When Slaves and Pirates Struck Terror into the Hearts of the Colonial Powers

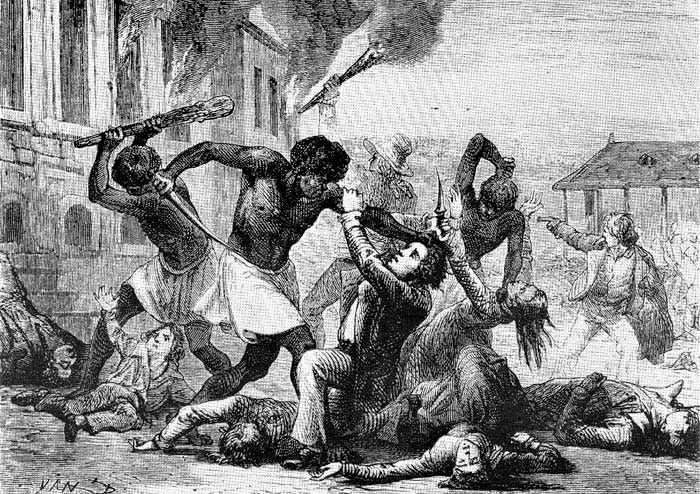

They stormed the plantations before dawn, killing the owners, before seizing a nearby arsenal of gunpowder and rifles.

They struck terror in the hearts of the powerful—the merchants, the lawmakers—even as soldiers hunted them down and killed them, often in gruesome ways.

And despite that punishment, they rose up again and again, gradually eroding the sense of ‘safety’ that allowed the system to exist.

Powered by the unceasing demand for sugar, as well as other products that only the colonies of the New World could provide, the Atlantic Powers —which included Britain, France, and semi-autonomous organizations such as the Virginia Company—built one of history’s largest systems of exploitation. Hundreds of thousands of laborers, criminals, European dispossessed, and Africans were shipped into slavery. These people ended up incorporated into the hierarchy of the growing Atlantic World as a “labor class,” subservient to the ruling powers that had enslaved them.

That labor class, detesting their circumstances, resisted in a number of ways. African slaves are especially noteworthy for the strength of their opposition to enslavement. In his Slavery and African Life, for example, Patrick Manning talks about how “slaves resisted their degradation not only morally, through religion, but physically. Free persons resisted capture. Those captured and shipped to the New World revolted with predictable regularity.” Slave insurrections tore apart Caribbean islands and struck fear in the hearts of slaveowners.

Sailors, who constituted arguably the most important labor force of the Atlantic World aside from slaves, also engaged in insurrections. Piracy and mutiny existed as continual undercurrents within sailor societies. Like the slaves, sailors rose up against their horrific working and living conditions.

Insurrections on land, even if crushed by a colonial military, shook the existing power structure to its foundations; but insurrections at sea largely failed to have a similar impact. Slaves may have seized territory, killed masters, and even overthrown colonial governments, but pirates and mutinous sailors never permanently crippled a British or French shipping route. It was far easier for the ruling powers to maintain order at sea.

This is interesting because those ruling powers would, logically, have far more concentrated military and economic power on land; you’d think it would be easier to maintain control. But as the numerous revolts, insurrections, and acts of unorganized resistance show, the labor class on land was in a far better position to affect the ruling powers’ infrastructure (i.e., production facilities, plantations, and other organs of government and commerce) in ways that, even if not successful, could encourage the first hints of change. Although the Atlantic World was birthed and maintained by sea passages, the freedom for its laboring classes from bondage would come not from actions at sea, but on land.

Throughout the Atlantic World, the precursor to slave insurrections seems to have been chaos or disorder within the existing power structure. In the Caribbean and Brazil, resource-sapping struggles between the Atlantic powers created an opening for internal rebellion. The goal of the insurrectionists, understandably, was to alleviate or escape the horrible conditions that the ruling powers had imposed.

In Jamaica and the Guianas, huge slave revolts rose up that were so massive, and so captured the popular imagination, that they would even influence the debate over abolition in England. Throughout South America, plantations were set to the torch; in the Caribbean islands, former slaves established black autonomy, protecting themselves against colonial military with forts, knowledge of the swamps, and military prowess.

With their greater numbers, distance from the power centers of Europe, and control over the means of production for sugar, tobacco, and other products, slaves were sometimes able to muster longer-term rebellions. Even if these insurrections did not succeed (as in St. John in 1733, crushed by French and Swiss troops), they struck fear that had permanent effects on the institutions of the ruling powers.

Slaves in the American South also engaged in widespread resistance. These actions included stealing hogs, crops, and other property from their plantations; arson and the occasional murder; refusing to submit to the whip, and feigning illness. Poisoning masters, which provoked terror among whites in the Caribbean, was also utilized by slaves in continental North America. While these methods were not effective in freeing the slaves in the United States, it sparked a fear among the upper class that helped slowly fray at the institution of American slavery.

The Battle at Sea

From the 1609 Bermuda rebellion (following the wreck of the Sea Venture) to the constant germination of pirate societies, sailors also fought the conditions imposed upon them. Navies, so important to the maintenance of empire, exerted a violent brand of terror and control over their sailors, whom they regularly exploited to a grievous degree; a number of the sailors, sick of the lack of pay and good living conditions, would consequently turn to piracy and mutiny.

Unlike their counterparts in the Royal Navy, some pirate crews acted in strikingly democratic ways, electing officers, dividing loot equally, and establishing a somewhat-fair criminal code. It was easier for rebellious sailors, whose groups were relatively small in number, to operate in a democratic fashion; pirates, privateers, and mutineers incorporated all of the Atlantic World’s downtrodden and dispossessed into their ranks, including slaves and women.

These multinational, multiracial crews initially filled governments and navies with dread. In 1718, Colonel Benjamin Bennet wrote that “I fear they [pirates] will soon multiply for so many are willing to [join] with them when taken.” Pirates struck fear into traders and did massive financial damage to the various maritime trades, as well as the revenues of the Middle Passage.

Such aggression could not be allowed to stand; although governments sometimes tried to conscript pirates as “privateers” tasked with raiding other countries’ supply routes, piracy continued to grow throughout the 1600s and early 1700s (the so-called ‘Golden Age of Piracy’) into a substantial threat against the existing power structure. This maritime radicalism, once the ruling powers had deemed it a problem that demanded attention, was quickly crushed. After hundreds of hangings, the destruction of pirate fleets and societies, and violent rhetoric from various officials, piracy was largely dead by the 1720s.

The small size of the average pirate “cell” might have worked against these sailors. Relatively tiny groups may have facilitated a democratic system of rule, but it also prevented mutineers from effectively resisting the military establishment; this is in sharp contrast to slave revolts, with their hundreds or thousands of people who could assemble militarily and fight the ruling powers on their own terms.

Constant Struggle

Only when sailors participated in insurrections on land did they achieve a degree of success not present in sea-based mutiny and piracy. For example, the failed New York Conspiracy of 1741, in which sailors participated, frightened colonial leaders in ways that maritime radicalism never did. The incident of the Sea Venture in 1609, in which a group of shipwrecked sailors and other laborers attempted to remain on Bermuda rather than be shipped to Virginia, could likewise be considered a successful resistance.

Pirates’ attacks on the Middle Passage may have robbed slavers of some revenue, but it did not affect the course of slavery; abolition and emancipation occurred due to actions on land, powered in part by the subjugated peoples themselves. The spirit of piracy and sea mutiny was largely crushed after a certain point, but the spirit of insurrection on land never was. Although Tacky’s Revolt on Jamaica was obliterated, for example, the constant currents of insurrection and rebellion (far more sustainable on land than at sea) helped ensure that the slaves throughout the region would eventually be emancipated.

The institutions of the Atlantic World, from the European states to the sugar plantations, maintained a rigid hierarchy of power, from king or plantation owner down to laborers such as slaves and sailors. At moments, this structure may have seemed impossible to challenge. But in the success of these rebellions (however temporary), we see that this hegemony indeed had limits. The downfall of the colonial regimes of the Atlantic World came from the source of their supposed strength: the labor class and the exploited.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten