zaterdag 6 juli 2024

Biden: 'Ik bestuur de wereld'

Biden: 'Ik bestuur de wereld'

De opmerking van de zittende Amerikaanse president in het interview van vrijdag is door de mainstream genegeerd, maar zijn grootheidswaanzin vormt de kern van de reden waarom Joe Biden zijn partij trotseert en in de race blijft, schrijft Joe Lauria.

By Jo Lauria

Speciaal voor consortiumnieuws

AHalverwege wat werd aangekondigd als het meest consequente interview uit de politieke carrière van Joe Biden, uitte hij de meest consequente woorden in de interview : “Ik bestuur de wereld.”

Deze vijf woorden verklaren waarom hij weigert zich terug te trekken uit de race en bevestigen wat de meeste Amerikanen ontkennen, maar wat het grootste deel van de wereld weet: Amerikaanse presidenten fungeren als wereldkeizers.

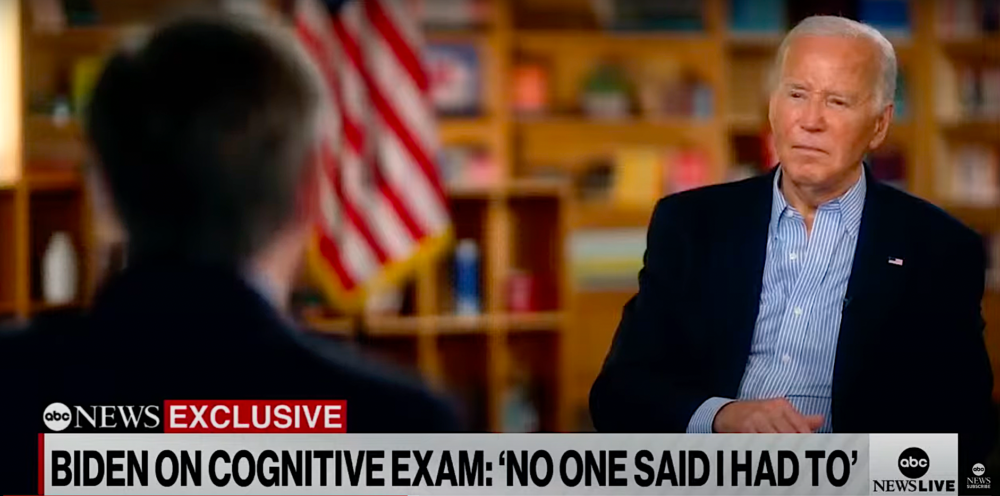

De interview met George Stephanopoulos van ABC News zou Biden's kans zijn om het land te laten zien dat hij mentaal fit is om president te blijven en zich kandidaat te stellen voor een tweede termijn, aan het einde waarvan hij, als hij nog leeft, 86 jaar zou zijn oud.

Biden probeert te herstellen van een debatoptreden op 27 juni, waarin 43.7 miljoen televisiekijkers de verzwakte toestand van zijn geest lieten zien. Over het geheel genomen was hij net zo verward in het debat als hij al jaren is, maar hij heeft nog nooit eerder voor zo'n immens publiek geleefd.

De reactie van de Democratische Partij en haar media was ongekend: experts en redactieleden; Democratische leden van het Congres; partijpolitieke agenten en analisten eisten in schijnbare, gecoördineerde uniformiteit: stop met egoïstisch te zijn Joe en stop met de race, zodat Donald Trump niet wint.

Maar het heeft het tegenovergestelde effect gehad. Biden heeft zich verzet tegen het refrein van de partijelite: ‘Ik ga nergens heen’, zei hij vrijdag tijdens een bijeenkomst. gezegde ten onrechte zou hij Trump in 2020 opnieuw verslaan. Eerder had hij een ontmoeting met gouverneurs van de Democratische staat in het Witte Huis. Hij vertelde hen dat het goed met hem ging. 'Het zijn gewoon mijn hersenen,' zei hij zei, Volgens The New York Times.

En om het publiek te laten zien dat hij nog steeds zijn knikkers heeft, sprak hij met Stephanopoulos in een opgenomen interview, waarvan het onderwerp alleen zijn hersenen betrof.

“GEORGE STEPHANOPOULOS: Zou u bereid zijn een onafhankelijke medische evaluatie te ondergaan die neurologische en cognitief-cognitieve tests omvatte en de resultaten bekend te maken aan het Amerikaanse volk?

PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN: Kijk. Ik heb elke dag een cognitieve test. Elke dag heb ik die test. Alles wat ik doe. Weet je, ik voer niet alleen campagne, maar... Ik bestuur de wereld. Niet – en dat is niet hallo – klinkt als een overdrijving, maar wij zijn de essentiële natie van de wereld.

Madeleine Albright had gelijk. En elke dag bijvoorbeeld, voordat ik hier naar buiten kwam, ben ik aan de telefoon met – met de premier van – nou ja, hoe dan ook, ik zou niet in details moeten treden, maar met Netanyahu. Ik ben aan de telefoon met de nieuwe premier van Engeland.

Ik werk aan wat we in Europa deden met betrekking tot de uitbreiding van de NAVO en of deze stand zal houden. Ik neem het op Poetin. Ik bedoel, er is geen dag dat ik daar doorheen ga, niet de beslissingen die ik elke dag moet nemen.

Biden denkt dat hij de wereld regeert, en dat zal hij niet opgeven. Het maakt niet uit dat hij gek wordt, zodat iedereen het kan zien. Het maakt niet uit dat hij een aanhoudende genocide in Gaza volledig steunt. Het maakt niet uit dat hij uitgelokt en blijft een conflict in Oekraïne uitbreiden dat afstevent op een nucleaire confrontatie met Rusland.

Biden is geobsedeerd door macht – door de macht om ‘de wereld te besturen’. En hij laat niet los.

Amerika is het eerste wereldrijk. De Amerikaanse president is de eerste wereldkeizer. Het debat om het keizerschap te winnen tussen Biden en Trump, het ‘stabiele genie’ dat op zichzelf gestoord was, was een spektakel aan het einde van het imperium, alsof het Caligula was die over Nero debatteerde.

De rest van de wereld huivert van angst over wat hiervan zal komen.

Joe Lauria is hoofdredacteur van Consortium Nieuws en voormalig VN-correspondent voor Thij Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, en andere kranten, waaronder De Montreal Gazette, de Londense Daily Mail en De Ster van Johannesburg. Hij was onderzoeksjournalist voor de Sunday Times uit Londen, een financieel verslaggever voor Bloomberg News en begon zijn professionele werk als 19-jarige stringer voor The New York Times. Hij is de auteur van twee boeken, Een politieke Odyssee, met senator Mike Gravel, voorwoord door Daniel Ellsberg; En Hoe ik verloor van Hillary Clinton, voorwoord door Julian Assange.

Benieuwd hoe haar vader kijkt naar deze beelden van zijn dochter die mooi kwetsbaar haar pijn en angst laat zien. Angst die er al waarschijnlijk al jaren zit, gestoeld op veranderingen in de maatschappij. Andere blikken, andere lichaamstaal, keuzes van de andere rondom jou die je niet kunt plaatsen, denigrerende vragen, plekken waar je je steeds minder welkom voelt, steeds heftigere krantenkoppen, steeds heftigere politiek en niemand die zich er echt om lijkt te bekommeren.

Voor mij staat fier bovenaan de stilte van geliefden, familie, vrienden en kennissen als meest pijnlijke. Kan een Wilders of 100 voor ontbijt hebben, zolang je jezelf niet eenzaam hoeft te voelen staan. Volgens mij was dat ook een van de dingen die Joodse mensen vaak zeiden bij de vraag. Wat was het meest pijnlijke “De stilte van vrienden…”

Dus ieder met moslim vrienden of zij die deze druk ook ervaren door hun identiteit. Wees eens niet zo’n egocentrische, niet inlevende, het komt wel goed betweter en gedraag je menselijk. Dat Rutger Bregman boek in je kast zegt echt 0,0 over je moraal.