Israel Set to Block Palestinian Unity

As the Palestinians seek unity between their two rival factions, Israel stands ready to obstruct the process and thus maintain its complaint that the Palestinians remain divided, notes ex-CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar.

The latest attempt at reconciliation between the competing Palestinian parties Fatah and Hamas has produced a preliminary agreement that Egypt brokered and was announced earlier this month. The reasons for movement on this subject at this time involve motivations of the Egyptians, who want to use improved relations with authorities in the Gaza Strip to help defeat extremists who are active in the Sinai Peninsula.

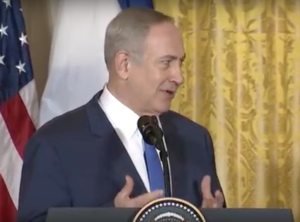

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu making opening remarks at a joint White House press conference with President Donald Trump on Feb. 15, 2017. (Screenshot from White House video)

Egypt, which has taken the side of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in their dispute with Qatar, also hopes to reduce Qatari and Turkish influence among the Palestinians. The evolving motivations of Hamas also are pertinent. The group has come to realize how thankless a task is the governing of the Gaza Strip, which is beset by an Israeli semi-blockade and unrepaired damage from Israel’s military assaults.

The preliminary agreement is little more than a joint statement of aspirations and a timetable for resolving outstanding issues. The main substantive advance has been Hamas’s declared willingness to turn over administration of the Strip to the Fatah-controlled Palestinian Authority (P.A.). Laborious negotiations lie ahead to resolve questions such as how to integrate two separate cadres of civil servants.

Historically based ill will and mistrust also must be overcome. Palestinians, just like other nations, have politics characterized by ideological and generational divides, some of which can be sharp. Anyone familiar with U.S. politics, with its considerable ill will and sharp divides, ought to find this easy to understand.

An additional complicating factor of late is the ambition of Mohammed Dahlan, a former Fatah security chief in Gaza who has been leveraging his friendship with the UAE (where he has lived in exile) to re-insert himself in Palestinian politics and whom P.A. president Mahmoud Abbas considers a rival for power. Complete Palestinian reconciliation between Fatah and Hamas would be uncertain even if the matter were left entirely to the Palestinians themselves.

Israel’s Obstruction

But reconciliation will not be left to the Palestinians themselves, just as it has not been left to them in the past. Israel has actively and repeatedly thwarted reconciliation. In addition to everything Israel has done to undermine the authority and credibility of the P.A. and to sustain dire extremism-breeding conditions in Gaza, it has taken more direct action to derail previous efforts at reconciliation whenever they showed any promise of success. Israel has employed one of its favorite ways of punishing the P.A., withholding taxes that it is supposed to pass on to the P.A., to pressure the P.A. into dropping previous efforts to reconcile with Hamas.

Palestinian boys prepare to welcome Women’s Boat to Gaza, which was intercepted by the Israeli naval blockade on Oct. 5, 2016.

For the right-wing government of Israel, derailing intra-Palestinian reconciliation helps to sustain the theme that Israel “doesn’t have a negotiating partner for peace.” If that government really wanted such a partner, then it would be supporting rather than derailing steps toward developing a unified Palestinian leadership that could speak most credibly for all Palestinians and to negotiate on their behalf.

But the government of Benjamin Netanyahu doesn’t want such a partner. It instead wants rationales for indefinitely kicking the prospect of meaningful peace negotiations into the future, while Israel’s colonization project cements its hold on the West Bank. The “no negotiating partner” meme has become sufficiently entrenched in Israeli public perceptions to make the government’s strategy politically sustainable.

For now, Netanyahu’s government appears to have concluded that there are enough obstacles in the way of full Fatah-Hamas reconciliation that active derailment measures such as use of the tax weapon can be kept in reserve. Meanwhile, Israel is voicing old familiar demands (along with some new ones), which are highly unlikely to be met, as preconditions for negotiating with any unified Palestinian leadership that results from reconciliation.

One of those demands is an explicit Hamas recognition of Israel. This has always been an odd demand in that recognition of states is something that comes from other states, not from parties or movements. And if parties and movements were to be considered part of the recognition business, why shouldn’t recognition be reciprocal? Where is the Israeli declaration affirming a right to exist for Hamas?

In any event, the leadership of Hamas has long made it evident that it aspires to political power in a Palestinian state that would live side-by-side, and in an indefinite truce, with Israel. Earlier this year Hamas issued a new political statement making clear that it accepts a Palestinian state limited to the 1967 boundaries.

Repeating Old Arguments

The Israeli government likes to point to more extreme hortatory language in Hamas’s earlier charter, but this is really no different from charter-related matters that everyone went through a quarter century ago with the Palestinian Liberation Organization, which had a similar-sounding charter. As the Oslo process in the 1990s demonstrated, such hortatory documents are no barrier when there is a will to negotiate on both sides. Besides, if we are to worry about charters, then there is at least as much of a problem with the charter of Netanyahu’s Likud party, which categorically rules out any right to exist for any Palestinian state, no matter who leads it.

An Israeli soldier prepares for a night attack inside Gaza as part of Operation Protective Edge, which killed more than 2,000 Gazans in 2014. (Israel Defense Forces photo)

Israel also demands that Hamas completely disarm. This is coming from a government that has used its far superior military might to inflict highly asymmetric damage in repeated assaults on the Gaza Strip. In the last such foray, Operation Protective Edge in 2014, more than 2,200 Palestinians were killed, two-thirds of whom were civilians, against 73 Israeli deaths, all but six of whom were soldiers.

Of course Hamas is not going to disarm unilaterally in response to Israeli demands, and certainly not in the absence of any reciprocal pledge by Israel to forswear violence against Palestinians. If it did, it would lose further support from citizens of Gaza, who see the rubble from Protective Edge still surrounding them. And it is not as if Hamas is now using what military means it has to inflict harm on Israel.

As David Makovsky of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy notes, “Israeli officials admit that Hamas has not fired a shot against their country since the 2014 war.”

The Trump administration’s two-faced posture toward all this is reflected in the headlines in the print editions of the New York Times and Washington Post, on the same day and reporting on the same Egyptian-mediated preliminary agreement between Fatah and Hamas. “Seeing Opening for Wider Peace, U.S. Aids Palestinian Talks” reads the Times. The Post’s headline is “U.S., Israel balk at Palestinian reconciliation, insisting Hamas must disarm”.

The U.S. policy that flummoxed the headline-writers is ostensibly one of working toward a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict but in fact is one of signing on to the Netanyahu government’s postures, except for the mildest bit of tut-tutting over that government’s accelerated construction of Israeli settlements in occupied territory. As with Israel’s policy, the U.S. policy supposedly bemoans weakness and division on the Palestinian side but in practice sustains it. And also as with Israel’s policy, the longer-term outcome is not the deal of the century but instead an indefinite kicking of the peace can down the road.

Makovsky aptly observes that “the United States will not be putting forward any peace plans or engaging in high-stakes Middle East diplomacy until the Gaza situation is clarified.” And as long as Israel stands ready to throw sand in the gears of Palestinian reconciliation, the Gaza situation will never be clarified. Makovsky further accurately observes that “no publicly discernable progress has emerged” from the talks Trump’s envoys have had this year in Jerusalem and Ramallah, and that Trump made no mention of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in his speech last month at the United Nations General Assembly.

Expect Israel to start throwing sand if the reconciliation gears acquire some momentum. Expect also that the Trump administration will acquiesce in Israel’s actions.

Paul R. Pillar, in his 28 years at the Central Intelligence Agency, rose to be one of the agency’s top analysts. He is author most recently of Why America Misunderstands the World. (This article first appeared as a blog post at The National Interest’s Web site. Reprinted with author’s permission.)

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten