Whitewashing Dr. King

“King and the Other America: The Poor People’s Campaign and the Quest for Economic Equality”

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

“King and the Other America: The Poor People’s Campaign and the Quest for Economic Equality”

A book by Sylvie Laurent

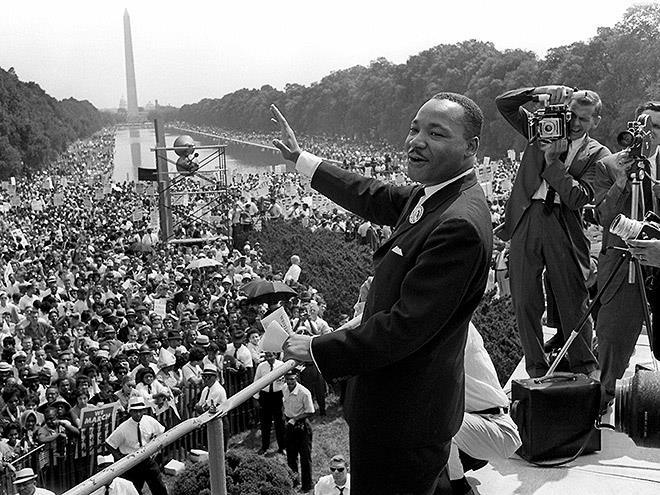

“I Have A Dream!” Those majestic words, spoken by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963, have entered the history books as the single most remarkable rhetorical flourish of modern civil rights history. Along with the other 250,000 people in attendance, I was mesmerized by King’s magnificent sermon. My presence at the march and listening to King have remained a highlight of my life. When I play the entire speech to my university classes, I still feel an enormous wave of emotion.

But King was much more than his dream. Indeed, his dream has been co-opted to the point that he and the dream have been made almost synonymous in popular culture. Every February, during Black History Month, those glorious words are repeated on television almost ad nauseam, inducing a state of reverential patriotism that obscures and distorts the genuine legacy of King.

Every major city in the United States has streets and schools named for King. Throughout the world, his image appears on stamps, picture books, and objects like cups and saucers. Prints, paintings and murals with his face adorn public buildings and private businesses. The popular King memorial in Washington, D.C., along with others throughout the nation and the world, makes no mention of past and continuing racism. They merely encourage audiences to venerate a great patriot—which indeed he was, but for reasons that millions of Americans and others can hardly imagine.

French cultural historian Sylvie Laurent, author of an intellectual and political biography of King, warns of the political manipulation of memory. This is especially tragic in the case of King, whose legacy has been so distorted that he even appears, as she notes, in a commercial for trucks. It is dismaying that one of America’s giant radical figures has become part of a semiofficial mythology that inhibits people from any understanding of his structural critique of American capitalism.

That critique is the focus of Laurent’s new book,”King and the Other America: The Poor People’s Campaign and the Quest for Economic Equality.” This powerful work invites a major reconsideration of American civil rights history, the significance of the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968, and especially of King’s deeply egalitarian socialist vision of society. The book transcends and negates traditional notions that King was a civil rights leader committed exclusively to the liberation of his African-American people. Without ever abandoning that objective, he expanded his range of activism in pursuing a vision of a fair and just society for all oppressed people.

Laurent’s book above all restores King to his rightful and still profoundly under-recognized place in the history of militant African-American liberation figures. Contrary to the misleading image of King as a benign apostle of peace and love, the author shows him to be a militant in the tradition of Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson and others who combined the struggle against American racism with a deeper commitment to political, economic and social change.

A key feature of this book attempts to locate exactly where King falls within the spectrum of American and international radicalism. He was not an orthodox Marxist, but as the text makes clear, he was influenced by a Marxist worldview—a vision dramatically contrary to the American political manipulation of memory that has falsely made him into a patriotic and commercial icon.

Click hereto read long excerpts from “King and the Other America” at Google Books.

Locating King’s political ideology precisely is actually a complex task. He developed his political and social vision over the years from multiple sources. A committed leftist radical, especially near the end of his tragically short life, he was nevertheless always a committed Christian and a devoted, irrevocable adherent to Gandhi’s vision of nonviolence. He drew much of his profound commitment to racial and social justice from the teachings of Reinhold Niebuhr and from the broader tradition of the Christian social gospel. “King and the Other America” addresses the intricate features of his political and moral vision at great length. Laurent’s treatment of various figures and institutions that influenced King is highly detailed and often fascinating, but most general readers may find themselves anxious to move on to the Poor People’s Campaign and to King’s prescient vision of a multicultural, multiracial coalition to seek a radical redistribution of wealth and power in America.

The definitive repudiation of King as the “nice, peaceful civil rights leader,” venerated while used to underpin and actually advance American repressive political, racial and commercial interests, is the most valuable and enduring contribution of the book. Laurent draws on King’s own writings to illuminate his radical critique of America’s systemic flaws and its fundamental economic inequalities that affected blacks, other communities of color and millions of poor whites.

Laurent’s selections are especially useful. She repeatedly cites King’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail” and his book “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?” to illustrate his deeper radicalism. These sources have been accessible to the public for many decades, and I have regularly recommended them to my students for many years. Tellingly, Laurent also reprints a paragraph from King’s historic speech at Riverside Church in New York, publicly condemning the Vietnam War. King was the first major civil rights leader to oppose that grotesque war, another sign of his far more radical political vision. In November, I assigned the entire speech to my UCLA class of 150 students; not one had heard it, although one or two students had heard ofit.

To underscore his radicalism, King deliberately eschewed electoral politics and collaboration with (and inevitable co-optation into) the Democratic Party. Quoting from “Where Do We Go From Here,” Laurent shows King’s uncompromising view of protest and street agitation over elections and party politics:

Everything Negroes need… will not magically materialize from the use of the ballot. . . . In the future we must become intensive political activists. . . . Most of us are too poor to have adequate economic power, and many of us are too rejected by the culture to be part of any tradition of power. Necessity will draw us toward the power inherent in the creative use of politics.

That vision resonates in the early 21st century. King’s view reveals the classic demarcation between those who choose (primarily) to work within the established capitalist system and those who oppose it (primarily) on the streets. That, as much as anything else, revealed his most fundamental values as a political dissenter.

Much of this powerful volume is devoted to the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign. Laurent brings this movement centrally back into the history of 20th century American social protest. As she notes, it was to be the culmination of King’s social thought and his unyielding commitment to a truly egalitarian society.

King’s support in 1968 for the Memphis sanitation workers, in their struggle for better pay and working conditions, reflected his clear understanding of the intersection of race, class and labor. Memphis garbage collectors were exclusively black. They worked in conditions of extreme neglect and abuse. He saw the Memphis struggle as a necessary steppingstone to the campaign in Washington.

His horrific assassination on April 4, 1968, in the midst of his efforts in Memphis ended his leadership in the Poor People’s Campaign. Laurent perceptively reports that his death both crippled and reinvigorated the movement for social change. The convergence of race, class and labor activism led to the Poor People’s Campaign gathering in D.C., featuring a class-based Economic Bill of Rights calling for a national right to an adequate income, and, above all, the right not to be poor as a humanright. It was, in short, a plan comparable to the 1948 postwar Marshall Plan, a response to the glaringly unequal distribution of wealth and power in the United States.

It is impossible to know what the Poor People’s Campaign would have been had King lived to lead it. When people converged on Washington, the main leadership came from King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Ralph Abernathy, King’s longtime close associate, succeeded to the SCLC presidency and led the campaign. Other notable SCLC figures included James Bevel, Hosea Williams, Andrew Young, Walter Fauntroy, and Jesse Jackson, who was “elected” mayor of the Resurrection City, the name and site of the campaign’s encampment on the Washington Mall.

These men are well known in civil rights and contemporary American political history. The campaign also included representatives from the American Indian community, from the Puerto Rican community, from white coal miners in Kentucky and West Virginia as well as Myles Horton from the legendary Highlander Folk School, and from the Chicano community. Among the latter were Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales and Reies Tijerina. These two men played huge roles in the Chicano movement, but have been largely ignored in standard U.S. history texts.

The Poor People’s Campaign also attracted major endorsements from religious, labor, and various civil rights and social justice organizations. As this volume reveals, Resurrection City had substantial personality conflicts among leaders and residents, intercoalition squabbling, racial tension, tactical disagreements, and general demoralization resulting from problematic living conditions, including incessant rain and mud. There were also far too many unsuccessful attempts to meet with members of Congress to present the Resurrection City residents’ demands. Eventually, on June 24, 1968, the police arrived, cleared the camp, and arrested the remaining demonstrators, including Reverend Abernathy.

These difficulties are chronicled in sometimes excruciating detail; only highly specialized social protest historians and others with compelling interests in that specific movement will care to recall the painful details of its demise. The most enduring takeaway is the legacy of King’s vision of a multiracial coalition to attack poverty and inequality at their structural foundations. That vision, above all, is why he must be seen now, more than a half century after his death, as a genuine revolutionary, not a smiling black face to adorn banners and posters for “feel good” parades and marches while millions of Americans merely have another vacation day each January.

Laurent ends her book on a hopeful note, calling attention to contemporary groups and individuals in the United States who are working for King’s vision of a redistributive state that works against racism, militarism, sexism, and economic injustice. She identifies Black Lives Matter, supporters of Bernie Sanders, Moral Mondays’ participants under the leadership of Rev. William Barber, and others. She is absolutely correct in demanding that we resume the unfinished work of the Poor People’s Campaign. These are perilous times. Donald Trump did not create American oligarchy and fascism, but he has abetted both. Women, LGBTQ activists, people from racial and ethnic minorities, environmentalists, progressive politicians, and all people concerned about a society in which all people can live decent and dignified lives must mobilize rapidly to secure the genuine legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King. This important book encourages us in that direction. American democracy and the entire planet are at stake.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten