De rel rond de Israëlische spionage-software (spyware) Pegasus breidt zich in razend tempo uit. Donderdag werd bekend dat hooggeplaatste officials van de Palestijnse Autoriteit zijn bespioneerd, onder wie naar verluidt de minister van Buitenlandse Zaken. Op dezelfde dag werd in Mexico een eerste arrestatie verricht nadat de nationale veiligheidsadviseur bleek te zijn afgeluisterd via een Mexicaans bedrijf van een Israëlische zakenman.

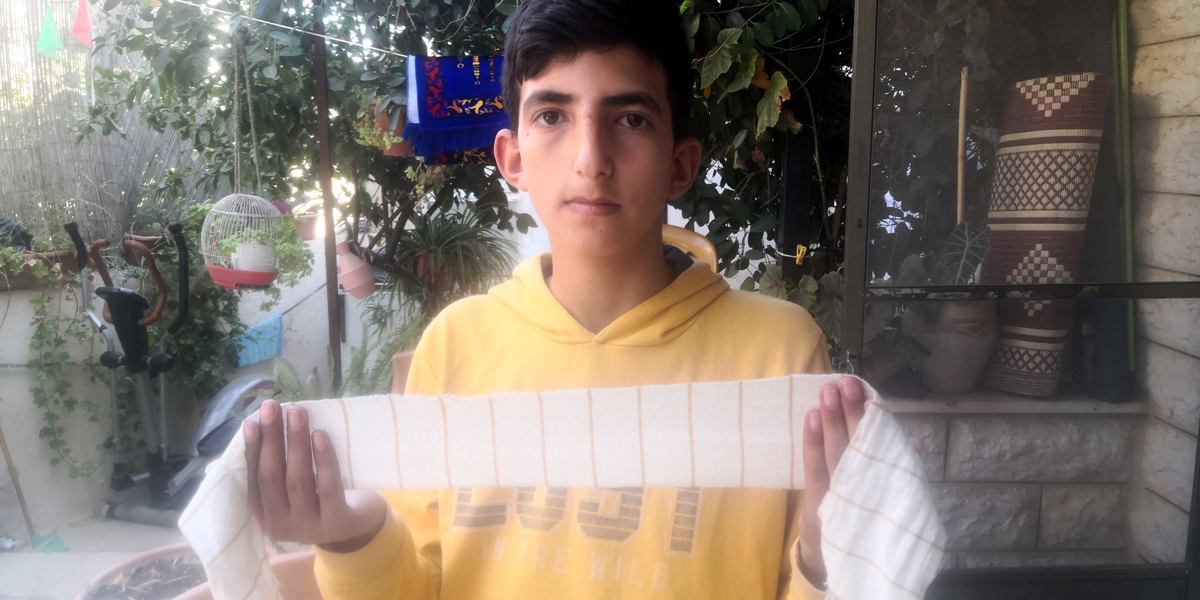

Enkele dagen eerder werd bekend dat spyware was ontdekt op de telefoons van zes Palestijnse mensenrechtenactivisten. Diezelfde dag besloot een Amerikaanse rechtbank dat Facebook een rechtszaak kan aanspannen vanwege het misbruik van zijn WhatsApp-servers. Op 3 november werd de fabrikant van de spyware door de VS op een zwarte lijst geplaatst als risico voor de ‘nationale veiligheid en buitenlandse belangen’. Zwaardere sanctiesdreigen.

Wat is Pegasus?

Diagram van de informatie die via een met Pegasus geïnfecteerde telefoon kan worden verzameld. De gegevens zouden afkomstig zijn uit documentatie van NSO Group, die door WikiLeaks werd geopenbaard. Bron: E-mails van Hacking Team.

Pegasus is spyware die ongemerkt en zonder handeling van het doelwit op iemands telefoon kan worden geïnstalleerd, waarna persoonlijke gegevens en communicatie kunnen worden onderschept. Ook kunnen de microfoon en camera op afstand worden bediend, waardoor toegang wordt verkregen tot de omgeving van het doelwit.

De spyware is ontwikkeld door de Israëlische NSO Group, en mag volgens regelgeving van de Israëlische regering uitsluitend aan overheden worden geleverd (’government exclusive’). Dat proces staat in theorie onder streng toezicht: elke deal vereist een exportlicentie van het Israëlische ministerie van Defensie. Die wordt pas verstrekt nadat het zich heeft verzekerd dat de geleverde spyware uitsluitend wordt gebruikt ter bestrijding van criminaliteit en terrorisme, en niet leidt tot schendingen van de mensenrechten.

‘Hack-for-hire’

Van dat door Israël geschetste beeld van zorgvuldigheid is niets over: tot in het Amerikaanse Congres wordt NSO omschreven als een ‘hack for hire’ voor repressieve regimes, die Pegasus gebruiken om tot ver buiten hun landsgrenzen te spioneren. De spyware blijkt in tenminste 45 landen te worden gebruikt voor het bespioneren van journalisten, mensenrechtenactivisten, ngo’s, vakbondsleiders, politieke dissidenten, advocaten, parlementariërs, ministers en zelfs staatshoofden.

Sinds 2014 ontstond een patroon in de wereldwijd opduikende spionagepraktijken, die werden onderzocht en gedocumenteerd door Amnesty International en het aan de Universiteit van Toronto verbonden Citizen Lab, dat als eerste de technologie ontwikkelde om sporen van Pegasus te kunnen ontdekken op gehackte telefoons.

The Pegasus Project

In 2021 werd de omvang van het Pegasus-schandaal duidelijk toen een lijst met vijftig duizend telefoonnummers van (potentiële) doelwitten in handen kwam van Amnesty International en het Franse journalistieke platform Forbidden Stories. Op de lijst staan zo’n 180 journalisten, maar ook de presidenten van onder meer Frankrijk, Zuid-Afrika en Pakistan, en de voorzitter van de Europese Raad.

Dat leidde tot een grootschalig onderzoek – The Pegasus Project –, waaraan ruim tachtig journalisten van 17 grote media-organisaties meewerkten, ondersteund door Amnesty’s Security Lab dat forensische tests op mobiele telefoons uitvoerde. In juli leidde dat tot een reeks publicaties in internationale media, en een forensisch rapport van Amnesty. Daarnaast creëerde het in Londen gevestigde onderzoeksbureau Forensic Architecture een digitaal platform waarop de verspreiding van Pegasus in kaart wordt gebracht.

In september kwam ook het Europees Parlement in actie tegen het misbruik, en riep de Hoge VN-Commisaris voor de Mensenrechten, Michelle Bachelet, op tot een moratorium op de verkoop van surveillance-technologie. In oktober werd The Pegasus Project door de EU de Daphne Caruana Prize for Journalismtoegekend.

Nederlanders bespioneerd?

Al in 2018 rapporteerde Citizen Lab verdachte infecties met Pegasus-spyware in 45 landen, waaronder Nederland. Daarachter gingen volgens Citizen Lab ten minste 36 ‘operators’ schuil – instrumenten waarmee opdrachtgevers hun spionagepraktijken uitvoeren. In Nederland was een Israëlische operator met de naam DOME actief, evenals in Israël, Palestina, Turkije, Qatar en de VS. Gezien de activiteiten in Israël en Palestina kan DOME alleen opereren in opdracht van Israël en zijn veiligheidsdiensten. Dat roept de vraag op of Israël Nederlanders bespioneert.

Zorgen dat Nederlanders in opdracht van Israël worden bespioneerd, geïntimideerd of zelfs bedreigd bestaan al lang. Eind 2017 beschreven we de strategie en infrastructuur die Israël heeft opgetuigd om organisaties en personen die opkomen voor de rechten van de Palestijnen wereldwijd te bestrijden. Het recent verschenen rapport De ondermijning van pro-Palestijns activisme in Nederland geeft een actueel beeld waartoe die Israëlische strategie in de Nederlandse context heeft geleid.

In Nederland zijn meerdere gevallen bekend van spionage, bedreiging en cyber attacks, waarbij de betrokkenheid van Israël wordt vermoed. In enkele gevallen werd aangifte gedaan, maar onderzoek door het OM en de politie leverde niets op. Onbekend is of telefoons en andere apparatuur zijn onderzocht op sporen van Pegasus, en of de gangen van DOME zijn nagegaan.

Nederlandse kwetsbaarheid

Tegen deze achtergrond bestaan al jaren zorgen over de kwetsbaarheid van Nederland op het gebied van cyber security, waarvoor het Analistennetwerk Nationale Veiligheid in zijn Horizonscan 2018 nadrukkelijk waarschuwde (pagina 23-24):

Op het moment is er op informatietechnologisch gebied een sterke afhankelijkheid van buitenlandse bedrijven. Het overgrote aandeel van de benodigde hard- en software wordt gemaakt in China, de Verenigde Staten en Israël.

De facto zijn Nederland en andere Europese landen dus afhankelijk van deze spelers voor kritieke onderdelen van vitale digitale infrastructuren. Er is hier echter sprake van een zekere naïviteit.

Tot nu toe is het een onderbelicht probleem dat onze samenleving op zeer grote schaal gebruik maakt van buitenlandse apparatuur en technologie, waar mogelijk zogenaamde ‘Back doors’ in zijn gebouwd.

Opmerkelijk is dat de Nationaal Coördinator Terrorismebestrijding en Veiligheid (NCTV) de betrokkenheid van Israël in het op de Horizonscan gebaseerde rapport Cybersecuritybeeld Nederland 2019 wegmoffelde in een voetnoot (pagina 23, noten 83 en 84). Onbekend is of die ingreep getuigt van naïviteit, of een ander doel dient.

Overheid als makelaar

Net zo opmerkelijk was de oproep in april 2020 van de Nederlandse ambassade in Tel Aviv namens het ministerie van VWS aan Nederlandse techbedrijven om samen te werken met een onbekende Israëlische partner aan ‘slimme digitale oplossingen voor corona’. Enkele dagen eerder werd bekenddat NSO westerse regeringen warm probeerde te maken voor zijn corona-software. Het internetmedium Electronic Intifada beschreef de gevaren van een dergelijke ‘corona-samenwerking’.

Alarmerend is de overeenkomst die op 13 oktober jl. tussen Nederland en Israël werd gesloten over uitbouw van de defensiesamenwerking. Daartoe werd een Memorandum of Understanding ondertekend door de Nederlandse ambassadeur in Israël, Hans Docter, en Israëls Defensieminister Benny Gantz. De ambassade in Tel Aviv meldde op Twitter dat die betrekking heeft op ‘security cooperation’ tussen beide landen. Het Haagse ministerie van Defensie beschrijft de deal als ‘defensiesamenwerking’, die ‘vooral [is] gericht op kennisuitwisseling’.

In juli van dit jaar trachtte het ministerie van Economische Zaken Nederlandse bedrijven te koppelen aan de Israëlische wapen- en technologiefabrikant Elbit Systems – paradepaardje van Israëls militaire industrie. Naar verluidt was die poging succesvol.

NSO’s klantenkring

Volgens NSO is Pegasus verkocht aan leger, politie en/of veiligheidsdiensten van veertig landen. Voor die klanten heeft NSO een digitale attack infrastructure opgezet van servers, waarvan de meeste draaien in Europese datacenters van Amerikaanse hosting providers. Vijf servers staan in Nederland.

Met welke landen NSO zaken doet, houdt het geheim. Maar op basis van de gelekte lijst met telefoonnummers werden regeringen van elf landen geïdentificeerd: Azerbeidzjan, Bahrein, Hongarije, India, Kazachstan, Marokko, Mexico, Rwanda, Saudi-Arabië, Togo en de Verenigde Arabische Emiraten (VAE). Die elf spioneerden in tenminste 45 landen.

De overige circa dertig klanten van NSO zijn onbekend, maar steeds duidelijker wordt dat Pegasus niet alleen wordt geleverd aan regeringen of overheidsdiensten, maar ook aan bijvoorbeeld particulieren. Zo kreeg de heerser van Dubai de beschikking over Pegasus om zijn tweede vrouw en haar advocaat te hacken. Schokkend is het laatste nieuws uit Mexico, waar NSO het Mexicaanse bedrijf KBH Track gebruikte om onder meer hoge regeringsfunctionarissen en journalisten af te luisteren.

KBH Track blijkt onderdeel van een conglomeraat van tientallen bedrijfjes in Mexico, de VS en Panama, opgericht door de – inmiddels voortvluchtige – Israëlische zakenman Uri Ansbacher. In Mexico werden 18 van dergelijke bedrijven geïdentificeerd. Volgens de Mexicaanse mensenrechtenorganisatie Article 19 fungeren die als tussenstation tussen NSO en Mexicaanse politie- en veiligheidsdiensten, het leger en het kantoor van de openbaar aanklager.

Vervlochten met de regering

Opmerkelijk zijn de Pegasus-deals die NSO sloot met de VAE (2013) en Bahrein (2017). De in het najaar van 2020 tussen Israël en die landen gesloten Abraham-akkoorden blijken dus een aanloop te hebben gehad. Ook Marokko, dat eind 2020 zijn betrekkingen met Israël normaliseerde, beschikte al jaren over Pegasus. Saudi-Arabië kocht Pegasus in 2017, maar houdt formeel nog afstand van Israël.

In augustus 2020 bevestigde de krant Haaretz dat de Israëlische regering NSO destijds pushte om zijn spyware te verkopen aan de VAE en andere Golfstaten, en weg te kijken bij de slechte reputatie van de regimes. De regering fungeerde zelfs als tussenpersoon, en gaf in strijd met de eigen regels exportlicenties af.

De producten en diensten van NSO en collega-bedrijven als Candiru, Circles, Cellebrite en AnyVision vormen voor de Israëlische regering de ideale entree tot repressieve regimes, terwijl de bedrijven profiteren van een door de regering gecreëerd, exclusief speelveld waarop kapitalen te verdienen zijn. In sommige gevallen werden voor één hack ‘tientallen miljoenen dollars’ betaald.

Hierbij spelen ook persoonlijke belangen een rol. Met name de voormalige premier Netanyahu blijkt Pegasus te hebben ingezet om nieuwe internationale relaties aan te kunnen gaan – om die vervolgens in eigen land politiek te verzilveren. Ook genoemd wordt Yossi Cohen, de voormalige Mossad-chef die het handwerk verrichtte achter de Abraham-akkoorden, maar parallel daaraan werkte aan een particulier investeringsvehikel. Daarbij waren de machthebbers van de VAE, Trumps schoonzoon en adviseur Jared Kushner, en Trumps minister van Financiën Steven Mnuchin betrokken.

Symbiotische relatie

Zowel blogger Richard Silverstein (op Jacobin) als journalist/schrijver Ronen Bergman (in The New York Times) gaan in op de symbiotische relatie tussen de Israëlische regering en de spyware-bedrijven. Silverstein schrijft daarover:

They comprise a network of willing accessories that advance Israeli security interests globally, in addition to their own corporate profits. When the state calls upon them, they offer their services […]. When these cyberwarfare companies face obstacles […], the state comes to their aid.

Bergman – auteur van Rise and Kill First, over de ‘targeted killing programs’ van de Israëlische veiligheidsdiensten – noemt de spyware van NSO een ‘cruciaal element’ in Israëls buitenlandpolitiek:

The company’s biggest backer, the government of Israel, considers the software a crucial element of its foreign policy […].

Dat cruciale belang verklaart ook de Israëlische paniek die volgde op de Amerikaanse sancties tegen NSO Group en Candiru van 3 november. Naar verluidt zijn drie Israëlische ministeries en het kantoor van de premier betrokken bij het uitoefenen van druk op de Amerikaanse regering om de sancties ongedaan te maken. Die inspanning valt slechts te begrijpen vanuit het nationale belang dat voor de Israëli’s op het spel staat.

De kans op Israëlisch succes is klein. Sterker, de kans dat de regering-Biden de sancties verder uitbreidt, en dat die door andere landen worden overgenomen, is aanzienlijk groter. Voor de Amerikanen is de maat vol. Silverstein somt de Israëlische misstappen op:

They’ve sabotaged US telecommunications companies like WhatsApp. In further jeopardizing American interests, Israel has enabled spying on senior US-Iran negotiator Rob Malley. Israel played a key role in the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist. And now they’ve hacked a Palestinian American US citizen.

Gevolgen voor de Palestijnen

In de exportlicenties die het Israëlische ministerie van Defensie aan NSO afgeeft is standaard opgenomen dat de landennummers van Israël en Palestina het exclusieve domein zijn van de Israëlische veiligheidsdiensten, en dus voor elke NSO-klant verboden terrein. De gehackte Palestijnen weten dus met zekerheid dat zij worden bespioneerd door de Israëlische veiligheidsdienst Shin Bet.

Dat is dezelfde organisatie die in mei 2021 trachtte de Nederlandse regering te misleiden met een gefabriceerd dossier over zes Palestijnse ngo’s. Dit in een poging de Nederlandse steun aan drie daarvan te saboteren. Ook dat verhaal krijgt een steeds langer wordende staart. Nadat Nederland en andere Europese landen het Shin Bet-dossier afserveerden, nam Israël zijn toevlucht tot het bespioneren van de ngo’s. Toen dat werd ontdekt, plaatste Israël de zes ngo’s onverwijld op de terreurlijst in een ultieme poging zijn spionagepraktijken te legitimeren. De Palestijnen hebben de VN opgeroepen tot een onderzoek.

Elke Palestijn afgeluisterd

Intussen blijkt de realiteit nog veel grimmiger. Deze week onthulde Middle East Eye dat elke telefoon van Palestijnen op de Westoever en in Gaza kan worden afgeluisterd, dan wel daadwerkelijk wordt afgeluisterd. Daarbij wordt niet alleen gezocht naar eventuele ‘terroristen’, maar worden gewone burgers afgeluisterd op zoek naar compromitterende privé-informatie die hen chantabel maakt. Op elk moment van de dag houden zich hier honderden Israëlische militairen mee bezig.

Vorige week publiceerden wij een artikel over het gezichtsherkenningsprogramma waarmee de Palestijnen dag en nacht gemonitord worden. De digitale controle over de onder bezetting levende Palestijnse bevolking is daarmee totaal. Mag dat? Nee, natuurlijk niet. Maar de rest van de wereld laat het gebeuren. Nu is uitgekomen dat niemand veilig is voor Israëls surveillance-technologie dient dat te veranderen.

https://rightsforum.org/nieuws/bespioneert-israel-nederlandse-ngos-of-burgers-met-pegasus-spyware/?fbclid=IwAR0KgDc8dKE8ndLD1K1dcDJB0oU_009LnXgxnO3pNc7Iv98vwSXqA5MSrgs