made by an Israeli-American. After that protest went online, Kozatsky apologized on Twitter, describing his earlier tweets as “Ukrainian humor” meant as “a mockery of Russian propaganda about so-called ‘Nazism in Ukraine.’”

“In no way would I ever support, and do not support, the terrible actions of the Third Reich and Hitler,” he wrote. “Especially when nowadays we are fighting the direct successor of Nazism in the world — the Russian Federation.”

During our discussion, Srulevitch, the ADL official who downplays the far-right threat in Ukraine, made a stirring prediction: This war, terrible as it is, will transform the frightening phenomenon of Ukrainians adulating Bandera, ethnic mass murders and all.

Ukraine “now has many heroes who fought Russia but didn’t kill Jews — President Zelenskyy first and foremost,” he said. “Bandera will be supplanted by the heroes of this war.”

Perhaps. But whether those heroes should all be acclaimed as champions of democracy — in Ukraine and in the United States — remains a subject of significant debate.

Larry Cohler-Esses is an award-winning journalist. He has previously served as the Forward’s assistant managing editor and news editor, Editor-at-Large for the Jewish Week, an investigative reporter for the New York Daily News, and as a staff writer for the Jewish Week as well as the Washington Jewish Week. Larry has written extensively on the Arab-Jewish relations both in the United States and the Middle East. His articles have won awards from the Society for Professional Journalists, the Religious Newswriters Association, the New York Press Association and the Rockower Awards for Jewish Journalism, among others.

Further reading

Glyn Secker in Counterfire, June 2022: Neo-fascism, Nato and Russian imperialism: An overview of left perspectives on Ukraine – part 1 and Neo-fascism, Nato and Russian imperialism: An overview of left perspectives on Ukraine – part 2

Sergei Loznitsa and Maria Choustova in Haaretz, July 2023, ‘Dealing With Ukraine’s Past Collaboration With the Nazis Will Shape Its Future’. You can also view gthe article here. https://www.jewishvoiceforlabour.org.uk/article/does-ukraine-really-have-a-neo-nazi-problem/

1 opmerking:

Die Nazi-club was de perfecte asset om een burgeroorlog in gang te zetten.

Kennelijk heeft niemand het belang ingezien , om Oekraïne een neutrale positie in te laten nemen , en de macht van oligarchen tijdig in te dammen. Ik weet verder niks van de geschiedenis van Oekraine , maar Poetin is in in ieder geval wél in staat geweest de oligarchie in Rusland aan een leiband te leggen , na de Wild West jaren negentig.

Een reactie posten