Liberal Zionism is dying. Will foregoing the Jewish state save it?

A new book calls for Zionism to be re-envisioned as a binational project in order to shed Jewish historical trauma and salvage democratic values.

“Haifa Republic: A Democratic Future for Israel,” by Omri Boehm, New York Review Books, 2021.

In 1974, a small group of American Jewish leftists who considered themselves Zionists, named Breira, called for a two-state solution as a path to resolving to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The idea of a Palestinian state standing alongside a Jewish state was not unprecedented; nearly three decades earlier, it had been endorsed by the UN General Assembly through the 1947 Partition Plan. But at the time of Breira’s emergence, this position was viewed as so radical that, by 1976, the group was effectively crushed by the American Jewish establishment.

Shortly afterward, in 1978, the organization Peace Now was formed in Israel, offering liberal Zionists an ostensible movement toward a two-state solution. Like Breira, Peace Now was also considered out of the Israeli mainstream in its early years, and most liberal Zionists did not sign on. But by the 1980s, the two-state solution slowly made its way into the belly of the liberal Zionist base. By the end of that decade, it became its dogma, and by the 2000s, its raison d’etre.

Today, it is not provocative to say that the liberal Zionism espoused by groups like Breira and Peace Now is in a deep crisis. Not only has reality seemingly left the ideology behind, but the ideology itself has not really offered any new ideas in 30 years. The two-state solution is effectively dead, yet to abandon it is to cut out the very core of liberal Zionist identity — much like Chabad coming to terms with the fact that their beloved rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, is not the messiah. And so, the dogma continues because it must, because that is how dogma functions; it is impervious to “facts on the ground.”

All of this and more is addressed at length in Omri Boehm’s new book, “Haifa Republic: A Democratic Future for Israel.” Boehm argues that slogans such as “Jewish and democratic” and “two states” have become “empty clichés,” devolving the conversation around Israel into a shouting match between “chauvinistic Zionists” and the anti-Zionist left. For Boehm, liberal Zionists have largely been sidelined because the ideology they promote cannot square with the reality we see. For all their claims to liberal values, they are in fact defending an illiberal state, and cannot quite come to terms with that.

Boehm, an associate professor of philosophy at The New School for Social Research in New York, was raised in a small town in northern Israel that was established as part of a project to “Judaize the Galilee,” which he describes as “enable[ing] the government to confiscate the land of Arab Israelis [Palestinian citizens of Israel], check the natural growth of their villages, and disrupt territorial continuity between Arab Israeli towns.” A scholar of early modern continental philosophy (specifically Spinoza, Kant, and Decartes), Boehm, who considers himself a Zionist, has also written on Jewish topics and issues related to Israel-Palestine.

The purpose of “Haifa Republic” is to offer an alternative to a liberal Zionism that Boehm believes is moribund in large part because it cannot find a foothold in a world where the two-state solution has turned into a nostalgia for an idea whose time has passed. Yet Boehm suggests that liberal Zionism can still be salvaged if it abandons its two-state dogma and returns to its roots — not its post-1967 roots, but rather those before “statism” became the dominant vision for Jewish self-determination. In effect, he argues for a solution closer to what today would be considered a binational confederation, an idea that was not only popular among liberals before World War II, but at times tacitly supported even among reactionaries like Ze’ev Jabotinsky.

The original sin

In his book “My Promised Land,” Ari Shavit, who fashions himself a liberal Zionist, presents a “stark choice” that many of his ideological compatriots have neither quite absorbed nor admitted: “either reject Zionism because of Lydda (a city whose Palestinian citizens were expelled en masse and some executed in 1948), or accept Zionism along with Lydda.” Boehm takes this challenge seriously: Zionism, he argues, needs to be transformed or it can never survive in any liberal form. That is the spine of “Haifa Republic”: re-envisioning Zionism as a binational project which, he claims, was its original intent.

For Boehm, Israel as presently construed (and here he does not only mean as an occupying power) can never achieve liberal ends because it is no longer a liberal project, but an ethno-nationalist one. The “Jewishness” that Israel seeks to protect is not culture or religion, “but Jewish ethnicity, Jewish blood. That is what makes it a nationalist, but hardly a liberal project.” While the Palestinians living under military occupation after 1967 are categorized as “enemies,” Palestinian citizens inside the country’s pre-1967 borders are also constitutively “other;” they may be citizens of Israel, but as non-Jews, they are not the state’s priority.

The inherent incoherence of liberal Zionism, Boehm argues, is that it can only support an illiberal state (“accept Zionism along with Lydda”) and thus is constantly undermining or attenuating its liberal commitments. The ideology’s great fallacy is that 1967 represents the “original sin” behind Israel’s present reality, and that the occupation is its central existential problem. But Boehm shows that this is simply not the case. For example, he cites a Dec. 2, 1940 diary entry from Yosef Weitz, a high ranking official in the Jewish National Fund, which states:[1]

Among ourselves it must be clear that there is no room in the country for two peoples… if the Arabs leave it, the country will become wide and spacious for us… the only solution [after World War II ends] is a Land of Israel, at least a western Land of Israel, without Arabs. There is no room here for compromises.

Boehm also cites Moshe Sharett, Israel’s first foreign minister who, during a Jewish Agency meeting on May 7, 1944, openly spoke about transferring Palestinian Arabs from a future Jewish state, noting, “Transfer can be the crown jewel, the last stage of the political developments, but by no means the starting point.”[2] The Haganah’s secret “Plan Dalet,” which gave military officers the right to “cleanse, capture, or destroy” Palestinian villages at their discretion, is a key part of that legacy.

Israeli historian Benny Morris similarly made this clear decades later in an interview with Shavit for Haaretz in 2004: “Of course, Ben Gurion was a transferist,” Morris said, “without uprooting the Palestinians, a Jewish state would not have arisen here.” In another Haaretz interview with Adi Ofir, Morris compared Israel’s situation with the American genocide of Native Americans in the nineteenth century — hardly a standard commonly evoked in the 2000s, especially by those who experienced genocide themselves. Even with that comparison, Morris would come to defend these egregious policies as unfortunate but necessary evils for Israel’s creation.

None of these facts are new or contested anymore, and it is worth noting that Palestinian scholars and historians have been making these same arguments with documentarian evidence and testimony for decades, though are often summarily dismissed. Boehm nonetheless cites these sources to make a fundamental point about liberalism: that Israel’s real problem is not with 1967, but with the illiberal structure upon which the country was founded in 1948. As an aspiring “Jewish” state, Israel by nature requires the fewest number of non-Jews; others can live in the state, but on the condition that they do not negate, challenge, threaten, or even question its ethnic identity. This vision, he concludes, can never support a liberal project of any kind.

Boehm is by no means the only Jewish scholar to have understood this contradiction (and many Palestinian scholars, including citizens of Israel, have long arrived at this conclusion). His writing harkens back to Hannah Arendt’s reflections on the Atlantic City Conference held by the World Jewish Congress in 1944, which she called “a turning point in Zionist history.” One of the salient features of that conference, occurring in the midst of the genocide of Jews in Europe, was the unanimity of American Zionists in support of statehood. But Arendt responded, “[p]olitics dies when unanimity takes over — a unanimity that is intolerant toward dissent. The great danger to politics is a homogenization, a leveling out in which differences are not tolerated — where ‘loyal’ opposition is marginalized, suppressed, or violently repressed.”[3]

It was in Atlantic City, Arendt argued, where Israel’s maximalist project was codified: “the whole of Palestine, undivided and undiminished” became a central part of the Zionist mandate. The existence of a local Arab population was not even mentioned, as if reflexively adopting Israel Zangwill’s mythic “a people without a land for a land without a people.” The conference became the unspoken template of modern Israel: Palestinian Arabs existed only as part of the landscape or as individuals, but not as a viable collective in their own right.

‘Holocaust messianism’

A central question underlying Boehm’s study is: “what happened to liberal Zionism?” How did the liberal vision of Zionism as Jewish autonomy (and not necessarily sovereignty, a distinction to which I will return below) in a binational political structure turn into defending an illiberal ethnonational state? His answer is both obvious and ominous: the Holocaust. Boehm argues similarly to what Ian Lustik, in his book “Paradigm Lost,” calls “Holocaustia,” whereby the genocide serves as the template that justifies— and necessitates — the state’s ethno-nationalist outcome.

Readers will understandably be challenged by Boehm’s dissonant notion that unless Jews can “forget the Holocaust,” Israel can never embrace a liberal vision of self-determination. But by “forgetting,” Boehm does not mean to live as if the Holocaust never happened. Holocaust-centrism in Israeli society, as Boehm notes, was not immediate; during the 1950s, the genocide was hardly cited as a raison d’etre of Israel’s superstructure. Quite the opposite was true: Holocaust survivors were often viewed as the antithesis of Zionism, remnants of the powerless Jew that Zionism sought to replace.

Rather, Holocaust-centrism began in earnest with Israel’s trial of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in 1961. Here Boehm revisits, though doesn’t mention, one of the under-examined aspects of Arendt’s critique of the trial in her famous book “Eichmann in Jerusalem.” Arendt was not opposed to Eichmann being tried or even executed, but she was opposed to Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion creating a “show trial” as an exercise in collective catharsis to make the Holocaust a cornerstone of Israeli identity. Ben-Gurion was quite explicit about this political goal, even telling the Israeli daily Yedioth Ahronoth that “the fate of Eichmann the person has no interest for me at all. What is important is the spectacle.” One consequence of this “spectacle” was to ensure that “the Holocaust belonged to all Israelis” — that is, all Jewish Israelis — further communicating to Palestinian citizens that Israel was not their country.

What does it mean to “forget” the Holocaust? For this, Boehm uses the argument proposed by historian and Holocaust survivor Yehuda Elkana in a 1998 Haaretz essay entitled “In Praise of Forgetting.” Elkana argued that while memory is crucial to any collective identity, if it loses perspective, it also has the potential to paralyze a society’s progress. “Democracy’s very existence,” he wrote, “is endangered when the memory of past victims takes an active part in the democratic procedure.”

When genocide becomes the normative criteria for collective identity, Elkana continued, its constituents see the whole world as the enemy, even those who are their own citizens. At that moment, democracy becomes impossible. This worldview led Israeli politicians as disparate as Abba Eban and Yitzhak Shamir to assert that Israel’s borders are “the borders of Auschwitz.” The utter incoherence of such a claim — that a sovereign state with a modern military is comparable to disempowered masses rotting in a concentration camp — is not only grotesque but a sign of deep collective failure.

Boehm compares Elkana’s thesis with the contradictory work of the renowned writer and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel. A masterful and prophetic voice against hate and injustice worldwide, Wiesel simply could not evoke that voice when it came to Israel and its policies toward Palestinians. He could not do so, Boehm argues, because he could not get past “Holocaust messianism,” the theologization of Holocaust memory. Wiesel, for example, never questioned the long-term implications of policies such as Holocaust education in Israeli kindergartens, which New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman quipped would turn Israel into a “Yad Vashem with an air force.” For Wiesel, the Jews simply became the exception. The world needs to be just; the Jews need to survive.

Boehm does not single out the Jews for needing historical rethinking. The Palestinian Arabs, he argues, also have soul-searching to do and must similarly learn to acknowledge and “remember to forget” the Nakba. Their own attachment to victimhood, he writes, disables them from joining a liberal project that would affirm their identity in a land for two peoples. One way of doing this is to acknowledge the Holocaust on its own terms. Here Boehm cites Joint List parliamentarian Ahmad Tibi, the first Arab to give a formal address at Israel’s official Holocaust Memorial Day commemoration in 2010, who spoke passionately about the depravity and trauma of the genocide without mentioning the catastrophe that befell Palestinians. Israeli Jewish leaders, Boehm suggests, should also passionately affirm the Nakba without needing to mention the Holocaust.

Presently, this idea is almost a utopian fantasy. For much of Israel’s history, and particularly under the reign of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel has been locked into a Holocaust messianism that can only result in ethnonational chauvinism, making Israelis feel that they are always one step away from another genocide. A truly liberal state could never emerge from such anxiety and paranoia.

Arendt recognized this when she opposed Jewish statehood in 1948, and argued that Palestine should go into international receivership for a decade in order to allow the Jews to begin rebuilding their lives in the aftermath of Nazism.[4] She knew then that the power of statehood in the midst of such trauma could never yield a healthy political collective. If Zionism is about the normalization of the Jews, the Holocaust is its opposite; there is nothing more abnormal than Auschwitz. Thus, if the Holocaust continues to drive Zionism, it undermines the entire project.

Mutual autonomy, shared sovereignty

So what does Boehm suggest? His binational one state is not a fantasy of fully integrated coexistence between Jews and Arabs from the river to the sea, like what we may find with earlier Zionist binationalists such as the members of Brit Shalom. Rather, it is a one-state confederacy of sorts with autonomous regions and one constitution that binds all its citizens together, equally protecting the rights of Jews and Arabs. In short, Boehm is asking Jewish Israelis to abandon exclusive “sovereignty” over the land of Israel in favor of equal Jewish and Palestinian “autonomy.” It is basically an alternative to Oslo’s two-statism, while accepting its basic premises that both peoples deserve self-determination throughout the land.

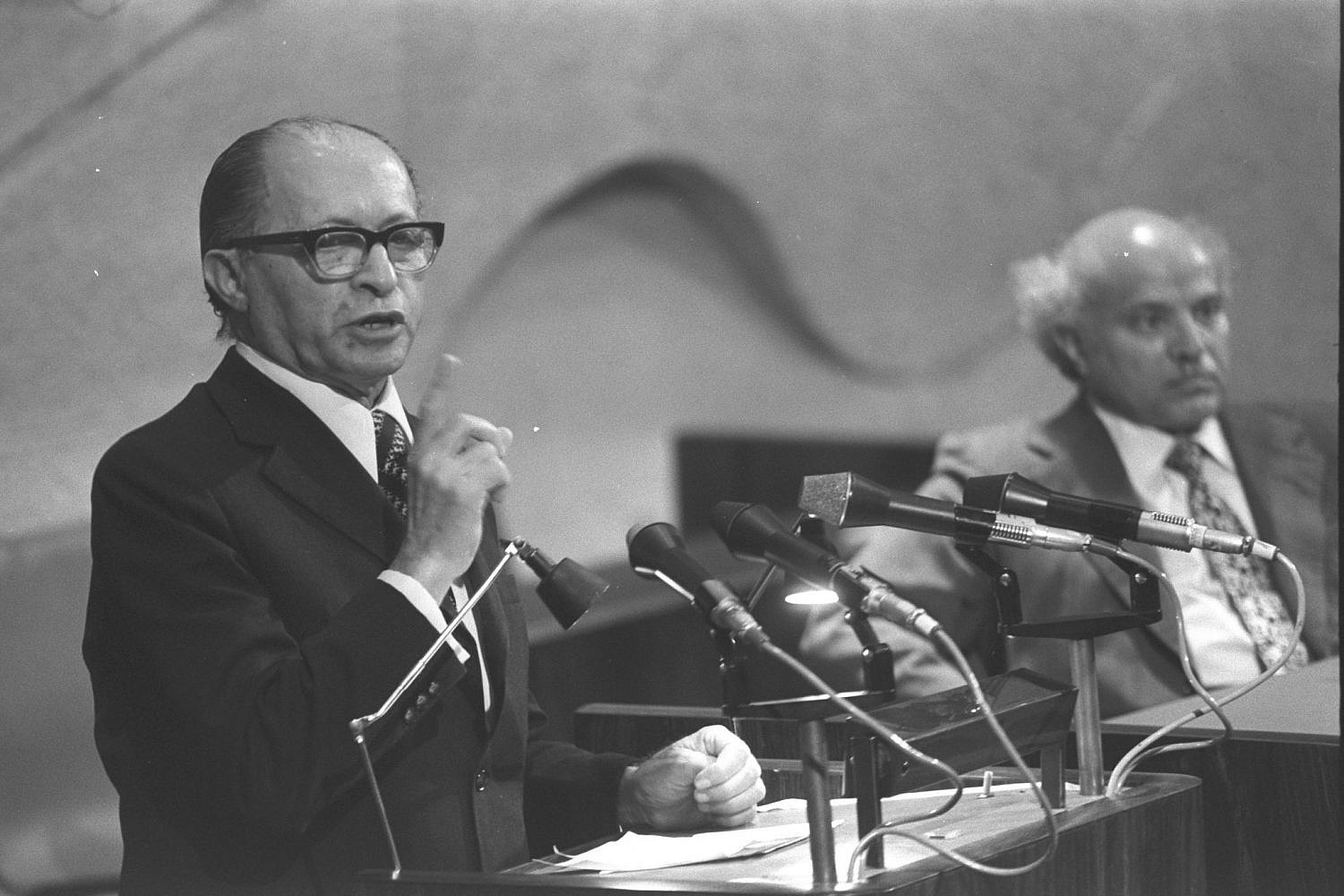

The distinction between autonomy and sovereignty is an important point for Boehm, who argues that many Zionists, from Jabotinsky to Ben-Gurion, at certain points envisioned the former and not necessarily the latter. Furthermore, he asserts, the idea of granting all Palestinians citizenship in one state is not only a view of the radical left, but also that of the Likudnik Prime Minister Menachem Begin, whose proposed “Autonomy Program” offered all Palestinians citizenship.

It is true that Begin’s plan was designed to better manage the occupation and not to end it, but Boehm sees in it the beginnings of a path to unraveling the bind that has led to Israeli apartheid. Through his expansive and revised view of Begin’s autonomy idea, Boehm argues that it “doesn’t just downgrade Palestinian sovereignty into self-determination; no, it also transforms the nature of sovereignty in Israel — expanding it beyond exclusive Jewish sovereignty. A state in which all Palestinians are offered full citizenship is one that has taken the main step towards becoming a republic for all its citizens.” Ironically, by implementing citizenship as a way out of the morass of occupation, Boehm is essentially using Begin against Begin’s own intentions.

Boehm doesn’t talk much about the occupation per se, and for good reason. From his perspective, the occupation is de facto over, calling it instead a form of “humane apartheid” — by which I assume he means that Israel has granted some autonomy to the Palestinians under its control, although autonomy on its own neither shifts the power dynamics nor removes the stigma of apartheid. Either way, for Boehm, this system can never square with any liberal vision of a nation-state. The point of his book is thus to look beyond the occupation toward a vision of a liberal democratic future that would level the power dynamic through shared sovereignty.

Boehm does not get mired in the gritty policy details of how this can be implemented on the ground; that is not his area of expertise, and in too many cases, the policy questions often serve as deflections of the intellectual stakes of Israel’s political future while defending the so-called “status quo.” For him, the key is for Israel to be willing to curtail some of its Jewish sovereignty by sharing it with the non-Jewish citizenry, which will enable both sides to maintain the autonomy they each desire in order to exercise their respective rights to self-determination. In other words, they should build a form of liberal democracy.

And why Haifa? Boehm claims that Israel too often is divided between Tel Aviv as the “Hebrew” city and Jerusalem as the “Jewish” city. Haifa, not often viewed as central to Israel’s identity, is for him the truly Arab-Jewish city — a symbol of what Israel should be. The Haifa port is where many European Jews disembarked, but also where many Palestinians fled for their lives in 1948. It is a symbol of entering and exiting, a transitory space where in practice, albeit not in principle, Israeliness did not completely erase Arabness.

Many Palestinians would question such a rosy view of coexistence in Haifa, past and present. But Boehm nonetheless sees in it a model for a binational future. As he writes, “Arab-Jewish politics is the only model for a democratic future in Israel — and the only model that propels a country beyond the two-state solution.” Many would call this vision post- or even anti-Zionist. Yet Boehm argues that such an alternative is in fact buried deep in the attic of liberal Zionism and is needed to save the ideology from collapse.

While I share Boehm’s vision, I am not quite convinced we need to call it Zionism at all. First, many of the Zionist figures Boehm cites to support his thesis, from Jabotinsky to Ben-Gurion to Begin, said and did many things that fundamentally undermine his vision. Boehm therefore becomes very open to the accusation of cherry-picking quotes to make a case that his sources never would have made, and in fact actively worked against. Liberal Zionism is a multivalent ideology, but it is not clear to me why the term, in all its complexity, needs to survive.

Second, and more importantly, missing in Boehm’s analysis is the deep impact of Religious Zionism, or Kookism (named after Rabbi Avraham Kook and his son Zvi Yehuda Kook), on Israeli society. This includes the impact it has had among many secularists who supported the settler movement in the occupied territories, helped to created Israel’s facts on the ground there, and joined in the pursuit of their maximalist vision. Furthermore, while “Jewishness” is discussed at some length, the book does not address the question of Judaism itself as an engine that reifies Holocaust messianism and serves as a tool of ideological and theological chauvinism, among religious and secular Israelis alike, that would render a binational solution impossible.

Indeed, in thinking about transforming Israel beyond Holocaust messianism, we also need to determine how to sever it from religious messianism. One problem is that in some circles, religion has devolved into a support of survivalism, which in some ways undermines covenantal theology. There are many scriptural and rabbinic references to support such a chauvinistic reading of the faith, and there are also many references that contest it.

This returns us to the tension between the particular and the universal that has exercised biblical and Jewish thinking for millennia. The Holocaust has in some ways tipped the scales. One response to the genocide, which Israel has clearly pursued, is to give up on Judaism’s universal call and to instead support a narrow survivalist need — but this has significant hazards. When Jews think they are the sole arbiters of their own fate, covenantal theology is denuded or at least destabilized. In such a scenario, God can easily become irrelevant besides serving as a weapon to procure one’s survivalist agenda.

There are certainly many religious sources to counter that narrow philosophy, but the theological dangers are plain to see. Unless the role of religion is addressed and a program is offered to sever religious messianism from the political, the “Haifa Republic” will remain a dream. But it is still a dream worth considering in a post-two-state era. At the very least, it can provide a life-raft for the followers of a liberal Zionism now floating aimlessly off the coastal city.

[1] Weitz, My Diary and Letters to My Children, Diary Entry Dec. 2, 1940, page 181.

[2] Proceedings of the Board of the Jewish Agency, May 7, 1944.

[3] Cited in Richard Bernstein, “Hannah Arendt’s Zionism,” in Hannah Arendt in Jerusalem, 201.

[4] Arendt, “To Save the Jewish Homeland,” in Hannah Arendt: The Jewish Writings, 400, 401.

Shaul Magid is Professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College and Kogod Senior Research Fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America. His latest book is “Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical” with Princeton University Press.

https://www.972mag.com/haifa-republic-book-review-liberal-zionism/

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten