An ‘Exceptional’ Nation Fails its People as CN’s Editor First Learned 20 Years Ago

•

The failure of the U.S. health system to provide tests for those who need them goes back to the anthrax attacks in 2001 and the Swine Flu epidemic of 2009 in the “exceptional nation.”

By Joe Lauria

Special to Consortium News

The inability of the U.S. healthcare system to provide tests for its citizens at risk of an epidemic, or even a terrorist attack, is unfortunately not a recent phenomenon.

The inability of the U.S. healthcare system to provide tests for its citizens at risk of an epidemic, or even a terrorist attack, is unfortunately not a recent phenomenon.

I was present at an Oct. 18, 2001 press conference with then New York Governor George Pataki at the governor’s Manhattan office. It occurred during the anthrax attacks that followed Sept. 11. Shortly after the press conference ended, word went out that anthrax was found at the office and that those present should be tested.

An 800 number was given to call. After 25 frustrating minutes on hold a doctor answered and told me, “Don’t worry about it. We can’t test you.” I was incensed. Why were those present told to be tested?

“Just forget it,” he said. And then he hung up.

It turned out that New York police, investigating anthrax at other sites in the city, had inadvertently brought anthrax spores into Pataki’s office. Only some of his staff there were tested. All were negative.

But it was a rude awakening. What the government and media report about a situation, creating a sense that government has things under control, may be very far from the truth when you are personally confronted by it.

Then in May 2009, I had traveled back to New York through Chicago’s O’Hare airport, which was said then to be a hot spot for the Swine Flu. Two days after arriving back in New York I developed a late-season, serious flu. It was on the very day President Barack Obama declared a public health emergency. So I tried to get tested for the Swine Flu. This is what happened, as I related in a piece for The Wall Street Journal.

Reporter Tries to Get Tested for Swine Flu

By Joe Lauria

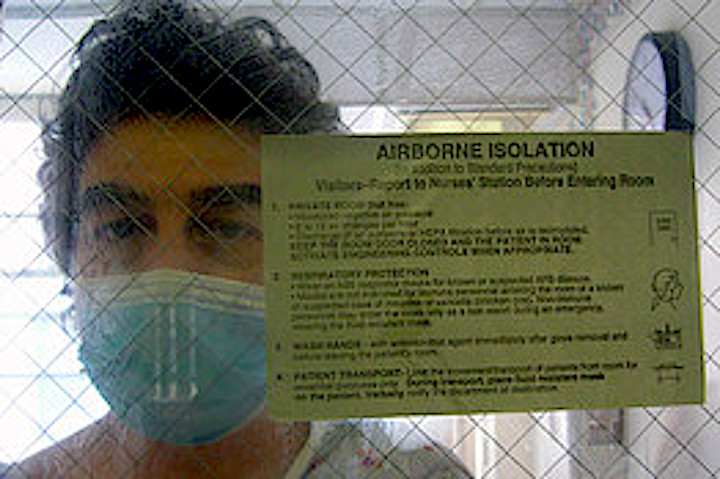

It had been 10 years since I had the flu. But over the past week, I spent four days in isolation at New York’s Montefiore Medical Center after contracting a serious case.I came down with the virus after being stuck for hours at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, which sees more than two dozen flights a day from Mexico.

Forty-eight hours later I had muscle aches, a cough, chills and a 102-degree fever. Authorities only seemed to be giving advice not to “go out.” But few doctors make house calls. Last Sunday night, as my condition worsened, I couldn’t reach my doctor anyway.So I called New York City’s 311 helpline seeking an answer to a simple question: Since President Obama had declared a public health emergency that very day, where could I go in New York City to be tested for the A/H1N1 virus? With several students in Queens already ill and concern growing about its spread, I assumed health authorities had a plan to make testing widely available.

The 311 operator told me to call the New York’s State Health Department hotline, where I was informed to call my family doctor. With my doctor’s office closed, I called an emergency room to ask whether it could test for swine flu. A harried nurse told me to call 311 and hung up. I called the state hotline back to insist on finding out whether there were any facilities for testing. I never got a straight answer, which I took as “no,” there was no plan.By the time I finally reached my doctor by phone on Monday, my left arm had lost its strength. She ordered me to the emergency room. But I first asked her to do a swab for swine flu. “No way, that’s in Washington’s hands,” she said. The state hotline confirmed it: Only the federal government could send a team to test a suspected case.When I arrived at Montefiore Medical Center, the hospital immediately put me into isolation after hearing my story and confirming the fever. A doctor thought he could eliminate the possibility of A/H1N1 flu by swabbing for Type A influenza, which he said included swine flu. The swab came back negative. The doctor said I didn’t have swine flu.Then, two days later, an infectious diseases doctor said it could not be ruled out that I had A/H1N1 because of the imperfection of the test on type A. But she said that by Wednesday, New York City was inundated and refused any more samples unless patients had recently been to Mexico or were in contact with known victims. Another doctor told me they specifically refused mine.I called New York City authorities, who told me they don’t need to test everyone with the A/H1N1 virus and can’t. They said they test only to identify and contain areas of outbreak.Don Weiss, director of surveillance in New York City’s bureau of communicable disease, said authorities do not have the resources to test everyone. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta is working to expand capacity for testing around the country, Mr. Weiss added.“There are probably 10,000 people with the flu in New York,” he said. “We just don’t have the capacity to test that. People with the flu should stay home and call their doctor.”The authorities acknowledged that the interests from a public health perspective, and that of an individual patient, differed. And that creates a public relations issue for city authorities to explain to flu patients why they don’t need to be tested.I’m recovered now, after four days of isolation and because of the hospital’s excellent care. Did I have swine flu? It’s something I thought I’d never know unless I wanted to wait for a test to see if I developed the antibodies for it.I thought I’d just let it rest. Then three days after getting home I called the hospital’s chief medical officer who informed me that after I was discharged my test results came in positive for Type B influenza. I did not have A/N1H1, something I wish I could have found out a lot sooner.Joe Lauria is The Wall Street Journal’s United Nations correspondent.

My discussions with a senior city health official got heated. I could not understand why if people were being told to get tested, there were no tests available. I later learned that this official called the Journalto inform them that “an emotional man calling from a hospital room, complaining about not being able to be tested, claimed to be a Wall Street Journal reporter.” My editors informed him that yes, I was indeed a Wall Street Journal reporter.

The anthrax and Swine Flu experience prepared me for what we are now hearing about the difficulty of being tested for the coronavirus. I am not surprised because I long ago lost faith in a U.S. health care system that has never been prepared for an epidemic, let alone a pandemic. I understand though that calling oneself an “exceptional” nation that is the best at everything might mislead people to believe that it was.

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, Sunday Times of London and numerous other newspapers. He can be reached at joelauria@consortiumnews.com and followed on Twitter @unjoe .

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten