Forget Biden’s Bust of Cesar Chavez: Hunts Point Strike Is the Bold Labor Action the Country Needs

Essential workers, ravaged by the pandemic as their bosses raked in millions, organized from the bottom up and won concessions.

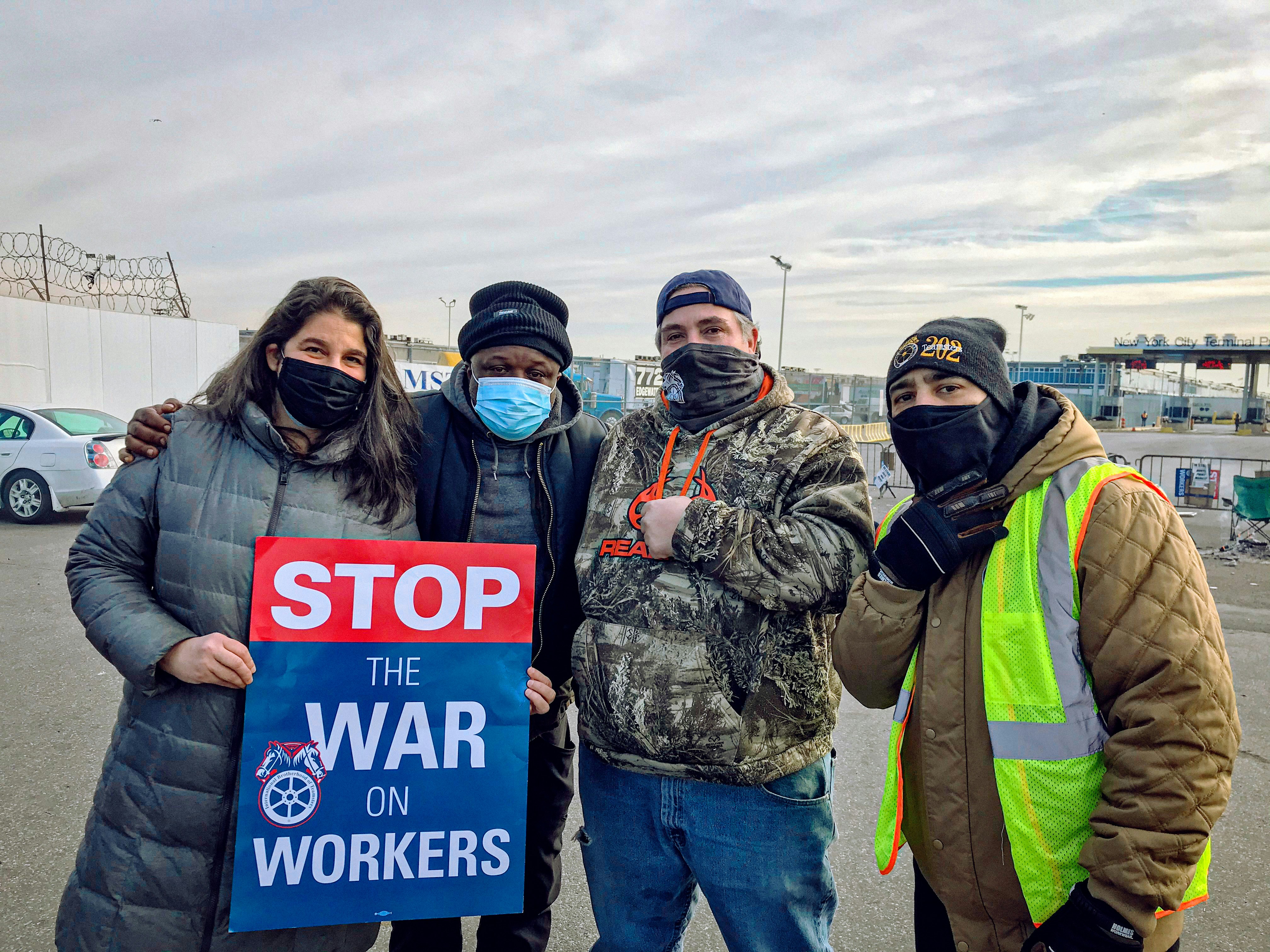

Gerson Castillo, Hunts Point worker and a member of Teamsters Local 202, is seen during the strike at Hunts Point Produce Market in the Bronx, N.Y., on Jan. 18, 2021.

Photo: Courtesy Alex Moore/Teamsters Joint Council 16

AS THE FIRST images of President Joe Biden’s Oval Office began to circulate online, a prominently placed bust of labor and civil rights leader Cesar Chavez drew swift comment. Nestled amid Biden family photos behind the president’s desk, the bronze statuette appeared to signal a commitment to the Latinx and worker struggles for which Chavez, founder of the union that would later become the United Farm Workers of America, fought.

Far from the inaugural pomp, meanwhile, hundreds of striking workers at the Hunts Point Produce Market in the Bronx, New York, were already demonstrating what the fight for workers’ rights looks like on the ground for those forced to work in perilous proximity throughout this pandemic.

Hunts Point is part of New York City’s most important food hub, handling most of the fruit and vegetables that get sold throughout the five boroughs. Its workers earned praise and press coverage for keeping the city fed as the public health crisis threatened supply chains.

Having risked their lives throughout the last year, the workers, members of Teamsters Local 202, sought a raise of a mere $1 per hour in their new contract. Negotiations broke down when management refused, offering an hourly boost of only 32 cents. The union members voted to go on strike, starting last Sunday — the first strike at the Hunts Point market in 35 years.

“We worked through a pandemic. I’ve been working here for 28 years, and it’s hard work,” said Ismael Cancela, a warehouse worker and Local 202 member. He told me that the offer of a 32-cents-per-hour-raise was a “slap in the face.”

After nearly a full week on the picket line, Teamsters leadership announced a tentative agreement had been reached. On Saturday morning, the strikers voted to approve their new contract, which includes a $1.85 wage increase over three years and an end to any out of pocket payments for family healthcare plans. While not the full $1 raise they had demanded and deserve, there can be little doubt that the conditions of the contract were considerably improved through the strike. Concerns among supporters have arisen about whether union leaders were willing to settle too early — a reminder of the importance of rank-and-file decision making — but the workers were nonetheless celebrating the new contract as a victory.

“We’re only essential when it suits them. There were guys who died. I got the virus and brought it home to my family.”

Following decades of anti-worker, anti-union labor laws established in this country, the Hunts Point strike comes at a time of robust and potent labor organizing. Last February, the House passed an omnibus labor reform bill, the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, which would overturn a number of anti-worker Supreme Court decisions.

The strike at the market, aimed at a key chokepoint of commodity circulation, underlines the necessity of collective action, the solidarity it requires, and the critical role of strong unions. This sort of high-stakes, hard-fought labor action — which entails significant sacrifices from workers — is the least that powerful business owners should face when workers are deemed “essential” but treated as disposable.

“We’re only essential when it suits them,” said Darren Brenner, a 52-year-old warehouse worker who has been a Teamsters member at the market for 31 years. “There were guys who died. I got the virus and brought it home to my family,” he told me on Thursday afternoon, standing at the barricaded entrance to the distribution center with a few dozen co-workers, maintaining the picket line through the quieter day shift. Brenner said that while he and his family fully recovered from Covid-19, numerous other co-workers “never came back” from the disease.

According to a Local 202 spokesperson, hundreds of workers were infected with Covid-19, and six died. “Our jobs are always dangerous. For them to offer us 32 cents — to think that’s what we’re worth to them. It’s an insult.”

Photo: Courtesy Alex Moore/Teamsters Joint Council 16

THE BRONX’S OWN Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez helped draw broader attention to Hunts Point, eschewing Washington, D.C., on Inauguration Day to join the picket line. And Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., while iterating as a thousand mitten-clad memes across social media on Wednesday, tweeted his support for the strike. “Essential workers should not have to go on strike for decent pay,” he wrote.

When I spoke to Teamsters on the picket line on Thursday, a number expressed gratitude for the politicians who had lent their voices to the effort. The focus of their thanks and praise, however, went toward other unionized workers who had joined the picket line and contributed supplies and funds: from nurses and teachers to sanitation workers.

“The message this solidarity shows to workers in the city, in the whole country, is very powerful,” said Danny Kane, the president of Local 202 since 1999.

The strike drew up to 500 supporters to the picket line’s night shifts. Tensions escalated in the early hours of Tuesday, when more than 300 police officers in riot gear charged the picket line and arrested five people for allegedly obstructing traffic. The Teamsters condemned the arrests in a tweet, then immediately returned to their stated key message: “These essential workers deserve their $1 raise.”

The majority of Hunts Point workers have an average base salary between $18 and $21 an hour; some earn as little as $15 per hour. Meanwhile, as a statement from the Teamsters noted, “Employers in the market, who collectively bill billions of dollars in annual sales, received more than $15 million in forgivable PPP loans during the pandemic.” The food hub regularly pulls more than $2 billion in yearly revenue, according to the New York City Economic Development Corporation.

Amid this windfall, Jamie Bermudez, a Local 202 member, highlighted the suffering endured by workers like himself, who fell seriously ill during the pandemic. “I almost died from it,” said Bermudez, who was hospitalized and sick with Covid-19 for a month. “I couldn’t breathe, I couldn’t eat.”

Read Our Complete CoverageThe Coronavirus Crisis

Read Our Complete CoverageThe Coronavirus CrisisNumerous workers stressed that while their treatment throughout this health crisis may have galvanized the decision to strike, a meaningful raise was necessary under any circumstances. “Every price is going up, except our wages,” said Bermudez. As the strikers spoke of colleagues lost to Covid-19 — “another Jamie, and Victor!” — a huge Pepsi truck drove by, honking in support. A white truck pulled up to the barricades, and workers unloaded wood pallets to burn for warmth in the freezing late January days and nights.

Photo: Natasha Lennard/The Intercept

ALONGSIDE OTHER UNIONIZED workers, the strike garnered support from a spread of activist communities and organizations, including the Democratic Socialists of America, immigrants’ rights groups, Black liberation fighters, anarchists, and anti-fascists. Angela Fernández, a leading immigrants’ rights attorney and activist, joined the picket line, having supported Teamsters facing immigration challenges in the past.

Fernández, who is a New York City Council candidate seeking to represent neighboring Washington Heights, Inwood, and Marble Hill, told me that the intersection of immigrants’ rights and labor struggle can never be overlooked. “We need to understand the deep-rooted connectedness and intersectionality of this work,” she said, stressing that the “war on unions,” which she credits Ronald Reagan for starting, has been detrimental for working people everywhere.

The wealth of corporations and their owners compared to the economic hardship faced by those whose labor they exploit has always been intolerable.

Most of the striking workers live locally. Hunts Point has one of the highest concentrations of Latinx residents in all of New York City, and almost half of the area’s population lives below the federal poverty line. Organized labor, Fernández said, “is ripe for a resurgence” with major strikes as an indispensable locus of “public agitation.”

While thrown into ever sharper relief by the pandemic, the wealth of corporations and their owners compared to the economic hardship faced by those whose labor they exploit has always been intolerable. Cesar Chavez’s legacy is complicated by his deeply flawed opposition to undocumented immigrants entering the U.S., but his statement that “we draw our strength from the very despair in which we have been forced to live” speaks to this pandemic moment and the workers organizing within it.

It should not take the high risks and pay losses of a strike to win a decent wage. But it’s plain as day that workers’ rights, protections, and livelihoods won’t be delivered simply because a liberal centrist president puts a statue of a famous union leader in his office. As ever, the workers and liberation fighters on the front lines will lead the way.

Update: January 23, 2020, 1:49 p.m. ET

This story has been updated to include some specifics of the strike-ending contract and workers’ vote to approve it.

https://theintercept.com/2021/01/23/covid-nyc-hunts-point-strike/

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten