The MH17 Trial: The Dangers of Presuming the Fairness of a Geopolitically-Driven Enterprise

Inspection of the MH17 saga teaches us, in the first instance, never simply to presume that an enterprise that appears to have the status of an officially supported and endorsed international legal proceeding must on that account be above reproach.

AMSTERDAM — November 2020 saw the conclusion in Schiphol, the Dutch airport near Amsterdam, to the pre-trial hearings in the case being brought by the Dutch Prosecution Service against three Russians (Igor Girkin, Sergey Dubinskiy, Oleg Pulatov) and one Ukrainian (Leonid Kharchenko), former military leaders of the Donetsk People’s Republic. They were charged with the delivery of a Russian Buk-Telar missile launcher that was allegedly used by separatists in eastern Donbass to shoot down civilian Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 on July 17, 2014, with the ensuing loss of 298 lives.

Following the Court’s consideration in March and April 2021 of defense requests for further investigation, which it would allow, the main trial itself was scheduled to begin on June 7, 2021, in the District Court of The Hague. Regardless of its outcome, I shall argue that this trial and all the major stages that preceded it – notably, the Dutch Safety Board (DSB) investigation of the “facts” (see final report here) and the Dutch-led Joint Investigation Team’s (JIT) determination of criminal responsibility (see final report here) – remain a very troubling basis for the pursuit of justice.

In the unlikely event that the court should find in favor of the defense, it would in effect concede deep processual flaws of the system that brought it into being. In addition to the propaganda functions of a show trial, commitment to the procedure has the attraction of (falsely?) identifying a culpable party from whom reparation may be sought on behalf of victims and, if judgment of reparation be made, establishing a pretext for later aggression or a negotiation chip, as was the case in the Libyan Lockerbie incident.

A stacked deck

Only one of the four men charged – Oleg Pulatov – will be represented in court, although he himself will remain in Russia. At the time of writing, it is not certain that his attorneys will have had an opportunity to visit him. Russian law does not allow the extradition of its citizens for hearings outside of Russia. Russia’s offer to hold the trial in Russia was rejected, predictably. But there are far more significant flaws to the proceedings as currently constituted. One member of the JIT — Malaysia, headquarters of the owner of MH17, the flag carrier Malaysia Airlines — was not admitted to the JIT until 2015, months after it had been constituted, and has rejected the findings of the JIT.

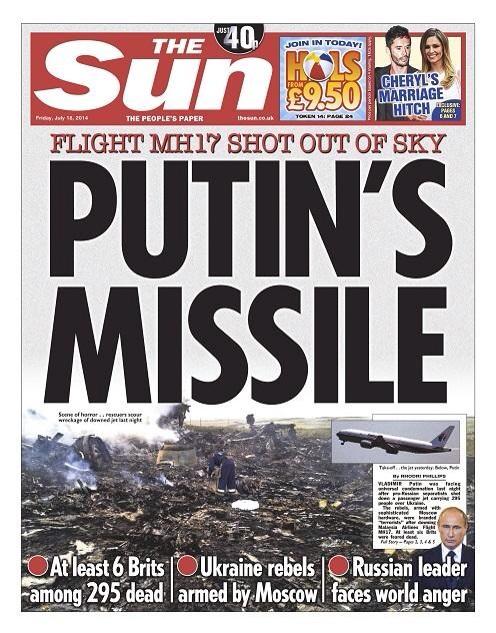

The prime minister of Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad, professed considerable skepticism about the proceedings and the trial, arguing that from the start Russia’s guilt has been presumed while never proven. Western mainstream media coverage of the incident — fed with a narrative prepared within six hours of the crash by the Ukrainian intelligence service (SBU), whose business is the protection of Ukrainian national interests — presumed Russian guilt from day one, best exemplified by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation and the headline of its most popular British newspaper, The Sun: “Putin’s Missile,” on the morning after the crash.

Murdoch’s The Sun, wasted no time determining who was to blame for the downing of MH17

Western mainstream consensus corrupts the popular historical record, as is evident in dubiously verified Wikipedia accounts that generally emerge at the top of related Google searches. Within eight days of the crash, the Dutch foreign minister said that the European Union (EU) would increase existing sanctions against Russia, blaming the separatists for the crash, and the EU piled on further sanctions in 2019. Continuing in similar vein six years later on April 1, 2020, the Dutch minister of justice and security declared his support and that of his ministry for the conviction of the Russians standing trial — an announcement he made during a ceremony honoring senior Dutch prosecutor Fred Westerbeke, who had led the DSB’s inquiry into MH17

Setting up the false narrative context

The persistence of Western mainstream presumption had contaminated public opinion on top of its already pervasive anti-Russian sentiment in media coverage of the U.S.-backed coup in Kiev against the government of democratically elected President Viktor Yanukovych, earlier that year in February 2014, and the questionable Western media presumption that the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation in March 2014 was an aggressive invasion of Ukrainian territory.

The facts were different. Russia had a right, by treaty with Ukraine, to maintain up to 25,000 troops in Crimea to serve its naval base in Sevastopol, which it leased from Ukraine. In other words, Russian forces were already present in Crimea; they did not need to invade or occupy it. With significant exceptions (notably, the Cossacks) the province was predominantly Russian speaking and Russophile.

The coup regime that came to power in Kiev had indicated its intentions to introduce provocative measures hostile to Russian speakers and to pro-Russian sentiment and culture in Ukraine. The Crimean Parliament voted in favor of independence from Ukraine, to whose administration it had been entrusted by Soviet President Nikita Khrushchev in 1954 when both Ukraine and Crimea formed parts of the Soviet Union. Following a public referendum, Crimea then requested that it be annexed to the Russian Federation.

Subsequent reliable opinion polls have indicated continuing popular support for this outcome. In the heavily pro-Russian regions of eastern Donbass, on the other hand, people reacted to the threat of a coup regime in Kiev that was hostile to their interests by establishing the separate republics of Donetsk and Luhansk in April 2014. Neither the republics nor the Russian Federation have shown interest in annexation, although the Russian Federation is a protector of their autonomy within Ukraine but in opposition to the Kiev government.

Two glaring conflicts of national interest

The presumption of Russian guilt in the shooting down of MH17 on July 17, 2014 is extremely convenient to the government of Ukraine. Which is why it is so very problematic that Ukraine, which suffered no loss of life in MH17, has been one of the five nations represented on the Dutch-led JIT while Russia is not a member, and that most of the evidence collected by the JIT has come from Ukrainian intelligence (SBU), a body that exists solely to serve the interests of Ukraine and that has been implicated by MH17 blogger and analyst Hector Reban in theft, torture and murder. Much of the information most sensitive to the case — notably concerning the “Buk route” (the route it is alleged a Buk unit followed to travel from Russia to Donbass and back), intercepted communications, text and visual postings on social media, and the supply of witnesses — comes from the SBU and much of it, by its very nature, is highly susceptible to malpractice or other forms of contamination. The JIT has warmly thanked the SBU for its collaboration and for many months the JIT worked in close proximity to the SBU in Kiev.

It is far from self-evident that Ukraine is not itself a culprit. In the first place, Ukraine failed to shut down the airspace over the combat zone in eastern Donbass for aircraft flying above 30,000 feet, even though many military planes had been shot down, even within hours or days of the MH17 crash, and even though the presence of Ukrainian Buks in at least eight locations in the Donbass, and of Russian Buks in at least three locations in nearby Russia, was a direct threat to civilian airlines flying above 30,000 feet, given the Buk range of 70,000 feet or more. Additionally, there were other Ukrainian air defenses.

Ukrainian Vice Prime Minister Hennadiy Zubko, right, speaks at a briefs journalists on thier investigation into the downing of MH17. Sergei Chuzavkov | AP

Further, there were plausible reasons to suspect that Ukrainian fighters might have been in proximity of MH17, that either they fired on it — for whatever reason — or that they were using the civilian airliner as camouflage to deter enemy ground crews from targeting them with ground-to-air missiles of any kind. Some separatists believe that Kiev kept airspace open precisely because it wanted to retain the option of using civilian airliners for camouflage and because it wanted to provoke an incident of the kind that happened, so as to smear Russia and incite Western intervention. While the likelihood of some of these possibilities has diminished over time (but not completely disappeared), there was far greater uncertainty at the time that the JIT was established in August 2014 (one month after formation of the DSB, which reported 15 months later).

Further, any possible Russian involvement was at best indirect since it stood accused merely of supplying the Buk launcher and missiles used in the attack, not of determining what should be shot down or by whom.

Dutch leadership of the DSB, JIT and subsequent court prosecutions may be justified on the grounds that the Netherlands suffered the largest loss of life (193) of all the countries impacted by MH17. On the other hand, the Netherlands is a highly problematic actor in this context. It is a member of both NATO and the European Union, whose relations with Russia are hostile. The Netherlands was involved in the setting up “civil society” movements in Ukraine in the run-up to the 2014 coup in Kiev. The constitution of the DSB, which investigated the MH17 crash prior to the JIT criminal report, prescribes that it will not report on matters affecting Netherlands security or that prejudice the country’s relations with other states or international organizations, or harm its economic or financial interests. The DSB has a bilateral agreement with its Ukrainian counterpart that includes a non-disclosure agreement.

Dubious forensics

As Eric van de Beek has reported, the defense argued in the pre-trial phase that the crash site was unsupervised for months, so evidence could have been lost, tampered with or planted. Only 30% of the crashed plane, initially, was recovered, and that wreckage could not be collected in a forensically sound fashion. The prosecution was unable to order telephone intercepts on its own authority but was fully dependent on the SBU for this function. The prosecution was unable to carry out network measurements to determine the location of telephones of the accused shortly after the disaster. It was difficult to find witnesses and interview them until many months after the crash.

Soil samples from the alleged launch site could not be taken until long after the event (a year in fact, although some journalists had managed to find the alleged site within days); and the samples were not even investigated, on the grounds that Ukraine had declared that all traces of a Buk launch would have been lost after so long an interval. Motivation for the launch had not been established. No witnesses were interviewed who saw exactly what happened at an altitude of ten kilometers. It was not clear how long Buk missile components had lain at the crash site or how they had arrived there. Autopsies were reportedly performed on 27 bodies,but no reports could be found, or why Ukraine had performed them, or which persons were involved.

Ukrainian Emergency workers carry a body at the crash site of MH17 near the village of Hrabove, eastern Ukraine. Evgeniy Maloletka | AP

Critical to (dis)informational strategies in support of the Dutch-led JIT narrative has been the use of open-source intelligence (OSINT) as a new tool in the armory of propagandists — including, in this instance, the SBU and Bellingcat.com (whose appearance as a ‘citizen journalist’ site debuted two days before the MH17 crash, but is now known to have links with and to be funded by pro-NATO organizations, and to have become a sort of school for spies).

Within hours of the crash, for example, the SBU published wiretaps of separatists discussing a downed plane and images that its agents had “found” on social media (many of them probably originating, according to Reban, from SBU “spotters”), showing the alleged plume of a missile launch and the transport of a Buk ground-to-air missile system. This kind of “evidence” is supremely susceptible to fabrication, manipulation, mistranslation, and misinterpretation in efforts to construct apparently linear narratives from isolated bits of context-free information whose sources are often highly contestable. For example, blogger Van der Werff — who, with Yana Yerlashova of Bonanza Media, produced a critical documentary MH17 – Call for Justice(2019) — spoke to dozens of people in Pervomayskiy, none of whom had seen the plume of smoke in the photo circulated by the SBU.

Bellingcat invested considerable energy in attempts to discredit Ven der Werff, Yerlashova, Bonanza Media (which Bellingcat has claimed to be linked to the GRU), and a local witness, Artyom, who testified against Bellingcat’s preferred narrative of where the missile launch occurred, near the village of Snizhne (see Bonanza Media responses here). Bellingcat claimed that Artyom had retracted his statement, but Artyom denied this in an interview with Yerlashova. Snizhne is preferred by the official account because that account would place it under the control of separatists on the day of the crash, although alternative accounts allege that, in the context of a quickly shifting war drama, the Ukrainian army had wrested temporary control over this area at that time. Opposition narratives, such as that of Russian Buk manufacturer Almaz-Antey, estimate that the launch site was actually Zarosh Henske, 20 kilometers west of Snizhne.

John Helmer, an Australian-born foreign correspondent based in Moscow and a regular commentator on the MH17 case, has identified five methods of witness tampering that had at the very least been discussed in the progression of the official narrative: bribes; offer of early release from prison; threats to kill; covert operations inside Russia, including rendition; and intimidation of relatives. Others have noted that the SBU was the main supplier of witnesses. Some had been arrested by the SBU in investigations into other crimes. Helmer cited Bonanza Media as the source for documentation of a secret conference of JIT-related police and prosecutors at Driebergen in January 2018 (to which Malaysia had not been invited), which discussed approaches to the finding of witnesses. For example, Helmer reported that in focusing on the 53rd Brigade Buk Telar, which they suspected was the source of the missile, participants considered whether to enter Russia secretly to find appropriate witnesses and persuade them to testify to Russian culpability, perhaps bribing or even forcing witnesses out of the country.

One participant was using Russian social media like Vkontakte to reach his Russian targets (a tactic that could incriminate them in the eyes of Russian authorities). There appeared to be consensus that the SBU was well suited to such methods. Writing in March 2020, Helmer claimed that the JIT had not challenged the authenticity of the leaked documents, and that the Australian Federal Police had confirmed them as genuine.

Confirmation bias?

Defense lawyers in the pre-trial phase were concerned, in effect, about a “confirmation bias” that persisted throughout the entire investigation, rooted in initial presumptions of Russian guilt, Russia’s exclusion from the JIT, and the significant and influential presence in the JIT of a party that its critics suspect might itself be culpable: Ukraine. Russia had requested admittance to the JIT in June 2015, arguing that it had noted many times that information and suggestions it had submitted were wrongly interpreted. The JIT had agreed to adopt consensus as its method for making decisions – thus giving Ukraine, the most substantial source of evidence, the power of veto – even though the Dutch retained the final say.

Exemplifying confirmation bias, the defense lawyers who substantiated the preferred “Buk scenario” were often left unchecked, whereas findings that did not fit that scenario were systematically scoured, especially when presented by Russia. And when a Russian source was repudiated (as in the case of the Almaz-Antey report to the Dutch Forensic NFI), there was no further consultation with the source. Even before the wreckage was secure, Ukraine had identified only two types of missile it claimed could be responsible and demonstrated only these two to JIT. The defense was unclear as to why the Ukrainian authorities worked from the Buk scenario from such an early stage of their investigations and why only two missiles (of a much larger potential range) were investigated.

Mikhail Malyshevsky of Almaz-Antei presents evidence at a news conference that MH17 was downed by a model of Buk that is no longer in service with the Russian military but that was part of the Ukrainian military arsenal. Pavel Golovkin | AP

It took Ukraine 18 months to submit logbooks and flight plans that apparently showed that there were no Ukrainian military flights in close proximity to MH17. Yet Ukrainian Sukho Su-25 fighter jets were commonly spotted in eastern Ukraine. The JIT did not investigate the alleged use of civilian flights as human shields. While the prosecution had collected intercepted calls between rebels, it had not collected intercepts between members of the armed forces of Ukraine.

Clearly, Ukraine benefited from the Buk scenario (which allegedly traced the route of a Russian Buk as it traveled from Russia, across the border to Donetsk and onward towards Snizhne and, after the crash, back into Russia). Things that did not support this narrative were not always further investigated or they were explained away, whereas Russian information was examined very carefully and usually discredited. The defense argued that information from Ukraine must be as thoroughly investigated as Russian findings. There remained staggering omissions.

Erik van de Beek saw no evidence that radar or satellite data had been presented to the court in which a Buk or other missile could be spotted. In the pre-trial phase the judge called on the prosecution one more time to request access to U.S. satellite images, but did not call on them to ask Ukraine to deliver military radar data. A former Ukrainian army commander had debunked the claim of the Ministry of Defense that military primary radio stations were not operational on the day of the crash. No intercepted calls convincingly demonstrated the involvement of rebels. (Indeed, on June 26, the prosecution presented an intercept of a conversation between Girkin and Dubinskiy in which Dubinksy told Girkin that a Ukrainian fighter had just downed MH17 and that the rebels had then hit the fighter with a Buk. This had been confirmed by Kharchenko and Pulatov in different conversations.) Eyewitnesses had not come forward to testify against the accused.

These are but a few of the major controversies surrounding the MH17 case. Among other important issues is the shape of metal fragments found in corpses, since this related to which of two possible Buk missile series could have been responsible. This consideration also raised questions about the discovery and handling of bodies and the conduct of autopsies, as well as calculations of missile origin, trajectory and point of impact.

Narrative inconsistencies

Additionally, one might talk of conflicts within the mainstream narrative, discussed by Hector Reban in great detail. For example, there were at least three conflicting hypotheses for the Buk scenario, with some sources claiming that the Buk missile launch trailer traveled with only two vehicles, while others claimed it was part of a much larger armed convoy – the “Vostok convoy” (a difference that had implications for the interpretation of witnesses whose testimony was based on what they heard) — and yet others claimed that the Vostok convoy had been augmented on the route by the Buk launcher. The alleged route, unnecessarily tortuous, has itself invited speculation.

There are several anomalies as to sources of journalistic accounts of sightings of the Buk, and apparent efforts by journalists to remain anonymous. Reban has determined that such journalistic sightings were not direct but based on textual or visual evidence handed to them by anonymous, and possibly intelligence, sources. Other sightings are highly likely to have originated from SBU “spotters” (who were spying on separatist movements, for the benefit of the Interior Ministry and Ukrainian Army), often known to one another, some in direct contact with the Ministry of the Interior and with right-wing affiliates. Images they posted may have been handed to them. Several key images were sent to the JIT without first being posted on social media. Original postings were usually removed within hours, and in some instances the channels on which they were posted were established solely for that purpose before being taken down. There were no pro-separatist sources of such sightings. Only one image was collected of the alleged return of the Buk to Russia.

Most alleged sightings or reports were limited to two critical moments of the Buk route: its crossing of the border and arrival near the launch site. Pre-crash accounts of the Buk presence (i.e., ones that were posted prior to the crash) are meager, and first-hand accounts posted before the crash are non-existent. After the crash, all original images posted on the evening of the 17th were quickly deleted after publication, except for the “launch plume” photo. Some analysts have found it strange that a Buk on a supposedly secretive operation should pass through a highly-populated area in broad daylight, with sirens blaring, its crew sporting suspicious Muscovite accents and dressed in “unfamiliar” gear, while admonishing would-be photographers. This raises suspicion of a false-flag operation and strikes at the very credibility of allegations of a Buk that was shipped from Russia.

A dangerous presumption

Inspection of the MH17 saga teaches us, in the first instance, never simply to presume that an enterprise that appears to have the status of an officially supported and endorsed international legal proceeding must on that account be above reproach. All such institutions are embedded in structures of power in which national interests coalesce and compete in the pursuit of overt and covert agendas, which become ever more complex in situations of war and conflict. In fact to continue with such a procedure may be counter-productive, even from a propaganda point of view, as it may well encounter insurmountable problems of evidence and spur distrust rather than consensus.

Oliver Boyd-Barrett is Professor Emeritus at Bowling Green State University, Ohio and at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. He is an expert on international media, news, and propaganda. His writings can be accessed by subscription at https://oliverboydbarrett.substack.com

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten