How a US defense secretary came to support the abolition of nuclear weapons

By William J. Perry, December 7, 2020

Many people have asked me how a former secretary of defense could support the abolition of nuclear weapons. This paper is a partial answer to that question, in the form of a personal history of how my thinking on nuclear weapons has evolved from Hiroshima to the present time.

When we reached the 75th anniversary of Hiroshima, I was inspired to think back to that fateful day and to my own reaction when I heard the news. Back then, I was relieved that the terrible war would finally end, and I was intensely curious about how this new bomb worked. But I was not thinking about what the long-term consequences of such a bomb might be. That would come later.

What I saw in Tokyo and Okinawa totally removed any view that I had of the glory of war and convinced me that humanity could not continue its practice of engulfing the world in war every generation. The devastation I witnessed in Tokyo had been done with thousands of airplanes and tens of thousands of bombs over a period of years; equivalent devastation could have been inflicted on Tokyo with one plane, one nuclear bomb, in one instant. Similarly, the deaths and destruction in the Battle of Okinawa had taken place over several months and required an American landing force equivalent to what was employed on D-Day in Europe, and the Okinawa fighting cost tens of thousands of American casualties. The Japanese forces in Okinawa could have been defeated with one nuclear bomb, in one instant.

Einstein said that with the advent of the nuclear bomb, everything has changed, save our way of thinking. But what I witnessed in Tokyo and Okinawa began to change my way of thinking. It led me to believe that we would have to completely reconsider the role of war, which had been with us since the beginning of history. As deadly as World War II was even without nuclear bombs, a war where Hiroshima-type bombs were widely used would be a far greater catastrophe. I concluded that the only reasonable goal of our nuclear weapons should be to deter the use of nuclear weapons.

Then in 1952, the US tested a thermonuclear bomb that unleashed a destructive force 1,000 times greater than the Hiroshima bomb. A few years later the Soviet Union tested one even more powerful. Subsequently both the United States and the Soviet Union began deploying hydrogen bombs in their nuclear arsenals, most of them with a destructive power of 10 to 100 times the Hiroshima bomb. Each of our countries soon had the capability not only to destroy the other, but to actually create an extinction event, comparable to when a large asteroid struck the earth 66 million years ago, leading to the extinction of most animal species then living, including all dinosaurs. That extinction event was caused by a natural phenomenon. Now mankind has the power to cause its own extinction. This led me to conclude that the deterrence policies of the United States and the Soviet Union had to be completely foolproof. But even as I reached this conclusion, I feared that it might not be possible to achieve that result.

In October of 1962, my fears were confirmed. At the start of the Cuban Missile Crisis, I was managing an electronics laboratory in California and was called back to Washington to lead a small technical team whose job was to provide President Kennedy with a daily assessment of the operational readiness of the nuclear missiles the Soviet Union had deployed to Cuba. Kennedy’s military advisors were urging him to authorize military action against those missiles. Instead, he wanted to try to resolve the crisis through diplomacy, since he feared that any military action could easily escalate into a nuclear war. Still, he was prepared to take military action before the Soviet missiles became operational, so he was using our input to determine how many more days he had for diplomacy. With the intimate picture I was getting as the crisis unfolded, I believed that every day that I went into our analysis center was going to be my last day on Earth.

Against all odds, Kennedy and Khrushchev were able to reach an agreement before the missiles became operational, but it was a very close call. Kennedy later estimated the chances of the Cuban Missile Crisis ending in a nuclear catastrophe were one in three. But when he said that, he did not know that the Soviets had deployed in Cuba not only the medium-range nuclear missiles that were the cause of the crisis, but short-range nuclear missiles that were already operational. If our troops had invaded Cuba, they would have been decimated on the beachhead with nuclear weapons, and a general nuclear war would surely have followed.

We avoided that tragedy as much by good luck as by good management. But our governments learned the wrong lesson from the Cuban missile crisis. The United States concluded that it “won” because it had more nuclear weapons than the Soviet Union, so we worked to sustain and increase that lead. The Soviets concluded that they “lost” because they did not have enough nuclear weapons, so they began a major nuclear buildup. Both the United States and the Soviet Union apparently thought that more nuclear weapons would put them in a better position to “win” the next crisis. Before the resulting nuclear arms race had run its course, our planet had 70,000 nuclear weapons, and fissile material to build tens of thousands more—enough to obliterate each other and the rest of the planet 10 times over.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union were so focused on building nuclear bombs that neither considered the reality that, although neither Kennedy or Khrushchev wanted a nuclear war, we had almost blundered into one. Neither side focused on the unprecedented level of tragedy that such a war would have caused. But I saw that near-tragedy up close, and I learned a different lesson. I learned that even though our two leaders were doing everything they could to avoid a nuclear war, we came very close to having one—and our deterrence policy would not have stopped it.

In 1977, I became the under secretary of defense for research and engineering, serving in the Carter administration. During my term in office I learned another lesson about the limitations of deterrence. I was awakened at 3 a.m. by a phone call from the watch officer at our missile warning center. He told me that his computers were showing 200 missiles on the way from the Soviet Union to the United States! Happily, he quickly added that he had determined that his computers were in error, and he was calling me to help him determine what was wrong with his computers. But before he had recognized that this was a false alarm, he had called the White House to alert them. We came within a few minutes of the president having to decide whether to launch our missiles in response to this presumed attack. If the president had ordered a launch he would have started a nuclear war by accident!

I learned one clear lesson from my experiences with the Cuban Missile Crisis and the false alarm: The United States’ deterrence policy was not sufficient to prevent a civilization-ending nuclear war. The danger of a nuclear war was not that one leader would suddenly launch a surprise disarming attack—which was what both the United States and Russia were preparing for—but that we would blunder into a nuclear war. The blunder could result from a political miscalculation, as in the Cuban Missile Crisis, or an accident, as in the false alarm. Either of them could have resulted in the end of civilization.

Those experiences taught me that our nuclear policies should be directed toward avoiding such a blunder. Yet in the years since then, we have evolved a deterrence policy that actually increases the probability of blundering into a nuclear war. We have continued to focus our nuclear posture and policies on preparing for a surprise, disarming attack, and those policies actually increase the likelihood of an accidental nuclear war. The response of both American and Soviet leaders to the Cuban Missile Crisis was to double down on their dangerous policies, greatly increasing the size of their nuclear arsenals and maintaining the same policies that almost caused the Cuban Missile Crisis to become an extinction event.

In 1994, I became the secretary of defense and as such had an opportunity to do something about my concerns about blundering into a nuclear war. I made lowering nuclear dangers my highest priority. This was facilitated by the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program, which had been passed before I took office. It would be hard to overstate just how many obstacles there were to implementing that vital program. But Sen. Sam Nunn was at that time the Chairman of the Senate Armed Services committee, and he gave me his full support in implementing the legislation that he and Sen. Richard Lugar had pioneered. As a result, we were able to dismantle 8,000 nuclear weapons during the three years that I was secretary, half in the United States and half in Russia. But reducing nuclear weapons was only part of my goal; the more important part was establishing a friendly, cooperative relationship with Russia. I worked very hard at that.

I met with all key Russian government officials four or five times and with the Russian minister of defense more than a dozen times. We met in Washington, Moscow, Brussels, Geneva, Whiteman Air Force Base, Fort Riley, Saratov Air Base, Kiev, and Pervomaysk. We organized a joint US-Russia rescue training mission; we negotiated an agreement whereby Russia would blend down highly enriched uranium (HEU) taken from former Soviet warheads so that it could be used as fuel for American power reactors; we negotiated an agreement whereby Russia would deploy a brigade in an American division for the peace enforcement operation in Bosnia; we had a hot line on our desks that allowed us to discuss urgent issues as they came up. I had the Russian defense minister as my guest at NATO defense ministers’ meetings; I introduced him to President Clinton and his cabinet officers.

In sum, I was in very close communications with the Russian defense minister, and I used that closeness to facilitate specific joint programs, such as the dismantlement of nuclear weapons in Kazakhstan, Belarus, and Ukraine. But I also used that closeness as a mechanism for bringing our two countries closer together generally, as partners if not as allies. When I left office in 1997, I believed that we were well on our way to dismantling the deadly nuclear legacy of the Cold War, and that the hostility that existed during the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, with all of its dangers, was now behind us.

But that was not to be. A series of US policy decisions in the next decades led to increasingly bitter reactions from Russia. Those included: the expansion of NATO eastward toward Russia; the withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM); and the war in Iraq.

As a result, by the second term of the George W. Bush administration, US-Russia relations had become increasingly unfriendly and nuclear dangers were again a concern. That led four former American statesmen to take a dramatic action: former Secretaries of State George Shultz and Henry Kissinger, Nunn, and I wrote an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal in which we cited the new nuclear dangers and argued that the world should, rather than living with this danger, abolish nuclear weapons.

For a few years the response to our op-eds was very positive, in the United States and worldwide. I was beginning to let myself hope that we might succeed. Just a month after President Obama took office he made a remarkable speech in Prague, where he said: “So today, I state clearly and with conviction America’s commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons.”[1] Later that year Obama negotiated the New START with Russia. It entailed modest reductions in the nuclear forces of both countries but was to be followed by New START II, which would entail much more significant reductions. We were on our way, or so I thought.

But Obama ran into a buzz saw when he tried to get New START ratified. He finally negotiated an agreement with the opposition in which Senate Republicans gave their approval of New START after Obama agreed to an extensive nuclear modernization program. That price was too high in my judgment; it now has the United States on the path of spending more than $1 trillion over 30 years to modernize weapons whose numbers we should instead be seeking to reduce. At that point, Obama stopped pursuing his “Prague agenda,” and the four statesmen who hade been pursuing nuclear abolition halted their joint efforts, too.

I was profoundly disappointed at the failure of Obama’s initiative, but I decided that the problem was too grave for me to simply give up. If we could not abolish nuclear weapons at this time, at least we could take actions to lower their dangers. To encourage those actions I formed the William J. Perry Projectto educate the public on nuclear dangers and to advocate to reduce those dangers.

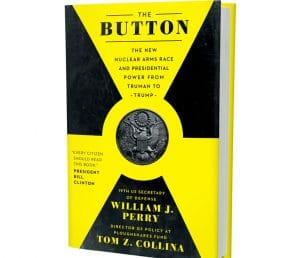

I worked to promote those ideas through op-eds, classes, talks, conferences, online courses, and two books: My Journey at the Nuclear Brink in 2015, and then, in 2020, Tom Collina and I wrote The Button: The New Nuclear Arms Race and Presidential Power from Truman to Trump. It recommends actions the United States can take, like removing the president’s sole authority to launch nuclear weapons, phasing out the country’s intercontinental ballistic missiles, and, until they are eliminated, prohibiting them from being launched on warning of an attack. We see those actions as steps that can keep us alive until we can get to a mindset that allows us to agree to the total abolition of nuclear weapons. The Perry Project is now producing a podcast, At the Brink, that tells the same story, but in a medium more likely to reach younger people. It is hosted by my granddaughter, Lisa Perry, who is an avid consumer of podcasts, like so many others of her generation.

Through all of these actions, I have collaborated with the institutions that have labored for years to promote the same message: the Nuclear Threat Initiative, Ploughshares Fund, and, of course, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Our goal is the same: to mitigate, and in time to eliminate, the danger of a nuclear catastrophe.

At times I get quite frustrated being a “prophet of doom.” And I get discouraged because my warnings of the existential dangers, and the modest recommendations of how to lower those dangers, are not being seriously debated. Even the Doomsday Clock warning, one that seems so easy to understand, has not generated significant political action.

But we cannot give up. The stakes are too high.

It is not hyperbole to warn that a large-scale nuclear war could lead to an extinction event comparable to the one that caused the dinosaurs to die out. While many dinosaurs were killed by the direct effects of the energy released by the asteroid impact, the decisive effect was the nuclear winter caused by the massive burning of the planet’s forests. This nuclear winter lasted for many years and caused the destruction of nearly all vegetation, thereby killing nearly all vegetable-eating animals, which in turn deprived carnivorous animals of food.

In September, we who live in California experienced a small-scale preview of what nuclear winter could look like, caused by smothering smoke from extensive wildfires. In my town of Palo Alto, we actually experienced a “Darkness at Noon”; the smoke sitting on top of the coastal clouds prevented sunlight from getting through, making noon seem like midnight. We experienced this serious blockage only for a day, but it was easy to imagine the widespread crop failure that would result, if it lasted a few years, or even a few months.

In a large-scale nuclear war, hundreds of millions of people would be killed by the direct effects of the blasts, but those blasts would ignite extensive fires as hundreds of cities and surrounding forests burned. In the aftermath of a nuclear war, our limited experience of “Darkness at Noon” in California would be experienced over a wide area of the planet for several years. The least harmful result of a large-scale nuclear war would be the destruction of our civilization. The worst possible result would be the extinction of the human species.

Over many decades in and around both the US and Russian defense establishments, my thinking has evolved, and I have come to strongly believe that it is time to start moving toward the abolition of nuclear weapons, and, until complete abolition can be achieved, to take the smaller but critically important steps spelled out in The Button to lower the risk of blundering into a nuclear war.

In January, Joe Biden will become the 46th president of the United States. He will face many daunting problems: the ongoing pandemic, the battered economy, and a deeply divided nation. All of these will demand his immediate attention, but he must also direct his attention to the entrenched nuclear policies that threaten to end our civilization. As he does so, this paper could be a guide to his thinking.

[1] See https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2017/01/11/fact-sheet-prague-nuclear-agenda#:~:text=%E2%80%9CSo%20today%2C%20I%20state%20clearly,a%20world%20without%20nuclear%20weapons.&text=But%20now%20we%2C%20too%2C%20must,%2C%20’Yes%2C%20we%20can.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten