A Lesson on Slavery for White America

Paul Street

Contributor

Paul Street holds a doctorate in U.S. history from Binghamton University. He is former vice president for research and planning of the Chicago Urban League. Street is also the author of numerous books,…

Look at the following series of tweets from the president of the United States, reflecting Thursday on the tearing down of Confederate statues in the U.S. South:

Sad to see the history and culture of our great country being ripped apart with the removal of our beautiful statues and monuments. You can’t change history, but you can learn from it. Robert E Lee, Stonewall Jackson—who’s next, Washington, Jefferson? So foolish! Also … the beauty that is being taken out of our cities, towns and parks will be greatly missed and never able to be comparably replaced!

These 69 words are noxious historical nonsense. Of course, we can change history—in the present and the future. The more we know and understand the past, the better we will be situated to alter history in decent and desirable ways.

Which brings us to the Confederacy, whose symbols and statues are now under unprecedented anti-racist scrutiny and have become major white-supremacist rallying points.

The Confederacy: ‘Fighting to Defend the Largest and Most Powerful System of Slavery in the Modern World’

What does it really mean to uphold statues of Confederate military commanders Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee as “beautiful” symbols of the “history and culture of our great country”?

Let there be no mistake. Here is an unchanging fact of history: The Southern Confederacy was formed to preserve, by any means necessary, the vicious, arch-racist, torture and exploitation regime that was black chattel slavery. The Confederacy was a secession government formed by Southern states whose ruling elites had determined that the election of Abraham Lincoln spelled the demise of their beloved slave system. These states openly collaborated to commit treason, taking up arms against “our great country” in order to save slavery.

Roughly 750,000 soldiers died in the Civil War—more than the total killed in all other U.S. wars combined—because of the Southern slave-owning, ruling-class determination to keep 4 million black Americans in chains.

As retired University of Virginia historian Edward Ayers said on “PBS NewsHour” last week, “even if … individual [Confederate] soldiers were not slaveholders, they were fighting to defend a nation that was based on slavery. … The fact is, had they won, you would have had an independent nation overseeing the largest and most powerful system of slavery in the modern world.”

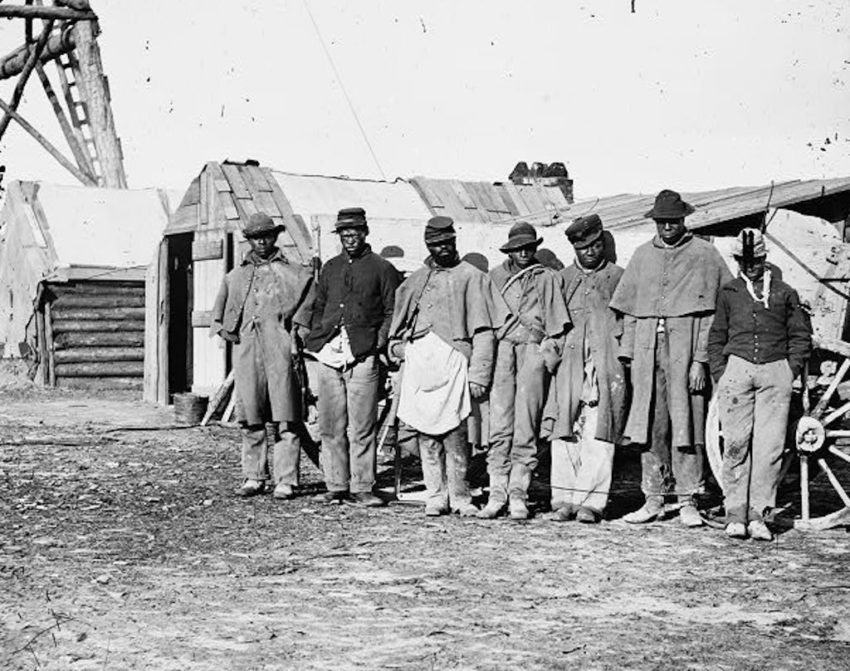

Why on earth couldn’t statues of slave power warlords be more than “comparably replaced” with statues dedicated, say, to the millions of Africans and black Americans killed by the slave system or to the tens of thousands of former slaves who took up arms to join the Union Army in the grand struggle against the slave owners’ criminal Confederacy?

Here, Donald Trump gets an “F” in U.S. history.

The First Secession to Defend Slavery: The American ‘Revolution’

But let us turn to a tougher historical nut—Trump’s claim that going after Jackson and Lee suggests a further turn on statues of the U.S. Founding Fathers George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. This one’s not so simple, I’m afraid. As Trump noted in an impromptu, off-the-rails discussion with reporters last week:

George Washington was a slaveowner [sounds of disapproval in the press corps]. Was George Washington a slaveowner [a reporter says “yes,” and more outrage can be heard]. So, will George Washington now lose his statue? Are we going to take down statues to George Washington? [reporters in a hubbub]. What about Thomas Jefferson? Do you like him? [reporters say “yes,” of course]. OK, good. … He was a major slaveowner. Now, are we going to take down his statue [more clamor can be heard among the journalists]?

Here, Trump gets at least a “B” for historical accuracy—and for the suggestion of moral hypocrisy in the historical sensibilities of his liberal critics. The liberal commentators I’ve seen responding to the president’s Washington and Jefferson comments have all been aghast at Trump’s “slippery slope” suggestion.

They need to take a closer and longer look in the American historical mirror.

Yes, Jefferson and Washington were builders of the early U.S. republic, not advocates of separatist secessions. And yes, Jefferson privately expressed moral and political discomfort with the slave system, whose fruits he enjoyed in more ways than one.

Still, it is unethical folly not to admit that morally consistent opposition to slavery’s symbols should lead us to take down Washington’s and Jefferson’s statues, as well as those of Lee and Jackson. “The Star-Spangled Banner” dripped with the blood of slaves, at least until the Civil War, when historical forces aligned it against the Confederate flag on the battlefields of Antietam, Gettysburg and Vicksburg. As the prolific black historian Gerald Horne showed in his brilliant and provocative 2014 study, “The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America,” the early U.S. republic broke from England in part because its largely slavery-based propertied elite feared that the North American slave regime could not survive and expand under continued rule of the British Empire. The American “Revolution,” Horne shows, was the first American slaveholders’ secession—from the English crown.

The road to independence, Horne shows, was critically paved by two key British actions. In the 1772 Somerset case (Somerset v. Stewart), the British high court ruled that chattel slavery violated English common law. The application of Somerset to the 13 British colonies would have meant an end to the slave machine that fed the coffers of the Yankee mercantile elite and fueled the wealth of New England while it created an opulent landed aristocracy in Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia. The British judge responsible for the decision—William Murray Mansfield—would become a special target of white colonists’ denunciation over the next four years.

A second great British provocation to North American slavery came in 1775, when Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, offered to liberate and arm North American slaves to squash the New England- and New York-based colonial rebellion that had been underway since the Tea Act of 1773. With this action, Dunmore “entered a pre-existing maelstrom of [colonial] insecurity about slavery and London’s intentions,” wrote Horne in “The Counter-Revolution.”

Across the future U.S. South in the spring of 1775, elite colonists were consumed with fears of a slave insurrection allied with the British, Spanish and/or Native Americans. “Lord Dunmore’s proclamation effectively barred any possibility of rebel reconciliation with London,” as the colonists “now confronted Africans armed by London,” explained Horne.

Dunmore’s edict irrevocably joined London with abolition in the minds of the white colonists. It provided a key rallying point for what historian Thelma Wills Foote called “a white settler revolt” and “the white American War for Independence”—fought in no small measure to preserve and expand black chattel slavery. Independence emerged from “the state of the mind of the rebels,” who were already by early 1775 “coming to believe that a London-African combine was mounting against them, leaving secession—a unilateral declaration of independence—as the only way out,” Horne wrote. When Dunmore issued his decree, there was no turning back from white independence, leading Horne to ironically but properly call Lord Dunmore a leading U.S. “Founding Father.”

‘Crimes Which Would Disgrace a Nation of Savages’

It is hardly surprising that North American slaves identified the cause of freedom with London, not the rebels. Tens of thousands of those slaves and a large number of free blacks naturally joined the redcoats. So did many Native Americans, inhabitants of land coveted by the rebellious white colonial setters, who chafed at British restrictions on their territorial expansion.

The colonists’ triumph over London (U.S. independence, attained through the American “Revolutionary” war) “brought about the reassertion of slaveowner control over the enslaved black population in the new republic,” Horne quotes Foote as saying. The North American slave system tightened and expanded across vast swaths of territory stolen from indigenous civilizations in the absence of British restraints. The color line between white and black was drawn with harsher lines than ever before in the “land of liberty.” The white North American settlers’ counter-revolution was a great slavery success—at least until the Civil War, when another white secession and military necessity compelled Lincoln to follow in Lord Dunmore’s footsteps by liberating and arming black slaves.

Jefferson’s heralded Declaration of Independence naturally contained no criticism of North American slavery. It did, however, accuse King George III of “excit[ing] domestic insurrections amongst us.” Another purported sin of the British crown listed in Jefferson’s declaration was that he “endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

This vicious charge against the Native Americans was a total inversion of reality. It was the Euro-American invaders and settlers, not the indigenous inhabitants, who practiced genocide. But the false charge was useful as the young-settler empire geared to ethnically cleanse more First Nations peoples—it’s not for nothing that George Washington was known to the Iroquois as “town destroyer”—to make way for the geographic expansion of its slavery-dependent political economy, which was sanctioned and defended in the Constitution.

Exactly 76 years after U.S. independence was declared and nine years before the Confederate flag was first flown, the great black escaped slave and abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass reflected on “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” According to Douglass, who spoke on a warm summer day in upstate New York as the American flag waved nearby, it was:

[A] day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.

Trump thinks that Jefferson’s and Washington’s statues should stay up, of course, along with Jackson’s and Lee’s.

Cotton Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism

Beyond deleting the great national sin of slavery, Trump made another great historical omission—one he shares with most white Americans, including those who oppose him. I am referring to the need not only to acknowledge the crime of slavery but also to make reparations for its long, crippling impact, whose devastating compound interest legacy still richly fuels the terrible statistics of stark U.S. racial disparity today.

There’s no way to put a precise dollar amount on the value added to American capitalism by the black human beings who provided the critical human raw material for the giant whipping machine that was British North American and U.S. chattel slavery. As historian Edward Baptist has suggested in his brilliant 2014 volume “The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism,” Americans’ tendency to see slavery as a quaint and archaic “pre-modern institution” that had nothing to do with the United States’ rise to wealth and power is deeply mistaken. Contrary to what many abolitionists thought in the 19th century, the savagery and torture perpetrated against slaves in the South was about much more than sadism and psychopathy on the part of slave traders, owners and drivers.

Slavery, Baptist demonstrates, was an incredibly cost-efficient method for extracting surplus value from human beings, far superior in that regard to “free” (wage) labor in the onerous work of planting, tending and harvesting cotton. It was an especially brutal form of capitalism, driven by ruthless yet economically “rational” torture, along with a dehumanizing ideology of racism.

It wasn’t just the South, home to the four wealthiest U.S. states on the eve of the Civil War, where investors profited handsomely from the forced cotton labor of black slaves. By the 1840s, Baptist shows, the “free labor North” had “built a complex industrialized economy on the backs of enslaved people and their highly profitable cotton labor.” Cotton picked by Southern slaves provided the critical cheap raw material for early Northern industrialization and the formation of a new Northern wage-earning populace with money to purchase new and basic commodities.

At the same time, the rapidly expanding slavery frontier provided a major market for early Northern manufactured goods: clothes, hats, cotton collection bags, axes, shoes and much more. Numerous infant industries, technologies and markets spun off from the textile-based Industrial Revolution in the North. Along the way, shipments of cotton to England (the world’s leading industrial power) produced fortunes for Northern merchants, and innovative new financial instruments and methods were developed to provide capital for, and speculate on, the slavery-based cotton boom.

All told, Baptist calculates, by 1836 nearly half the nation’s economic activity derived directly and indirectly from the roughly 1 million black slaves (just 6 percent of the national population) who toiled on the nation’ Southern cotton frontier.

“The Half Has Never Been Told” shows that “the commodification and suffering and forced labor of African-Americans is what made the United States powerful and rich” decades before the Civil War. The U.S. owes much of its wealth and treasure precisely to the super-exploited labor of black chattel slaves in the 19th century. Capitalist cotton slavery was how the United States seized control of the lucrative world market for cotton, the critical raw material for the Industrial Revolution, emerging thereby as a rich and influential nation in the world capitalist system by the second third of the 19th century:

From 1783, at the end of the American Revolution to 1861, the number of slaves in the United States increased five times over, and all this expansion produced a powerful nation … white enslavers were able to force enslaved African American migrants to pick cotton faster and more efficiently than free people. Their practices transformed the southern states into the dominant force in the global cotton market, and cotton was the world’s most widely traded commodity at the time, as it was the key material during the first century of the industrial revolution. The returns from cotton monopoly powered the modernization of the rest of the American economy, and by the time of the Civil War, the United States had become the second nation to undergo large-scale industrialization [emphasis added].

The United States’ later emergence as the world’s leading industrial producer and military superpower is unimaginable without this prior development, rooted in the ruthless capitalist exploitation of black slaves.

Reparations

A critical and underestimated part of the deep societal racism that lives on beneath the “post-racial” American surface—behind the selection of a black Supreme Court justice or the election of a black president or the removal of the Confederate flag or a Confederate war statue in a Southern city—is the steadfast refusal of our longtime white-majority nation to acknowledge that the multi-century history of slavery (the vicious racist and torture system the Confederacy fought to defend and preserve) is intimately related to the nation’s stark racial disparities today.

Forget for a moment that American capitalism is still permeated with institutional, societal and cultural racism. Put aside the basic and important fact that the game is not being played fairly, with genuinely color-blind, “post-racial” rules. Given what is well known about the relationship between historically accumulated resources and current and future success, the very distinction between past and present racism ought to be considered part of the ideological superstructure of contemporary white supremacy.

As anyone who studies capitalism in a smart and honest way knows, what economic actors get from the present and future so-called “free market” is very much about what and how much they bring to that market from the past. And what whites and blacks bring from the living past to the supposedly “color-blind” and “equal opportunity” market of the post-civil rights era (wherein the dominant neoliberal authorities and ideology purport to have gone beyond “considerations of race”) is still shaped by not-so “ancient” decades and centuries of explicit racial oppression.

Even if U.S. capitalism was being conducted without racial discrimination—and vast volumes and data demonstrate that it is not (see my own discussion here—there would still be the question of all the poker chips that white America (superrich, white capitalist America, in particular) has stacked up on its side of the table over centuries of brutal theft from black America. Those surplus chips are not quaintly irrelevant hangovers from “days gone by.” They are living, accumulated weapons of racial inequality in the present and future.

It is long past time for a monumental payback—paid out of giant taxes on the absurdly rich top tenth of the very predominantly white U.S. 1 percent, which owns as much wealth as the bottom U.S. 90 percent.

The class specificity of the payment is critical. We shouldn’t charge lower- and working-class whites a penny for the sins of slavery. American racial oppression, it should always be remembered, has harmed ordinary middle- and working-class white Americans as well as blacks.

From the nation’s colonial origins through the present, the Machiavellian, ruling-class-imposed color line (see Edmund Morgan’s classic 1976 study “American Slavery, American Freedom ” has hurt ordinary whites as well as people of color. Elite-crafted racism has undermined working-class and poor whites’ willingness and ability to join with blacks and other nonwhites in forming the powerful grass-roots alliances and solidarities required to wrest a durably decent living and a democratic society from the wealthy few.

In the place of these basic necessities, the pervasive and living culture of racism—so doggedly persistent that the mild phrase “black lives matter” is somehow controversial more than half a century after the passage of the Civil Rights Act—has offered poor and working-class whites the poisonous, false-compensatory “psychological wage” of whiteness: the belief that while one may occupy a relatively low and insecure position in capitalist America, one was at least more elevated and honored than absurdly demonized nonwhite others.

The always embattled American left has said something else: “Black and White Unite and Fight,” in solidarity against the ruling-class masters. That slogan was no small reflection of how the American industrial workers movement was built in the 1930s and 1940s.

It would be a very good thing for Americans to know more about all this living racial and race-class history—and to know that history can, in fact, be changed, for the better and from the bottom up.