Nomi Prins

Contributor

Nomi Prins is a renowned investigative journalist, author of six books and international speaker. Her advice on financial and banking issues is sought by governments and policy institutes throughout the world...

The Fed Boosts Wall Street, Not Main Street

When Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen left her post in 2018, she secured a spot at the Brookings Institution, a century-old research “think-tank” in the heart of Washington, D.C. Naturally, she also hit the speaking circuit. Her entrée into the upper echelons of revolving-door politics came with a hefty fee.

“Collusion: How Central Bankers Rigged the World” Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

At a swanky locale in the ultra-expensive Tribecaneighborhood in New York City, Yellen soothed a bunch of A-list elites, saying that inflation wasn’t so high and that rate increases wouldn’t come too quickly. In doing so, she was simply following in the footsteps of her predecessor, Ben Bernanke. After leaving the same post, Bernanke launched his speaking career with, among others, a speech in the United Arab Emirates for which he was paid $250,000. This topped his yearly income at the Fed by 25 percent in one go.

While Bernanke scored big in the Middle East, Yellen’s talk was closer to home. Welcome to Wall Street, Janet.

There was a reason for her landing in downtown Manhattan. She assured the well-coifed pack of 1 percenters that she could speak only for herself—it was important to distinguish that she would not be a brand ambassador on behalf of her successor (and once-upon-a-time number two guy) Jerome Powell. Yet, she knew that somehow her words would escape into the public ether.

They would be comforting words for the financial moguls. For the top 10 percent of the country that own 84 percent of the stock market, her remarks invoked confidence that the status quo of cheap money flowing from the Fed would be preserved. The boat would not be rocked. They could continue enjoying their meteoric rise from the depths of the financial crisis and know their money would remain safe after a decade of the Fed’s “quantitative easing” (QE) policies.

And let’s face it, the event went largely unnoticed. For Washington, the “Trump Show” is in town now. For Wall Street, even during the recent volatility waves, times are still relatively good. That’s why, especially now, understanding what is brewing inside and outside the Fed matters.

From the left to the right of the American political spectrum, few are questioning what the connection between the Fed’s largesse and the financial markets really means. The biggest banks have been experiencing largely unregulated, unlimited, support in the form of Fed policy that has nothing to do with saving, or helping, the Main Street economy.

You can look no further than the latest trend over the last year. The sheer record number of stock buybacks since the financial crisis from the banking sector and other corporate sectors is explosive. Heady stock market levels converted an influx of cheap money into a new kind of share value, one predicated on conjured capital.

Last year, the Fed blessed record stock buybacks for its members (private banks) without a word, let alone a demand, about using that money for true Main Street pursuits. The current Fed leader, Jerome Powell, and other incoming high-level Fed appointees have taken that a step further. They have now indicated that they want to further loosen the rules over what banks can do.

This year alone, the ongoing central bank policy (even with a few rate hikes along the way) is on pace to fuel over $1 trillion worth of U.S. S&P 500 corporate stock repurchases. This signals that if a bank—or major company—obtains minimal interest rates when borrowing money, they will borrow more.

They have and will continue to use that fresh debt to buy their own stocks, catapulting their CEOs and executives to ever higher compensation levels. Meanwhile, the taxpayers of America are left with a shrinking middle class and diminished economic upward mobility.

The Shaky Feeling of Being Left Behind

All of this central bank fabrication and market-focused abundance hasn’t reached the masses. According to a new report by Morning Consult, more than half of all Americans are still feeling a squeeze that they attribute to—as I like to call it, post-financial crisis stress syndrome (PFCSD). The middle-class respondents feel the impact the most.

And who did they blame for the recession and economic anxiety? It was nearly a tie—with 73 percent of respondents blaming the politicians and a smidge more than 72 percent blaming the big banks. Contrary to the cheery economist prognosis from the Trump administration and the Fed, 65 percent of those Americans surveyed were worried about another near-future downturn. As a result, they were trying to keep a lid on their own debt accumulation. But for average Americans, debt comes at a far greater cost than it does for banks and corporations.

The scary thing is that household debt is hovering near record highs. The likelihood of a negative impact to people already living on the edge has been baked into the cake of 10 years of emergency cheap money policy that ignited credit card use to make up for stagnant wages and jobs with low benefits.

Central Bank Collusion

The polices that major global central banks—led by the U.S. and embraced by Europe, Japan and England in particular—enacted in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis represented no free lunch. Everything has a price. The issue now is: Who pays? You can rest assured it won’t be the mega banks. Wall Street banks gamed the system, received bailouts, inhaled cheap money, paid minimal fines and carried on with business as usual.

By fabricating trillions of dollars to lavish on the banking system, the consequences (some unintended, or willfully ignored) have real-world repercussions. Central banks became the world’s largest portfolio managers. They boosted asset prices by falsifying demand as a new class of buyers for them.

The prices of those assets rose, and the amount of debt-oriented assets created to fill the demand of those that wanted to purchase them increased as well. Conjured money inflated our asset bubble world. Bubbles can do two things—grow or pop.

Central bank leaders deemed their policies positive for the broad economy. Yet, reports over the years indicated that inequality has grown since QE began. The top 10 percent of income earners have become wealthier and more invested in bubble assets, while the bottom 90 percent have not.

Easy Money Makes Bankers Friends, Life Harder for Others

Since QE went global, the Bank of England, for one, has often had to defend itself from accusations that its policies have increased inequality. A recent study concluded that “nine years of asset purchases that pumped 375 billion pounds ($527 billion) into a faltering world economy didn’t widen inequality after all.”

Although the British central bank does acknowledge that some measures of inequality arose, it stressed that accommodative monetary policy had only a “marginal impact” on that rise. The analysis simply misses the point. Net wealth at the top increased as asset bubbles fueled by QE inflated further.

By sheer math, we can see that those who had access to QE rode the policy to greater gains while everyday citizens struggling to get by did not. They were not a part of the magical relationship between central banks, private banks and markets. That’s the definition of inequality. The rich get richer and everyone else—doesn’t.

In the U.S., the top 10 percent hold about half of their wealth in financial assets, such as stocks and bonds, whereas the bottom 25 percent of the population has more debt than assets. Even the Fed acknowledged that the distribution of wealth has “grown increasingly unequal in recent years.”

In addition, a major recent study from the Bank for International Settlements (or BIS, the central bank of central banks) only confirmed these results. The BIS found that U.S. has become more economically divided, partly because QE has driven financial asset levels higher. That drastic rise in financial assets outpaced the values of savings or median-priced homes, which are critical to lower- and middle-income household wealth accumulation.

Central banks highlight the fact that inflation in the major developed economies hasn’t gone off the charts yet. By making such a claim, they can justify their policies of keeping rates low. But, there has been inflation—in the cost of living versus wages, the cost of health care, education and rents—as well as in those asset values inflated by reams of cheap money.

Meanwhile, not only were big Wall Street banks saved in the wake of the financial crisis, but they’ve clawed back from the abyss and made a killing. Last quarter, most of them posted record profits to kick off the latest earnings season.

Not only that, their profits weren’t just attributable to all the money from the Fed. They got another gift from Washington packaged in the tax law President Trump signed in December 2017.

The new tax law collectively allowed the Big Six banks to save an estimated $3.59 billion during the first three months of 2018. Whereas the average person might have noticed a small drop, or none at all, in tax cuts, the big banks took stellar advantage of what JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon refers to as another round of QE.

A Reversal Could Be Bad, Too

The major central banks have collectively bought $21 trillion worth of assets over the past decade in their quest to keep rates low and asset prices high. The distortive effect of that injection of fabricated money has a multiplying effect. Its biggest trigger has been the borrowing wave.

The Fed’s QE defense—from Ben Bernanke to Janet Yellen to Jerome Powell (the first two from the Obama, and last from the Trump, administration)—is that their actions prevented a Great Depression. They converted a Great Recession into near “full” employment, which should be an income inequality reducer. But, near full employment measures today belie the quality and stability of jobs as well as this bubble effect and grossly subsidized financial system.

Artificially stimulated markets are dangerous because they are built on flimsy foundations that rely on a constant supply of cheap money. Companies that borrowed money in order to buy stocks didn’t have to worry about demonstrating concrete signs of strength. They took on loans and borrowed cheap funds without a real, growth-oriented plan. They had no concern for building higher wages, providing better employee benefits or focusing on business development and long-term stability.

The Fed Is Wrong

The BIS has noted the link between the QE of its own central banks and inequality for some time. In March, 2016, the body reported that:

Our simulation suggests that wealth inequality has risen since the Great Financial Crisis. While low interest rates and rising bond prices have had a negligible impact on wealth inequality, rising equity prices have been a key driver of inequality. A recovery in house prices has only partly offset this effect. Abstracting from general equilibrium effects on savings, borrowing and human wealth, this suggests that monetary policy may have added to inequality to the extent that it has boosted equity prices.

The Fed and other central banks remain in denial. To best understand this negligent position, we can look at the banker who was in charge during the crisis. “The degree of inequality we see today is primarily the result of deep structural changes in our economy that have taken place over many years,” said former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke at a Brookings Institute symposium in 2015.

The statement came just before the Fed began raising rates as slowly as possible—to not upset the asset bubble equilibrium. Bernanke added: “By comparison to the influence of these long-term factors, the effects of monetary policy on inequality are almost certainly modest and transient.”

It’s true that economic inequality didn’t start at the 2008 crisis, and other factors continually bear upon it. But what the central banks did exacerbated the problem over the past decade—as concluded by the Fed’s own analysis.

The Fed and central banks have colluded in the most grandiose fashion. They have set the stage for a more devastating collapse the next time around, because it will be from a higher height of fabricated money. Sadly, it will also give way to even greater inequality than before.

When these institutions reverse their policies, or the financial system implodes again under the weight of risky practices in a largely unreformed banking system, it will be those at the bottom that suffer the most. All the while, those at the top—and their supposed regulators—will again manifest a solution for conjuring money, one that secures their own future at our expense.

Today, central bank collusion is nothing more than a massive “trickle down” subsidy for the financial system and promises for the masses. Only the money doesn’t trickle down, it remains confined to the private banks, central banks and the markets.

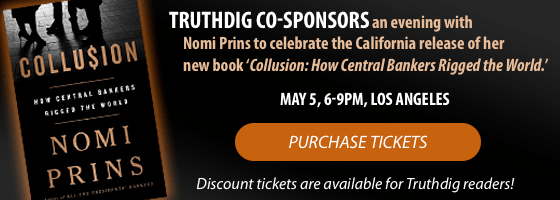

Truthdig is co-sponsoring Truthdig columnist Nomi Prins’ book release eventfor “Collusion: How Central Bankers Rigged the World” in Los Angeles on Saturday, May 5, starting at 6 p.m. Truthdig contributor Greg Palast will be the moderator. Click here for multiple ticketing options, which give Truthdig readers a substantial discount. See a calendar of Prins’ public events schedule around the country.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten